WITH OUR DEMONS a Thesis Submitted By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Westminsterresearch the Artist Biopic

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch The artist biopic: a historical analysis of narrative cinema, 1934- 2010 Bovey, D. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr David Bovey, 2015. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 1 THE ARTIST BIOPIC: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF NARRATIVE CINEMA, 1934-2010 DAVID ALLAN BOVEY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Master of Philosophy December 2015 2 ABSTRACT The thesis provides an historical overview of the artist biopic that has emerged as a distinct sub-genre of the biopic as a whole, totalling some ninety films from Europe and America alone since the first talking artist biopic in 1934. Their making usually reflects a determination on the part of the director or star to see the artist as an alter-ego. Many of them were adaptations of successful literary works, which tempted financial backers by having a ready-made audience based on a pre-established reputation. The sub-genre’s development is explored via the grouping of films with associated themes and the use of case studies. -

Brief for Petitioners

No. 20-315 In the Supreme Court of the United States JOSE SANTOS SANCHEZ AND SONIA GONZALEZ, PETITIONERS, v. ALEJANDRO N. MAYORKAS, SECRETARY, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, ET AL., RESPONDENTS. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS LISA S. BLATT JAIME W. APARISI AMY MASON SAHARIA Counsel of Record A. JOSHUA PODOLL YUSUF R. AHMAD MICHAEL J. MESTITZ DANIELA RAAYMAKERS ALEXANDER GAZIKAS APARISI LAW DANIELLE J. SOCHACZEVSKI 819 Silver Spring Avenue WILLIAMS & CONNOLLY LLP Silver Spring, MD 20910 725 Twelfth Street, N.W. (301) 562-1416 Washington, DC 20005 [email protected] (202) 434-5000 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether, under 8 U.S.C. § 1254a(f)(4), a grant of Temporary Protected Status authorizes eligible nonciti- zens to obtain lawful-permanent-resident status under 8 U.S.C. § 1255. (I) II PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS Petitioners are Jose Santos Sanchez and Sonia Gon- zalez. Respondents are Alejandro N. Mayorkas, Secre- tary, United States Department of Homeland Security; Director, United States Citizenship & Immigration Ser- vices; Director, United States Citizenship & Immigration Services Nebraska Service Center; and District Director, United States Citizenship & Immigration Services New- ark. III TABLE OF CONTENTS Page OPINIONS BELOW ........................................................... 1 JURISDICTION ................................................................. 2 STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED ..................... 2 STATEMENT ..................................................................... -

Magisterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MAGISTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Magisterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „Player Characters in Plattform-exklusiven Videospielen“ verfasst von / submitted by Christof Strauss Bakk.phil. BA BA MA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2019 / Vienna 2019 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / UA 066 841 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Magisterstudium Publizistik- und degree programme as it appears on Kommunikationswissenschaft the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: tit. Univ. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Duchkowitsch 1. Einleitung ....................................................................................................................... 1 2. Was ist ein Videospiel .................................................................................................... 2 3. Videospiele in der Kommunikationswissenschaft............................................................ 3 4. Methodik ........................................................................................................................ 7 5. Videospiel-Genres .........................................................................................................10 6. Geschichte der Videospiele ...........................................................................................13 6.1. Die Anfänge der Videospiele ..................................................................................13 -

Review: 'Until Dawn' Adds Clever Twists to Teen Horror Genre 25 August 2015, Bylou Kesten

Review: 'Until Dawn' adds clever twists to teen horror genre 25 August 2015, byLou Kesten those hoary genre tropes, then throws in a bunch more to keep you off balance. There's a creepy psychiatrist. There's an ancient Native American curse. There's an abandoned sanitarium, and a 50-year-old tragedy that may explain all the mayhem. Don't get too comfortable once you think you've pegged the psycho killer, because there are still many hours to go before sun-up. "Until Dawn" benefits from a game, appealing young cast, led by Hayden Panettiere of "Nashville" and Rami Malek of "Mr. Robot." Peter Stormare—from "Fargo" and too many other movies to list—also shows up to deliver his special brand of This image released by Sony Computer Entertainment sublime creepiness. America LLC shows an image of Hayden Panettiere, who voices the character of Samantha, in a scene from the video game, "Until Dawn." (Sony Computer Entertainment America LLC via AP) Years of horror movies have taught us the proper response to an invitation to spend a weekend at a cabin in the woods: No thanks. If anyone followed that advice, we wouldn't have "Friday the 13th," ''The Evil Dead" or, well, "The Cabin in the Woods." But the kids in "Until Dawn" (Sony, for the PlayStation 4, $59.95) have even more reason to stay home: The last time they went, two of their friends vanished. A year later, eight teenagers decide to return to the site to try and get some closure on the tragedy. -

