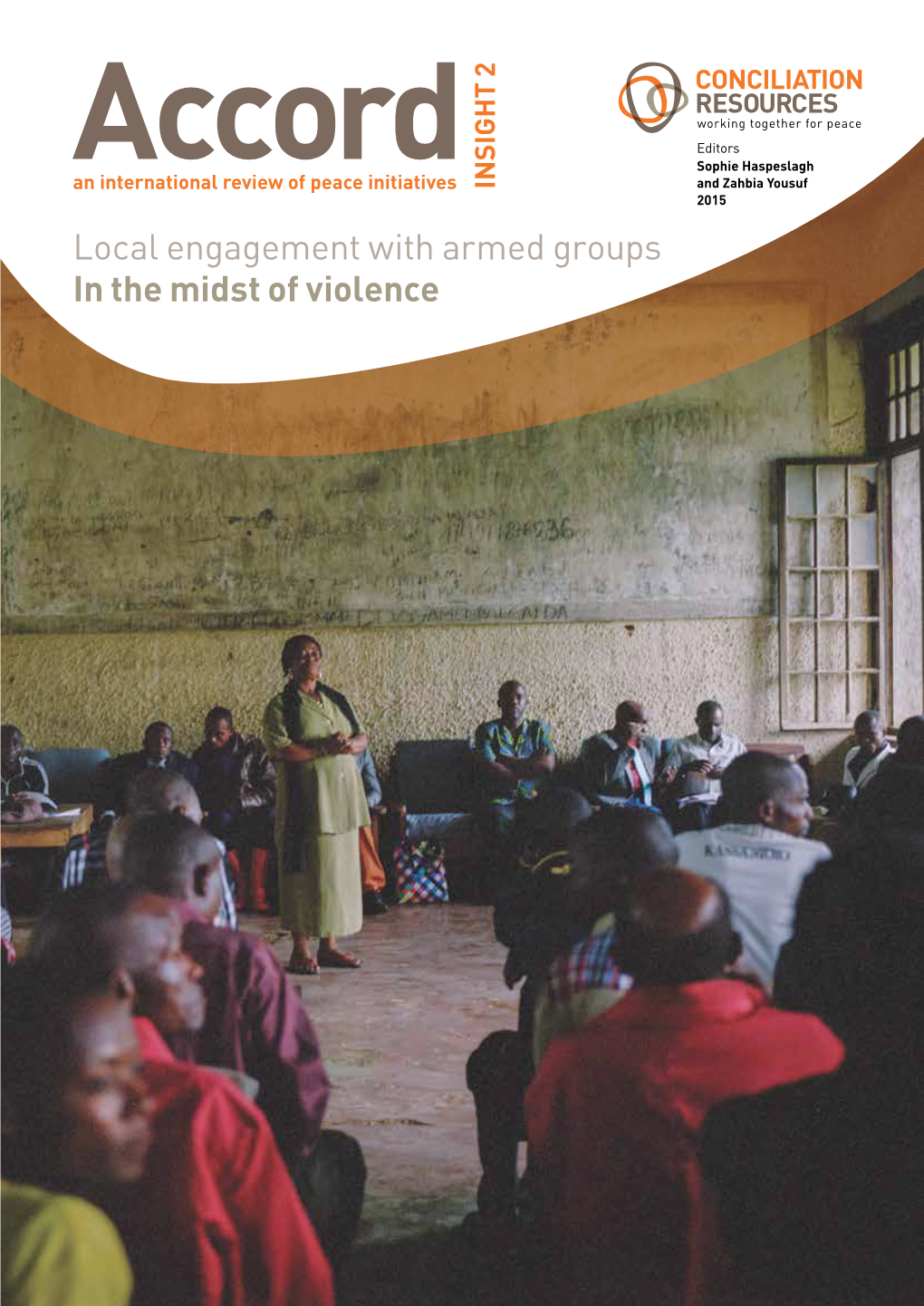

Local Engagement with Armed Groups in the Midst of Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negotiating Peace in Sierra Leone: Confronting the Justice Challenge

Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue rDecembeerp 2007 ort Negotiating peace in Sierra Leone: Confronting the justice challenge Priscilla Hayner Report The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue is an independent and impartial foundation, Contents based in Geneva, that promotes and facilitates 1. Introduction and overview 5 dialogue to resolve armed conflicts and reduce civilian suffering. 2. Background to the 1999 talks 8 114, rue de lausanne 3. Participation in the Lomé talks: April–July 1999 10 ch-1202 geneva 4. Amnesty in the Lomé process and Accord 12 switzerland The context 12 [email protected] t: + 41 22 908 11 30 Rapid agreement on a blanket amnesty 13 f: +41 22 908 11 40 A second look at the amnesty: was it unavoidable? 16 www.hdcentre.org The amnesty and the UN and other international participants 17 © Copyright 5. Other justice issues at Lomé 19 Henry Dunant Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, 2007 A Truth and Reconciliation Commission 19 Reproduction of all or Provisions for reparations 20 part of this publication The security forces and demobilisation of combatants 20 may be authorised only Reaching an agreement on power-sharing 21 with written consent and acknowledgement of the 6. After the agreement: a difficult peace 22 source. Slow implementation and near collapse of the accord 23 The International Center The Special Court for Sierra Leone 25 for Transitional Justice Implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission 26 assists countries pursuing Judicial reform efforts 28 accountability for past mass Creation of a new Human Rights Commission 28 atrocity or human rights abuse. It assists in the development Demobilisation, and reform of the armed forces and police 29 of integrated, comprehensive, and localized approaches to 7. -

Conflict Analysis of Liberia

Conflict analysis of Liberia February 2014 Siân Herbert About this report This rapid review provides a short synthesis of the literature on conflict and peace in Liberia. It aims to orient policymakers to the key debates and emerging issues. It was prepared for the European Commission’s Instrument for Stability, © European Union 2014. The views expressed in this report are those of the author, and do not represent the opinions or views of the European Union, the GSDRC, or the partner agencies of the GSDRC. The author extends thanks to Dr Mats Utas (The Nordic Africa Institute), who acted as consultant and peer reviewer for this report. Expert contributors Dr Thomas Jaye (Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre) Diego Osorio (former United Nations Mission in Liberia) Dr Sukanya Podder (Cranfield University) Dr Alexander Ramsbotham (Conciliation Resources) Eric Werker (Harvard Business School) Craig Lamberton (USAID) Julia Escalona (USAID) Tiana Martin (USAID) Suggested citation Herbert, S. (2014). Conflict analysis of Liberia. Birmingham, UK: GSDRC, University of Birmingham. About GSDRC GSDRC is a partnership of research institutes, think-tanks and consultancy organisations with expertise in governance, social development, humanitarian and conflict issues. We provide applied knowledge services on demand and online. Our specialist research team supports a range of international development agencies, synthesising the latest evidence and expert thinking to inform policy and practice. GSDRC, International Development Department, College of Social Sciences University of Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK www.gsdrc.org [email protected] Conflict analysis of Liberia Contents 1. Overview 1 2. Conflict and violence profile 2 3. Principal domestic actors 4 3.1 Political personalities and parties 3.2 Principal security actors 3.3 Ex-combatants and ex-commanders 3.4 Civil society organisations 4. -

Paix Sans Frontières Building Peace Across Borders

ISSUE ISSUE 22 Accord 22 Accord edited by an international review of peace initiatives Alexander Ramsbotham Paix sans frontières and I William Zartman 2011 building peace across borders ISSUE Paix sans frontières Armed confl ict does not respect political or territorial 22 22 boundaries. It forms part of wider, regional confl ict systems. building peace But there is a policy gap across borders and in borderlands 2011 where statehood and diplomacy can struggle to reach, across borders as confl ict response strategies still focus on the nation state as the central unit of analysis and intervention. This twenty-second publication in Conciliation Resources’ Accord series addresses this gap. It looks at how peacebuilding strategies and capacity can ‘think outside the state’: beyond the state, through regional engagement, and below it, through cross-border community or trade networks. building peace across borders across peace building “In many of today’s wars, violence is driven in part by cross- border regional confl ict dynamics. And, as this important new publication from Conciliation Resources makes clear, failure to take the regional dimension of civil wars into account increases the risk that peacebuilding strategies will fail. What is needed, in addition to the statebuilding policies that are now de rigeur in post-confl ict environments, are strategies that address cross- border confl ict dynamics with the relevant regional states and cross-border communal engagement.” Andrew Mack, Director of the Human Security Report Project (HSRP) at Simon Fraser University and a faculty member of the university’s School for International Studies. Conciliation Resources is an international non-governmental organisation that works in fragile and confl ict-affected states to prevent violence, promote justice and transform confl ict into opportunities for development. -

