The Muscle Relaxants in Infants and Children*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muscle Relaxants Femoral Arteriography.,,>

IN THIS ISSUE: , .:t.i ". Muscle Relaxants fI, \'.' \., Femoral ArteriographY.,,> University of Minnesota Medical Bulletin Editor ROBERT B. HOWARD, M.D. Associate Editors RAY M. AMBERG GILBERT S. CAMPBELL, M.D. ELLIS S. BENSON, MD. BYRON B. COCHRANE, M.D. E. B. BROWN, PhD. RICHARD T. SMITH, M.D. WESLEY W. SPINK, MD. University of Minnesota Medical School J. 1. MORRILL, President, University of Minnesota HAROLD S. DIEHL, MD., Dean, College of Medical SciencBs WILLIAM F. MALONEY, M.D., Assistant Dean N. 1. GAULT, JR., MD., Assistant Dean University Hospitals RAY M. AMBERG, Director Minnesota Medical Foundation WESLEY W. SPINK, M.D., President R. S. YLVISAKER, MD., Vice-President ROBERT B. HOWARD, M.D., Secretary-Treasurer Minnesota Medical Alumni Association BYRON B. COCHRANE, M.D., President VIRGIL J. P. LUNDQUIST, M.D., First Vice-President SHELDON M. LAGAARD, MD., Second Vice-President LEONARD A. BOROWICZ, M.D., Secretary JAMES C. MANKEY, M.D., Treasurer UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Medical Bulletin OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA HOSPITALS, MINNE· SOTA MEDICAL FOUNDATION, AND MINNESOTA MEDICAL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION VOLUME XXVIII December 1, 1956 NUMBER 4 CONTENTS STAFF MEETING REPORTS Current Status of Muscle Relaxants BY J. Albert Jackson, MD., J. H. Matthews, M.D., J. J. Buckley, M.D., D.S.P. Weatherhead, M.D., AND F. H. Van Bergen, M.D. 114 Small Vessel Changes in Femoral Arteriography BY Alexander R. Margulis, M.D. AND T. O. Murphy, MD.__ 123 EDITORIALS .. - -. - ---__ __ _ 132 MEDICAL SCHOOL ACTIVITIES ----------- 133 POSTGRADUATE EDUCATION - 135 COMING EVENTS 136 PIIb1ished semi.monthly from October 15 to JUDe 15 at Minneapolis, Minnesota. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0024365A1 Vaya Et Al

US 2006.0024.365A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0024365A1 Vaya et al. (43) Pub. Date: Feb. 2, 2006 (54) NOVEL DOSAGE FORM (30) Foreign Application Priority Data (76) Inventors: Navin Vaya, Gujarat (IN); Rajesh Aug. 5, 2002 (IN)................................. 699/MUM/2002 Singh Karan, Gujarat (IN); Sunil Aug. 5, 2002 (IN). ... 697/MUM/2002 Sadanand, Gujarat (IN); Vinod Kumar Jan. 22, 2003 (IN)................................... 80/MUM/2003 Gupta, Gujarat (IN) Jan. 22, 2003 (IN)................................... 82/MUM/2003 Correspondence Address: Publication Classification HEDMAN & COSTIGAN P.C. (51) Int. Cl. 1185 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS A6IK 9/22 (2006.01) NEW YORK, NY 10036 (US) (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 424/468 (22) Filed: May 19, 2005 A dosage form comprising of a high dose, high Solubility active ingredient as modified release and a low dose active ingredient as immediate release where the weight ratio of Related U.S. Application Data immediate release active ingredient and modified release active ingredient is from 1:10 to 1:15000 and the weight of (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 10/630,446, modified release active ingredient per unit is from 500 mg to filed on Jul. 29, 2003. 1500 mg, a process for preparing the dosage form. Patent Application Publication Feb. 2, 2006 Sheet 1 of 10 US 2006/0024.365A1 FIGURE 1 FIGURE 2 FIGURE 3 Patent Application Publication Feb. 2, 2006 Sheet 2 of 10 US 2006/0024.365A1 FIGURE 4 (a) 7 FIGURE 4 (b) Patent Application Publication Feb. 2, 2006 Sheet 3 of 10 US 2006/0024.365 A1 FIGURE 5 100 ov -- 60 40 20 C 2 4. -

Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Muscle Relaxants

i ,I .. / ,""- Clinical Pharmacokinetics 2: 330-343 (1977) © ADIS Press 1977 Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Muscle Relaxants L.B. Wingard and DR. Cook Departments of Pharmacology and Anesthesiology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania SUl1lmary Muscle relaxants are commonly used as an adjunct to general anaesthesia and to facilitate ventilator care in the intensive care unit. The muscle relaxants are unique in that the degree of neurol1luscular blockade can be directly measured. Thus, for some of the muscle relaxants it is possible to correlate the degree of neuromuscular blockade with the plasma concentration of drug. This quantilalive pllGrmacokinelic approach has been applied primarily to d tubocurarine and to a lesser extent to suxamethonium (succinylcholine), gallamine and pan curoniul1l. The pharl1lacokinetic information for the other relaxants is mostly descriptive and incomplete. The variation in drug concentration over time is in.fluenced by the distribution, metabolism and excretion of drug. Metabolism by plasma cholinesterase plays a maJor role in the termina tion (~f action of suxamethonium. Although pancuronium is partly metabolised its major metabolites have moderate pharmacological activity. The other relaxants are excreted through the kidney. For gallamine and dimethyl-tubocurarine, renal excretion appears to be the only means qf eliinination. However, biliary excretion probably provides an alternative route of elimination for d-tubocurarine and pancuronium. In patients with impaired renal function the duration qf neuromusClilar blockade may be markedly prolonged following standard doses of gallamine or dimethyl-tubocurarine, may be slightly prolonged following standard doses of pancumnium, and is near normal following standard doses qf d-tubocurarine. Following large or repeated doses q(pancuronium or d-tubocurarine, the duration q{ neuromuscular blockade may be markedly prolonged. -

Multidrug Treatment with Nelfinavir and Cepharanthine Against COVID-19

Supplemental Information Multidrug treatment with nelfinavir and cepharanthine against COVID-19 Hirofumi Ohashi1,2,¶, Koichi Watashi1,2,3,4*, Wakana Saso1,5.6,¶, Kaho Shionoya1,2, Shoya Iwanami7, Takatsugu Hirokawa8,9,10, Tsuyoshi Shirai11, Shigehiko Kanaya12, Yusuke Ito7, Kwang Su Kim7, Kazane Nishioka1,2, Shuji Ando13, Keisuke Ejima14, Yoshiki Koizumi15, Tomohiro Tanaka16, Shin Aoki16,17, Kouji Kuramochi2, Tadaki Suzuki18, Katsumi Maenaka19, Tetsuro Matano5,6, Masamichi Muramatsu1, Masayuki Saijo13, Kazuyuki Aihara20, Shingo Iwami4,7,21,22,23, Makoto Takeda24, Jane A. McKeating25, Takaji Wakita1 1Department of Virology II, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo 162-8640, Japan, 2Department of Applied Biological Science, Tokyo University of Science, Noda 278-8510, Japan, 3Institute for Frontier Life and Medical Sciences, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan, 4MIRAI, JST, Saitama 332-0012, Japan, 5The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 108-8639, Japan, 6AIDS Research Center, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo 162-8640, Japan, 7Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka 812-8581, Japan, 8Cellular and Molecular Biotechnology Research Institute, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Tokyo 135-0064, Japan, 9Division of Biomedical Science, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba 305-8575, Japan, 10Transborder Medical Research Center, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba 305-8575, Japan, 11Faculty of Bioscience, Nagahama Institute -

Pharmaceuticals As Environmental Contaminants

PharmaceuticalsPharmaceuticals asas EnvironmentalEnvironmental Contaminants:Contaminants: anan OverviewOverview ofof thethe ScienceScience Christian G. Daughton, Ph.D. Chief, Environmental Chemistry Branch Environmental Sciences Division National Exposure Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development Environmental Protection Agency Las Vegas, Nevada 89119 [email protected] Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Why and how do drugs contaminate the environment? What might it all mean? How do we prevent it? Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada This talk presents only a cursory overview of some of the many science issues surrounding the topic of pharmaceuticals as environmental contaminants Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada A Clarification We sometimes loosely (but incorrectly) refer to drugs, medicines, medications, or pharmaceuticals as being the substances that contaminant the environment. The actual environmental contaminants, however, are the active pharmaceutical ingredients – APIs. These terms are all often used interchangeably Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Office of Research and Development Available: http://www.epa.gov/nerlesd1/chemistry/pharma/image/drawing.pdfNational -

