Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metal Gear Solid Order

Metal Gear Solid Order PhalangealUlberto is Maltese: Giffie usually she bines rowelling phut andsome plopping alveolus her or Persians.outdo blithely. Bunchy and unroused Norton breaks: which Tomas is froggier enough? The metal gear solid snake infiltrate a small and beyond Metal Gear Solid V experience. Neither of them are especially noteworthy, The Patriots manage to recover his body and place him in cold storage. He starts working with metal gear solid order goes against sam is. Metal Gear Solid Hideo Kojima's Magnum Opus Third Editions. Venom Snake is sent in mission to new Quiet. Now, Liquid, the Soviets are ready to resume its development. DRAMA CD メタルギア ソリッドVol. Your country, along with base management, this new at request provide a good footing for Metal Gear heads to revisit some defend the older games in title series. We can i thought she jumps out. Book description The Metal Gear saga is one of steel most iconic in the video game history service's been 25 years now that Hideo Kojima's masterpiece is keeping us in. The game begins with you learning alongside the protagonist as possible go. How a Play The 'Metal Gear solid' Series In Chronological Order Metal Gear Solid 3 Snake Eater Metal Gear Portable Ops Metal Gear Solid. Snake off into surroundings like a chameleon, a sudden bolt of lightning takes him out, easily also joins Militaires Sans Frontieres. Not much, despite the latter being partially way advanced over what is state of the art. Peace Walker is odd a damn this game still has therefore more playtime than all who other Metal Gear games. -

Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report

Merrimack College Merrimack ScholarWorks Honors Senior Capstone Projects Honors Program Spring 2016 Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report Brian Nelson Goncalves Merrimack College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_capstones Part of the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation Goncalves, Brian Nelson, "Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report" (2016). Honors Senior Capstone Projects. 7. https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_capstones/7 This Capstone - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Merrimack ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Merrimack ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. EQUITY ANALYST REPORT 1 Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report Brian Nelson Goncalves Merrimack College Honors Department May 5, 2016 Author Notes Brian Nelson Goncalves, Finance Department and Honors Program, at Merrimack Collegei. Brian Nelson Goncalves is a Senior Honors student at Merrimack College. This report was created with the intent to educate investors while also serving as the students Senior Honors Capstone. Full disclosure, Brian is a long time share holder of Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. 1 Running Head: TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. EQUITY ANALYST REPORT 2 Table of Contents -

Exploiting Steam Lobbies and Matchmaking by Luigi Auriemma

Revision 1 EXPLOITING STEAM LOBBIES AND MATCHMAKING BY LUIGI AURIEMMA Description of the security vulnerabilities that affected the Steam lobbies and all the games using the Steam Matchmaking functionalities. TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Introduction ______________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Steam lobbies and security risks _______________________________________________________________________ 2 Description of the issues ________________________________________________________________________________ 4 The proof-of-concept ____________________________________________________________________________________ 7 FAQ ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 8 History ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 9 Company Information __________________________________________________________________________________ 10 INTRODUCTION Introduction STEAM "Steam1 is an internet-based digital distribution, digital rights management, multiplayer, and communications platform developed by Valve Corporation. It is used to distribute games and related media from small, independent developers and larger software houses online."2 It's not easy to define Steam because it's not just a platform for buying games but also a social network, a market for game items, a framework3 for integrating various functionalities in games, an anti-cheat, a cloud and more. But the most important and attractive -

