Autumn/Winter 2017 Volume 20 Number 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overlands House, Warkworth, Northamptonshire OX17 2AG Overlands House, Larder Cupboard

Overlands House, Warkworth, Northamptonshire OX17 2AG Overlands House, larder cupboard. Living/dining room with fireplace and wood-burning stove. Patio doors Warkworth, to the garden. Sitting room with an open fireplace. Utility room with vinyl flooring, base Northamptonshire unit with sink and worktop and plumbing for OX17 2AG washing machine. Cloakroom with wc. Landing with storage cupboard. Two double bedrooms Situated in a rural location, 4 miles and one single bedroon. Family bathroom with from Banbury, this is a spacious 3 suite comprising bath with shower over, wc and basin with storage cupboard below bedroom detached house with views over open countryside. Available Outside for a minimum term of 12 months. Large, maintained garden with views over open Garden maintenance included. Pets countryside. Large single garage and driveway considered. parking for 2 cars Location M40 (J11) 3 miles, Banbury 3 miles (Banbury Warkworth is situated on the borders of South to London Marylebone 56 minutes), Oxford 25 Northamptonshire and North Oxfordshire, miles close to both the market town of Banbury and thriving village of Middleton Cheney. The village Hall/Sun Room | Living/Dining Room | Sitting is well located for transport links with the M40 Room | Kitchen | Utility Room | 3 Bedrooms | (J11) 3 miles away and Banbury Train Station Bathroom | Garden | EPC Rating E very close. The local commercial centres of Banbury, Bicester and Oxford are also easy to get to from the village. Local amenities can be The property found in Middleton Cheney including a Co-op, Entrance hall/sun room with vinyl floor and pharmacy, newsagents, veterinary practice, Directions General doors to the kitchen and utility room. -

Cake and Cockhorse

CAKE AND COCKHORSE Banbury Historical Society Autumn 1973 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman and Magazine Editor: F. Willy, B.A., Raymond House, Bloxham School, Banbury Hon. Secretary: Assistant Secretary Hon. Treasurer: Miss C.G. Bloxham, B.A. and Records Series Editor: Dr. G.E. Gardam Banbury Museum J.S.W. Gibson, F.S.A. 11 Denbigh Close Marlborough Road 1 I Westgate Broughton Road Banbury OX 16 8 DF Chichester PO 19 3ET Banbury OX1 6 OBQ (Tel. Banbury 2282) (Chichester 84048) (Tel. Banbury 2841) Hon. Research Adviser: Hon. Archaeological Adviser: E.R.C. Brinkworth, M.A., F.R.Hist.S. J.H. Fearon, B.Sc. Committee Members J.B. Barbour, A. Donaldson, J.F. Roberts ************** The Society was founded in 1957 to encourage interest in the history of the town of Banbury and neighbouring parts of Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire. The Magazine Cake & Cockhorse is issued to members three times a year. This includes illustrated articles based on original local historical research, as well as recording the Society’s activities. Publications include Old Banbury - a short popular history by E.R.C. Brinkworth (2nd edition), New Light on Banbury’s Crosses, Roman Banburyshire, Banbury’s Poor in 1850, Banbury Castle - a summary of excavations in 1972, The Building and Furnishing of St. Mary’s Church, Banbury, and Sanderson Miller of Radway and his work at Wroxton, and a pamphlet History of Banbury Cross. The Society also publishes records volumes. These have included Clockmaking in Oxfordshire, 1400-1850; South Newington Churchwardens’ Accounts 1553-1684; Banbury Marriage Register, 1558-1837 (3 parts) and Baptism and Burial Register, 1558-1723 (2 parts); A Victorian M.P. -

