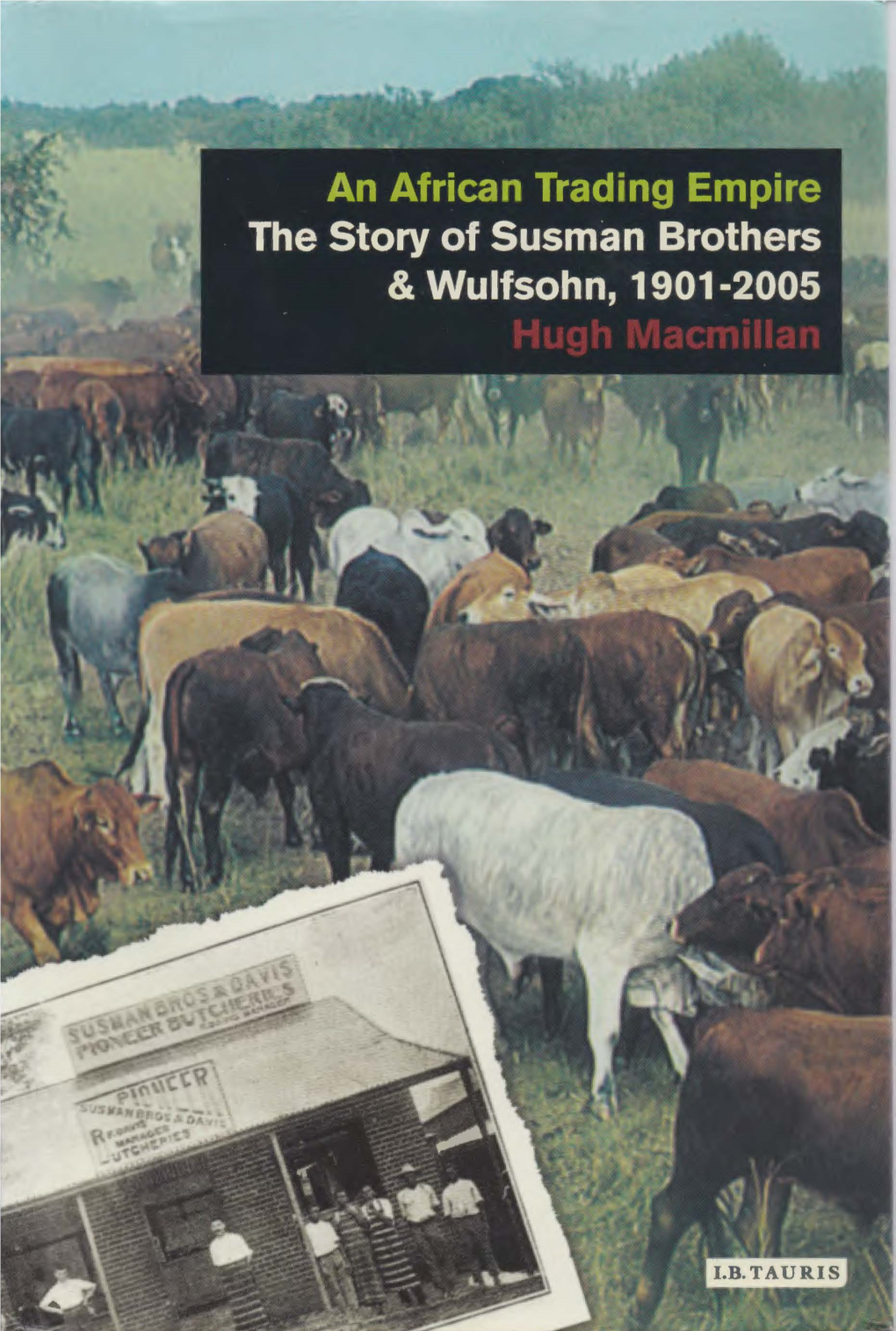

African Trading Empire WMM 1885-1974 MCMM 1908-2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and References

