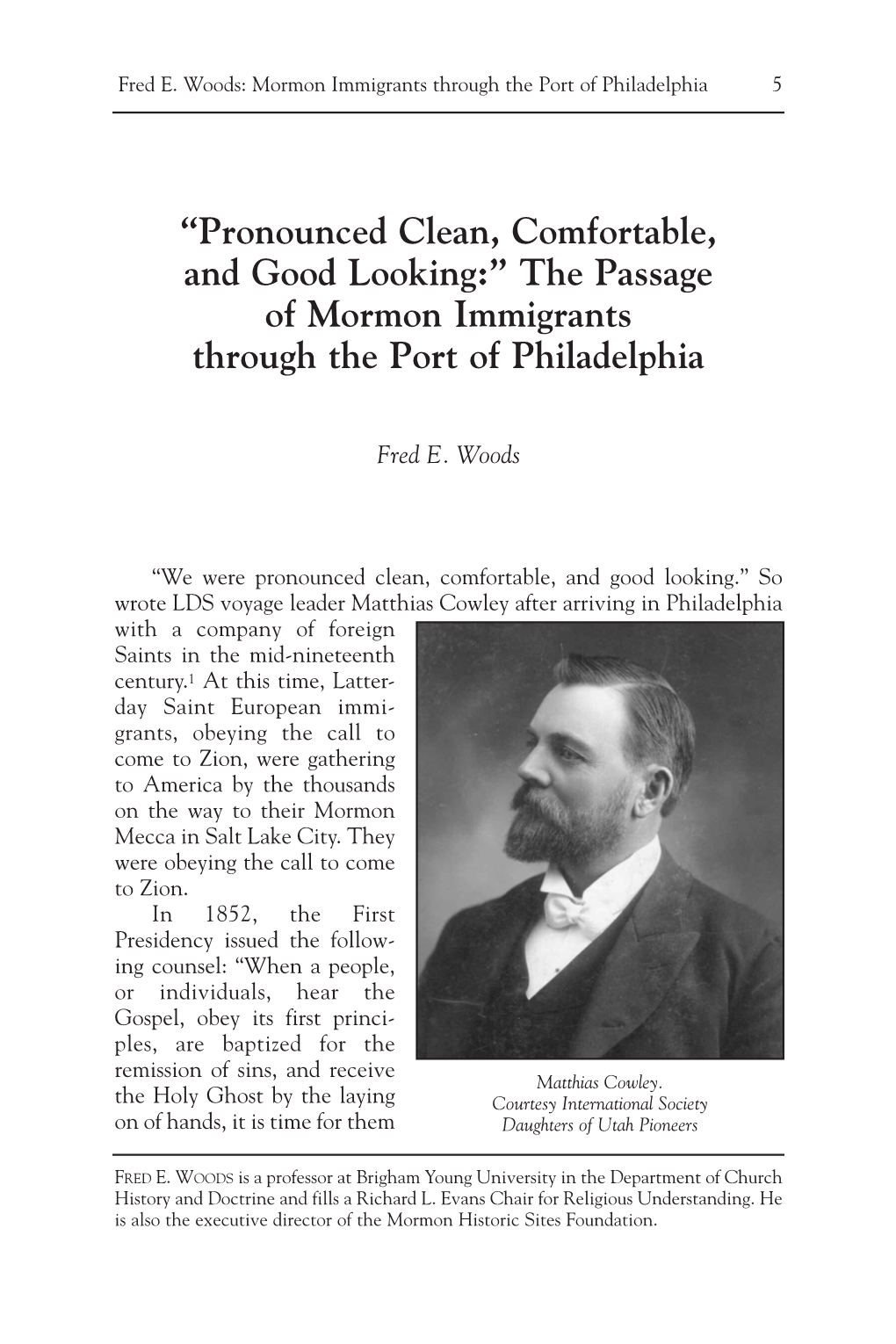

The Passage of Mormon Immigrants Through the Port of Philadelphia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Smith Retouched Photograph of a Dagurreotype