Heritage Trail

SOUTH NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Introduction Middleton Cheney is one of the largest villages in South This walk is dedicated to Northamptonshire, situated in the south west of Northamptonshire - 3 miles from Banbury, 2 miles from junction 11 on the M40 and Middleton Cheney the memory of 6 miles from Brackley. Heritage Trail Leonard Jerrams & Since the relocation of large manufacturers to Banbury in the 1950s the village has developed with much new housing, however many William Wheeler. older 17th and 18th century cottages are hidden in the lanes leading away from the main roads. Originally an agricultural village which also supported a cottage textile industry, nowadays the residents are generally employed in nearby towns or commute along the M40 corridor. Northants place names are mostly Anglo-Saxon and Danish. ‘Tun’ or ‘Ton’ was the saxon word for an enclosed farm, then later a village or town. After the Norman Conquest the lords added their family name to the manor they had been awarded. Simon de Chenduit held the manor in a 12th century survey; John de Curci held a part in 1205. The name is ultimately derived from medieval latin, ‘casnetum’ (in old French becomes ‘chesnai’), which means oak grove. Originally the village was divided in two; Upper or Church Middleton Originally produced as a Millenium Project 2000 by Nancy Long. and a hamlet a quarter of a mile to the east; Lower or Nether Updated and reprinted 2016. Middleton. The village was divided in this way as early as the reign of Henry II (1154-1189). Middleton is also located near to the prehistoric track-way called Farthinghoe Nature Reserve Banbury Lane, which runs along the northern boundary. -

Brasenose Cottage, 47 High Street, Middleton Cheney, Oxfordshire, OX17

Brasenose Cottage, 47 High Street, Middleton Cheney Brasenose Cottage, 47 High Street, Middleton Cheney, On the first floor there is a spacious landing that Oxfordshire, OX17 2NX leads to the generous principal bedroom with en suite shower room, three further well-appointed bedrooms, and a family bathroom window seat A Grade II Listed semi-detached four/ and storage. five bedroom property situated in the popular village of Middleton Cheney. Outside The property is approached via a five-bar gate Banbury 3 miles (London Marylebone in under and a generous block-paved driveway providing 1 hour), Brackley 6 miles, M40 (J11) 2.5 miles, private parking for multiple vehicles. The well- Bicester 16 miles, Oxford 29 miles. maintained secluded garden features a lawn and a terrace area which is surrounded by mature Porch/Boot room | Kitchen/breakfast room trees, a pond and some mature shrubs and Family room | Dining room | Sitting room | trees. There is also a summer house and double Utility room/cloakroom | Ground floor bedroom garage with an adjoining log store. 5/Gym/Office | Principal bedroom with en-suite shower room | Three further double bedrooms Location Bathroom | Double garage | Off-road parking Middleton Cheney lies approximately three Garden | EPC Rating TBC miles east of Banbury. and is positioned on the borders of North Oxfordshire and South The Property Northamptonshire, it is a popular and active Brasenose Cottage is a substantial Grade II village. Village amenities include a library, Listed four-bedroom property positioned in Co-op, pharmacy, post office, bus service, the heart of the popular village of Middleton newsagents, cafe, beauticians, hair dressers, fish Cheney. -

Long Cottage, Marston St. Lawrence, Banbury, Northamptonshire Long Cottage, Outside Marston St

Long Cottage, Marston St. Lawrence, Banbury, Northamptonshire Long Cottage, Outside Marston St. Walled garden to rear with mature shrubs and trees which the landlord's gardener maintains. Lawrence, Banbury, The tenant is responsible for mowing and Northamptonshire edging of borders. Single open garage. Two outbuildings ideal for storage. Utility room with OX17 2DA shelved storage and space for a tumble dryer A delightful Grade II listed thatched Location cottage situated on the edge of the village. Part garden maintenance Marston St. Lawrence is a very popular and included. Available for a minimum attractive village five miles north east of term of 12 months. Pets by negotiation Banbury on the Oxfordshire/Northamptonshire border. Traditional village with mainly stone built period properties and a parish church surrounded by unspoilt countryside with plenty M40 (J11) 4 miles, Banbury 5 miles, Brackley of public footpaths and bridleways. 5 miles, Oxford 23 miles, London 82 miles, Banbury to London Marylebone 56 minutes Nearby Middleton Cheney has good local shops ENTRANCE HALL | SITTING ROOM | DINING and amenities. Comprehensive shopping ROOM | KITCHEN/BREAKFAST ROOM | facilities in the market towns of Banbury UTILITY ROOM/CLOAKROOM | 3 BEDROOMS | and Brackley. Local primary and secondary FAMILY BATHROOM | SEPARATE WC | SINGLE schools at Middleton Cheney and Brackley and OPEN GARAGE | 2 OUTBUILDINGS | WALLED independent schools at Brackley, Westbury and GARDEN Overthorpe, Stowe, Bloxham and Tudor Hall. Leisure facilities include racing at Towcester, Directions General EPC Rating E Cheltenham, Stratford and Warwick, polo at Kirtlington Park, Southam and Cirencester Park, From J11 of the M40 take the A422 east. At the Local Authority: South Northants DC motor racing at Silverstone and theatres in Middleton Cheney roundabout take the 2nd Services: Mains electricity, water and drainage. -

