How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abia State No

ABIA STATE NO. NAME STATUS ADDRESS 1 ABIA FIRST II DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 140 UMULE RD. BY UKWUAKPU OSISIOMA ABA. 2 AJAE DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 53 AWOLOWO SGBY UMUWAYA ROAD UMUAHIA 3 BASIC DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED OPPOSITE VISION AFRICA RADIO UMUAHIA 4 BENSON DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED UBAKALA STREET BY CO-OPERATIVE UMUAHIA 5 BOBOS DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO. 105 ABA OWEERI ROAD, ABIA STATE 6 CAREFUL DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED 111/113 AZIKWE ROAD ABA 7 CHIBEST DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 7 INDUSTRIAL LAYOUT OSISIOMA NGWA LOCAL GOVT AREA 8 CHIBEST DRIVING SCHOOL UMUAHIA APPROVED 34A POWA SHOPPING PLAZA UMUAHIA, NORTH LGA, ABIA STATE 9 CHINEDUM PRIVATE DRIVING APPROVED NO 2 AZIKWE OCHENDU CLOSE 10 DIAMOND HEART INTERNATIONAL APPROVED NO.10 BCA ROAD UMUAHIA DRIVING SCHOOL 11 DIVINE DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED AHIAEKE NDUME IBEKU OFF UMUSIKE ROAD UMUAHIA 12 DRIVE-WELL SCHOOL OF MOTORING, APPROVED 27 BRASS ST. ABA ABIA STATE. 13 ENG AMOSON DRIVING SCH APPROVED 95 FGC ROAD EBEM OHAFIA 14 EXPERTS DRIVING SCH APPROVED 133 IKOT- EKPENE ROAD OGBORHILL ABA, ABA NORTH LGA, ABIA STATE. 15 FLUX DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED OPPOSITE VISION AFRICA F.M RADIO ALONG SECRETARIAT ROAD, OGURUBE LAYOUT UMUAHIA 16 GIVENCHY DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 60 WARRI BY BENDER ROAD UMUAHIA, ABIA STATE. 17 HALLMARK DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED SUITE 4, 44-55 OSINULO SHOPPING COMPLEX ISI COURT UMUOBIA OLOKORO, UMUAHIA, ABIA STATE 18 IFEANYI DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED AMAWOM OBORO IKWUANO LGA 19 IJEOMA DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO.3 CHECHE CLOSE AMANGWU, OHAFIA, ABIA STATE 20 INTERNATIONAL DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO. 2 MECHANIC LAYOUT OFF CLUB ROAD UMUAHIA. -

Ph.D Thesis-A. Omaka; Mcmaster University-History

MERCY ANGELS: THE JOINT CHURCH AID AND THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE IN BIAFRA, 1967-1970 BY ARUA OKO OMAKA, BA, MA A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2014), Hamilton, Ontario (History) TITLE: Mercy Angels: The Joint Church Aid and the Humanitarian Response in Biafra, 1967-1970 AUTHOR: Arua Oko Omaka, BA (University of Nigeria), MA (University of Nigeria) SUPERVISOR: Professor Bonny Ibhawoh NUMBER OF PAGES: xi, 271 ii Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History ILLUSTRATIONS Figures 1. AJEEBR`s sponsored advertisement ..................................................................122 2. ACKBA`s sponsored advertisement ...................................................................125 3. Malnourished Biafran baby .................................................................................217 Tables 1. WCC`s sickbays and refugee camp medical support returns, November 30, 1969 .....................................................................................................................171 2. Average monthly deliveries to Uli from September 1968 to January 1970.........197 Map 1. Proposed relief delivery routes ............................................................................208 iii Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History ABSTRACT International humanitarian organizations played a prominent role -