07 the joseph smith retouched photograph0 of a dagurreotypedaguerreotype of a painting or copy of daguerrotypedaguerreotype from the carter collection LDS church archives parting the veil the visions of joseph smith alexander L baugh godgrantedgod granted to the prophetjosephprophet joseph thegiftthe gift of visions joseph received so many that they became almost commonplacecommonplacefor for him the strength and knowledge joseph received through these visions helped him establish the church joseph smith the seer ushered in the dispensation of the fullness of times his role was known and prophesied of anciently the lord promised joseph of egypt that in the last days a choice seer would come through his lineage and would bring his seed to a knowledge of the covenants made to abraham isaac and jacob 2 nephi 37 JST gen 5027 28 that seer will the lord bless joseph prophesied specifically indicating that his name shall be called after me 2 nephi 314 15 see also JST gen 5033 significantly in the revelation received during the organizational meeting of the church on april 61830 the first title given to the first elder was that of seer behold there shall be a record kept and in it thou joseph smith shalt be called a seer a translator a prophet an apostle of jesus christ dacd&c 211 in the book of mormon ammon defined a seer as one who possessed a gift from god to translate ancient records mosiah 813 see also 2811 16 however the feericseeric gift is not limited to translation hence ammon s addi- tional statement that a seer is a revelator and a -

“For This Ordinance Belongeth to My House”: the Practice of Baptism for the Dead Outside the Nauvoo Temple

Alexander L. Baugh: Baptism for the Dead Outside Temples 47 “For This Ordinance Belongeth to My House”: The Practice of Baptism for the Dead Outside the Nauvoo Temple Alexander L. Baugh The Elders’ Journal of July 1838, published in Far West, Missouri, includ- ed a series of twenty questions related to Mormonism. The answers to the questions bear the editorial pen of Joseph Smith. Question number sixteen posed the following query: “If the Mormon doctrine is true, what has become of all those who have died since the days of the apostles?” The Prophet answered, “All those who have not had an opportunity of hearing the gospel, and being administered to by an inspired man in the flesh, must have it hereafter before they can be finally judged.”1 The Prophet’s thought is clear—the dead must have someone in mortality administer the saving ordinances for them to be saved in the kingdom of God. Significantly, the answer given by the Prophet marks his first known statement concerning the doctrine of vicari- ous work for the dead. However, it was not until more than two years later that the principle was put into practice.2 On 15 August 1840, Joseph Smith preached the funeral sermon of Seymour Brunson during which time he declared for the first time the doc- trine of baptism for the dead.3 Unfortunately, there are no contemporary accounts of the Prophet’s discourse. However, Simon Baker was present at the funeral services and later stated that during the meeting the Prophet read extensively from 1 Corinthians 15, then noted a particular widow in the congregation whose son had died without baptism. -

Joseph Smith's Lessons on Leadership

Education Week 2015 Prepare for “Joseph Smith’s Lessons on Leadership” Taught by Robert Spiel Retrieved from: http://josephsmith.net/article/leading-with-love?lang=eng Introduction Joseph Smith was a remarkable leader. He served as President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; mayor of Nauvoo, one of the largest cities in Illinois; lieutenant-general of the Nauvoo Legion; and in 1844 he was a candidate for President of the United States. What set Joseph Smith apart from other dynamic leaders was the source of his teachings: the God of Heaven. "The best way to obtain truth 1 and wisdom," he taught, "is not to ask it from books, but to go to God in prayer, and obtain divine teaching." 2 Joseph led with love. He recognized the worth of every soul as a child of God. When asked why so many followed him, he replied: "It is because I possess the principle of love. All I can offer the world is a good heart and a good hand." 3 The Prophet refused to place himself above others. Rather, as he humbly said, "I love to wait upon the Saints, and be a servant to all, hoping that I may be exalted in the due time of the Lord." 4 Bereft of pride, 5 Joseph personified the Lord's counsel: "Whosoever will be great among you, . shall be servant of all." 6 Joseph Smith Quotes Nothing is so much calculated to lead people to forsake sin as to take them by the hand, and watch over them with tenderness. -

1864 Minutes of the Annual Conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, for the Year 1864 Methodist Episcopal Church, South

