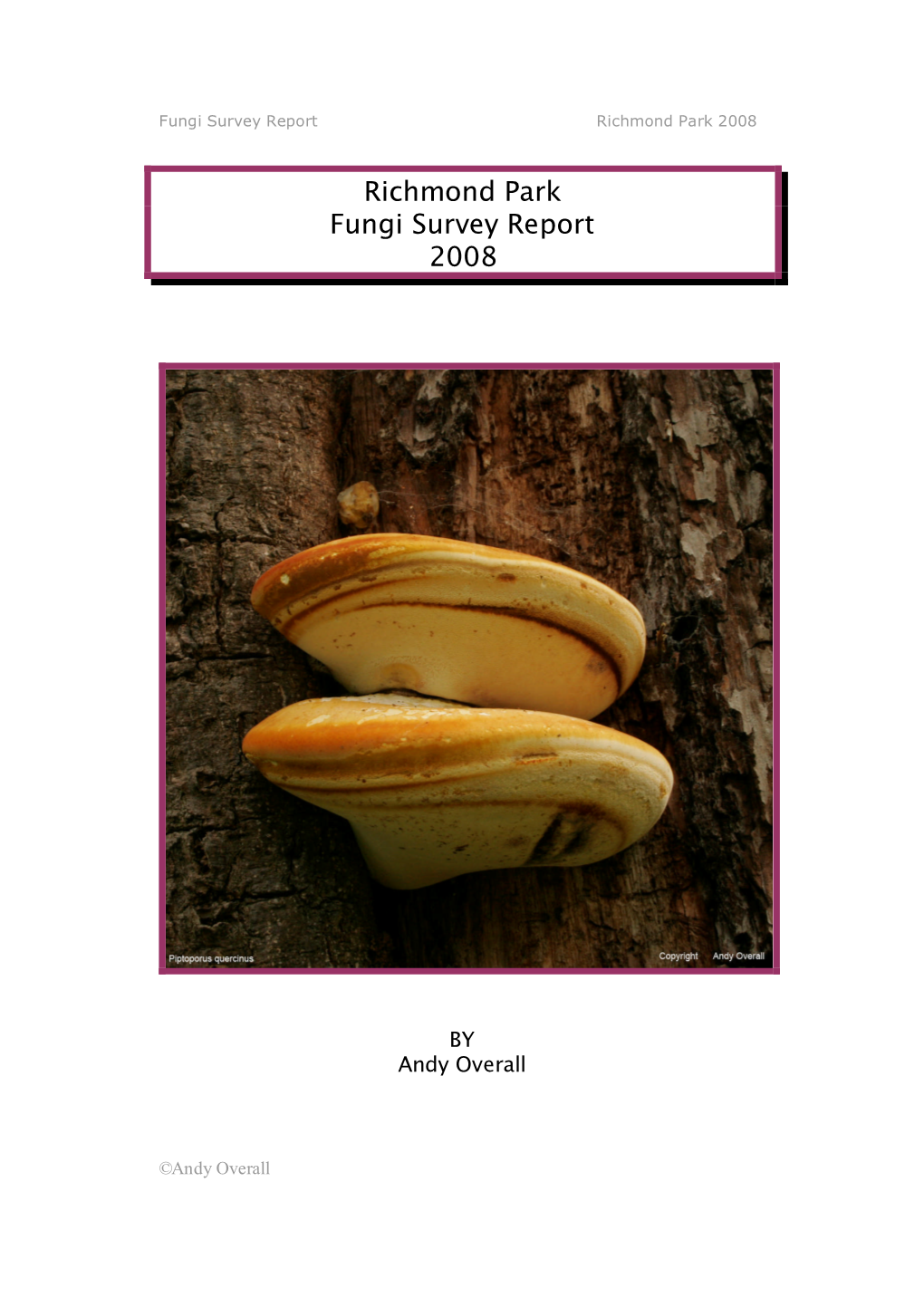

Richmond Park Fungi Survey Report 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of Argentine Agaricales 4