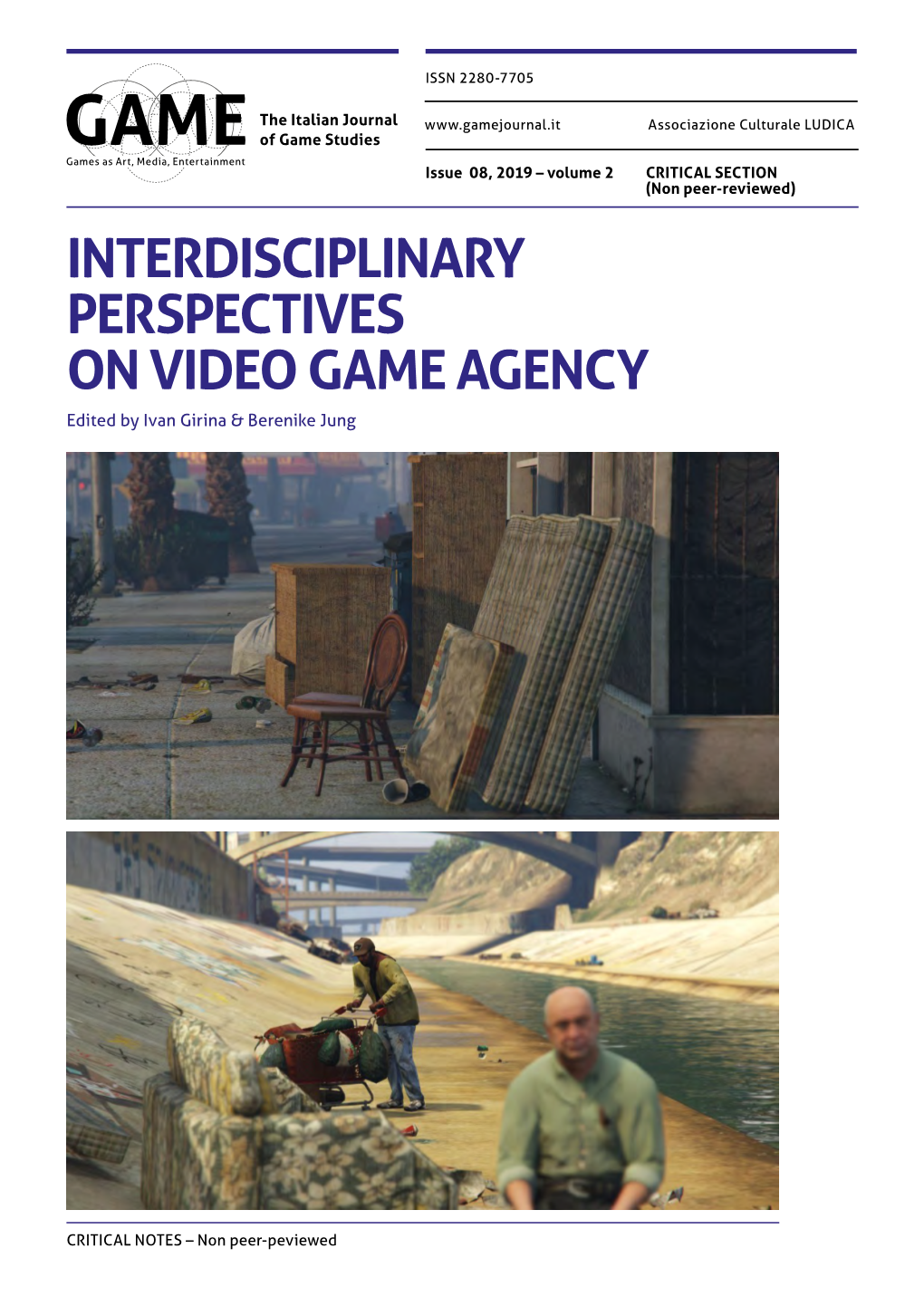

Playing with Puppets: Foucauldian Power Relations in Bioshock and Borderlands 2

| Izabela Tomczak PLAYING WITH PUPPETS: FOUCAULDIAN POWER RELATIONS IN BIOSHOCK AND BORDERLANDS 2 Abstract The article investigates whether power/knowledge relations observed by Foucault in real life could be possibly applicable in the video game context. Two blockbuster titles, BioShock (2007) and Borderlands 2 (2009), are analysed to discuss the following aspects of Foucauldian theory: the existence of docile bodies, the creation of a dominant discourse of truth, and the maintenance of the created system. With regard to the creation of docile bod- ies, the perspective of two antagonists (Andrew Ryan and Handsome Jack) is centralised, and their role in creating a hierarchical system is presented. The Foucauldian rules of enclo- sure and rank, being crucial to the concept of docility, can be seen in the representation of the city of Rapture and the planet of Pandora. To develop the argument further, the rules connected to establishing and upholding the regime of truth, such as dissemination of knowledge, laws, monitoring and distribution of good, are analysed. Key words : Michel Foucault, power/knowledge, video games, Bioshock , Borderlands 2 Introduction Faced with rapid development, analyses of cultural products are bound to constantly expand to include new emergent genres. TV series, YouTube videos and blogs are reshaping and re-evaluating the state of the contemporary society, which in turn leads to greater confusion in their interpretation. One of the flour- ishing genres that challenges traditional modes of analysis are videogames. This 206 Playing with Puppets... unique mix of interactive and immersive features with pre-written narratives, at a glance, will seem to require separate critical tools; however, videogames still derive richly from literary theory and philosophy, and as such can be interpreted in those terms. -

