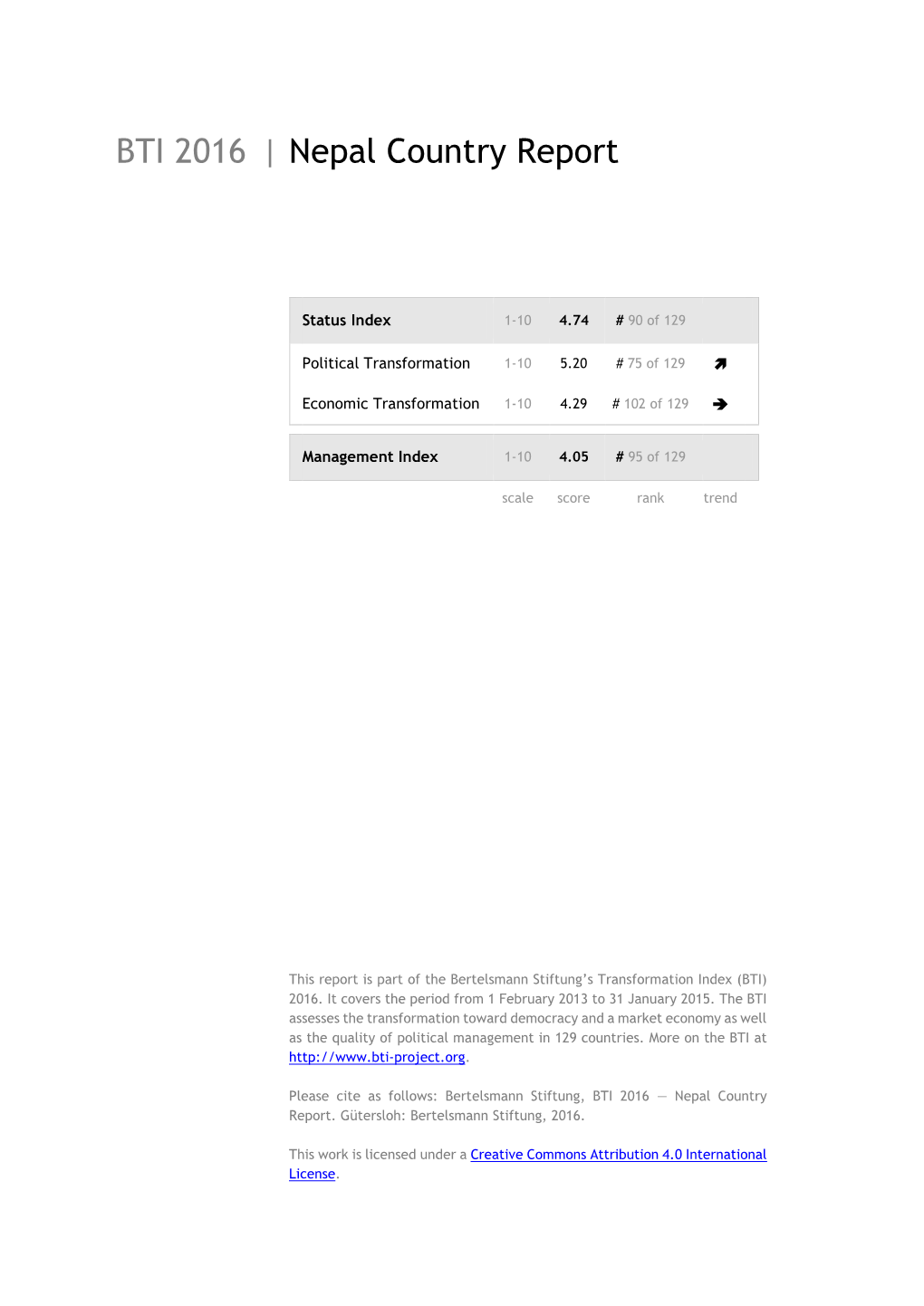

Nepal Country Report BTI 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asian Centre for Human Rights