Nigeria Conflict Re-Interview (Emergency Response

This PDF generated by kmcgee, 8/18/2017 11:01:05 AM Sections: 11, Sub-sections: 0, Questionnaire created by akuffoamankwah, 8/2/2017 7:42:50 PM Questions: 130. Last modified by kmcgee, 8/18/2017 3:00:07 PM Questions with enabling conditions: 81 Questions with validation conditions: 14 Shared with: Rosters: 3 asharma (never edited) Variables: 0 asharma (never edited) menaalf (never edited) favour (never edited) l2nguyen (last edited 8/9/2017 8:12:28 PM) heidikaila (never edited) Nigeria Conflict Re- interview (Emergency Response Qx) [A] COVER No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 18, Static texts: 1. [1] DISPLACEMENT No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 6. [2] HOUSEHOLD ROSTER - BASIC INFORMATION No sub-sections, Rosters: 1, Questions: 14, Static texts: 1. [3] EDUCATION No sub-sections, Rosters: 1, Questions: 3. [4] MAIN INCOME SOURCE FOR HOUSEHOLD No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 14, Static texts: 1. [5] MAIN EMPLOYMENT OF HOUSEHOLD No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 6, Static texts: 1. [6] ASSETS No sub-sections, Rosters: 1, Questions: 12, Static texts: 1. [7] FOOD AND MARKET ACCESS No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 21. [8] VULNERABILITY MEASURE: COPING STRATEGIES INDEX No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 6. [9] WATER ACCESS AND QUALITY No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 22. [10] INTERVIEW RESULT No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 8, Static texts: 1. APPENDIX A — VALIDATION CONDITIONS AND MESSAGES APPENDIX B — OPTIONS LEGEND 1 / 24 [A] COVER Household ID (hhid) NUMERIC: INTEGER hhid SCOPE: IDENTIFYING -

South – East Zone

South – East Zone Abia State Contact Number/Enquires ‐08036725051 S/N City / Town Street Address 1 Aba Abia State Polytechnic, Aba 2 Aba Aba Main Park (Asa Road) 3 Aba Ogbor Hill (Opobo Junction) 4 Aba Iheoji Market (Ohanku, Aba) 5 Aba Osisioma By Express 6 Aba Eziama Aba North (Pz) 7 Aba 222 Clifford Road (Agm Church) 8 Aba Aba Town Hall, L.G Hqr, Aba South 9 Aba A.G.C. 39 Osusu Rd, Aba North 10 Aba A.G.C. 22 Ikonne Street, Aba North 11 Aba A.G.C. 252 Faulks Road, Aba North 12 Aba A.G.C. 84 Ohanku Road, Aba South 13 Aba A.G.C. Ukaegbu Ogbor Hill, Aba North 14 Aba A.G.C. Ozuitem, Aba South 15 Aba A.G.C. 55 Ogbonna Rd, Aba North 16 Aba Sda, 1 School Rd, Aba South 17 Aba Our Lady Of Rose Cath. Ngwa Rd, Aba South 18 Aba Abia State University Teaching Hospital – Hospital Road, Aba 19 Aba Ama Ogbonna/Osusu, Aba 20 Aba Ahia Ohuru, Aba 21 Aba Abayi Ariaria, Aba 22 Aba Seven ‐ Up Ogbor Hill, Aba 23 Aba Asa Nnetu – Spair Parts Market, Aba 24 Aba Zonal Board/Afor Une, Aba 25 Aba Obohia ‐ Our Lady Of Fatima, Aba 26 Aba Mr Bigs – Factory Road, Aba 27 Aba Ph Rd ‐ Udenwanyi, Aba 28 Aba Tony‐ Mas Becoz Fast Food‐ Umuode By Express, Aba 29 Aba Okpu Umuobo – By Aba Owerri Road, Aba 30 Aba Obikabia Junction – Ogbor Hill, Aba 31 Aba Ihemelandu – Evina, Aba 32 Aba East Street By Azikiwe – New Era Hospital, Aba 33 Aba Owerri – Aba Primary School, Aba 34 Aba Nigeria Breweries – Industrial Road, Aba 35 Aba Orie Ohabiam Market, Aba 36 Aba Jubilee By Asa Road, Aba 37 Aba St. -

Imperatives and Significance of Igbo Traditional Practices of Ancient Bende Indigenes of Abia State, South-East, Nigeria

International Journal of Development and Sustainability ISSN: 2186-8662 – www.isdsnet.com/ijds Volume 7 Number 1 (2018): Pages 250-268 ISDS Article ID: IJDS17102402 Imperatives and significance of Igbo traditional practices of ancient Bende indigenes of Abia State, south-east, Nigeria Christian Chima Chukwu 1*, Florence Nneka Chukwu 1, Okeychukwu Anyaoha 2 1 Department of Sociology/Intelligence and Security Studies, Novena University, Ogume, Delta State, Nigeria 2 Department of Sociology, Imo State University, Owerri, Nigeria Abstract The overriding concern of this paper is to highlight that Ọkpukpere-chi has a critical mandate in the affairs of respective Bende communities, and represents a solemn communion with Chineke the supreme power as the creator of everything (visible and invisible) and the source of other deities. How truly involved are the people in the practice of Ọkpukpere-chi? And, to what extent has its practice guarantee social stability within the Bende communities? This study articulates the idea of that Ọkpukpere-chi anchors its existence on only, but one Supreme Being: Chineke (God) and many lower supernatural beings or deities (Arusi).The world view of Ọkpukpere-chi cements relations among the various Bende communities. This assertion is clearly reflected in the way and manner that, Ọkpukpere-chi practice in more ways than one, served as an umbilical cord which connected and coordinated all other facets of life. All activities in the society, whether farming, hunting, marketing, social relations, and even recreation are governed by laws and taboos, and all blend inextricably in a complicated ritual with a view to throwing light on its structure, functions and modus operandi. -

