FAA Aerospace Forecast FY 2018-2038

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Conceptual Design of a Short Takeoff and Landing Regional Jet Airliner

A Conceptual Design of a Short Takeoff and Landing Regional Jet Airliner Andrew S. Hahn 1 NASA Langley Research Center, Hampton, VA, 23681 Most jet airliner conceptual designs adhere to conventional takeoff and landing performance. Given this predominance, takeoff and landing performance has not been critical, since it has not been an active constraint in the design. Given that the demand for air travel is projected to increase dramatically, there is interest in operational concepts, such as Metroplex operations that seek to unload the major hub airports by using underutilized surrounding regional airports, as well as using underutilized runways at the major hub airports. Both of these operations require shorter takeoff and landing performance than is currently available for airliners of approximately 100-passenger capacity. This study examines the issues of modeling performance in this now critical flight regime as well as the impact of progressively reducing takeoff and landing field length requirements on the aircraft’s characteristics. Nomenclature CTOL = conventional takeoff and landing FAA = Federal Aviation Administration FAR = Federal Aviation Regulation RJ = regional jet STOL = short takeoff and landing UCD = three-dimensional Weissinger lifting line aerodynamics program I. Introduction EMAND for air travel over the next fifty to D seventy-five years has been projected to be as high as three times that of today. Given that the major airport hubs are already congested, and that the ability to increase capacity at these airports by building more full- size runways is limited, unconventional solutions are being considered to accommodate the projected increased demand. Two possible solutions being considered are: Metroplex operations, and using existing underutilized runways at the major hub airports. -

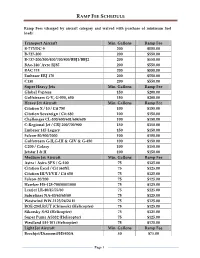

Ramp Fee Schedule

RAMP FEE SCHEDULE Ramp Fees (charged by aircraft category and waived with purchase of minimum fuel load): Transport Aircraft Min. Gallons Ramp Fee B-717/DC-9 200 $550.00 B-727-200 200 $550.00 B-737-200/300/400/700/800/BBJ1/BBJ2 200 $550.00 BAe-146/ Avro RJ85 200 $550.00 BAC 111 200 $550.00 Embraer ERJ 170 200 $550.00 C130 200 $550.00 Super Heavy Jets Min. Gallons Ramp Fee Global Express 150 $200.00 Gulfstream G-V, G-550, 650 150 $200.00 Heavy Jet Aircraft Min. Gallons Ramp Fee Citation X / 10 / Cit 750 100 $150.00 Citation Sovereign / Cit 680 100 $150.00 Challenger CL-300/600/601/604/605 100 $150.00 C-Regional Jet / CRJ 200/700/900 150 $150.00 Embraer 145 Legacy 150 $150.00 Falcon-50/900/2000 100 $150.00 Gulfstream G-II,G-III & GIV & G-450 100 $150.00 G200 / Galaxy 100 $150.00 Jetstar I & II 100 $150.00 Medium Jet Aircraft Min. Gallons Ramp Fee Astra / Astra SPX / G-100 75 $125.00 Citation Excel / Cit 560XL 75 $125.00 Citation III/VI/VII / Cit 650 75 $125.00 Falcon-20/200 75 $125.00 Hawker HS-125-700/800/1000 75 $125.00 Learjet LR-40/45/55/60 75 $125.00 Sabreliner NA-40/60/65/80 75 $125.00 Westwind WW-1123/24/24 II 75 $125.00 BOE-234LR/UT (Chinook) (Helicopter) 75 $125.00 Sikorsky S-92 (Helicopter) 75 $125.00 Super Puma AS332 (Helicopter) 75 $125.00 Westland EH-101 (Helicopter) 75 $125.00 Light Jet Aircraft Min. -

Global Fleet & Mro Market Forecast Summary

GLOBAL FLEET & MRO MARKET FORECAST SUMMARY 2017-2027 AUTHORS Tom Cooper, Vice President John Smiley, Senior Manager Chad Porter, Technical Specialist Chris Precourt, Technical Analyst For over a decade, Oliver Wyman has surveyed aviation and aerospace senior executives and industry influencers about key trends and challenges across the Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul market. If you are responsible for maintenance and engineering activities at a carrier, aftermarket activities at an OEM, business operations at an MRO, or a lessor, you may want to participate in our survey. For more information, please contact our survey team at: [email protected]. To read last year’s survey, please see: http://www.oliverwyman.com/our-expertise/insights/2016/apr/mro-survey-2016.html . CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 2. STATE OF THE INDUSTRY 5 Global Economic Outlook 7 Economic Drivers 11 3. FLEET FORECAST 17 In-Service Fleet Forecast 18 4. MRO MARKET FORECAST 31 Copyright © Oliver Wyman 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Oliver Wyman’s 2017 assessment and 10-year outlook for the commercial airline transport fleet and the associated maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) market marks the 17th year of supporting the industry with informed, validated industry data. This has become the most credible go-to forecast for many executives in the airline and MRO industry as well as for those with financial interests in the sector, such as private equity firms, investment banks and investment analysts. The global airline industry has made radical changes in the last few years and is producing strong financial results. While the degree of success varies among the world regions, favorable fuel prices and widespread capacity discipline are regarded as key elements in the 2016 record high in global profitability ($35.6 billion). -