Checklist of the Argentine Agaricales 4. Tricholomataceae and Polyporaceae 1 2* N. NIVEIRO & E. ALBERTÓ 1Instituto de Botánica del Nordeste (UNNE-CONICET). Sargento Cabral 2131, CC 209 Corrientes Capital, CP 3400, Argentina 2Instituto de Investigaciones Biotecnológicas (UNSAM-CONICET) Intendente Marino Km 8.200, Chascomús, Buenos Aires, CP 7130, Argentina CORRESPONDENCE TO *: [email protected] ABSTRACT— A species checklist of 86 genera and 709 species belonging to the families Tricholomataceae and Polyporaceae occurring in Argentina, and including all the species previously published up to year 2011 is presented. KEY WORDS—Agaricomycetes, Marasmius, Mycena, Collybia, Clitocybe Introduction The aim of the Checklist of the Argentinean Agaricales is to establish a baseline of knowledge on the diversity of mushrooms species described in the literature from Argentina up to 2011. The families Amanitaceae, Pluteaceae, Hygrophoraceae, Coprinaceae, Strophariaceae, Bolbitaceae and Crepidotaceae were previoulsy compiled (Niveiro & Albertó 2012a-c). In this contribution, the families Tricholomataceae and Polyporaceae are presented. Materials & Methods Nomenclature and classification systems This checklist compiled data from the available literature on Tricholomataceae and Polyporaceae recorded for Argentina up to the year 2011. Nomenclature and classification systems followed Singer (1986) for families. The genera Pleurotus, Panus, Lentinus, and Schyzophyllum are included in the family Polyporaceae. The Tribe Polyporae (including the genera Polyporus, Pseudofavolus, and Mycobonia) is excluded. There were important rearrangements in the families Tricholomataceae and Polyporaceae according to Singer (1986) over time to present. Tricholomataceae was distributed in six families: Tricholomataceae, Marasmiaceae, Physalacriaceae, Lyophyllaceae, Mycenaceae, and Hydnaginaceae. Some genera belonging to this family were transferred to other orders, i.e. Rickenella (Rickenellaceae, Hymenochaetales), and Lentinellus (Auriscalpiaceae, Russulales). -

LUNDY FUNGI: FURTHER SURVEYS 2004-2008 by JOHN N

Journal of the Lundy Field Society, 2, 2010 LUNDY FUNGI: FURTHER SURVEYS 2004-2008 by JOHN N. HEDGER1, J. DAVID GEORGE2, GARETH W. GRIFFITH3, DILUKA PEIRIS1 1School of Life Sciences, University of Westminster, 115 New Cavendish Street, London, W1M 8JS 2Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD 3Institute of Biological Environmental and Rural Sciences, University of Aberystwyth, SY23 3DD Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The results of four five-day field surveys of fungi carried out yearly on Lundy from 2004-08 are reported and the results compared with the previous survey by ourselves in 2003 and to records made prior to 2003 by members of the LFS. 240 taxa were identified of which 159 appear to be new records for the island. Seasonal distribution, habitat and resource preferences are discussed. Keywords: Fungi, ecology, biodiversity, conservation, grassland INTRODUCTION Hedger & George (2004) published a list of 108 taxa of fungi found on Lundy during a five-day survey carried out in October 2003. They also included in this paper the records of 95 species of fungi made from 1970 onwards, mostly abstracted from the Annual Reports of the Lundy Field Society, and found that their own survey had added 70 additional records, giving a total of 156 taxa. They concluded that further surveys would undoubtedly add to the database, especially since the autumn of 2003 had been exceptionally dry, and as a consequence the fruiting of the larger fleshy fungi on Lundy, especially the grassland species, had been very poor, resulting in under-recording. Further five-day surveys were therefore carried out each year from 2004-08, three in the autumn, 8-12 November 2004, 4-9 November 2007, 3-11 November 2008, one in winter, 23-27 January 2006 and one in spring, 9-16 April 2005. -