Asbury Theological Seminary ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange Conference Journals Methodist Episcopal Church, South 2017 1864 Minutes of the Annual Conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, for the Year 1864 Methodist Episcopal Church, South Follow this and additional works at: http://place.asburyseminary.edu/mechsouthconfjournals Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Genealogy Commons Recommended Citation Methodist Episcopal Church, South, "1864 Minutes of the Annual Conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, for the Year 1864" (2017). Conference Journals. 20. http://place.asburyseminary.edu/mechsouthconfjournals/20 This Periodical/Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Conference Journals by an authorized administrator of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL CONFERENCES OF THE FOR THE YEAR 1864 . • I •• ,. ~lu~billtt ~tnn.: SOUTHERN !\IETHODIST PUBLISHING HOUSE. 1870. BISHOPS OF THE lIETHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH, SOUTH. JQSHUA SOULE, D. D., NASHVILLE, T ENN. JAMES OSGOOD ANDRE 'V, D. D., SUMMERFIELD, ALA. ROBERT P ArNE, D. D., ABERDEEN, MISS. GEORGE FOSTER PIERC1E, D. D., CULVERTON, GA. JOHN EARLY, D. D., LYNCHBURG, VA. HUBBARD HINDE KAVANAUGH, D. D., VERSAILLES, Ky. MINUTES. '1. I.-KENTUCKY CONFERENCE. HELD AT MAYSVILLE, Ky., September 7-12, 1864. J. C. HARRISON, Prewidentj DANIEL STEVENSON, Secretary. QUESTION 1. Who are admitted on trial? William Atherton. 1. ANSWER. Daniel M. Bonner. 1. No memoir. Ques. 2. Who remain on trial? Ques. 15. Are all the preachers blameless in J. -

Full Journal

Advisory Board Noel B. Reynolds, chair Grant Anderson James P. Bell Donna Lee Bowen Involving Readers Douglas M. Chabries Neal Kramer in the Latter-day Saint John M. Murphy Academic Experience Editor in Chief John W. Welch Church History Board Richard Bennett, chair 19th-century history Brian Q. Cannon 20th-century history Kathryn Daynes 19th-century history Gerrit J. Dirkmaat Joseph Smith, 19th-century Mormonism Steven C. Harper documents Frederick G. Williams cultural history Liberal Arts and Sciences Board Barry R. Bickmore, chair geochemistry Justin Dyer family science, family and religion Daryl Hague Spanish and Portuguese Susan Howe English, poetry, drama Steven C. Walker Christian literature Reviews Board Gerrit van Dyk, chair Church history Trevor Alvord new media Herman du Toit art, museums Specialists Casualene Meyer poetry editor Thomas R. Wells photography editor Ashlee Whitaker cover art editor STUDIES QUARTERLY BYU Vol. 57 • No. 3 • 2018 ARTICLES 4 From the Editor 7 Reclaiming Reality: Doctoring and Discipleship in a Hyperconnected Age Tyler Johnson 39 Understanding the Abrahamic Covenant through the Book of Mormon Noel B. Reynolds 81 The Language of the Original Text of the Book of Mormon Royal Skousen 111 Joseph Smith’s Iowa Quest for Legal Assistance: His Letters to Edward Johnstone and Others on Sunday, June 23, 1844 John W. Welch 143 Martin Harris Comes to Utah, 1870 Susan Easton Black and Larry C. Porter ESSAY 75 Wandering On to Glory Patrick Moran POETRY 80 Anaranjado John Alba Cutler 165 “Why Are Your Kids Late to School Today?” Lisa Martin BOOK REVIEWS 166 Saints at Devil’s Gate: Landscapes along the Mormon Trail by Laura Allred Hurtado and Bryon C. -

The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1960 The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History James N. Baumgarten Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Baumgarten, James N., "The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History" (1960). Theses and Dissertations. 4513. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4513 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 3 e F tebeebTHB ROLEROLB ardaindANDAIRD FUNCTION OF tebeebTHB SEVKMTIBS IN LJSlasLDS chweceweCHMECHURCH HISTORYWIRY A thesis presentedsenteddented to the dedepartmentA nt of history brigham youngyouyom university in partial ftlfillmeutrulfilliaent of the requirements for the degree master of arts by jalejamsjamejames N baumgartenbelbexbaxaartgart9arten august 1960 TABLE CFOF CcontentsCOBTEHTS part I1 introductionductionreductionroductionro and theology chapter bagragpag ieI1 introduction explanationN ionlon of priesthood and revrevelationlation Sutsukstatementement of problem position of the writer dedelimitationitationcitation of thesis method of procedure and sources II11 church doctrine on the seventies 8 ancient origins the revelation -