“A Jill Sandwich”. Gender Representation in Zombie Videogames

“A Jill Sandwich”. Gender Representation in Zombie Videogames. Esther MacCallum-Stewart From Resident Evil (Capcom 1996 - present) to The Walking Dead (Telltale Games 2012-4), women are represented in zombie games in ways that appear to refigure them as heroines in their own right, a role that has traditionally been represented as atypical in gaming genres. These women are seen as pioneering – Jill Valentine is often described as one of the first playable female protagonists in videogaming, whilst Clementine and Ellie from The Walking Dead and The Last of Us (Naughty Dog 2013) are respectively, a young child and a teenager undergoing coming of age rites of passage in the wake of a zombie apocalypse. Accompanying them are male protagonists who either compliment these roles, or alternatively provide useful explorations of masculinity in games that move beyond gender stereotyping. At first, these characters appear to disrupt traditional readings of gender in the zombie genre, avoiding the stereotypical roles of final girl, macho hero or princess in need of rescuing. Jill Valentine, Claire Redfield and Ada Wong of the Resident Evil series are resilient characters who often have independent storyarcs within the series, and possess unique ludic attributes that make them viable choices for the player (for example, a greater amount of inventory). Their physical appearance - most usually dressed in combat attire - additionally means that they partially avoid critiques of pandering to the male gaze, a visual trope which dominates female representation in gaming. Ellie and Clementine introduce the player to non-sexualised portrayals of women who ultimately emerge as survivors and protagonists, and further episodes of each game jettison their male counterparts to focus on each of these young adult’s development. -

PT, Freud, and Psychological Horror

Press Start Silent Halls Silent Halls: P.T., Freud, and Psychological Horror Anna Maria Kalinowski York University, Toronto Abstract “What is a ghost?” “An emotion, a terrible moment condemned to repeat itself over and over…” —The Devil’s Backbone (Del Toro, 2001) This paper analyses P.T. (Kojima Productions, 2014), a playable teaser made to demo a planned instalment within the Silent Hill franchise. While the game is now indefinitely cancelled, P.T. has cemented itself not only as a full gaming experience, but also as a juggernaut in the genre of psychological horror. Drawing from Sigmund Freud’s concept of the uncanny, the aim of the paper is to address how these psychological concepts surface within the now infamous never-ending hallway of P.T. and create a deeply psychologically horrifying experience. Keywords psychological horror; the uncanny; Freud; game design; Press Start 2019 | Volume 5 | Issue 1 ISSN: 2055-8198 URL: http://press-start.gla.ac.uk Press Start is an open access student journal that publishes the best undergraduate and postgraduate research, essays and dissertations from across the multidisciplinary subject of game studies. Press Start is published by HATII at the University of Glasgow. Kalinowski Silent Halls Introduction The genre of psychological horror is a complex one to navigate through with ease, especially for those that are faint of heart. Despite its contemporary popularity, when the sub-genre first began to emerge within horror films, it was considered to be a detriment to the horror genre (Jancovich, 2010, p. 47). The term ‘psychological’ was often used to disguise the taming of horror elements instead of pushing the genre into more terrifying territories. -

On Videogames: Representing Narrative in an Interactive Medium

September, 2015 On Videogames: Representing Narrative in an Interactive Medium. 'This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy' Dawn Catherine Hazel Stobbart, Ba (Hons) MA Dawn Stobbart 1 Plagiarism Statement This project was written by me and in my own words, except for quotations from published and unpublished sources which are clearly indicated and acknowledged as such. I am conscious that the incorporation of material from other works or a paraphrase of such material without acknowledgement will be treated as plagiarism, subject to the custom and usage of the subject, according to the University Regulations on Conduct of Examinations. (Name) Dawn Catherine Stobbart (Signature) Dawn Stobbart 2 This thesis is formatted using the Chicago referencing system. Where possible I have collected screenshots from videogames as part of my primary playing experience, and all images should be attributed to the game designers and publishers. Dawn Stobbart 3 Acknowledgements There are a number of people who have been instrumental in the production of this thesis, and without whom I would not have made it to the end. Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Kamilla Elliott, for her continuous and unwavering support of my Ph.D study and related research, for her patience, motivation, and commitment. Her guidance helped me throughout all the time I have been researching and writing of this thesis. When I have faltered, she has been steadfast in my ability. I could not have imagined a better advisor and mentor. I would not be working in English if it were not for the support of my Secondary school teacher Mrs Lishman, who gave me a love of the written word. -

Women in Film Time: Forty Years of the Alien Series (1979–2019)

IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 6 – Issue 2 – Autumn 2019 Women in Film Time: Forty Years of the Alien Series (1979–2019) Susan George, University of Delhi, India. Abstract Cultural theorists have had much to read into the Alien science fiction film series, with assessments that commonly focus on a central female ‘heroine,’ cast in narratives that hinge on themes of motherhood, female monstrosity, birth/death metaphors, empire, colony, capitalism, and so on. The films’ overarching concerns with the paradoxes of nature, culture, body and external materiality, lead us to concur with Stephen Mulhall’s conclusion that these concerns revolve around the issue of “the relation of human identity to embodiment”. This paper uses these cultural readings as an entry point for a tangential study of the Alien films centring on the subject of time. Spanning the entire series of four original films and two recent prequels, this essay questions whether the Alien series makes that cerebral effort to investigate the operations of “the feminine” through the space of horror/adventure/science fiction, and whether the films also produce any deliberate comment on either the lived experience of women’s time in these genres, or of film time in these genres as perceived by the female viewer. Keywords: Alien, SF, time, feminine, film 59 IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 6 – Issue 2 – Autumn 2019 Alien Films that Philosophise Ridley Scott’s 1979 S/F-horror film Alien spawned not only a remarkable forty-year cinema obsession that has resulted in six specific franchise sequels and prequels till date, but also a considerable amount of scholarly interest around the series. -