Notes and References 1 The Foundation of Kenya Colony I. P[ublic] R[ecord] O[ffice] Kew CO 533/234 ff 432-44. Kenya was how Johann Krapf, the German missionary who was in 1849 the first white man to see the mountain, transliterated the Kamba pronunciation of the Kikuyu name for it, Kirinyaga. The Kamba substituted glottal stops for intermediate consonants, hence 'Ki-i-ny-a'. T. C. Colchester, 'Origins of Kenya as the Name of the Country', Rhodes House. Mss Afr s.1849. 2. PRO CO 822/3117 Malcolm MacDonald to Duncan Sandys. Secret and Personal. 18 September 1963. 3. The new rail routes in question were the Uasin Gishu line and the Thika extension. M. F. Hill, Permanent Way. The StOlY of the Kenya and Uganda Railway (Nairobi: East African Railways and Harbours, 2nd edn 1961), p. 392. 4. Daily Sketch, 5 July 1920, p. 5. 5. Sekallyolya ('the crane [or stork] looking out on the world') was first printed in Nairobi in the Luganda language in 1921. From time to time it brought out editions in Swahili and for special occasions in English. Harry Thuku's Tangazo was the first Kenya African single sheet newsletter. 6. Interview with James Beauttah, Fort Hall, 1964. Beauttah was one of the first English-speaking African telephone operators. He claimed to be the first African to have electricity in his house. 7. PRO FO 2/377 A. Gray to FO, 16 February 1900, 'Memo on Report of Law Officers of the Crown reo East Africa and Uganda Protector ates'. The effect of the opinion of the law officers is that Her Majesty has, by virtue of her Protectorate, entire control over all lands unappropriated .. -

The Colonial Government and the Great Depression in Northern

THE COLONIAL GOVERNMENT AND THE GREAT DEPRESSION IN NORTHERN RHODESIA: ADMINISTRATIVE AND LEGISLATIVE CHANGES, 1929-1939 BY MBOZI SANTEBE A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Zambia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History THE UNIVERSITY OF ZAMBIA LUSAKA © 2015 i DECLARATION I, Mbozi Santebe, declare that this dissertation (a) Represents my own work; (b) Has not previously been submitted for a degree at this or any other University; and (c) Does not incorporate any published work or material from another dissertation. Signed …………………………………………………………………………………….. Date ……………………………………………………………………………………... ii COPYRIGHT All rights reserved. No part of this dissertation may be reproduced or stored in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the author or the University of Zambia. iii APPROVAL This dissertation of Mbozi Santebe is approved as fulfilling the partial requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in History by the University of Zambia. Date Signed ………………………………………………. …………………………….. Signed ………………………………………………. …………………………….. Signed ………………………………………………. …………………………….. iv ABSTRACT This study focuses on the administrative and legislative changes that the colonial government made in response to the impact of the Great Depression in Northern Rhodesia. It reveals that the government mainly responded to the decline in government revenues, the widespread poverty and destitution and the distortion of internal trade. The study shows that during the emergency period, 1932-1934, the administration made changes to government structures and functioning so as to curtail expenditure and balance its budget. It reorganised staff in the public service, reduced budgetary allocations to departments and realigned several departments and provinces. -

Climate Change Impacts, Vulnerability, and Adaptation Options Among the Lozi Speaking People in the Barotse Floodplain of Zambia

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 6, Issue 9, September 2019, PP 149-157 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0609017 www.arcjournals.org Climate Change Impacts, Vulnerability, and Adaptation Options among the Lozi Speaking People in the Barotse Floodplain of Zambia Milupi, I. D1*, Njungu, M 2, Moonga, S. M.1, Namafe, C. M.1, Monde, P. N1, Simooya, S. M1 1The University of Zambia, School of Education, Department of Language and Social Sciences Education. P.O BOX 32379, Lusaka, Zambia 2University of Waterloo, School of Public Health and Health Systems, LHN 2717,200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, Canada *Corresponding Author: Milupi, I. D, The University of Zambia, School of Education, Department of Language and Social Sciences Education. P.O BOX 32379, Lusaka, Zambia Abstract: The aims of this study were: - to find out how communities in the Barotse floodplain of Mongu district in Zambia are affected by climate change, establish adaptation opportunities practiced by the Lozi people and to raise awareness and stimulate interest in matters of climate change. Using primary and secondary data sources, it was observed that the negative impacts of climate change among the Lozi people include; increase in atmospheric pressure and excessive heat and flooding, prolonged spells of unexpected changes in seasons, reduction in food production and security, as well as inadequate clean water supply and extinction of some plant and animal species. The study also revealed vast local ecological knowledge that, if utilised, may help in the adaptation of climate change. -