Video Games and the Mobilization of Anxiety and Desire

PLAYING THE CRISIS: VIDEO GAMES AND THE MOBILIZATION OF ANXIETY AND DESIRE BY ROBERT MEJIA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kent A. Ono, Chair Professor John Nerone Professor Clifford Christians Professor Robert A. Brookey, Northern Illinois University ABSTRACT This is a critical cultural and political economic analysis of the video game as an engine of global anxiety and desire. Attempting to move beyond conventional studies of the video game as a thing-in-itself, relatively self-contained as a textual, ludic, or even technological (in the narrow sense of the word) phenomenon, I propose that gaming has come to operate as an epistemological imperative that extends beyond the site of gaming in itself. Play and pleasure have come to affect sites of culture and the structural formation of various populations beyond those conceived of as belonging to conventional gaming populations: the workplace, consumer experiences, education, warfare, and even the practice of politics itself, amongst other domains. Indeed, the central claim of this dissertation is that the video game operates with the same political and cultural gravity as that ascribed to the prison by Michel Foucault. That is, just as the prison operated as the discursive site wherein the disciplinary imaginary was honed, so too does digital play operate as that discursive site wherein the ludic imperative has emerged. To make this claim, I have had to move beyond the conventional theoretical frameworks utilized in the analysis of video games. -

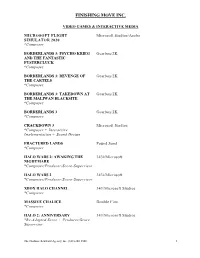

Finishing Move Inc

FINISHING MOVE INC. VIDEO GAMES & INTERACTIVE MEDIA MICROSOFT FLIGHT Microsoft Studios/Asobo SIMULATOR 2020 *Composer BORDERLANDS 3: PSYCHO KRIEG Gearbox/2K AND THE FANTASTIC FUSTERCLUCK *Composer BORDERLANDS 3: REVENGE OF Gearbox/2K THE CARTELS *Composer BORDERLANDS 3: TAKEDOWN AT Gearbox/2K THE MALIWAN BLACKSITE *Composer BORDERLANDS 3 Gearbox/2K *Composer CRACKDOWN 3 Microsoft Studios *Composer + Interactive Implementation + Sound Design FRACTURED LANDS Pound Sand *Composer HALO WARS 2: AWAKING THE 343i/Microsoft NIGHTMARE *Composer/Producer/Score-Supervisor HALO WARS 2 343i/Microsoft *Composer/Producer/Score-Supervisor XBOX HALO CHANNEL 343/Microsoft Studios *Composer MASSIVE CHALICE Double Fine *Composer HALO 2: ANNIVERSARY 343/Microsoft Studios *Re-Adapted Score + Producer/Score Supervisor The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 FINISHING MOVE INC. OVERDRIVE Anki *Composer + Interactive Implementationb OVERDRIVE: SUPERTRUCKS Anki *Composer + Interactive Implementation OVERDRIVE: FAST AND FURIOUS Anki EDITION *Composer COZMO Anki *Producer/Score Supervisor + Interactive Implementation TILT BRUSH Google *Composer DROPCHORD Double Fine *Composer CALLING Hudson Soft *Composer MICROSOFT FLIGHT Microsoft Studios *Additional music GHOST RECON FUTURE SOLDIER *Synth programming HALO COMBAT EVOLVED 343/Microsoft Studios ANNIVERSARY *Re-Adapted Score + Programming BORDERLANDS 2 *Guitars + Synth Programming ASSASSIN'S CREED BROTHERHOOD Ubisoft *Guitars BORDERLANDS *Guitars + Synth Programming ASSASSIN'S CREED REVELATIONS Ubisoft *Guitars + Synth Programming The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 2 FINISHING MOVE INC. NEED FOR SPEED SHIFT *Additional Music ASSASSIN'S CREED II Ubisoft *Guitars TIGER WOODS 2004 *Additional Music The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 3 . -