Opening the Heavens: Seventy-Six Accounts of Joseph Smith's

Desk in the room of the restored John Johnson home, Hiram, Ohio, in which “The Vision,” now known as Doctrine and Covenants 76, was received con- currently by Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon. Courtesy John W. Welch. Seventy-six Accounts of Joseph Smith’s Visionary Experiences Alexander L. Baugh oseph Smith the seer ushered in the dispensation of the fullness of Jtimes. His role was known and prophesied of anciently. The Lord promised Joseph of Egypt that in the last days a “choice seer” would come through his lineage and would bring his seed to a knowledge of the covenants made to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (2 Ne. 3:7; jst Gen. 50:27–28). “That seer will the Lord bless,” Joseph prophesied, specifi- cally indicating that “his name shall be called after me” (2 Ne. 3:14–15; see also jst Gen. 50:33). Significantly, in the revelation received dur- ing the organizational meeting of the Church on April 6, 1830, the first title given to the first elder was that of seer: “Behold, there shall be a record kept . and in it thou [Joseph Smith] shalt be called a seer, a translator, a prophet, an apostle of Jesus Christ” (D&C 21:1). In the Book of Mormon, Ammon defined a seer as one who pos- sessed “a gift from God” to translate ancient records (Mosiah 8:13; see also 28:11–16). However, the seeric gift is not limited to translation, hence Ammon’s additional statement that “a seer is a revelator and a prophet also; and a gift which is greater can no man have” (Mosiah 8:16). -

A Lady's Life Among the Mormons

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Exposé of Polygamy: A Lady's Life among the Mormons Fanny Stenhouse Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Stenhouse, T. B. H., & DeSimone, L. W. (2008). Expose ́ of polygamy: A lady's life among the Mormons. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exposé of Polygamy A Lady’s Life among the Mormons Volume 10 Life Writings of Frontier Women Used by permission, Utah State Historical Society, all rights reserved. Fanny Stenhouse. Exposé of Polygamy: A Lady’s Life among the Mormons Fanny Stenhouse Edited by Linda Wilcox DeSimone Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 2008 Copyright © 2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 www.usu.edu/usupress Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper ISBN: 978–0–87421–713–1 (cloth) ISBN: 978–0–87421–714–8 (e-book) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stenhouse, T. B. H., Mrs., b. 1829. Exposé of polygamy : a lady’s life among the Mormons / Fanny Stenhouse ; edited by Linda Wilcox DeSimone. p. cm. – (Life writings of frontier women ; v. 10) Originally published: New York : American News Co., 1872. -

Joseph Smith's Incarceration in Richmond, Missouri, November 1838

134 Mormon Historical Studies The arrest of Joseph Smith near Far West, Missouri, by C. C. A. Christensen. Baugh: Joseph Smith’s Incarceration in Richmond, Missouri 135 “Silence, Ye Fiends of the Infernal Pit!”: Joseph Smith’s Incarceration in Richmond, Missouri, November 1838 Alexander L. Baugh On October 27, 1838, after nearly three months of hostilities between Mormon and Missouri settlers in Daviess, Carroll, Ray, and Caldwell Counties, Missouri, Governor Lilburn W. Boggs signed an executive order authorizing the state militia to subdue the Mormon populace and force their surrender, and ordered them to evacuate the state.1 The order was carried out by Samuel D. Lucas, a major general in the state militia and the commander of the troops from Jackson and Lafayette Counties. The day before issuing the “Extermination Order,” Boggs relieved Major General David R. Atchison of his command of the state militia in the Northern District.2 Atchison’s release probably stemmed from the fact that he had served as legal counsel to Joseph Smith and was at least partially sympathetic of the Mormons. Boggs replaced Atchison with John B. Clark of Howard County. However, since Clark was not on the scene to take charge, Lucas assumed command. On October 31, General Lucas and his officers negotiated a peaceful, albeit unfair settlement with a five-man Mormon delegation led by George M. Hinkle, commander of the Caldwell County militia. The final conditions of surrender called for the Mormons to make an appropriation of property to cover any indemnities caused during the Missouri conflict, give up their arms, ALEX A N D ER L. -