List of Community Banks Converted to Microfinance Banks As at 31St

CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA IMPORTANT NOTICE LIST OF COMMUNITY BANKS THAT HAVE SUCESSFULLY CONVERTED TO MICROFINANCE BANKS AS AT DECEMBER 31, 2007 Following the expiration of December 31, 2007 deadline for all existing community banks to re-capitalize to a minimum of N20 million shareholders’ fund, unimpaired by losses, and consequently convert to microfinance banks (MFB), it is imperative to publish the outcome of the conversion exercise for the guidance of the general public. Accordingly, the attached list represents 607 erstwhile community banks that have successfully converted to microfinance banks with either final licence or provisional approval. This list does not, however, include new investors that have been granted Final Licences or Approvals-In- Principle to operate as microfinance banks since the launch of Microfinance Policy on December 15, 2005. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) hereby states categorically that only the community banks on this list that have successfully converted to microfinance banks shall continue to be supervised by the CBN. Members of the public are hereby advised not to transact business with any community bank which is not on the list of these successfully converted microfinance banks. Any member of the public, who transacts business with any community bank that failed to convert to MFB does so at his/her own risk. Members of the public are also to note that the operating licences of community banks that failed to re-capitalize and consequently do not appear on this list, have automatically been revoked pursuant to Section 12 of BOFIA, 1991 (as amended). For the avoidance of the doubt, new applications either as a Unit or State Microfinance Banks from potential investors or promoters shall continue to be received and processed for licensing by the Central Bank of Nigeria. -

Harnischfeger Igbo Nationalism & Biafra Long Paper

Igbo Nationalism and Biafra Johannes Harnischfeger, Frankfurt Content 0. Foreword .................................................................... 3 1. Introduction 1.1 The War and its Legacy ....................................... 8 1.2 Trapped in Nigeria.............................................. 13 1.2 Nationalism, Religion, and Global Identities....... 17 2. Patterns of Ethnic and Regional Conflicts 2.1 Early Nationalism ............................................... 23 2.2 The Road to Secession ...................................... 31 3. The Defeat of Biafra 3.1 Left Alone ........................................................... 38 3.2 After the War ...................................................... 44 4. Global Identities and Religion 4.1 9/11 in Nigeria .................................................... 52 4.2 Christian Solidarity ............................................. 59 5. Nationalist Organisations 5.1 Igbo Presidency or Secession............................ 64 2 5.2 Internal Divisions ................................................ 70 6. Defining Igboness 6.1 Reaching for the Stars........................................ 74 6.2 Secular and Religious Nationalism..................... 81 7. A Secular, Afrocentric Vision 7.1 A Community of Suffering .................................. 86 7.2 Roots .................................................................. 91 7.3 Modernism.......................................................... 97 8. The Covenant with God 8.1 In Exile............................................................. -

ABIA ORGANIZED CRIME FACTS.Cdr

ORGANIZED CRIME FACTS ABIA STATE Abia State with an estimated population of 2.4 million and records straight. predominantly of Igbo origin, has recently come under the limelight due to heightened insecurity trailing South-Eastern Through its bi-annual publications of organized crime facts states. With the spike in attacks of police officers and police of each of the states in Nigeria, Eons Intelligence attempts stations, correctional facilities and other notable public and to augment the dearth of updated and timely release of private properties and persons in some selected Eastern national crime statistics by objectively providing an States of the Nation, speculations have given rise to an assessment of the situation to provide answers that will underlying tone that denotes all Eastern States as assist all stakeholders to make an informed decision. presenting an uncongenial image of a hazardous zone, Abia State, which shares a boundary with Imo State to the which fast deteriorates into a notorious terrorist region. West, has started gaining the reputation for being one of the The myth of more violent South-Eastern States than their violent Eastern states in the light of recent insecurity Northern counterparts cuts across all social media and happenings in Imo State. Some detractors have gone to the social status amongst the elites, expatriates, the rich, the extent of relying on personal perceptions, presumptions, poor, and the ugly, sending culpable fears amidst all. one-off incidents, conspiracy deductions, the power of invisible forces, or the scramble for resources to form an Hence, it is necessary to use verified statistics that use a opinion. -