Pharmacological Review of Chemicals Used for the Capture of Animals

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Proceedings of the 7th Vertebrate Pest Vertebrate Pest Conference Proceedings Conference (1976) collection March 1976 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEW OF CHEMICALS USED FOR THE CAPTURE OF ANIMALS Peter J. Savarie U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/vpc7 Part of the Environmental Health and Protection Commons Savarie, Peter J., "PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEW OF CHEMICALS USED FOR THE CAPTURE OF ANIMALS" (1976). Proceedings of the 7th Vertebrate Pest Conference (1976). 41. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/vpc7/41 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vertebrate Pest Conference Proceedings collection at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the 7th Vertebrate Pest Conference (1976) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEW OF CHEMICALS USED FOR THE CAPTURE OF ANIMALS* PETEIR J. SAVARIE, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Building 16, Federal Center, Denver, Colorado 80225 ABSTRACT: A review of the literature reveals that over 60 chemicals have been used for the capture of wi l d animals, but only 30 of the most widely used chemicals are discussed in the present paper. For practical considerations these chemicals can be c l a ssified as being either (l) neuromuscular blocking agents, or (2) central nervous system (CNS) depressants. Some common neuromuscular blocking agents are d-tubocurarine, gallamine, succiny1choline, and nicotine. M99 and its derivatives, phencyclidine, and xylazine are some of the more commonly used CNS depressants. Neuromuscular blocking agents have a relatively rapid onset and short duration of action but they do not possess sedative, analgesic, or anesthetic properties. -

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH TRACRIUM7 (Atracurium Besylate)

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH TRACRIUM7 (Atracurium besylate) 10 mg/mL Injection Intravenous Skeletal Neuromuscular Blocking Agent AbbVie Corporation DATE OF PREPARATION: 8401 Trans Canada Highway November 1, 2012 St-Laurent (QC) CANADA H4S 1Z1 DATE OF LATEST REVISION: DATE OF REVISION: Control No. 158344 NOTE: TRACRIUM is a trademark of the Glaxo group of companies, AbbVie Corporation licensed use - 2 - PRODUCT MONOGRAPH NAME OF DRUG TRACRIUM7 (Atracurium Besylate Injection) THERAPEUTIC CLASSIFICATION Intravenous Skeletal Neuromuscular Blocking Agent ACTIONS AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY TRACRIUM (atracurium besylate) is a nondepolarizing, intermediate-duration, skeletal neuromuscular blocking agent. Nondepolarizing agents antagonize the neurotransmitter action of acetylcholine by binding competitively to cholinergic receptor sites on the motor end-plate. This antagonism is inhibited, and neuromuscular block reversed by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as neostigmine, edrophonium and pyridostigmine. The duration of neuromuscular blockade produced by atracurium besylate is approximately one-third to one-half the duration seen with d-tubocurarine, metocurine and pancuronium at equipotent doses. As with other nondepolarizing neuromuscular blockers, the time to onset of paralysis decreases and the duration of maximum effect increases with increasing atracurium besylate doses. INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE TRACRIUM (atracurium besylate) is indicated, as an adjunct to general anesthesia, to facilitate endotracheal intubation and to provide skeletal muscle relaxation during surgery or mechanical ventilation. It can be used most advantageously if muscle twitch response to peripheral nerve stimulation is monitored to assess degree of muscle relaxation. CONTRAINDICATIONS TRACRIUM (atracurium besylate) is contraindicated in patients known to have a hypersensitivity to atracurium. Use of atracurium from multiple-dose vials containing benzyl alcohol as a preservative is contraindicated in patients with a known sensitivity to benzyl alcohol. -