Chapter Iv Regionals/Commuters

CHAPTER IV REGIONALS/COMMUTERS For purposes of the Federal Aviation REVIEW OF 20032 Administration (FAA) forecasts, air carriers that are included as part of the regional/commuter airline industry meet three criteria. First, a The results for the regional/commuter industry for regional/commuter carrier flies a majority of their 2003 reflect the continuation of a trend that started available seat miles (ASMs) using aircraft having with the events of September 11th and have been 70 seats or less. Secondly, the service provided by drawn out by the Iraq War and Severe Acute these carriers is primarily regularly scheduled Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). These “shocks” to passenger service. Thirdly, the primary mission of the system have led to the large air carriers posting the carrier is to provide connecting service for its losses in passengers for 3 years running. The code-share partners. losses often reflect diversions in traffic to the regional/commuter carriers. These carriers During 2003, 75 reporting regional/commuter recorded double-digit growth in both capacity and airlines met this definition. Monthly traffic data for traffic for the second time in as many years. History 10 of these carriers was compiled from the has demonstrated that the regional/commuter Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Form 41 industry endures periods of uncertainty better than and T-100 filings. Traffic for the remaining the larger air carriers. During the oil embargo of 65 carriers was compiled solely from T-100 filings. 1 1973, the recession in 1990, and the Gulf War in Prior to fiscal year 2003, 10 regionals/commuters 1991, the regional/commuter industry consistently reported on DOT Form 41 while 65 smaller outperformed the larger air carriers. -

Technological Innovation in the Airline Industry: the Impact of Regional Jets

Technological Innovation in the Airline Industry: The Impact of Regional Jets by Jan K. Brueckner Department of Economics University of California, Irvine 3151 Social Science Plaza Irvine, CA 92697 e-mail: [email protected] and Vivek Pai Department of Economics University of California, Irvine 3151 Social Science Plaza Irvine, CA 92697 e-mail: [email protected] February 2007 Abstract This paper explores the impact of the regional jet (RJ), an important new technological inno- vation in the airline industry, on service patterns and service quality. The evidence shows that RJs were used to provide service on a large number of new hub-and-spoke (HS) and point-to- point (PP) routes. In addition, they replaced discontinued jet and turboprop service on many HS routes, as well as supplementing continuing jet service on such routes. When replace- ment or supplementation by RJs occurred, passengers benefited from better service quality via higher flight frequencies. The paper’s theoretical analysis predicts that the frequency ad- vantage of RJs over jets, a consequence of their small size, should have led to the emergence of PP service in thin markets where such service was previously uneconomical. However, the evidence contradicts this prediction, showing that markets attracting new PP service by RJs had demographic characteristics similar to those of markets that already had jet PP service or attracted it after 1996. Technological Innovation in the Airline Industry: The Impact of Regional Jets by Jan K. Brueckner and Vivek Pai 1. Introduction While the airline industry has experienced a number of significant institutional innovations over the years, including the adoption of hub-and-spoke networks and frequent flier programs and the use of yield management techniques, true technological innovations have been less fre- quent. -

Aviation Activity Forecasts

2 Aviation Activity Forecasts INTRODUCTION The Charles M. Schulz–Sonoma County Airport (STS) is one of six public use airports in Sonoma County. It is the only commercial service airport1 between the San Francisco Bay Area to the south, Sacramento to the east and Arcata-Eureka to the north. The Airport’s primary service area has a population of over 1 million people2 and includes Sonoma, Lake, and Mendocino counties, and parts of Marin and Napa counties. Airport Role The Sonoma County Airport, as the region’s principal Airport, serves many roles, including providing facilities for scheduled commuter and air carrier airline services. The California Aviation System Plan (CASP) designates the Airport as a Primary Commercial Service Non-Hub Airport. There are no Primary Commercial Service Hub airports in the region. The closest Primary Commercial Service Hub airports are the San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose International Airports. The Sacramento International Airport is slightly more distant, but at times it can be more convenient for highway travel. The Sonoma County Airport also serves a growing population of general aviation (GA) activities including corporate and business flying. For this reason, the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS) currently classifies the Airport as a General Aviation facility, but in the future the Airport is expected to be reclassified as a Commercial Service Non-Primary Airport. A strong potential exists for additional scheduled airline and commuter air carrier service, particularly in the form of new, quiet technology jet aircraft with up to 135 passenger seats.3 The Airport also serves as a base of operations for local pilots, a place to conduct business, and a point of emergency access for the region. -