A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post-Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism" (2019)

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2019 A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post- Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism Brent Linsley University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Linsley, Brent, "A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post-Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 3341. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3341 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post-Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Brent Linsley Henderson State University Bachelor of Arts in English, 2000 Henderson State University Master of Liberal Arts in English, 2005 August 2019 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _____________________________________ M. Keith Booker, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________________ ______________________________________ Robert Cochran, Ph.D. Susan Marren, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member Abstract From Frank Kermode to Norman Cohn to John Hall, scholars agree that apocalypse historically has represented times of radical change to social and political systems as older orders are wiped away and replaced by a realignment of respective norms. This paradigm is predicated upon an understanding of apocalypse that emphasizes the rebuilding of communities after catastrophe has occurred. -

Battleswithbitsofrubber.Com Page 1 CONTENTS

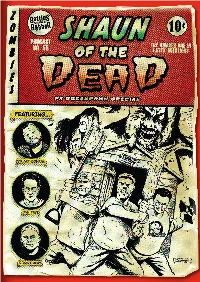

battleswithbitsofrubber.com Page 1 CONTENTS Credits and thanks....................................................................................... Page 3 Foreword by Joe Nazzaro ........................................................................... Page 4 Introduction ................................................................................................. Page 5 Effects in chronological order 1. ‘Haven’t you had your tea?’ ................................................................... Page 6 2. ‘In the garden ... there’s a girl’................................................................ Page 7 3. ‘He’s got an arm off...’ ............................................................................. Page 9 4. ‘Which one do you want? Girl or bloke?’ ........................................... Page 11 5. ‘We take care of Philip.’ .......................................................................... Page 13 6. ‘We’re gonna borrow your car, okay...’ ................................................ Page 13 7. ‘I guess we’ll have to take the Jag.’ ...................................................... Page 14 8. ‘I’ll just flip the mains breakers...’ ........................................................ Page 15 9. ‘I didn’t want to say anything.’.............................................................. Page 16 10. ‘Cock it!’.................................................................................................. Page 17 11. ‘I’m sorry Mum.’ ..................................................................................... -

Histórias De Aprendizagem Da Língua Inglesa Através De Videogames

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE ALAGOAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS E LINGUÍSTICA RITACIRO CAVALCANTE DA SILVA Histórias de Aprendizagem da Língua Inglesa Através de Videogames: Uma Experiência em Pesquisa Narrativa Maceió 2015 RITACIRO CAVALCANTE DA SILVA Histórias de Aprendizagem da Língua Inglesa Através de Videogames: Uma Experiência em Pesquisa Narrativa Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em Letras e Linguística da Universidade Federal de Alagoas para obtenção do título de Mestre em Letras e Linguística. Área de Concentração: Linguística Aplicada Orientador: Prof. Dr. Sérgio Ifa Maceió 2015 Catalogação na fonte Universidade Federal de Alagoas Biblioteca Central Divisão de Tratamento Técnico Bibliotecário Responsável: Valter dos Santos Andrade S586h Silva, Ritaciro Cavalcante da. Histórias de aprendizagem da língua inglesa através de videogames : Uma experiência em pesquisa narrativa / Ritaciro Cavalcante da Silva. – Maceió, 2015. 238 f.: il. Orientador: Sérgio Ifa. Dissertação (Mestrado em Linguística) – Universidade Federal de Alagoas. Faculdade de Letras. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras e Linguística. Maceió, 2015. Bibliografia: f. 138-150. 1. Língua inglesa – Estudo e ensino. 2. Ensino de língua – Meio auxiliares. 3. Vídeo game - Utilização. 4. Pesquisa narrativa. I. Título. CDU: 811.111 AGRADECIMENTOS A Deus, se ele estiver mesmo por aí. A meu orientador, o Prof. Dr. Sérgio Ifa, por me apoiar desde a graduação, e por toda a confiança depositada no mestrado, desde o acolhimento de um projeto com tema incomum na academia, até os últimos instantes. Aos professores e técnicos-administrativos do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras e Linguística (PPGLL) da UFAL, por todos os conselhos, ensinamentos e discussões. À Fundação de Amparo de Pesquisa do Estado de Alagoas, não apenas pelo financiamento concedido através de bolsa de mestrado (Processo 60030 271/2013), mas por todo o apoio, paciência, e companheirismo que tive durante meu tempo como técnico em informática naquela instituição.