Asian Centre For Human Rights BRIEFING PAPERS ON NEPAL ISSUE No. 3 Embargoed for : 1 September, 2009 Madhes: The challenges and opportunities for a stable Nepal 1. Introduction dispensation. The Sadbhavana Party continues to occupy one ministerial portfolio. One of the least reported, but most significant changes in Nepali politics since the 2006 People’s Movement is the These three Madhesi parties were critical in helping Madhav emergence of the ‘Madhes’ as a political force. With the Nepal form a majority government. Even now, if two of opening of the democratic space, the Madhesis, who largely these parties withdraw support, the coalition runs the risk but not exclusively live in the southern plains and constitute of losing the confidence vote on the floor of the house.6 33 percent of the population1, asserted themselves. The Madhes speak languages like Maithili, Bhojpuri, Awadhi, All these parties have come together on an anti-Maoist Hindi and Urdu2 and have extensive cross-border ties with plank, sharing the belief that the Maoists must be stopped India3. They challenged the hill-centric notion of Nepali in their quest for ‘total state capture’. They have termed the nationalism and staked claim for greater representation in alliance as a broader democratic alliance. But it is riddled the state structure.4 with internal contradictions. After a period of two and a half volatile years which IN THIS ISSUE has seen the repeated formation and fragmentation 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................... 1 of Madhesi parties, the proliferation of militant armed groups in the Tarai, and reluctant measures by 2. THE ISSUES IN MAHDES ..................................... -

Nepal's Election: a Peaceful Revolution?

NEPAL’S ELECTION: A PEACEFUL REVOLUTION? Asia Report N°155 – 3 July 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE CAMPAIGN ............................................................................................................. 2 A. THE MAOIST MACHINE................................................................................................................2 B. THE STUTTERING CHALLENGE.....................................................................................................3 C. THE MADHESIS PARTIES: MOTIVATION AMID MUTUAL SUSPICION .............................................4 D. THE LEGACY OF CONFLICT ..........................................................................................................5 III. THE VOTE ........................................................................................................................6 A. THE TECHNICAL MANAGEMENT ..................................................................................................6 B. THE VOTE ITSELF ........................................................................................................................7 C. DID VOTERS KNOW WHAT THEY WERE DOING?.........................................................................8 D. REPOLLING ..................................................................................................................................9 -

Nepal-India Think Tank Summit 2018 Opening Ceremony Session I

Summit Schedule Nepal-India Think Tank Summit 2018 Registration and Breakfast 8:00 AM- 9:00 AM 9:00 AM-10:00 AM Opening Ceremony Opening Remarks: Mr. Shyam KC, Research and Development Director, AIDIA Chair Remarks: Shri Shakti Sinha, Director, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) Special Remarks: H.E. Manjeev Singh Puri, Ambassador of India to Nepal Keynote Speech: Shri Ram Madhav, National General Secretary, Bharatiya Janata Party and Director, India Foundation Special Guest Remarks: Hon'ble Mr. Matrika Prasad Yadav, Minister for Industry, Commerce & Supplies Special Address: Chief Guest Rt. Hon’ble Former Prime Minister of Nepal, Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ Vote of Thanks: Mr. Sunil KC, Founder/CEO, Asian Institute and Diplomacy and International Affairs (AIDIA) Opening Session Brief Think Tank, as a shaper of various policy related questions, acts as a bridge between the world of idea and action. And it recommends best possible policy options to the government to meet the daunting challenges in the domestic and the international affairs. The session aims to locate the major role of the think tank in addressing the emerging foreign policy questions and the importance of cooperation between the think-tank of Nepal and India. 10:00 AM-11:30 AM Session I: Building Innovative Cooperation between Indo-Nepal Think Tank: The Partnership Chair Hon'ble Mr. Gagan Thapa, Member of Parliament, Nepali Congress Panelists: Prof. Dr Shambhu Ram Simkhada, Convener, CNI Think Tank, Former Permanent Representative of Nepal to the United Nations Major General Rajiv Narayanan, AVSM, VSM (Retd) Shri Shakti Sinha, Director, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) Dr. -

The Madhesi Movement in Nepal: a Study on Social, Cultural and Political Aspects, 1990- 2015

THE MADHESI MOVEMENT IN NEPAL: A STUDY ON SOCIAL, CULTURAL AND POLITICAL ASPECTS, 1990- 2015 A Dissertation Submitted To Sikkim University In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Philosophy By Anne Mary Gurung DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES February, 2017 DECLARATION I, Anne Mary Gurung, do hereby declare that the subject matter of this dissertation is the record of the work done by me, that the contents of this dissertation did not form the basis of the award of any previous degree to me or to the best of my knowledge to anybody else, and that the dissertation has not been submitted by me for any research degree in any other university/ institute. The dissertation has been checked by using URKUND and has been found within limits as per plagiarism policy and instructions issued from time to time. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science, School of Social Sciences, Sikkim University. Name: Anne Mary Gurung Registration Number: 15/M.Phil/PSC/01 We recommend that this dissertation be placed before the examiners for evaluation. Durga Prasad Chhetri Swastika Pradhan Head of the Department Supervisor CERTIFICATE This to certify that the dissertation entitled, “The Madhesi Movement in Nepal: A Study on Social, Cultural and Political Aspects, 1990-2015” submitted to Sikkim University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Political Science is the result of bonafide research work carried out by Ms. -

Nepal's Future: in Whose Hands?