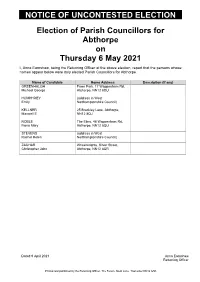

Notice of Uncontested Elections

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Election of Parish Councillors for Abthorpe on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Abthorpe. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) GREENHALGH Fawe Park, 17 Wappenham Rd, Michael George Abthorpe, NN12 8QU HUMPHREY (address in West Emily Northamptonshire Council) KELLNER 25 Brackley Lane, Abthorpe, Maxwell E NN12 8QJ NOBLE The Elms, 48 Wappenham Rd, Fiona Mary Abthorpe, NN12 8QU STEVENS (address in West Rachel Helen Northamptonshire Council) ZACHAR Wheelwrights, Silver Street, Christopher John Abthorpe, NN12 8QR Dated 9 April 2021 Anna Earnshaw Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, The Forum, Moat Lane, Towcester NN12 6AD NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Election of Parish Councillors for Ashton on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Ashton. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BULLOCK Old Manor Farm House, Roade Peter Charles Hill, Ashton, Northants, NN7 2JH DAY 8D Hartwell Road, Ashton, NN7 Bernard Ralph 2JR MCALLISTER (address in West Northants) Sarah Ann ROYCHOUDHURY `Wits End`, 8B Hartwell Road, Jeremy Sonjoy Ashton, Northamptonshire, NN7 2JR SHANAHAN (address in West Independent Neil Northamptonshire Council) Dated 9 April 2021 Anna Earnshaw Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, The Forum, Moat Lane, Towcester NN12 6AD NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Election of Parish Councillors for Aston Le Walls on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Aston Le Walls. -

All Saints Church ~ Middleton Cheney

ALL SAINTS MESSENGER nd th SUNDAY 22 JULY 2018 SUNDAY 29 JULY 2018 10.30am Holy Communion 10.45am United Benefice Communion at Chacombe A very warm welcome to All Saints. If you are a visitor, we do extend a particularly warm welcome to you and if you would like any help or more information about the church or the services then please speak to one of the welcome team. Back Supports and large print copies of hymns are available, as well as in induction hearing loop – please ask for details of how to make use of this. Toilets & baby changing facilities are located at the back of the church under the bell tower. Children are very welcome at all our services and there are activities available for them. If you have young children, please ask for a ‘pew bag’ which contains some specific toys/activities for them. Please check the notices for children’s’ activities. REGULAR ACTIVITIES WEDNESDAYS THE JOLLY TEAPOT 11am -1.00pm You'll see this sign hanging on the gate of All Saints every Wednesday morning, when the Church is open from 11.00am until 1.00pm. Come in for a chat and coffee and cake, (or tea). It's also a good opportunity for visitors to look round the Church and avail themselves of the printed guides, or for people to bring food items for the Salvation Army Food Bank. Some people may just want to sit quietly. All will be welcome. Donations for coffee go to All Saints Church Funds. HOLY COMMUNION 10.30am Monthly Midweek Holy Communion – Normally first Wednesday in the month, in Church through the summer, switching to house based in October. -

