Identity Creation and World-Building Through Discourse in Video Game Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report

Merrimack College Merrimack ScholarWorks Honors Senior Capstone Projects Honors Program Spring 2016 Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report Brian Nelson Goncalves Merrimack College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_capstones Part of the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation Goncalves, Brian Nelson, "Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report" (2016). Honors Senior Capstone Projects. 7. https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_capstones/7 This Capstone - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Merrimack ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Merrimack ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. EQUITY ANALYST REPORT 1 Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report Brian Nelson Goncalves Merrimack College Honors Department May 5, 2016 Author Notes Brian Nelson Goncalves, Finance Department and Honors Program, at Merrimack Collegei. Brian Nelson Goncalves is a Senior Honors student at Merrimack College. This report was created with the intent to educate investors while also serving as the students Senior Honors Capstone. Full disclosure, Brian is a long time share holder of Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. 1 Running Head: TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. EQUITY ANALYST REPORT 2 Table of Contents -

Chell Game: Representation, Identification, and Racial Ambiguity in PORTAL and PORTAL 2 2015

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Jennifer deWinter; Carly A. Kocurek Chell Game: Representation, Identification, and Racial Ambiguity in PORTAL and PORTAL 2 2015 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14996 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: deWinter, Jennifer; Kocurek, Carly A.: Chell Game: Representation, Identification, and Racial Ambiguity in PORTAL and PORTAL 2. In: Thomas Hensel, Britta Neitzel, Rolf F. Nohr (Hg.): »The cake is a lie!« Polyperspektivische Betrachtungen des Computerspiels am Beispiel von PORTAL. Münster: LIT 2015, S. 31– 48. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14996. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://nuetzliche-bilder.de/bilder/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Hensel_Neitzel_Nohr_Portal_Onlienausgabe.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Weitergabe unter Attribution - Non Commercial - Share Alike 3.0/ License. For more gleichen Bedingungen 3.0/ Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere information see: Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Jennifer deWinter / Carly A. Kocurek Chell Game: Representation, Identification, and Racial Ambiguity in ›Portal‹ and ›Portal 2‹ Chell stands in a corner facing a portal, then takes aim at the adjacent wall with the Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device. Between the two portals, one ringed in blue, one ringed in orange, Chell is revealed, reflected in both. And, so, we, the player, see Chell. She is a young woman with a ponytail, wearing an orange jumpsuit pulled down to her waist and an Aperture Science-branded white tank top. -

Exploring the Experiences of Gamers Playing As Multiple First-Person Video Game Protagonists in Halo 3: ODST’S Single-Player Narrative

Exploring the experiences of gamers playing as multiple first-person video game protagonists in Halo 3: ODST’s single-player narrative Richard Alexander Meyers Bachelor of Arts Submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) School of Creative Practice Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2018 Keywords First-Person Shooter (FPS), Halo 3: ODST, Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), ludus, paidia, phenomenology, video games. i Abstract This thesis explores the experiences of gamers playing as multiple first-person video game protagonists in Halo 3: ODST, with a view to formulating an understanding of player experience for the benefit of video game theorists and industry developers. A significant number of contemporary console-based video games are coming to be characterised by multiple playable characters within a game’s narrative. The experience of playing as more than one video game character in a single narrative has been identified as an under-explored area in the academic literature to date. An empirical research study was conducted to explore the experiences of a small group of gamers playing through Halo 3: ODST’s single-player narrative. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was used as a methodology particularly suited to exploring a new or unexplored area of research and one which provides a nuanced understanding of a small number of people experiencing a phenomenon such as, in this case, playing a video game. Data were gathered from three participants through experience journals and subsequently through two semi- structured interviews. The findings in relation to participants’ experiences of Halo 3: ODST’s narrative were able to be categorised into three interrelated narrative elements: visual imagery and world-building, sound and music, and character. -