Volatilomes of Milky Mushroom (Calocybe Indica P&C) Estimated

International Journal of Chemical Studies 2017; 5(3): 387-391 P-ISSN: 2349–8528 E-ISSN: 2321–4902 IJCS 2017; 5(3): 387-381 Volatilomes of milky mushroom (Calocybe indica © 2017 JEZS Received: 15-03-2017 P&C) estimated through GCMS/MS Accepted: 16-04-2017 Priyadharshini Bhupathi Priyadharshini Bhupathi and Krishnamoorthy Akkanna Subbiah PhD Scholar, Department of Plant Pathology, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Abstract Coimbatore, India The volatilomes of both fresh and dried samples of milky mushroom (Calocybe indica P&C var. APK2) were characterized with GCMS/MS. The gas chromatogram was performed with the ethanolic extract of Krishnamoorthy Akkanna the samples. The results revealed the presence of increased levels of 1, 4:3, 6-Dianhydro-α-d- Subbiah glucopyranose (57.77%) in the fresh and oleic acid (56.58%) in the dried fruiting bodies. The other Professor and Head, Department important fatty acid components identified both in fresh and dried milky mushroom samples were of Plant Pathology, Tamil Nadu octadecenoic acid and hexadecanoic acid, which are known for their specific fatty or cucumber like Agricultural University, aroma and flavour. The aroma quality of dried samples differed from that of fresh ones with increased Coimbatore, India levels of n- hexadecenoic acid (peak area - 8.46 %) compared to 0.38% in fresh samples. In addition, α- D-Glucopyranose (18.91%) and ergosterol (5.5%) have been identified in fresh and dried samples respectively. The presence of increased levels of ergosterol indicates the availability of antioxidants and anticancer biomolecules in milky mushroom, which needs further exploration. The presence of α-D- Glucopyranose (trehalose) components reveals the chemo attractive nature of the biopolymers of milky mushroom, which can be utilized to enhance the bioavailability of pharmaceutical or nutraceutical preparations. -

Tree Inspection Equipment 2013

PiCUS Tree Inspection Equipment 2013 Tree Pulling Test Sonic Tomography Dynamic Sway Motion Electric Resistance Tomography www.sorbus-intl.co.uk PiCUS Tree Inspection Equipment Description of Tree Inspection Equipment of argus electronic gmbh Contents 1. Products of argus electronic for Tree Decay Detection ............................................. 3 2. Frequently asked questions (FAQ) ........................................................................... 4 3. PiCUS Sonic Tomograph .......................................................................................... 7 3.1. Working principle ................................................................................................... 7 3.2. How to record a sonic tomogram .......................................................................... 8 3.3. Determining the measuring level ........................................................................... 8 3.4. Measuring the geometry of the tree at the measuring level ................................... 8 3.5. Taking sonic measurements ................................................................................. 9 3.6. Few sensors – much tomogram ............................................................................ 9 3.7. Calculating a Tomogram ....................................................................................... 9 3.8. Time lines ............................................................................................................ 10 3.9. PiCUS CrackDect - Crack Detection with the -

Forest Fungi in Ireland

FOREST FUNGI IN IRELAND PAUL DOWDING and LOUIS SMITH COFORD, National Council for Forest Research and Development Arena House Arena Road Sandyford Dublin 18 Ireland Tel: + 353 1 2130725 Fax: + 353 1 2130611 © COFORD 2008 First published in 2008 by COFORD, National Council for Forest Research and Development, Dublin, Ireland. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from COFORD. All photographs and illustrations are the copyright of the authors unless otherwise indicated. ISBN 1 902696 62 X Title: Forest fungi in Ireland. Authors: Paul Dowding and Louis Smith Citation: Dowding, P. and Smith, L. 2008. Forest fungi in Ireland. COFORD, Dublin. The views and opinions expressed in this publication belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of COFORD. i CONTENTS Foreword..................................................................................................................v Réamhfhocal...........................................................................................................vi Preface ....................................................................................................................vii Réamhrá................................................................................................................viii Acknowledgements...............................................................................................ix -