Encounters Between Jesuit and Protestant Missionaries in Their Approaches to Evangelization in Zambia

chapter 4 Encounters between Jesuit and Protestant Missionaries in their Approaches to Evangelization in Zambia Choobe Maambo, s.j. Africa’s reception of Christianity and the pace at which the faith permeated the continent were incredibly slow. Although the north, especially Ethiopia and Egypt, is believed to have come under Christian influence as early as the first century, it was not until the fourth century that Christianity became more widespread in north Africa under the influence of the patristic fathers. From the time of the African church fathers up until the fifteenth century, there was no trace of the Christian church south of the Sahara. According to William Lane, s.j.: It was not until the end of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that Christianity began to spread to the more southerly areas of Africa. The Portuguese, in their search for a sea route to India, set up bases along the East and West African coasts. Since Portugal was a Christian country, mis- sionaries followed in the wake of the traders with the aim of spreading the Gospel and setting up the Church along the African coasts.1 Prince Henry the Navigator (1394–1460) of Portugal was the man behind these expeditions, in which priests “served as chaplains to the new trading settle- ments and as missionaries to neighboring African people.”2 Hence, at the close of the sixteenth century, Christian missionary work had increased significantly south of the Sahara. In Central Africa, and more specifically in the Kingdom of Kongo, the Gospel was preached to the king and his royal family as early as 1484. -

Barotse Floodplain

Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA DETAILED ASSESSMENT, CONCEPTUAL DESIGN AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) STUDY Public Disclosure Authorized FOR THE IMPROVED USE OF PRIORITY TRADITIONAL CANALS IN THE BAROTSE SUB-BASIN OF THE ZAMBEZI ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT Public Disclosure Authorized ASSESSMENT Final Report October 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized 15 juillet 2004 BRL ingénierie 1105 Av Pierre Mendès-France BP 94001 30001 Nîmes Cedex5 France NIRAS 4128 , Mwinilunga Road, Sunningdale, Zambia Date July 23rd, 2014 Contact Eric Deneut Document title Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for the improved use of priority canals in the Barotse Sub-Basin of the Zambezi Document reference 800568 Code V.3 Date Code Observation Written by Validated by May 2014 V.1 Eric Deneut: ESIA July 2014 V.2 montage, Environmental baseline and impact assessment Charles Kapekele Chileya: Social Eric Verlinden October 2014 V.3 baseline and impact assessment Christophe Nativel: support in social baseline report ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE IMPROVED USE OF PRIORITY TRADITIONAL CANALS IN THE BAROTSE SUB-BASIN OF THE ZAMBEZI Table of content 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 2 1.1 Background of the project 2 1.2 Summary description of the project including project rationale 6 1.2.1 Project rationale 6 1.2.2 Summary description of works 6 1.3 Objectives the project 7 1.3.1 Objectives of the Assignment 8 1.3.2 Objective of the ESIA 8 1.4 Brief description of the location 10 1.5 Particulars of Shareholders/Directors 10 1.6 Percentage of shareholding by each shareholder 10 1.7 The developer’s physical address and the contact person and his/her details 10 1.8 Track Record/Previous Experience of Enterprise Elsewhere 11 1.9 Total Project Cost/Investment 11 1.10 Proposed Project Implementation Date 12 2. -