NEPAL’S FUTURE: IN WHOSE HANDS? Asia Report N°173 – 13 August 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION: THE FRAYING PROCESS ........................................................... 1 II. THE COLLAPSE OF CONSENSUS............................................................................... 2 A. RIDING FOR A FALL......................................................................................................................3 B. OUTFLANKED AND OUTGUNNED..................................................................................................4 C. CONSTITUTIONAL COUP DE GRACE..............................................................................................5 D. ADIEU OR AU REVOIR?................................................................................................................6 III. THE QUESTION OF MAOIST INTENT ...................................................................... 7 A. MAOIST RULE: MORE RAGGED THAN RUTHLESS .........................................................................7 B. THE VIDEO NASTY.......................................................................................................................9 C. THE BEGINNING OF THE END OR THE END OF THE BEGINNING?..................................................11 IV. THE ARMY’S GROWING POLITICAL ROLE ........................................................ 13 A. WAR BY OTHER MEANS.............................................................................................................13 -

International Best Practices Special Docking Nepal's Economic Analysis

NEPAL ECONOMIC FORUM ISSUE 42 | SEPTEMBER 2020 ROAD TO RECOVERY: INTERNATIONAL BEST PRACTICES SPECIAL DOCKING NEPAL'S ECONOMIC ANALYSIS DOCKING NEPAL’S ECONOMIC ANALYSIS ISSUE 42 | SEPTEMBER 2020 CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2020 | ISSUE 42 CONTENTS NEPAL FACTSHEET 4 EDITORIAL 5 1 GENERAL OVERVIEW 7 Political Overview 8 International Economy 11 2 MACROECONOMIC OVERVIEW 16 3 SECTORAL REVIEW 20 Agriculture 21 Energy 23 Infrastructure 25 Real Estate 28 Education 30 Health 33 Tourism 36 Trade and Debt 39 Foreign Aid 43 Remittance 47 Environment 51 4 MARKET REVIEW 53 Financial Market 54 Capital Market 58 5 ROAD TO RECOVERY: INTERNATIONAL BEST PRACTICES SPECIAL 61 6 ENDNOTES 84 7 NEF Profile 90 FACTSHEETNEPAL FACTSHEET KEY ECONOMIC INDICATORS GDP *** USD 29.04 billion GDP Growth rate (%)** 2.3% GNI (PPP) *** USD 3360 Inflation (y-o-y) ** 6.15% Gross Capital Formation (% 50.2% Agriculture sector (% share of GDP)*** 27.65% of GDP) *** HDI * 0.579 Manufacturing sector (% share of GDP)*** 14.27% Rank 147 Service sector (% share of GDP)*** 58.08% *HDI figure from Human Development Report of the UNDP-2019 ** Based on Nepal Rastra Bank's 12 months data of 2019/20 *** Based on World Bank Data EDITORIAL As we head towards Dashain 2020, one cannot help but wonder what the largest festival of Nepal would be like amidst the ongoing pandemic. One Issue 42: September 2020 thing is certain though that this is an unprecedented situation that is going Publisher: Nepal Economic Forum Website: www.nepaleconomicforum.org to last throughout the year. As lockdown has been lifted and restrictions eased, long-distance travel along with domestic flights resumed, and P.O Box 7025, Krishna Galli, Lalitpur — Nepal’s land border opening in a few weeks, movement of people within 3, Nepal the nation, particularly, during the festival period is bound to increase. -