Using Game Design and Game Elements in the EFL Classroom ======

>GAMIFICATION ========================================================== >Using game design and game elements in the EFL classroom_ ========================================================== Figure 1 Alien by Illaria Bernareggi / The Noun Project Gilles Glod professeur-candidat Lycée Technique de Bonnevoie Declaration of originality I certify that all material contained in this travail de candidature is my own work. All source material is clearly acknowledged as and when it occurs in the references, as well as in the list of works cited. Luxembourg, 4th November 2017 2 Gilles Glod professeur-candidat au Lycée Technique de Bonnevoie Gamification: using game design and game elements in the EFL classroom Bonnevoie, 2017 3 Abstract Research objectives This thesis discusses the ways in which one of the basic human instincts – the urge to play – can be used in an EFL classroom to improve learners’ motivation, social skills and willingness to engage in language learning. My thesis focuses on three major aspects. First, in my lessons, I have implemented games as well as features that often form the core of games, such as rules of play, experience points, achievements, and the levelling up and customization of an avatar. The learners see their progress mirrored within the paradigm of role-playing games: their activities in the classroom inform the de- velopment of their in-game avatars and unlock real-life abilities and rewards. Second, I analyse which games and aspects of gamification are conducive to the creation of a ludic space. While the use of tablets is not the core focus of this thesis, I have worked with pedagogical and language-learning games designed for tablets as well as classroom games designed to use tablets as one of their central features. -

DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CHANGEFUL TALES: DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Aaron A. Reed June 2017 The Dissertation of Aaron A. Reed is approved: Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Chair Michael Mateas Michael Chemers Dean Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Aaron A. Reed 2017 Table of Contents List of Figures viii List of Tables xii Abstract xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1 Framework 15 1.1 Vocabulary . 15 1.1.1 Foundational terms . 15 1.1.2 Storygames . 18 1.1.2.1 Adventure as prototypical storygame . 19 1.1.2.2 What Isn't a Storygame? . 21 1.1.3 Expressive Input . 24 1.1.4 Why Fiction? . 27 1.2 A Framework for Storygame Discussion . 30 1.2.1 The Slipperiness of Genre . 30 1.2.2 Inputs, Events, and Actions . 31 1.2.3 Mechanics and Dynamics . 32 1.2.4 Operational Logics . 33 1.2.5 Narrative Mechanics . 34 1.2.6 Narrative Logics . 36 1.2.7 The Choice Graph: A Standard Narrative Logic . 38 2 The Adventure Game: An Existing Storygame Mode 44 2.1 Definition . 46 2.2 Eureka Stories . 56 2.3 The Adventure Triangle and its Flaws . 60 2.3.1 Instability . 65 iii 2.4 Blue Lacuna ................................. 66 2.5 Three Design Solutions . 69 2.5.1 The Witness ............................. 70 2.5.2 Firewatch ............................... 78 2.5.3 Her Story ............................... 86 2.6 A Technological Fix? . -

Exploiting Steam Lobbies and Matchmaking by Luigi Auriemma

Revision 1 EXPLOITING STEAM LOBBIES AND MATCHMAKING BY LUIGI AURIEMMA Description of the security vulnerabilities that affected the Steam lobbies and all the games using the Steam Matchmaking functionalities. TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Introduction ______________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Steam lobbies and security risks _______________________________________________________________________ 2 Description of the issues ________________________________________________________________________________ 4 The proof-of-concept ____________________________________________________________________________________ 7 FAQ ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 8 History ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 9 Company Information __________________________________________________________________________________ 10 INTRODUCTION Introduction STEAM "Steam1 is an internet-based digital distribution, digital rights management, multiplayer, and communications platform developed by Valve Corporation. It is used to distribute games and related media from small, independent developers and larger software houses online."2 It's not easy to define Steam because it's not just a platform for buying games but also a social network, a market for game items, a framework3 for integrating various functionalities in games, an anti-cheat, a cloud and more. But the most important and attractive -