Designing a Comprehensive Peace Process for Afghanistan

[PEACEW RKS [ DESIGNING A COMPREHENSIVE PEACE PROCESS FOR AFGHANISTAN Lisa Schirch, with contributions from Aziz Rafiee,N ilofar Sakhi, and Mirwais Wardak PW75_Cover_3a.indd 1 9/13/11 10:27:11 AM [PEACEW RKS [ ABOUT THE REPO R T This report, sponsored by the Center for Conflict Management at the U.S. Institute of Peace, draws on comparative research literature on peace processes to identify lessons applicable to Afghanistan and makes recommendations to the international community, the Afghan government, and Afghan civil society for ensuring a more comprehensive, successful, and sustainable peace process. Research for this paper was undertaken during five trips to Kabul, Afghanistan, and one trip to Pakistan between 2009 and 2011. Funding for the research in the report came from the Ploughshares Fund and Afghanistan: Pathways to Peace, a project of Peacebuild: The Canadian Peacebuilding Network. ABOUT THE AUTHO R Lisa Schirch is director of 3P Human Security, a partnership for peacebuilding policy. 3P Human Security connects policymakers with global civil society networks, facilitates civil-military dialogue, and provides a peacebuilding lens on current policy issues. She is also a research professor at the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding at Eastern Mennonite University and a policy adviser for the Alliance for Peacebuilding. A former Fulbright Fellow in East and West Africa, Schirch has worked in more than twenty countries in conflict prevention and peacebuilding. Schirch has written four books and numerous articles on conflict prevention and strategic peacebuilding. Photo taken by members of Peace Studies Network of Department of Peace Studies (NCPR) from Psychology and Educational Sciences Faculty of Kabul University in 2009. -

Dialogue for Peace Reflections and Lessons from Community Peace Platforms in the Mano River Region

Fall 08 Discussion paper Nov 2016 Dialogue for Peace Reflections and lessons from community peace platforms in the Mano River region NGO partners This project has been implemented in partnership with the following national NGOs: ABC Development is a registered NGO in Guinea, established in 1998. It is a member of the West Africa Action on Small Arms and WANEP in Guinea. In partnership with Conciliation Resources, ABC Development set up the DPD in Forécariah, which has led dialogue between mining companies and communities in the surrounding region. Institute for Research and Democratic Development (IREDD) was founded in Liberia in 2000 (as the Liberia Democratic Institute) and serves on several civil society networks in Liberia that engage in policy influencing. It works to strengthen citizens’ voices and engender a culture of local participation in policy development and implementation. Network Movement for Justice and Development (NMJD) in Sierra Leone is an advocacy and peacebuilding national civil society organisation, established in 1988. It has a wide range of experiences working in partnership with national and international institutions to build capacities, create and influence policies on mining, governance, peace and security and youth empowerment. West Africa Network for Peacebuilding–Côte d’Ivoire (WANEP-CI) is the Ivorian branch of WANEP, a leading regional peacebuilding organisation founded in 1998 operating in every ECOWAS member state. WANEP is experienced in bringing people together through dialogue platforms to promote -

Inclusion of Gender and Sexual Minorities in Peacebuilding

Report July 2018 Inclusion of gender and sexual minorities in peacebuilding Background What are the barriers to and benefts of meaningful participation of gender and Methodology sexual minorities in peace processes and Case study participants were identifed how can their participation be supported? through a combination of Conciliation What can their experience tell us more Resources’ staff and partner organisations broadly about inclusion in peace processes? in the two contexts. Semi-structured interviews took place over video call and by Conciliation Resources is an international email with two activists, one a member of a peacebuilding organisation with a strong focus non-governmental organisation. Participants’ on supporting inclusive peace processes. We permission was sought and granted as to have learnt that gender, a key aspect of inclusion, the purpose of the research, how it would be continues to be misunderstood and overlooKed. shared and the identifcation of interviewees. Each interview explored the same core MeaningFul participation of women and other questions, with follow-up discussions where excluded groups in peace processes is important necessary. The research examined how For sustainable peace, yet to date has been the participants bring the voices of gender limited and lacKing in diversity. Women and other and sexual minority people and groups into excluded groups experience multiple forms of peace processes or other political processes; discrimination related to their diverse gender how this work benefts peace processes; identities. These exacerbate social, legal, economic, challenges they have experienced; and cultural, as well as political marginalisation; and the role of international organisations in violent conFlict compounds discrimination.1 supporting this work. -