Capturing Views of Men, Women and Youth on Agricultural Biodiversity

Capturing views of men, women and youth on agricultural biodiversity resources consumed in Barotseland, Zambia CAPTURING VIEWS OF MEN, WOMEN AND YOUTH ON AGRICULTURAL BIODIVERSITY RESOURCES CONSUMED IN BAROTSELAND, ZAMBIA IN BAROTSELAND, BIODIVERSITY RESOURCES CONSUMED ON AGRICULTURAL YOUTH AND WOMEN VIEWS OF MEN, CAPTURING CAPTURING VIEWS OF MEN, WOMEN AND YOUTH ON AGRICULTURAL BIODIVERSITY RESOURCES CONSUMED IN BAROTSELAND, ZAMBIA Authors Joseph Jojo Baidu-Forson,1 Sondo Chanamwe,2 Conrad Muyaule,3 Albert Mulanda,4 Mukelabai Ndiyoi5 and Andrew Ward6 Authors’ Affiliations 1 Bioversity International (corresponding author: [email protected]) 2 Lecturer, Natural Resources Development College, Lusaka, Zambia 3 WorldFish and AAS Hub in Mongu, Zambia 4 Caritas, Mongu Diocese, Zambia 5 Lecturer, University of Barotseland, Mongu, Zambia 6 WorldFish, Africa Regional Office, Lusaka, Zambia Citation This publication should be cited as: Baidu-Forson JJ, Chanamwe S, Muyaule C, Mulanda A, Ndiyoi M and Ward A. 2015. Capturing views of men, women and youth on agricultural biodiversity resources consumed in Barotseland, Zambia. Penang, Malaysia: CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems. Working Paper: AAS-2015-17. Acknowledgments The authors would like to express sincere thanks to the indunas (community heads) for granting permission for the studies to be conducted in their communities. The authors are indebted to the following colleagues whose comments and suggestions led to improvements upon an earlier draft: Steven Cole, Mwansa Songe, Mike Phillips and Tendayi Maravanyika, all of WorldFish-Zambia; and Mauricio Bellon, Simon Attwood and Vincent Johnson of Bioversity International. We are grateful to Samantha Collins (Bioversity Communications Unit) for painstakingly editing the manuscript. -

Seasonal Food Availability

Pasqualino, M., Kennedy, G. and Nowak, V. Bioversity International SEASONAL FOOD AVAILABILITY Barotse Floodplain System 16 July 2015 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 2 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. 2 Discussion................................................................................................................................... 4 Energy ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Protective ............................................................................................................................... 5 Vitamin A-rich food ............................................................................................................. 5 Dark green leafy vegetables .............................................................................................. 5 Other vegetables ................................................................................................................ 6 Other fruits ......................................................................................................................... 6 Body-building ......................................................................................................................... 6 Animal-source food ........................................................................................................... -

But Why 1890 to 1914? 1890 Was the Year When Cecil Rhodes Managed

But why 1890 to 1914? 1890 was the year when Cecil Rhodes managed at last to consolidate his empire north of the Zambezi. In 1914, though the lights did not go out all over Africa, they were sufficiently dimmed by war and the subsequent economic depression to halt die initial impetus of development in Rhodesia. These twenty-four years were surely the most essential in Zambia’s progress into the modern world. The dialectical historian of Africa might ascribe this progress simply to copper; another might say that it was due to the northward thrust of the railway; or to the swift advance of tropical medicine, combating the tsetse and mosquito; yet another to the establishment of sound adminstration founded on missionary endeavour. The more discerning might ascribe it to the happy coincidence of all these factors, galvanised by the energy of Rhodes, that “brooding spirit”, as Kipling called him; for northern Rhodesia fell astride die highway of his dream. Let us look at Rhodes’s incursion north of die Zambezi and then briefly at some of these main forces, and, where possible, interrelate them. In 1890 his empire ended on the shores of the great river barrier of the Zambezi. North-west are the low swampy plains of Barotseland and the Kafue basin, and to the north-east the plateau that extends down through east Africa and continues on to Natal. Like the traders and explorers, including Livingstone himself, the earliest missionaries entered northern Rhodesia from Bechuanaland or Lobengula’s country, where, by the Rudd Concession of 1888, Rhodes had forced the Chief to grant him the full mineral rights of his kingdom. -

The Ends of Slavery in Barotseland, Western Zambia (C.1800-1925)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Hogan, Jack (2014) The ends of slavery in Barotseland, Western Zambia (c.1800-1925). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/48707/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html The ends of slavery in Barotseland, Western Zambia (c.1800-1925) Jack Hogan Thesis submitted to the University of Kent for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2014 Word count: 99,682 words Abstract This thesis is primarily an attempt at an economic history of slavery in Barotseland, the Lozi kingdom that once dominated the Upper Zambezi floodplain, in what is now Zambia’s Western Province. Slavery is a word that resonates in the minds of many when they think of Africa in the nineteenth century, but for the most part in association with the brutalities of the international slave trades. -

Traditional Environmental Knowledge Among Lozi Adults in Mitigating Climate Change in the Barotse Plains of Western Zambia