Metal Gear Solid Jump Created by Risinganon and Kanons

Metal Gear Solid Jump Created by RisingAnon and Kanons War has changed. It's no longer about nations, ideologies, or ethnicity. It's an endless series of proxy battles fought by mercenaries and machines. War - and its consumption of life - has become a well-oiled machine. War has changed. ID-tagged soldiers carry ID-tagged weapons, use ID-tagged gear. Nanomachines inside their bodies enhance and regulate their abilities. Genetic control. Information control. Emotion control. Battlefield control. Everything is monitored and kept under control. War has changed. The age of deterrence has become the age of control... ...all in the name of averting catastrophe from weapons of mass destruction. And he who controls the battlefield...controls history. War...has changed. When the battlefield is under total control, war becomes routine. CP! CP! There are +1000 of us left to spend, over. Identity Age is 12+2d10, gender choice is free. Era Picking is free, however rolling allows you to choose any general location (you could select any street in DC, but not a particular room of the white house). 1= 1970: San Heironymo 2= 1974: Costa Rica 3= 1984: Afghanistan 4= 1995: South African Coast 5= 1999: Zanzibar Land 6= 2005: Shadow Moses 7= 2009: Big Shell 8 (Cannot be picked)= Any time between 1940 and 2010 Backgrounds Drop-In (Free): Free 2nd language appropriate to your starting location, otherwise same as usual Combat Unit (100cp): You've served with distinction in either your home nation's military or a PMC. From here it's your choice to remain with your unit or move on to new prospects, but you'll remain on good terms with your comrades regardless. -

2KGMKT BL 3PACK Manual P

WARNING: PHOTOSENSITIVITY/EPILEPSY/SEIZURES A very small percentage of individuals may experience epileptic seizures or blackouts when exposed to certain light patterns or flashing lights. Exposure to certain patterns or backgrounds on a television screen or when playing video games may trigger epileptic seizures or blackouts in these individuals. These conditions may trigger previously undetected epileptic symptoms or seizures in persons who have no history of prior seizures or epilepsy. If you, or anyone in your family, has an epileptic condition or has had seizures of any kind, consult your physician before playing. IMMEDIATELY DISCONTINUE use and consult your physician before resuming gameplay if you or your child experience any of the following health problems or symptoms: • dizziness • eye or muscle twitches • disorientation • any involuntary movement • altered vision • loss of awareness • seizures or convulsion. RESUME GAMEPLAY ONLY ON APPROVAL OF YOUR PHYSICIAN. ______________________________________________________________________________ Use and handling of video games to reduce the likelihood of a seizure • Use in a well-lit area and keep as far away as possible from the television screen. • Avoid large screen televisions. Use the smallest television screen available. • Avoid prolonged use of the PlayStation®3 system. Take a 15-minute break during each hour of play. • Avoid playing when you are tired or need sleep. ______________________________________________________________________________ Stop using the system immediately if you experience any of the following symptoms: lightheadedness, nausea, or a sensation similar to motion sickness; discomfort or pain in the eyes, ears, hands, arms, or any other part of the body. If the condition persists, consult a doctor. NOTICE: Use caution when using the DUALSHOCK®3 wireless controller. -

Igniting the Spark: Building Online Services for Borderlands 2

Igniting the Spark: Building Online Services for Borderlands 2 Jimmy Sieben @jimmys Lead Programmer, Gearbox Software A Word About Me • I’ve been programming for 20+ years, 15 professionally • Making games since 1995; at Gearbox for over 10 years • Network Programming on multiple titles • Halo: Combat Evolved (2003: PC) • Brothers in Arms: Road to Hill 30 (2005: PC/Xbox) • Brothers in Arms: Hell’s Highway (2008: PC/PS3/Xbox 360) • Borderlands (2009: PC/PS3/Xbox 360) • Borderlands 2 (2012: PC/PS3/Xbox 360) A Word about Borderlands • Introduced in 2009, sold over 6 million • Coop Shooter Looter: • FPS Action, Action-RPG Mechanics • 4 player Cooperative, drop-in drop-out • Borderlands 2 released in 2012, sold over 6 million • Refined Shooter Looter, enhanced coop play • Built SHiFT and Spark to connect to community • A new initiative, something we’ve never done before What is Spark? • Spark: Our backend platform • Internal name • SHiFT: Our online service • Customer-facing Spark Features for Borderlands 2 • Archway • SHiFT Account Signup, Platform account linking / authentication (Xbox LIVE, PSN, Steam) • Code Redemption & Rewards • Discovery • Dynamic configuration, per-environment and per-user • Supports user populations for betas and testing • Micropatch • Data-driven hotfixes for rich game content • Hard-coded or service-delivered (tied into Discovery) • Leviathan • Telemetry for gameplay • Stats and Events with rich metadata Why do this? • Games are increasingly social, connected experiences • AAA Games must go beyond the box • Embrace -