Inventory of Ectomycorrizal Fungi

PINHO-ALM EIDA F., BASÍLIO C., de OLIVEIRA P. - 1999 - Inventory of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with a "relic" holm-oak tree (Quercus rotundifolia) in two successive winters. Documents Mycologiques 29 (115) : 57 - 68 Inventory of ectomycorrizal fungi associated with a "relic" holm-oak tree (Quercus rotundifolia) in two successive winters Fátima Pinho-Almeida*, Carmo Basílio*, and Paulo de Oliveira ** *Centro de Micologia da Universidade de Lisboa, Rua da Escola Politécnica, 58, P-1250 Lisboa **Departamento de Biologia, Universidade de Évora,Apartado 4, 7002-554 ÉVORA, Portugal Abstract Holm-oak (Quercus rotundifolia), either as forests or as seminatural stands (the “montado” systems), occupies a vast area of land in Portugal, forming an important ecological and economical reserve that remains very little studied. A «relic» tree of this species, left from a montado stand that was replaced by cereals decades ago and now surrounded by Eucalyptus globulus, was visited during two winter carpophore fruiting seasons to scrutinize the ectomycorrhizal species associated with its root system. The sampled sporophores were identified and mapped relative to the oak trunk. Of thirty nine different higher fungi species that have been tentatively identified after four gatherings, twenty nine were problably ectomycorrhizal. Russula spp. (a total of ten species) dominated in the first gathering of each season while Lactarius cremor and Helvella lacunosa dominated in the second of the first and second season, respectively. Practically none of the holm oak-associated mutualistic or facultative species were found in the surrunding eucalyptus plantation. This study will be continued and extended to other locations in the long term, in order to provide data on the ecology of the holm oak ectomycorrhizal associates and to support the molecular identification of fungal isolates obtained from holm oak ectomycorrhizas. -

Full-Text (PDF)

African Journal of Microbiology Research Vol. 5(31), pp. 5750-5756, 23 December, 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJMR ISSN 1996-0808 ©2011 Academic Journals DOI: 10.5897/AJMR11.1228 Full Length Research Paper Leucocalocybe, a new genus for Tricholoma mongolicum (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) Xiao-Dan Yu1,2, Hui Deng1 and Yi-Jian Yao1,3* 1State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100101, China. 2Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100049, China. 3Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, United Kingdom. Accepted 11 November, 2011 A new genus of Agaricales, Leucocalocybe was erected for a species Tricholoma mongolicum in this study. Leucocalocybe was distinguished from the other genera by a unique combination of macro- and micro-morphological characters, including a tricholomatoid habit, thick and short stem, minutely spiny spores and white spore print. The assignment of the new genus was supported by phylogenetic analyses based on the LSU sequences. The results of molecular analyses demonstrated that the species was clustered in tricholomatoid clade, which formed a distinct lineage. Key words: Agaricales, taxonomy, Tricholoma, tricholomatoid clade. INTRODUCTION The genus Tricholoma (Fr.) Staude is typified by having were re-described. Based on morphological and mole- distinctly emarginate-sinuate lamellae, white or very pale cular analyses, T. mongolicum appears to be aberrant cream spore print, producing smooth thin-walled within Tricholoma and un-subsumable into any of the basidiospores, lacking clamp connections, cheilocystidia extant genera. Accordingly, we proposed to erect a new and pleurocystidia (Singer, 1986). Most species of this genus, Leucocalocybe, to circumscribe the unique genus form obligate ectomycorrhizal associations with combination of features characterizing this fungus and a forest trees, only a few species in the subgenus necessary new combination. -

Wood Research Wood Decay Characterization of a Naturally- Infected Oak Wood Bridge Using Py-Gc/Ms