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 2, Issue 9, September 2015, PP 222-239 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) www.arcjournals.org Traditional Environmental Knowledge among Lozi Adults in Mitigating Climate Change in the Barotse Plains of Western Zambia Stephen Banda, Charles M. Namafe, Wanga W. Chakanika The University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia [email protected] Abstract: The background to this study had its genesis from the fact that little was known about the role of traditional environmental knowledge among Lozi adults in mitigating climate change in the Barotse plains of Mongu District, western Zambia. The study was guided by the following objectives: i) to find out how communities in Lealui area in the Barotse plains of Mongu District have been affected by climate change; ii) to assess the role of traditional environmental knowledge among Lozi adults in mitigating climate change in the Barotse plains of Mongu District; and iii) to establish what can be done to enhance traditional environmental knowledge in the Barotse plains of Mongu District to mitigate climate change. This research was a case study. It was conducted in Lealui Ward area in the Barotse plains of Mongu District, western Zambia. Mongu is located in Western Province of Zambia. The sample consisted of one hundred and twenty (130) subjects drawn from the target population: one hundred (100) indigenous Lozi adult respondents who utilize the Barotse plains in Lealui Ward, fifteen (25) local leaders like village headmen and senior traditional leaders known as area indunas, as well as five (5) institutions that provide education in environmental sustainability to mitigate climate change in Mongu District. -

Identity, Catholicism, and Lozi Culture in Zambia's Western

IDENTITY, CATHOLICISM, AND LOZI CULTURE IN ZAMBIA’S WESTERN PROVINCE BY BRADLEY JOHNSON A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Religion May 2012 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Nelly van Doorn-Harder, Ph.D., Advisor Simeon Ilesanmi, Ph.D., Chair Mary Foskett, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements I wish to express my very sincere thanks to my two advisors, Drs. Nelly van Doorn-Harder and Simeon Ilesanmi. During my short time at Wake Forest, they have always been willing to help in any capacity possible, and I have often found discussions with them to be very fruitful, both in the classroom and in their offices. I also extend my gratitude to the other professors who significantly shaped my education here: Drs. Mary Foskett, Jarrod Whitaker, Tanisha Ramachandran, Kevin Jung, Nathan Plageman, Tim Wardle, and Leon Spencer. Each one forced me to think and stretch my mind in new ways, which is one of the best gifts I can imagine. Special thanks also to the Department of Religion for helping to fund my research trip to Zambia and lifting a sizable financial burden from my family. Without the assistance, the fieldwork might not have been feasible. It is difficult to fully express my gratitude to the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate in the Western Province and Lusaka. Despite knowing me only through email correspondence and the testimony given on my behalf by a friend, they took me in and treated me with the utmost hospitality for a month and a half, eager to provide me with research opportunities along the way. -

Tears of Rain: Etnicity and History in Central Western Zambia

Tears of Rain Monographs from the African Studies Centre, Leiden Tears of Rain Ethnicity and history in central western Zambia Wim van Binsbergen Kegan Paul International London and New York INTERNET VERSION, 2004 the pagination in this version differs from that of the original printed version of 1992; the indexes have not been adjusted accordingly To Patricia First published in 1990 by Kegan Paul International Limited PO Box 256, London WC1B 3SW Distributed by International Thomson Publishing Services Ltd North Way, Andover, Hants SP10 5BE England Routledge, Chapman and Hall Inc. 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 USA The Canterbury Press Pty Ltd Unit 2, 71 Rushdale Street Scoresby, Victoria 3179 Australia Produced by W. Goar Klein Set in Times by W. Goar Klein/Z-Work Gouda, The Netherlands and printed in Great Britain by T J Press (Padstow) Ltd Cornwall © Afrika-Studiecentrum 1992 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Binsbergen, Wim M.J. van Tears of Rain: ethnicity and history in central western Zambia. – (Monographs from the African Studies Centre, Leiden) Title II. Series 305.86894 ISBN 071030434X US Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Binsbergen. Wim M.J. van. Tears of Rain: ethnicity and history in central western Zambia / Wim van Binsbergen xxii + 495 p. 21.6 cm. – (Monographs from the African Studies Centre, Leiden) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7103-0434-X Likota lya Bankoya–Criticism. Textual.