The Old Rectory Thenford | South Northamptonshire | OX17 2BX the OLD RECTORY

The Old Rectory Thenford | South Northamptonshire | OX17 2BX THE OLD RECTORY A stunning country home in a most sought-after village setting which has been completely modernised by the current owners and comprises entrance hall, kitchen, utility room, cloakroom/WC, two reception rooms with wood burning stoves, four/five bedrooms, one with large en-suite, and immaculate garden. A stunning home in a most sought-after village setting which has been fully refurbished by the current owners to provide a wonderful country residence. The current owners have spared no expense in bringing The Old Rectory up to the highest of standards with high end appliances and fittings throughout, whilst still retaining many character features. Upon entering, stairs rise to the first floor and access is afforded to the adjacent rooms. The re-fitted kitchen has been finished with high end appliances and has ample workspace, a central island, integrated fridge/freezer and dishwasher, sink unit with filtered and boiling water settings, Smeg rangemaster oven, feature display cabinet, tiled flooring, a window to the front and access to a useful pantry. The utility room has a hidden laundry area with space for appliances as well as a large storage cupboard, Belfast sink unit and a door which leads to the front garden. Access is provided to the cloakroom/WC which has a cupboard that houses a recently installed megaflow system. The dining room has exposed beams, feature display cupboards, a new wood burning stove in a feature brick surround, a window to the front with shutters and window seat and space for a table to seat eight guests. -

Middleton Cheney Heritage Trail Be a Derivation of ‘Wash Hole,’ in Times Gone by Villages Did Their Annual Laundry in the Stream That Ran Along the Bottom of the Hill

SOUTH NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Introduction Middleton Cheney is one of the largest villages in South This walk is dedicated to Northamptonshire, situated in the south west of Northamptonshire - 3 miles from Banbury, 2 miles from junction 11 on the M40 and Middleton Cheney the memory of 6 miles from Brackley. Heritage Trail Leonard Jerrams & Since the relocation of large manufacturers to Banbury in the 1950s the village has developed with much new housing, however many William Wheeler. older 17th and 18th century cottages are hidden in the lanes leading away from the main roads. Originally an agricultural village which also supported a cottage textile industry, nowadays the residents are generally employed in nearby towns or commute along the M40 corridor. Northants place names are mostly Anglo-Saxon and Danish. ‘Tun’ or ‘Ton’ was the saxon word for an enclosed farm, then later a village or town. After the Norman Conquest the lords added their family name to the manor they had been awarded. Simon de Chenduit held the manor in a 12th century survey; John de Curci held a part in 1205. The name is ultimately derived from medieval latin, ‘casnetum’ (in old French becomes ‘chesnai’), which means oak grove. Originally the village was divided in two; Upper or Church Middleton Originally produced as a Millenium Project 2000 by Nancy Long. and a hamlet a quarter of a mile to the east; Lower or Nether Updated and reprinted 2014. Middleton. The village was divided in this way as early as the reign of Henry II (1154-1189). Middleton is also located near to the prehistoric track-way called Farthinghoe Nature Reserve Banbury Lane, which runs along the northern boundary. -

An Exclusive Development of Ten Homes in the Beautiful South Northamptonshire Village of Middleton Cheney the Development

AN EXCLUSIVE DEVELOPMENT OF TEN HOMES IN THE BEAUTIFUL SOUTH NORTHAMPTONSHIRE VILLAGE OF MIDDLETON CHENEY THE DEVELOPMENT CHENEY PARK IS A STUNNING DEVELOPMENT COMPRISING ONLY TEN PLOTS OF FOUR INDIVIDUALLY DESIGNED HOUSE STYLES. The four house styles are all spacious four or five bedroom homes with considered layouts offering capacious and versatile living accommodation. Middleton Cheney is a pretty English village, and one of the largest in south Northamptonshire. Originally an agricultural village, with many workers cottages built of local Northamptonshire stone, which have helped to create the stunning milieu for Cheney Park. Middleton Cheney offers excellent transportation links to Oxford (30 miles via M40), Banbury (3 miles via A422) and Brackley (only 7 miles via A422). Additionally the A43 and M1 are also within close proximity. Regular trains into London Marylebone or into Oxford are available directly from Banbury or nearby King's Sutton: • King's Sutton to London Marylebone (1 hour 11 mins) • King's Sutton to Oxford (23 mins) • Banbury to London Marylebone (54 mins) • Banbury to Oxford (19 mins) 2 CHENEY PARK | BARWOOD HOMES CHENEY PARK | BARWOOD HOMES 3 PLOT 6: PLOT 5: PLOT 10: THE BUCKINGHAM THE SANDRINGHAM THE BUCKINGHAM PLOT 4: PLOT 3: THE WOBURN THE ALTHORP PLOT 7: THE ALTHORP PLOT 2: THE BUCKINGHAM This is an artistic interpretation of CHENEY PARK. Therefore, variations in finishes and exact layout may not be accurate. Please ask your sales person for the complete specification. Images are for illustrative purposes only. PLOT 8: PLOT 9: PLOT 1: 4 CHENEY PARK | BARWOOD HOMES THE BUCKINGHAM THE ALTHORP THE WOBURN LOCAL AREA THE VILLAGE HAS AN IMPRESSIVE ARRAY OF LOCAL AMENITIES WHICH CONTRIBUTE TO THE STRONG COMMUNITY SPIRIT AND WELCOMING VIBE. -