New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol 13

^ > ^ % ^-ijffioS \j$^ j? \/^%p * \*^^*>^ % *°*V, *5* V^ (V\\ 55K //>i „ \f* ..S £==i™B=~5 *5» A - O. *• i 1 <3 V http://www.archive.org/details/newyorkgenealog13iJnewy : V °^f^" ^^. .»^° .A ^ 'SW' .^^0. -.^ INDEX TO SUBJFXTS. Address, Anniversary, of 18S2, before the N. Y. Genealogical and Biographical Society by Hon. Isaac N. Arnold, 101. Address, Memorial, of Gov. Wm. Beach Lawrence, by Genl. James Grant Wilson, 5--. American Branch of the Pruyn Family, by John V. L. Pruyn, Jr., n 71, r<;6. Anniversary before Address the N. Y. Genealogical and Biographical Society April IK F 5 ' 1882, by Hon. Isaac N. Arnold, 101. Arnold, Hon. Isaac N. Reminiscences of Lincoln and of Congress during the Rebel- lion, 101. Baird, Charles Birth W. and Marriage Records of Bedford, N. Y., 92. Baptisms in the Reformed Dutch Church in New York City, 29, 63, 131, 165. Bartow, Rev. Evelyn. English Ancestry of the Beers Family, " " " 85. Genealogy of the Prevost Family, 27. Beers Family, English Ancestry of, by Rev. Evelyn Bartow, 85. Biography of Col. Joseph Lemuel Chester. D.C.L., LL. D. , by John Latting, Esq., " J. 149. of Gov. Wm. Beach Lawrence, by Genl. James Grant Wilson, 53.' Births and Marriages, Bedford, N. Y., by Charles W. Baird, 92. Chester, Joseph L., Biographical Sketch of, by John J. Latting, Esq., 149. Clinton Family of New York, by Charles B. Moore, Esq., 5, 139, 173. Edsall Family, by Thomas Henry Edsall, Esq., 194. Edsall, Thomas H., Esq., on Fish and Fishermen in New York, " 181. " " Sketch of Edsall Family, " " 194. -

The Emergence and Development of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter–Day Saints in Staffordshire, 1839–1870

UNIVERSITY OF CHICHESTER An accredited institution of the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Department of History The Emergence and Development of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter–day Saints in Staffordshire, 1839–1870 by David Michael Morris Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy This thesis has been completed as a requirement for a higher degree of the University of Southampton November 2010 UNIVERSITY OF CHICHESTER An accredited institution of the University of Southampton ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctor of Philosophy The Emergence and Development of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter–day Saints in Staffordshire, 1839–1870 By David Michael Morris This thesis analyses the emergence, development and subsequent decline of the LDS Church in Staffordshire between 1839 and 1870 as an original contribution to nineteenth–century British regional and religious history. I begin by examining the origins of the US Mormon Mission to Britain and a social historical study of the Staffordshire religious and industrial landscape. In order to recover the hidden voices of Staffordshire Mormon converts, I have constructed a unique Staffordshire Mormon Database for the purposes of this thesis containing over 1,900 records. This is drawn upon throughout, providing the primary quantitative evidence for this fascinating yet neglected new religious movement. From the data I explore the demographic composition of Staffordshire Mormonism using a more precise definition of class than has been the case previously, whilst also considering gender and -

Mormon Movement to Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2004 Mormon movement to Montana Julie A. Wright The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Wright, Julie A., "Mormon movement to Montana" (2004). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5596. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5596 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly- cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature: Date: Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 MORMON MOVEMENT TO MONTANA by ' Julie A. Wright B.A. Brigham Young University 1999 presented in partial fulfillment o f the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University o f Montana % November 2004 Approved by: Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP41060 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.