Conciliation Resources

conciliation resources Strategic Plan 2009-2011 Preparing the Ground for Peace Contents Global context 3 Key challenges for Conciliation Resources 4 About Conciliation Resources as an organization 5 Our vision 5 Our Mission 5 Our approach 5 The shared understanding that guides our work 6 Making strategic choices for the next three years (2009-2011) 7 The strategic planning process 7 Purpose of this plan 7 Resourcing implications 7 Putting the strategy into practice 8 Performance management implications 8 Structure of the objectives diagram 8 Our Three-year Strategy 9 2 Conciliation Resources Students debating at CRÕs Security Analysis School, Sierra Leone. © Rosalind Hanson-Alp/ Conciliation Resources Global context We live in a world of conflicts, heavily and international governance systems are failing to offer effective responses for prevention and resolution. The armed and unequally violent. Where human and institutional resources as well as the necessary you are born strongly influences your political commitment to prevent, resolve and transform opportunities and vulnerabilities. conflicts are in short supply in stark contrast to government investments in military security. There are at least 60 ongoing conflicts globally with The good news is that the number of armed conflicts is 28 suffering an intensity of violence of 100 or more battle- reportedly in decline, and while civilian deaths continue related deaths. In Iraq there have been an estimated one to be proportionally higher than combatant deaths in most million civilian casualties since 2003. More staggering, contemporary conflicts, total war deaths are lower than there have been an estimated 5.4 million deaths in the ever before. -

Legitimacy and Peace Processes from Coercion to Consent ISSUE 25 Accord 25 ISSUE an International Review of Peace Initiatives

Accord Logo using multiply on 25 layers 2014 Accord ISSUE Logo drawn as Editors seperate elements with overlaps an international review of peace initiatives coloured seperately Alexander Ramsbotham and Achim Wennmann 2014 Legitimacy and peace processes From coercion to consent Legitimacy and peace processes From coercion to consent ISSUE 25 25 Accord ISSUE an international review of peace initiatives Legitimacy and peace processes From coercion to consent April 2014 // Editors Alexander Ramsbotham and Achim Wennmann Accord // ISSUE 25 // www.c-r.org Published by Conciliation Resources, to inform and strengthen peace processes worldwide by documenting and analysing the lessons of peacebuilding Published by Acknowledgements Conciliation Resources Accord’s strength and value relies on the Burghley Yard, 106 Burghley Road expertise, experience and perspectives of the London, NW5 1AL range people who contribute to Accord projects www.c-r.org in a variety of ways. We would like to give special thanks to: Aden Telephone +44 (0)207 359 7728 Abdi, Ali Chahine, Catherine Barnes, Ciaran Fax +44 (0)207 359 4081 O’Toole, Ed Garcia, Elizabeth Picard, Judith Email [email protected] Large, Lisa Schirch, Nerea Bilbatua and Teresa Whitfield. UK charity registration number 1055436 In addition to all our authors, we also extend grateful thanks to the many other expert Editors contributors to this Accord publication: Alexander Ramsbotham and Achim Wennmann Abdulrazag Elaradi, Andrew Tomlinson, Antonia Executive Director Does, Asanga Welikala, Babu Rahman, Catherine -

The Karabakh Trap Dangers and Dilemmas of the Nagorny Karabakh Conflict1

conciliation resources The Karabakh trap Dangers and dilemmas of the Nagorny Karabakh conflict1 By Thomas de Waal 2 Introduction The unresolved Armenian-Azerbaijani dispute over Nagorny Karabakh (NK) still looms threateningly over the South Caucasus, but is low down the international agenda. NK is generally termed a “frozen conflict,” but the term is misleading and potentially dangerous; in fact the dispute is in a state of dynamic change that could eventually lead to the resumption of fighting. The facts on the ground are changing while the opposing repeated the message that a victory has been won and it sides, isolated from each other for two decades now, have only remains for Azerbaijan and the world to accept this. a poor grasp of what the other is thinking. As the situation Armenian minister of defence Seiran Ohanian (himself a changes, the danger in particular of a breakdown of the Karabakhi) said on July 29 2008, “Azerbaijan went down self-regulating ceasefire on the Line of Contact (LOC) the military path in resolving the conflict. The Nagorny between the two armies is especially worrying. Karabakh issue has already been resolved by force [in the Armenians’ favour], now we need to bring the issue to a This paper is an analysis of how the facts of the conflict logical resolution by diplomatic means.” are changing, of why the peace process is failing to move forward and the dangers that lie ahead over the next five NK is perceived by Armenians as a purely Armenian to ten years. It is aimed at stimulating a debate about the territory liberated from Azerbaijan. -

Consolidating Peace Liberia and Sierra Leone Consolidating Peace: Liberia and Sierra Leone Issue 23 Accord 23 Issue an International Review of Peace Initiatives