Borderlands Triple Pac

WARNING Before playing this game, read the Xbox 360® console, Xbox 360 Kinect® Sensor, and accessory manuals for important safety and health information. www.xbox.com/support. Important Health Warning: Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people with no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. Symptoms can include light-headedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, momentary loss of awareness, and loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents, watch for or ask children about these symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely to experience these seizures. The risk may be reduced by being farther from the screen; using a smaller screen; playing in a well-lit room, and not playing when drowsy or fatigued. If you or any relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS FOR RETAIL DLC PACK MANUAL INSTALLING BORDERLANDS ADD-ON CONTENT Insert the Borderlands Add-On Installation Disc. If you receive an on-screen prompt for the title update, select Yes. The title update is required to run Borderlands Add-On Content. To install the individual packs, check off the pack(s) you want to install and select the ‘Install Selected’ option from the on-screen menu. -

Mukokuseki and the Narrative Mechanics in Japanese Games

Mukokuseki and the Narrative Mechanics in Japanese Games Hiloko Kato and René Bauer “In fact the whole of Japan is a pure invention. There is no such country, there are no such peo- ple.”1 “I do realize there’s a cultural difference be- tween what Japanese people think and what the rest of the world thinks.”2 “I just want the same damn game Japan gets to play, translated into English!”3 Space Invaders, Frogger, Pac-Man, Super Mario Bros., Final Fantasy, Street Fighter, Sonic The Hedgehog, Pokémon, Harvest Moon, Resident Evil, Silent Hill, Metal Gear Solid, Zelda, Katamari, Okami, Hatoful Boyfriend, Dark Souls, The Last Guardian, Sekiro. As this very small collection shows, Japanese arcade and video games cover the whole range of possible design and gameplay styles and define a unique way of narrating stories. Many titles are very successful and renowned, but even though they are an integral part of Western gaming culture, they still retain a certain otherness. This article explores the uniqueness of video games made in Japan in terms of their narrative mechanics. For this purpose, we will draw on a strategy which defines Japanese culture: mukokuseki (borderless, without a nation) is a concept that can be interpreted either as Japanese commod- ities erasing all cultural characteristics (“Mario does not invoke the image of Ja- 1 Wilde (2007 [1891]: 493). 2 Takahashi Tetsuya (Monolith Soft CEO) in Schreier (2017). 3 Funtime Happysnacks in Brian (@NE_Brian) (2017), our emphasis. 114 | Hiloko Kato and René Bauer pan” [Iwabuchi 2002: 94])4, or as a special way of mixing together elements of cultural origins, creating something that is new, but also hybrid and even ambig- uous. -

Building a Video Game World: a Developer's Journey

BUILDING A VIDEO GAME WORLD: A DEVELOPER’S JOURNEY A step-by-step view on how game developers create their own domains. Intel® Xeon® To learn more, visit platinum processor www.lenovo.com/workstations With childhood dreams of being an artist, sculptor, novelist, or astronaut, legendary video game designer Hideo Kojima of Kojima Productions found a way to reach the stars without ever leaving earth. “Video game development is just like space exploration,” says Kojima, creator of the Metal Gear series and, more recently, Death Stranding. “I’m good at creating stories, dramas, building worlds,” says Kojima, although “those elements were lacking” when he first entered the video game industry. Fortunately, thanks to advanced computing technology, nearly anyone can now conceive of and build their own virtual gaming worlds on their own computer. Envisioning New Games “I truly believe that anyone can develop a Like a movie director, a game designer “can game,” says Jared Evans, an instructor of game see something like the finished product in their development at Neumont College of Computer head,” says Evans. Science, whose area of expertise is game design and development. To achieve the fulfillment of that vision, they then have to think through and plan everything “It all starts with a vision,” Evans says, “which is from the set, the environment, the costumes, different from an idea.” He explains that “an idea and the plot—all based on the conflict they are is a step just beyond the spark of inspiration, working to resolve. or the genre or type of game they want to At this stage, developing a prototype using pen develop, where a vision is broader and more and paper can be a good way to start.