The Evolution of U.S. Commercial Domestic Aircraft Operations from 1991 to 2010

THE EVOLUTION OF U.S. COMMERCIAL DOMESTIC AIRCRAFT OPERATIONS FROM 1991 TO 2010 by MASSACHUSETTS INSTME OF TECHNOLOGY ALEXANDER ANDREW WULZ UL02 1 B.S., Aerospace Engineering University of Notre Dame (2008) Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics in PartialFulfillment of the Requirementsfor the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2012 0 2012 Alexander Andrew Wulz. All rights reserved. .The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author ..................................................................... .. ...................... Department of Aeronautr and Astronautics n n May 11, 2012 Certified by ............................................................................ Peter P. Belobaba Principle Research Scientist of Aeronautics and Astronautics / Thesis Supervisor A ccepted by ................................................................... Eytan H. Modiano Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics Chair, Graduate Program Committee 1 PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 THE EVOLUTION OF U.S. COMMERCIAL DOMESTIC AIRCRAFT OPERATIONS FROM 1991 TO 2010 by ALEXANDER ANDREW WULZ Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics on May 11, 2012 in PartialFulfillment of the Requirementsfor the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS ABSTRACT The main objective of this thesis is to explore the evolution of U.S. commercial domestic aircraft operations from 1991 to 2010 and describe the implications for future U.S. commercial domestic fleets. Using data collected from the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics, we analyze 110 different aircraft types from 145 airlines operating U.S. commercial domestic service between 1991 and 2010. We classify the aircraft analyzed into four categories: turboprop, regional jet, narrow-body, and wide-body. -

The Changing Face of Air Travel

The Changing Face of Air Travel More aircraft aloft but fewer seats... blame the boom on Asia, where the desire to travel has given a new lease on life to the airline industry. The menu at this traditional Bavarian restaurant was trillion in 2011, with the steepest rate of growth in hard to read, even before the beers. It was all in Southeast Asia. Oddly, the terrorist attacks on the Chinese. Paulaner’s Bremen on the German North World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2000, as Sea coast has bowed to reality and begun well as the SARS epidemic and the 2008/9 financial communicating directly with their Chinese guests, at crisis barely impacted the growth rate of least through their menu. international travel, which continues to grow nearly 5 percent each year. The growth of Asian travel also The number of Chinese tourists visiting Europe is reflects the increase in global trade. expected to multiply in the coming years as consumers in the Asian country acquire wealth and Airbus estimates that airlines in the Asia-Pacific venture out into the world. According to the region will take delivery of around 9,370 new European Commission, the number of visa aircraft over the next 20 years – a book value of 1.3 applications in China for travel to Europe surged to trillion dollars. The Brazilian regional jet maker, 1.03 million annually in 2011 – an 81 percent Embraer, says China alone will need 1005 new short- increase over 2008. haul aircraft by 2031 to accommodate the increase in air travel. -

Federal Register/Vol. 81, No. 90/Tuesday, May 10

28770 Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 90 / Tuesday, May 10, 2016 / Proposed Rules List of Subjects in 14 CFR Part 39 has the authority to approve AMOCs for this ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking AD, if requested using the procedures found (NPRM). Air transportation, Aircraft, Aviation in 14 CFR 39.19. In accordance with 14 CFR safety, Incorporation by reference, 39.19, send your request to your principal SUMMARY: We propose to adopt a new Safety. inspector or local Flight Standards District airworthiness directive (AD) for all The The Proposed Amendment Office, as appropriate. If sending information Boeing Company Model DC–10–10 and directly to the ACO, send it to ATTN: DC–10–10F airplanes, Model DC–10–15 Accordingly, under the authority Program Manager, Continuing Operational airplanes, Model DC–10–30 and DC–10– delegated to me by the Administrator, Safety, FAA, New York ACO, 1600 Stewart 30F (KC–10A and KDC–10) airplanes, Avenue, Suite 410, Westbury, NY 11590; the FAA proposes to amend 14 CFR part Model DC–10–40 and DC–10–40F 39 as follows: telephone 516–228–7300; fax 516–794–5531. Before using any approved AMOC, notify airplanes, Model MD–10–10F and MD– PART 39—AIRWORTHINESS your appropriate principal inspector, or 10–30F airplanes, and Model MD–11 DIRECTIVES lacking a principal inspector, the manager of and MD–11F airplanes. This proposed the local flight standards district office/ AD was prompted by results from fuel ■ 1. The authority citation for part 39 certificate holding district office. The AMOC system reviews conducted by the continues to read as follows: approval letter must specifically reference manufacturer and multiple reports of this AD. -

The 50-Seat Jet: a Plane with No Future. Think Again!