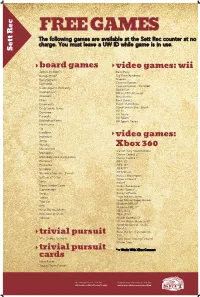

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Game Enforcer Is Just a Group of People Providing You with Information and Telling You About the Latest Games

magazine you will see the coolest ads and Letter from The the most legit info articles you can ever find. Some of the ads include Xbox 360 skins Editor allowing you to customize your precious baby. Another ad is that there is an amazing Ever since I decided to do a magazine I ad on Assassins Creed Brotherhood and an already had an idea in my head and that idea amazing ad on Clash Of Clans. There is is video games. I always loved video games articles on a strategy game called Sid Meiers it gives me something to do it entertains me Civilization 5. My reason for this magazine and it allows me to think and focus on that is to give you fans of this magazine a chance only. Nowadays the best games are the ones to learn more about video games than any online ad can tell you and also its to give you a chance to see the new games coming out or what is starting to be making. Game Enforcer is just a group of people providing you with information and telling you about the latest games. We have great ads that we think you will enjoy and we hope you enjoy them so much you buy them and have fun like so many before. A lot of the games we with the best graphics and action. Everyone likes video games so I thought it would be good to make a magazine on video games. Every person who enjoys video games I expect to buy it and that is my goal get the most sales and the best ratings than any other video game magazine. -

View the Manual

White Pearl Game Mechanics Manual & Full Credits Game Manual & Credits © Harry Gill White Pearl Game Mechanics Manual & Full Credits Use This manual will explain all the main mechanics of the game. For the complete official guide, which contains a story and boss walkthrough (including much more, such as the inclusion of the game’s entire database); please install the Chronicle Edition DLC. Important Terminology Action Button – Refers to the button used to interact with objects and NPCs, as well as confirm selections. Used by pressing Enter/X/Square. Cancel Button – Refers to the button used to cancel selections and sometimes access menus. Used by pressing ESC/B/Circle © Harry Gill White Pearl Game Mechanics Manual & Full Credits Developer Comments It’s been a long time since White Pearl’s launch, after which I have been working tirelessly to update the game, bug fix it, add additional content, while developing my second game Fabrication – which is set to release at the end of 2020. White Pearl is my first ever game project, and admittedly over-ambitious, wouldn’t you agree? While I think the reviews do a good enough job of explains the positives and negatives of the game, sometimes I look back on the game and think “I wish I did this!”. But game development is very difficult. You must work in a certain amount of time and restrictions to get anything done, which is why this game exists in the first place. If I kept asking myself questions and trying to change things here and there, this game would have never been released. -

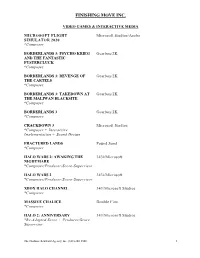

Finishing Move Inc

FINISHING MOVE INC. VIDEO GAMES & INTERACTIVE MEDIA MICROSOFT FLIGHT Microsoft Studios/Asobo SIMULATOR 2020 *Composer BORDERLANDS 3: PSYCHO KRIEG Gearbox/2K AND THE FANTASTIC FUSTERCLUCK *Composer BORDERLANDS 3: REVENGE OF Gearbox/2K THE CARTELS *Composer BORDERLANDS 3: TAKEDOWN AT Gearbox/2K THE MALIWAN BLACKSITE *Composer BORDERLANDS 3 Gearbox/2K *Composer CRACKDOWN 3 Microsoft Studios *Composer + Interactive Implementation + Sound Design FRACTURED LANDS Pound Sand *Composer HALO WARS 2: AWAKING THE 343i/Microsoft NIGHTMARE *Composer/Producer/Score-Supervisor HALO WARS 2 343i/Microsoft *Composer/Producer/Score-Supervisor XBOX HALO CHANNEL 343/Microsoft Studios *Composer MASSIVE CHALICE Double Fine *Composer HALO 2: ANNIVERSARY 343/Microsoft Studios *Re-Adapted Score + Producer/Score Supervisor The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 FINISHING MOVE INC. OVERDRIVE Anki *Composer + Interactive Implementationb OVERDRIVE: SUPERTRUCKS Anki *Composer + Interactive Implementation OVERDRIVE: FAST AND FURIOUS Anki EDITION *Composer COZMO Anki *Producer/Score Supervisor + Interactive Implementation TILT BRUSH Google *Composer DROPCHORD Double Fine *Composer CALLING Hudson Soft *Composer MICROSOFT FLIGHT Microsoft Studios *Additional music GHOST RECON FUTURE SOLDIER *Synth programming HALO COMBAT EVOLVED 343/Microsoft Studios ANNIVERSARY *Re-Adapted Score + Programming BORDERLANDS 2 *Guitars + Synth Programming ASSASSIN'S CREED BROTHERHOOD Ubisoft *Guitars BORDERLANDS *Guitars + Synth Programming ASSASSIN'S CREED REVELATIONS Ubisoft *Guitars + Synth Programming The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 2 FINISHING MOVE INC. NEED FOR SPEED SHIFT *Additional Music ASSASSIN'S CREED II Ubisoft *Guitars TIGER WOODS 2004 *Additional Music The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 3 . -