Accord Logo using multiply on layers 23 issue issue Logo drawn as Issue editors seperate elements Accord with overlaps an international review of peace initiatives coloured seperately Elizabeth Drew and Alexander Ramsbotham 2012 Consolidating peace Liberia and Sierra Leone Consolidating peace: Consolidating peace: Liberia and Sierra Leone Liberia and Sierra issue issue 23 23 Accord issue an international review of peace initiatives Consolidating peace Liberia and sierra Leone March 2012 // Issue editors Elizabeth Drew and Alexander Ramsbotham Accord // Issue 23 // www.c-r.org Published by Conciliation Resources, to inform and strengthen peace processes worldwide by documenting and analysing the lessons of peacebuilding Published by Acknowledgements Conciliation Resources Conciliation Resources would like to give 173 Upper Street, London N1 1RG special thanks for editorial and project advice and assistance provided by Carolyn Norris and www.c-r.org Sofia Goinhas. Telephone +44 (0) 207 359 7728 In addition we extend grateful thanks to our Fax +44 (0) 207 359 4081 authors, peer reviewers, photographers and Email [email protected] all those who have contributed to the conception UK charity registration number 1055436 and production of this publication: Eldridge Adolfo, Harold Aidoo, Ecoma Alaga, Editors Natalie Ashworth, Conrad Bailey, Catherine Elizabeth Drew and Alexander Ramsbotham Barley, Abu Brima, Rachel Cooper, Lisa Denney, Executive Director Said Djinnit, Sam Gbaydee Doe, Rasheed Draman, Andy Carl Comfort Ero, Richard Fanthorpe, Lans -

Ismail ST Tarawali, Freetown, Sierra Leone

TAK ING ASTAND AGAINST WAR. OUR WORK IN REVIEW Our vision is a world where people affected by conflict and their leaders are able to work effectively with international suppo rt to prevent violence, resolve their armed conflicts and build more peaceful societies. Conciliation Resources is an international non-governmental organization Contents with over 15 years of experience working internationally to prevent and Choosing the path to peaceful political settlements 4 – 7 resolve violent conflict. Our practical and policy work is informed by people living in countries affected by or threatened by war. Interviews with our partners 8 – 17 Last year we supported partners in the Caucasus, Central African Where we work 18 – 19 Republic, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Fiji, Guinea, Highlights of our work 20 – 29 India, Liberia, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan • Supporting people to develop effective solutions 20 – 21 and Uganda. We also publish Accord: an international review of peace • Challenging stereotypes and increasing public awareness 22 – 23 initiatives and seek to influence government peacemaking policies. Our • Providing opportunities for dialogue 24 – 25 funding is mainly through grants from governments, multilateral • Improving peacemaking practice and policy 26 – 27 agencies, independent trusts and foundations. • Influencing governments and other decision makers 28 – 29 Conciliation Resources is registered as a charity in the UK. Finance and accounts 30 – 33 Charity Number 1055436. Board, staff and associates 34 – 35 2 www.c-r.org conciliation resources work in review 3 CHOOSING THE PEACEFUL PATH TO POLITICAL SETTLEMENTS Conciliation Resources is privileged to work directly with This question guides our work. -

Appointment Brief – Chair of Trustees

April 2018 Appointment Brief – Chair Of Trustees Logo using multiply on layers Logo drawn as seperate elements with overlaps coloured seperately Appointment Brief – Chair Of Trustees Introduction, from Jonathan Cohen OBE, Nigeria), Papua New Guinea / Bougainville Executive Director and the Philippines. Key themes that underpin our work are: engaging armed groups; peace processes, dialogue and mediation support; public participation; gender and peacebuilding; and political settlements. We are looking for a Chair who embodies the organisation’s values of collaboration, creativity, challenge and commitment. We are seeking a new Chair to provide leadership and direction to our Board of Trustees so that it can fulfil its responsibilities for the overall governance and strategic direction of the charity. You will have At Conciliation Resources, we are immensely the opportunity to work with a passionate Board proud of our impact in preventing violent conflict of Trustees, an outstanding executive team and a and achieving lasting peace. As a leading dynamic staff collective. peacebuilding charity, we are committed to Whether from the private, public or non-profit finding an outstanding individual to lead our sector, our ideal candidate will display keen Board of Trustees through our next phase of judgement and bring experience of senior development. The current Chair, Rt Revd Peter leadership and provide motivating support Price, having come to the role from the House of and challenge to colleagues. You should Lords and a career in peacebuilding, is stepping have previous board experience and a clear down after five years in the role. This period understanding of good governance. In addition, has seen the organisation grow and develop the you should have strong networking skills and quality of its work.