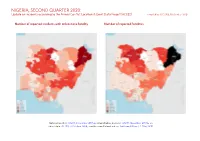

NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020

NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 3 October 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 356 233 825 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 246 200 1257 Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 2 Protests 141 1 1 Explosions / Remote Methodology 3 77 67 855 violence Conflict incidents per province 4 Riots 75 26 42 Strategic developments 18 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 913 527 2980 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). 2 NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Induction Strategy of Igbo Entrepreneurs and Micro-Business Success

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS, 4 (2016) 43–65 DOI: 10 .1515/auseb-2016-0003 Induction Strategy of Igbo Entrepreneurs and Micro-Business Success: A Study of Household Equipment Line, Main Market Onitsha, Nigeria Obunike CHINAZOR LADY-FRANCA Federal University Ndufu-Alike, Ikwo, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Department of Business Administration/Entrepreneurial Studies P .M .B . 1010, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State, Nigeria e-mail: ladyfranca8@gmail .com Abstract. This work justifies the “Igba-odibo” (Traditional Business School) concept as a business strategy for achieving success in business which is measured through business/opportunity utilization, customer relationship/ business networking and capital acquisition for business . It gives the in-depth symbolic interpretation and application of the dependent and independent variables used. The paper extends its discussion on the significance of these business strategies as practised among Igbo entrepreneurs and on how they equip Igbo entrepreneurs to immensely contribute their quotas in the area of developing entrepreneurship in Nigeria in particular and the globe in general . Research questions were formulated to investigate the relationship between business strategy and success . Related literature was reviewed . The study population covers the household equipment line of Main Market Onitsha in Anambra State, Nigeria, which has shop capacities of over five hundred, which were used to assume the population of the study – out of the 300 questionnaires administered to the directors of the business or the Masters/Mistresses, who were the business owners during the study, 180 were returned, 73 were invalid, so the researcher was left with 107 valid questionnaires to work with . The data collected were tested using frequency tables, percentages, Pearson Product-Moment correlation analysis, and regression analysis . -

The Land Has Changed: History, Society and Gender in Colonial Eastern Nigeria

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2010 The land has changed: history, society and gender in colonial Eastern Nigeria Korieh, Chima J. University of Calgary Press Chima J. Korieh. "The land has changed: history, society and gender in colonial Eastern Nigeria". Series: Africa, missing voices series 6, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2010. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/48254 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com THE LAND HAS CHANGED History, Society and Gender in Colonial Eastern Nigeria Chima J. Korieh ISBN 978-1-55238-545-6 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Complexity As Aesthetics in the Iri-Agha of the Ohafia Igbo People

International Journal of February, 2020 Development Strategies in Humanities, Management and Social Sciences IJDSHMSS p-ISSN: 2360-9036 | e-ISSN: 2360-9044 Vol. 10, No. 1 Complexity as Aesthetics in the Iri-Agha of the Ohafia Igbo People Omeh Obasi Ngwoke A b s t r a c t Department of English Studies, Faculty of Humanities, ery little is known of the diverse forms of African University of Port Harcourt, folklore, especially those with literary and artistic Port Harcourt, Nigeria Vmerit in spite of their pervasive presence within the continent and their unabated practice among the peoples that own them. As part of the efforts in filling this critical gap, this paper examines one of such forms among the Ohafia Igbo people of eastern Nigeria named the Iri-Agha - that is “war dance” in English. The essay's contention is that though a few studies have been carried out on the highly artistic and massively enjoyed dramatic enactment of the indigenous people, no scholarship exists in the area of its complexity of form. Here then lies the focus and significance of this essay which seeks to examine the intricacies of the traditional performance's formal features. The study deploys the method of qualitative ethnography involving close observation and interview of the practitioners of the art in the field collection of primary Keywords: data, and the theory of ethno-poetics in the analysis the Complexity, collected data. Consequently, the study discovers that the Aesthetics, Iri-Agha, Iri-Agha depicts an artistic complexity that emanates from a War, Dance, Drama, seamless combination of materials from the dramatic, the Performance narrative and the poetic arts and a blending of these with resources from the plastic and decorative arts.