WITH OUR DEMONS a Thesis Submitted By

1 MONSTROSITIES MADE IN THE INTERFACE: THE IDEOLOGICAL RAMIFICATIONS OF ‘PLAYING’ WITH OUR DEMONS A Thesis submitted by Jesse J Warren, BLM Student ID: u1060927 For the award of Master of Arts (Humanities and Communication) 2020 Thesis Certification Page This thesis is entirely the work of Jesse Warren except where otherwise acknowledged. This work is original and has not previously been submitted for any other award, except where acknowledged. Signed by the candidate: __________________________________________________________________ Principal Supervisor: _________________________________________________________________ Abstract Using procedural rhetoric to critique the role of the monster in survival horror video games, this dissertation will discuss the potential for such monsters to embody ideological antagonism in the ‘game’ world which is symptomatic of the desire to simulate the ideological antagonism existing in the ‘real’ world. Survival video games explore ideology by offering a space in which to fantasise about society's fears and desires in which the sum of all fears and object of greatest desire (the monster) is so terrifying as it embodies everything 'other' than acceptable, enculturated social and political behaviour. Video games rely on ideology to create believable game worlds as well as simulate believable behaviours, and in the case of survival horror video games, to simulate fear. This dissertation will critique how the games Alien:Isolation, Until Dawn, and The Walking Dead Season 1 construct and themselves critique representations of the ‘real’ world, specifically the way these games position the player to see the monster as an embodiment of everything wrong and evil in life - everything 'other' than an ideal, peaceful existence, and challenge the player to recognise that the very actions required to combat or survive this force potentially serve as both extensions of existing cultural ideology and harbingers of ideological resistance across two worlds – the ‘real’ and the ‘game’. -

Game Manual Introduction

GAME MANUAL INTRODUCTION CREATE YOUR CHARACTER ATTRIBUTES SKILLS TRAITS PERSONALITY, HEREDITARY POINTS AND BACKGROUND OPTIONAL MODES LEVEL UP DECK OF DOOM EXPLORING THE WORLD MOVEMENTS MENU AND COMMANDS SAVE AND LOAD YOUR GAME COLLECT FOOD, WATER AND REST WHEN YOU CAN RESOURCES WEAPONS AND ARMOURS SPECIAL ITEMS MIX AND CRAFT CAMPING AND RESTING HUNTING PITS, TRAPS AND SECRETS THE SHELTER EVENTS AND SPECIAL OBJECTS ENEMIES COMBAT COMMANDS AND INTERFACE IN BATTLE STAMINA, EQUIPMENT AND ROUND ORDER CARNAGE ENEMIES SPECIAL ATTACKS MAGIC HOW TO CAST A SPELL EMPOWER A SPELL MAGIC MAP 2 RUNES SUMMON A CREATURE BASIC SPELLBOOK HINTS AND TIPS CREDITS 3 INTRODUCTION In the last few centuries the world population has rapidly fallen. No one knows how many human beings currently live on Earth, but it is assumed that they are less than 100,000. The end of the human race isn't coming because of nuclear wars, pandemics or natural disasters… ...but because Hell has come to Earth. At the end of the 20th century, thousands of demons began to invade our world. The Earth quickly became their hunting ground and the human civilization is now almost completely erased. Few humans survived. You are one of them. 4 CREATE YOUR CHARACTER You can freely create your character choosing how to distribute Stat Points and Skill Points, selecting his Personality and his Background. If you prefer, you can choose an Archetype to automatically set Attributes and Skills; or, you can randomly generate a character and obtain +3 Stat Points. ATTRIBUTES Attributes are the basic stats of your character: ● STRENGTH +5% Melee DMG, +50 Max STAMINA, +35 Max Carry per point.