Nepal-Legal Education-Seminar Report-1993-Eng

t n m v s T L a r ? < j_ L eg a l E ducation In N epal Three Day, National Seminar (December 24 - 26,1992) Seminar Proceedings Report Published by : International Commission of Jurists Nepal Section Ramshah Path, P. O. Box : 4659 Kathmandu, Nepal (In Co-operation with International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) / Geneva) International Commission of Jurists Nepal Section Executive Council Mr. Madhu Prasad Sharma Chairman Mr. Moti Kazi Sthapit Vice-chairman Mr. Kusum Shrestha Secretary General Mr. Anup Raj Sharma Treasurer Mr. Krishna Prasad Pant Member Mrs. Silu Singh Member Mr. Daman Dhungana Member Mr. Mahadev Yadav Member Ms. Indira Rana Member M anager Krishna Man Pradhan L e g a l E ducation In N e p a l Three Day National Seminar (December 24 - 26,1992) Seminar Proceedings Report Published by : International Commission of Jurists Nepal Section Ramshah Path, P. O. Box : 4659 Kathmandu, Nepal (In Co-operation with International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) / Geneva) ACKN O WLED G EM ENT This present publication is the outcome of a three day National Seminar on Legal Education In Nepal held on Dec 24-26, 1992 in Kathmandu and organized by ICJ/Nepal Section in collaboration with ICJ/Geneva, Switzerland. I believe the seminar proved to be a successful forum for law teachers, law researchers, lawyers, education planners to come together and discuss issues, problems and priorities in elevating the standards of legal education in the country. Some 245 participants both from the valley and outside representing law campuses, legal profession, judiciary, government agencies contributed meaningfully to the seminar deliberations. -

Nepali Times: on Goit’S Tarai Secession Agenda It Is a Big Problem, but the Cut-Off Date Proposed by TJMM’S Tactics

#310 11 - 17 August 2006 16 pages Rs 30 An unidentified boy plays king at Weekly Internet Poll # 310 traditional Gai Jatra celebrations at Basantapur on Thursday. Q. Rate the performance of the seven party alliance government after 100 days in office.? Tarai Total votes: 4,077 tinderbox Weekly Internet Poll # 311. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com Q. How confident are you about the UN as an effective facilitator for arms management? There’s a brush fire igniting in the tarai, but Kathmandu is too distracted to pay attention SUMAN PRADHAN hile the seven-party government focuses on delicate negotiations with the Maoists, sections of the tarai, where W 48.4 percent of the nation’s population lives, are descending into turmoil. Vigilantism and anti-Maoist activity are turning into sometimes violent ethnically-laced evictions and abductions. Separatist sentiments are getting populist play, while among the intellectual moderate majority there are debates on how the tarai could be best represented in restructuring. Maoists, ex-Maoists, separatists and moderates all see a Nepal polarised between hill and plain. For many Madhesis, anger from long-felt discrimination fuelled by radicalised identity politics is boiling over. Over the past year, Jaya Krishna Goit’s Tarai Janatantrik Mukti Morcha (TJMM), which has been battling Maoists since late 2004, has also been hounding the Pahadiya community, mainly in the central-eastern tarai but also in adjoining areas. Families are rushing to sell off houses and land, and migrate to the hills. Editorial p2 “This trend has picked up recently, Plains speaking many of my friends from Rajbiraj have Nation settled in Kathmandu,” confirms former Slow burn in NC minister Jay Prakash Gupta 'Anand' the tarai p11 who is now general secretary of the Madhesee Janaadhikar Forum (MJM). -

An Application of Doctrine of Necessity: Previous Constituent Assembly of Nepal 117

Jayshwal, An Application of Doctrine of Necessity: Previous Constituent Assembly of Nepal 117 AN APPLICATION OF DOCTRINE OF NECESSITY: PREVIOUS CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF NEPAL AND ITS TIME EXTENSION TO AVOID CONSTITUTIONAL UNCERTAINTY Vijay Pd. Jayshwal* Department of Constitutional Law, Kathmandu School of Law, Dadhikot 09 Purbanchal University-44811, Bhakatpur, New Thimi, Kathmandu, Nepal Abstract This paper aims to investigate issues in relation of constitutional doctrine which had potential debate among the jurists of Nepal for the issues of time extension. The paper will also argue some weaknesses in the constituent assembly and their role expected by the people of Nepal. This paper will discuss about the evolution of constitution in Nepal, its features, the principle of Constitutionalism embodied in Nepalese constitution. This paper will further argue about the legitimacy of Doctrine of Necessity and its application in Nepal. In last, this paper will show the possibility of constitutional uncertainty by newly elected constituent assembly. Keywords: constituent assembly, constitutional uncertainty, constitution. Intisari Penulisan ini dalam rangka mengkaji doktrin konstitusional yang tengah ramai diperdebatkan oleh para ahli hukum di Nepal, khususnya berkaitan dengan isu mengenai perpanjangan waktu. Me- lalui tulisan ini, terdapat temuan yang menunjukkan beberapa kelemahan yang ada dalam majelis konstituate Nepal di samping peran-perannya sebagaimana yang diharapkan oleh rakyat Nepal. Tulisan ini membahas pula mengenai evolusi konstitusi Nepal sebagaimana diwujudkan dalam prinsip-prinsip konstitusionalism yang dianut oleh Konstitusi Nepal. Lebih lanjut, berkaitan de- ngan legitimasi dari Doctrin of Necessity dan penerapannya di Nepal. Pada akhirnya, tulisan ini akan memberikan gambaran mengenai kemungkinan ketidakpastian secara konstitusional berkai- tan dengan kondisi majelis konstituante yang baru saja terpilih. -