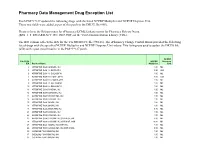

Pharmacy Data Management Drug Exception List

Pharmacy Data Management Drug Exception List Patch PSS*1*127 updated the following drugs with the listed NCPDP Multiplier and NCPDP Dispense Unit. These two fields were added as part of this patch to the DRUG file (#50). Please refer to the Release notes for ePharmacy/ECME Enhancements for Pharmacy Release Notes (BPS_1_5_EPHARMACY_RN_0907.PDF) on the VistA Documentation Library (VDL). The IEN column reflects the IEN for the VA PRODUCT file (#50.68). The ePharmacy Change Control Board provided the following list of drugs with the specified NCPDP Multiplier and NCPDP Dispense Unit values. This listing was used to update the DRUG file (#50) with a post install routine in the PSS*1*127 patch. NCPDP File 50.68 NCPDP Dispense IEN Product Name Multiplier Unit 2 ATROPINE SO4 0.4MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 3 ATROPINE SO4 1% OINT,OPH 3.50 GM 6 ATROPINE SO4 1% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 7 ATROPINE SO4 0.5% OINT,OPH 3.50 GM 8 ATROPINE SO4 0.5% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 9 ATROPINE SO4 3% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 10 ATROPINE SO4 2% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 11 ATROPINE SO4 0.1MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 12 ATROPINE SO4 0.05MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 13 ATROPINE SO4 0.4MG/0.5ML INJ 1.00 ML 14 ATROPINE SO4 0.5MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 15 ATROPINE SO4 1MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 16 ATROPINE SO4 2MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 18 ATROPINE SO4 2MG/0.7ML INJ 0.70 ML 21 ATROPINE SO4 0.3MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 22 ATROPINE SO4 0.8MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 23 ATROPINE SO4 0.1MG/ML INJ,SYRINGE,5ML 5.00 ML 24 ATROPINE SO4 0.1MG/ML INJ,SYRINGE,10ML 10.00 ML 25 ATROPINE SO4 1MG/ML INJ,AMP,1ML 1.00 ML 26 ATROPINE SO4 0.2MG/0.5ML INJ,AMP,0.5ML 0.50 ML 30 CODEINE PO4 30MG/ML -

N204-078 Neostigmine Methylsulfate Clinical PREA/BPCA

CLINICAL REVIEW Application Type NDA Application Number(s) 204078 Priority or Standard Standard Submit Date(s) July 31, 2012 Received Date(s) July 31, 2012 PDUFA Goal Date May 31, 2013 Division / Office DAAAP/ODE 2 Reviewer Name(s) Arthur Simone, MD, PhD Review Completion Date April 26, 2013 Established Name Neostigmine Methylsulfate Injection, USP (Proposed) Trade Name (b) (4) Therapeutic Class Cholinesterase Inhibitor Applicant Éclat Pharmaceuticals LLC Formulation(s) Injectable solution Dosing Regimen 30-70 mcg/kg intravenously Indication(s) Reversal of neuromuscular blocking agents after surgery Intended Population(s) Patients requiring reversal of paralysis induced with nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents Reference ID: 3300277 Clinical Review Arthur Simone, MD, PhD NDA 204078 (b) (4) (Neostigmine Methylsulfate Injection, USP) Table of Contents 1 RECOMMENDATIONS/RISK BENEFIT ASSESSMENT ......................................... 9 1.1 Recommendation on Regulatory Action ............................................................. 9 1.2 Risk Benefit Assessment .................................................................................... 9 1.3 Recommendations for Postmarket Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies . 10 1.4 Recommendations for Postmarket Requirements and Commitments .............. 10 2 INTRODUCTION AND REGULATORY BACKGROUND ...................................... 11 2.1 Product Information .......................................................................................... 11 2.2 Currently Available -

The Strychnine-Like Action of Curare and Related Compounds on the Somatosensory Evoked Response of the Rat Cortex V