Aviation, Aerospace & Defense The 50-Seat Jet: A Plane With No Future. Think again! Manufacturers are shutting down production of 50-seat jets in the face of empty order books and changing economics. What are the options for operators with low-volume routes to serve and aging fleets to replace? A solution is necessary, and the industry must work together to find it. he low-density, sub 1,000 mile (1,600 km) consumption and lower pilot costs. Relative to the Tmarket, profitably built upon the capabilities mainlines flying a larger aircraft on the same route, and economics of the 50-seat jet, faces a crisis. Once a regional airline flying a 50-seater could achieve the great competitive hope of the regional airline higher revenue per available seat mile and feed industry, 50-seat jets are now becoming a liability the rest of the network. The long-term, fixed-fee that the industry as a whole needs to address to contracts (capacity purchase agreements, or CPAs) move forward. All the obvious stakeholders in this that the regional airlines signed with the mainlines issue – OEMs looking to provide other options, afforded them margin protection while eliminating regional airlines serving routes up to 1,000 miles, revenue risk, and provided them the ability to and major airlines tied to these regionals by concentrate on rationalizing cost. capacity purchase agreements (CPAs)—will face the consequences of an aging fleet with no obvious 50-seat regional jets were first introduced to the replacement. Ripples from this crisis will also aviation market in 1995 by Bombardier in the form extend through the financiers, lessors, and insurers of its CRJ-200 jet. -

GECAS -- Above & Beyond

GECAS ABOVE & BEYOND g GECAS is a world-leading aviation and lessor and financier. For over five decades, we have solved our customers’ challenges and enabled their businesses to thrive. Whether your need is for aircraft, engines, helicopters or materials, our name has become synonymous with trusted relationships, domain expertise and delivering on our promises. GECAS. Ready for our second fifty years. GECAS is the global commercial aircraft Now with a fleet of 1,900 aircraft and financing and leasing business of GE. helicopters, GECAS offers the largest fleet Our story began in 1967, when we and widest array of solutions to customer contracted our first aircraft lease needs. With a modern, innovative fleet in agreement, a landmark that would help service and on order, GECAS is ready to launch a new industry, allow easier access drive your business higher. to capital for the world’s rapidly expanding airline industry and enable lower cost air travel for millions of travelers. T HE GECAS DIFFERENCE GECAS works with you to solve complex GECAS proudly serves ~250 customers across questions that will enable your business to more than 75 countries – from startups to thrive. We are a passionate team of experts that flagship airlines, from regionals to low cost draw on deep domain knowledge and global carriers, from cargo airlines to helicopter resources to create win-win partnerships for operators. The breadth and depth of our operators, financiers and investors. customer base speaks to the strength of our GECAS offers the industry’s widest array of relationships. We understand your business. leasing solutions. -

Rise and Fall of the Regional Jet by Brian K. Sedghi a Thesis Submitted

Rise and Fall of the Regional Jet by Brian K. Sedghi A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Aviation Management Middle Tennessee State University 2013 Thesis Committee: Dr. Ronald J. Ferrara, Chair Dr. Wendy Beckman I dedicate this research to all of the people that have supported me through my college career. Friends, family, faculty, and peers have believed in me throughout my student career and I am sure that none of what I have accomplished during my time at Middle Tennessee State University would have been possible without their continuous support and mentoring. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout the completion of this project and my college career I have had many ups and many more downs but through the continued support of my friends, family, and the faculty of Middle Tennessee State University I have persevered toward the completion of my goals and aspirations to take away from the University. I would not be where I am today without their support and guidance and am thankful to have been part of such a great University. I would like to extend as special thanks to Dr. Wendy Beckman and Dr. Ron Ferrara for their continued support throughout this project. Though I’m sure I have been agonizing at times to deal with, they have stuck with me and helped me towards the completion of this feat of a project. ii ABSTRACT Over the course of more than two decades, the aviation industry has seen the introduction of the regional jet and witnessed the many operational benefits that it has presented airlines.