Chronology of Major Political Events in Contemporary Nepal

Chronology of major political events in contemporary Nepal 1846–1951 1962 Nepal is ruled by hereditary prime ministers from the Rana clan Mahendra introduces the Partyless Panchayat System under with Shah kings as figureheads. Prime Minister Padma Shamsher a new constitution which places the monarch at the apex of power. promulgates the country’s first constitution, the Government of Nepal The CPN separates into pro-Moscow and pro-Beijing factions, Act, in 1948 but it is never implemented. beginning the pattern of splits and mergers that has continued to the present. 1951 1963 An armed movement led by the Nepali Congress (NC) party, founded in India, ends Rana rule and restores the primacy of the Shah The 1854 Muluki Ain (Law of the Land) is replaced by the new monarchy. King Tribhuvan announces the election to a constituent Muluki Ain. The old Muluki Ain had stratified the society into a rigid assembly and introduces the Interim Government of Nepal Act 1951. caste hierarchy and regulated all social interactions. The most notable feature was in punishment – the lower one’s position in the hierarchy 1951–59 the higher the punishment for the same crime. Governments form and fall as political parties tussle among 1972 themselves and with an increasingly assertive palace. Tribhuvan’s son, Mahendra, ascends to the throne in 1955 and begins Following Mahendra’s death, Birendra becomes king. consolidating power. 1974 1959 A faction of the CPN announces the formation The first parliamentary election is held under the new Constitution of CPN–Fourth Congress. of the Kingdom of Nepal, drafted by the palace. -

Nepali Times

#50 6 - 12 July 2001 20 pages Rs 20 NEPAL’S NICE RICE 10-11 Under My Hat Monsoon survival tips 20 unity of purpose in government or the SUDHIR○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ SHARMA opposition—especially in terms of a joint hen the Communist Party of Nepal strategy on resolving the Maoist issue. (Maoist) held its second convention So, expect the Maoists to continue to w in Dang in February, the party flaunt their presence in Kathmandu, through announced a new Prachanda Path doctrine How many more bodies? booby traps, infiltration of protests against the calling for a “mass uprising” in urban areas to public security regulations, torch take the revolution forward. At the vanguard The Maoist revolution has suddenly moved to fast-forward. processions—especially in the runup to next ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ would be Maoist front organisations of ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Thursday. In the countryside, expect students, women and workers. widespread attacks on police posts. The royal massacre of 1 June prompted The Maoists will also keep taunting the the party to accelerate its preparations for such Army, try to infiltrate its ranks to bring down a mass uprising which would prepare the morale and stoke disunity. In the post- ground for an interim peoples’ government at massacre scenario, the Maoists find themselves the centre. Maoist leaders saw the street propelled to a period they were expecting five protests that followed the massacre and years from now. In a sense it has accelerated widespread public skepticism about the new their revolution, but it also means that they are king as an opportunity to cash in on the not yet prepared to take on the Army. -

Nepal Country Report BTI 2012

BTI 2012 | Nepal Country Report Status Index 1-10 4.45 # 98 of 128 Political Transformation 1-10 5.00 # 74 of 128 Economic Transformation 1-10 3.89 # 112 of 128 Management Index 1-10 3.75 # 101 of 128 scale: 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2012. The BTI is a global assessment of transition processes in which the state of democracy and market economy as well as the quality of political management in 128 transformation and developing countries are evaluated. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2012 — Nepal Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2012. © 2012 Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh BTI 2012 | Nepal 2 Key Indicators Population mn. 30.0 HDI 0.458 GDP p.c. $ 1199 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.8 HDI rank of 187 157 Gini Index 47.3 Life expectancy years 68 UN Education Index 0.356 Poverty3 % 77.6 Urban population % 18.2 Gender inequality2 0.558 Aid per capita $ 29.1 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2011 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2011. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary The high expectations for a new Nepalese political future which followed the 2008 election of a constituent assembly have been cut down by the political reality of power struggle and a policy of blockade. Nepalese politics have since been marked by political turmoil and deadlock.