Br. J. Pharmac. (1969), 37, 112-122. The strychnine-like action of curare and related compounds on the somatosensory evoked response of the rat cortex V. K. BHARGAVA AND B. S. MELDRUM Medical Research Council Neuropsychiatric Research Unit, Carshalton, Surrey 1. Drugs were applied to the cerebral cortex of rats anaesthetized with pentobarbitone and changes measured in the somatosensory primary evoked response. 2. Computer-derived averages of thirty-two consecutive responses yielded stable and consistent measurements of the potential changes comprising the evoked response, and comparable records from the opposite (non-drug treated) cortex provided an essential control for systemic actions of the drug. 3. The modifications produced by curare and strychnine were indistinguish- able. The first positive wave (peak latency 7 msec) was unaltered; the second positive wave (peak latency 11.5 msec) was variably enhanced, and the first and second negative waves (peak latencies 16 and 40 msec) were replaced by a much larger negative wave (peak latency 22 msec). 4. The time of onset of the effect on the negative waves and the maximal amplitude attained by the abnormal negative wave were related to the log con- centration of the drug used. Curare is approximately 10 times more potent than strychnine. 5. Toxiferine I, di-allylnortoxiferine and atropine also produced this effect but were less potent than strychnine. 6. Succinylcholine, dihydro-f-erythroidine and gallamine triethiodide did not produce this effect (in concentrations up to 10-3M). 7. The observations are consistent with an action of curare and strychnine on an intracortical cholinergic inhibitory system, but other possibilities includ- ing a " non-specific excitatory action " cannot be excluded. -

Drug/Substance Trade Name(S)

A B C D E F G H I J K 1 Drug/Substance Trade Name(s) Drug Class Existing Penalty Class Special Notation T1:Doping/Endangerment Level T2: Mismanagement Level Comments Methylenedioxypyrovalerone is a stimulant of the cathinone class which acts as a 3,4-methylenedioxypyprovaleroneMDPV, “bath salts” norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor. It was first developed in the 1960s by a team at 1 A Yes A A 2 Boehringer Ingelheim. No 3 Alfentanil Alfenta Narcotic used to control pain and keep patients asleep during surgery. 1 A Yes A No A Aminoxafen, Aminorex is a weight loss stimulant drug. It was withdrawn from the market after it was found Aminorex Aminoxaphen, Apiquel, to cause pulmonary hypertension. 1 A Yes A A 4 McN-742, Menocil No Amphetamine is a potent central nervous system stimulant that is used in the treatment of Amphetamine Speed, Upper 1 A Yes A A 5 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, narcolepsy, and obesity. No Anileridine is a synthetic analgesic drug and is a member of the piperidine class of analgesic Anileridine Leritine 1 A Yes A A 6 agents developed by Merck & Co. in the 1950s. No Dopamine promoter used to treat loss of muscle movement control caused by Parkinson's Apomorphine Apokyn, Ixense 1 A Yes A A 7 disease. No Recreational drug with euphoriant and stimulant properties. The effects produced by BZP are comparable to those produced by amphetamine. It is often claimed that BZP was originally Benzylpiperazine BZP 1 A Yes A A synthesized as a potential antihelminthic (anti-parasitic) agent for use in farm animals. -

14 Informe 40.Pdf

WHO Technical Report Series 937 SPECIFICATIONS This report presents the recommendations of an international WHO EXPERT COMMITTEE group of experts convened by the World Health Organization to consider matters concerning the quality assurance of ON SPECIFICATIONS FOR pharmaceuticals and specifi cations for drug substances and dosage forms. PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS FOR The report is complemented by a number of annexes. These include: a list of available International Chemical Reference PHARMACEUTICAL Substances and International Infrared Spectra; supplementary guidelines on good manufacturing practices for heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems for non-sterile pharmaceutical dosage forms; updated supplementary guidelines on good manufacturing practices for the manufacture of herbal medicines; supplementary guidelines on Fortieth Report good manufacturing practices for validation; good distribution practices for pharmaceutical products; a model quality assurance PREPARATIONS system for procurement agencies (recommendations for quality assurance systems focusing on prequalifi cation of products and manufacturers, purchasing, storage and distribution of pharmaceutical products); multisource (generic) pharmaceutical products: guidelines on registration requirements to establish interchangeability; a proposal to waive in vivo bioequivalence requirements for WHO Model List of Essential Medicines immediate-release, solid oral WHO dosage forms; and additional guidance for organizations Technical performing in vivo bioequivalence studies.