Marston Road, Greatworth Banbury Oxon OX17 2EA 7 Marston Road Greatworth Banbury Oxon OX17 2EA

Marston Road, Greatworth Banbury Oxon OX17 2EA 7 Marston Road Greatworth Banbury Oxon OX17 2EA * Detached Village Home * 4 Double Bedrooms * Master with En-suite and Walk- in Wardrobe * Lounge * Dining Room * Kitchen/Breakfast Room * Utility * Family Room * Oversized Double Garage * Guide price £475,000 Freehold A large detached modern home situated on the edge of this sought after village with views of fields to the front. • Brackley Town Centre: 6.7 miles • Banbury Station: 8.8 miles • Bicester North Station: 16.2 miles • Milton Keynes City Centre: 26.0 miles Viewings by prior appointment through Macintyers 01280 701001 GROUND FLOOR The spacious reception hall has glazed double doors to the dining GREATWORTH room, glazed doors to the lounge and kitchen/breakfast room and A popular South panelled doors to the cloakroom and coat cupboard. Stairs rise to the Northamptonshire village to the first floor with a cupboard beneath. The dining room is a large room West of Brackley. looking to the front. The lounge has two sets of French doors leading Predominantly stone-built and out to the rear garden and an open fireplace. The kitchen/breakfast centred around the Shop/Post room is fitted with wooden fronted cupboards with worktops over and Office, Primary School, Public two windows overlook fields to the front. Built-in appliances include a House and Church. Secondary double oven, a 4-ring hob with a hood over, fridge/freezer and education is at 'Chenderit dishwasher. There is space for a table and an arch leads to the family School' in the nearby village of room which has French doors out to the rear garden and a door to the Middleton Cheney. -

St Martins House Northamptonshire/Oxfordshire Borders

St Martins House Northamptonshire/Oxfordshire borders St Martins House Warkworth, Northamptonshire/Oxfordshire borders Middleton Cheney 1.5 miles, Banbury station (trains to London Marylebone 58 minutes) 2.5 miles, Kings Sutton 3.5 miles, Soho Farmhouse 15 miles, Bicester 20 miles, Oxford 30 miles (all times and distances are approximate) A substantial family house with spacious open plan living, generous ceiling heights within striking distance of Banbury. Entrance hall | Drawing room | Sitting room | Kitchen/breakfast room Utility room | Cloakroom | Boiler room 4 Bedrooms | 3 Bath/shower rooms (2 ensuite) Separate annexe | Double garage | Workshop | Office | WC | Store Knight Frank Oxford 274 Banbury Road Oxford, OX2 7DY 01865 264 879 [email protected] knightfrank.co.uk St Martins House St Martins House is a substantial family house with versatile accommodation and several purposeful outbuildings. Built of local iron stone under a slate roof the house has been sympathetically extended to accommodate modern family living. Internally, the main reception rooms are well proportioned, light and spacious with generous ceiling heights and an open plan modern feel. The drawing room is center on an impressive fireplace and the vaulted ceiling makes the room a wonderful entertaining space. The adjoining kitchen/breakfast room is near 30th long with French doors out to the garden. There are multiple wall and base units and a sizeable utility room and cloakroom beyond. The bedroom accommodation is conveniently divided with the master suite on the ground floor and three bedrooms and two bath/showers room above. Outside, the gardens private and secure behind electric gates. There is a barbecue area on timber decking, a separate one bedroom annexe and a double garage with adjoining home office.