WOOD RESEARCH 58 (4): 2013 591-598 WOOD DECAY CHARACTERIZATION OF A NATURALLY- INFECTED OAK WOOD BRIDGE USING PY-GC/MS Leila Karami, Olaf Schmidt*, Jörg Fromm, Andreas Klinberg University of Hamburg, Centre of Wood Sciences Hamburg, Germany Uwe Schmitt Thünen Institute of Wood Research, Federal Research Institute for Rural Areas, Forestry and Fisheries Hamburg, Germany (Received May 2013) ABSTRACT Decayed-wood samples were collected from a naturally-infected bridge made of Quercus robur. Fruit-bodies of the white-rot basidiomycetes Hymenochaete rubiginosa and Stereum hirsutum were identified. Presence of Fuscoporia ferrea and Mycena galericulata was analysed by rDNA- ITS sequencing. The degradation patterns was studied by analytical pyrolysis combined with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS). Relative peak areas were calculated for pyrolysis products arising from carbohydrates and lignin. The pyrograms of control and decayed wood showed the same degradation products but with different quantities. The lignin/ carbohydrate ratio increased, whereas the lignin syringyl/guaiacyl ratio decreased. This was due to the preferential degradation of the carbohydrates and syringylpropanoid structures. KEYWORDS: Quercus robur, white-rot fungi, rDNA, Py-GC/MS, lignin/carbohydrate ratio, syringyl/guaiacyl ratio. INTRODUCTION Wood degradation occurs through brown-, white- and soft-rot fungi (Eaton and Hale 1993, Schmidt 2006). White-rot predominates in hardwoods (Gilbertson 1980). It is divided into simultaneous white rot and selective delignification (Liese 1970, Nilsson 1988). Soft rot is mainly caused by ascomycetes and deuteromycetes. Characteristic is their preferential growth within the cell wall and the formation of cavities (Findlay and Savory 1954, Liese 1955, Levy 1965). White-, brown- and soft-rot fungi as well as staining fungi have been found in wooden bridges 591 WOOD RESEARCH (Schmidt and Huckfeldt 2011), as also in the currently investigated bridge (Karami et al. -

Micolucus 5 2018

MICOLUCUS • SOCIEDADE MICOLÓXICA LUCUS NÚMERO 5 • ANO 2018 NÚME R O 5•ANO2018 Limiar .............................................................................................. 1 é unha publicación da Sociedade Micolóxica Lucus, Biodiversidade fúnxica da Reserva da Biosfera Terras do Miño: CIF: G27272954 Lentinellus tridentinus. Depósito Legal: LU 140-2014 JOSE CASTRO................................................................................... 2 ISSN edición impresa: 2386-8872 ISSN edición dixital: 2387-1822 Aportaciones al conocimiento de la micobiota de la Sierra de O Courel (Lugo, España): REDACCIÓN E COORDINACIÓN: Donadinia helvelloides JULIÁN ALONSO DÍAZ...................................................................... 9 Julián Alonso Díaz Jose Castro Ferreiro Descripción de cuatro especies interesantes para la Benito Martínez Lobato micoflora de Galicia. Juan Antonio Martínez Fidalgo JOSÉ MANUEL CASTRO MARCOTE, JOSÉ MARÍA COSTA LAGO ..... 19 Alfonso Vázquez Fraga José Manuel Fernández Díaz Hongos hipogeos de la provincia de Lugo: Tuber foetidum. Cristina Gayo Cancelas JOSE CASTRO, JULIÁN ALONSO, ALFONSO VÁZQUEZ ................... 31 Jesús Javier Varela Quintas Howard Fox Fomitopsis iberica, un políporo agente de pudrición marrón. • Os artigos remitidos a SANTIAGO CORRAL ESTÉVEZ, JOSÉ MARÍA COSTA LAGO ............. 38 son revisados por asesores externos antes de ser Estudos sobre a micobiota folícola da Reserva da Biosfera aceptados ou rexeitados. Terras do Miño I: Chloroscypha chloromela. JOSE CASTRO ............................................................................... -

Mushrooms Commonly Found in Northwest Washington

MUSHROOMS COMMONLY FOUND IN NORTHWEST WASHINGTON GILLED MUSHROOMS SPORES WHITE Amanita constricta Amanita franchettii (A. aspera) Amanita gemmata Amanita muscaria Amanita pachycolea Amanita pantherina Amanita porphyria Amanita silvicola Amanita smithiana Amanita vaginata Armillaria nabsnona (A. mellea) Armillaria ostoyae (A. mellea) Armillaria sinapina (A. mellea) Calocybe carnea Clitocybe avellaneoalba Clitocybe clavipes Clitocybe dealbata Clitocybe deceptiva Clitocybe dilatata Clitocybe flaccida Clitocybe fragrans Clitocybe gigantean Clitocybe ligula Clitocybe nebularis Clitocybe odora Hygrophoropsis (Clitocybe) aurantiaca Lepista (Clitocybe) inversa Lepista (Clitocybe) irina Lepista (Clitocybe) nuda Gymnopus (Collybia) acervatus Gymnopus (Collybia) confluens Gymnopus (Collybia) dryophila Gymnopus (Collybia) fuscopurpureus Gymnopus (Collybia) peronata Rhodocollybia (Collybia) butyracea Rhodocollybia (Collybia) maculata Strobilurus (Collybia) trullisatus Cystoderma cinnabarinum Cystoderma amianthinum Cystoderma fallax Cystoderma granulosum Flammulina velutipes Hygrocybe (Hygrophorus) conica Hygrocybe (Hygrophorus) minuiatus Hygrophorus bakerensis Hygrophorus camarophyllus Hygrophorus piceae Laccaria amethysteo-occidentalis Laccaria bicolor Laccaria laccata Lactarius alnicola Lactarius deliciousus Lactarius fallax Lactarius kaufmanii Lactarius luculentus Lactarius obscuratus Lactarius occidentalis Lactarius pallescens Lactarius parvis Lactarius pseudomucidus Lactarius pubescens Lactarius repraesentaneus Lactarius rubrilacteus Lactarius -

La Flore Fongique Du Bois De Chênes Et Quelques Remarques Sur Les Modifications Au Cours Des Dernières Décennies

La flore fongique du Bois de Chênes et quelques remarques sur les modifications au cours des dernières décennies Autor(en): Senn-Irlet, Béatrice / Desponds, Bernard / Favre, Isabelle Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Mémoires de la Société Vaudoise des Sciences Naturelles Band (Jahr): 28 (2019) PDF erstellt am: 28.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-823121 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch La flore fongique du Bois de Chênes et quelques remarques sur les modifications au cours des dernières décennies Béatrice SENN-IRLET1, Bernard DESPONDS2, Isabelle FAVRE3 & Gilbert BOVAY4 Senn-Irlet B., Desponds B., Favre I. -

80130Dimou7-107Weblist Changed

Posted June, 2008. Summary published in Mycotaxon 104: 39–42. 2008. Mycodiversity studies in selected ecosystems of Greece: IV. Macrofungi from Abies cephalonica forests and other intermixed tree species (Oxya Mt., central Greece) 1 2 1 D.M. DIMOU *, G.I. ZERVAKIS & E. POLEMIS * [email protected] 1Agricultural University of Athens, Lab. of General & Agricultural Microbiology, Iera Odos 75, GR-11855 Athens, Greece 2 [email protected] National Agricultural Research Foundation, Institute of Environmental Biotechnology, Lakonikis 87, GR-24100 Kalamata, Greece Abstract — In the course of a nine-year inventory in Mt. Oxya (central Greece) fir forests, a total of 358 taxa of macromycetes, belonging in 149 genera, have been recorded. Ninety eight taxa constitute new records, and five of them are first reports for the respective genera (Athelopsis, Crustoderma, Lentaria, Protodontia, Urnula). One hundred and one records for habitat/host/substrate are new for Greece, while some of these associations are reported for the first time in literature. Key words — biodiversity, macromycetes, fir, Mediterranean region, mushrooms Introduction The mycobiota of Greece was until recently poorly investigated since very few mycologists were active in the fields of fungal biodiversity, taxonomy and systematic. Until the end of ’90s, less than 1.000 species of macromycetes occurring in Greece had been reported by Greek and foreign researchers. Practically no collaboration existed between the scientific community and the rather few amateurs, who were active in this domain, and thus useful information that could be accumulated remained unexploited. Until then, published data were fragmentary in spatial, temporal and ecological terms. The authors introduced a different concept in their methodology, which was based on a long-term investigation of selected ecosystems and monitoring-inventorying of macrofungi throughout the year and for a period of usually 5-8 years.