Spatial Frames of Reference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Mechanics

Classical Mechanics Hyoungsoon Choi Spring, 2014 Contents 1 Introduction4 1.1 Kinematics and Kinetics . .5 1.2 Kinematics: Watching Wallace and Gromit ............6 1.3 Inertia and Inertial Frame . .8 2 Newton's Laws of Motion 10 2.1 The First Law: The Law of Inertia . 10 2.2 The Second Law: The Equation of Motion . 11 2.3 The Third Law: The Law of Action and Reaction . 12 3 Laws of Conservation 14 3.1 Conservation of Momentum . 14 3.2 Conservation of Angular Momentum . 15 3.3 Conservation of Energy . 17 3.3.1 Kinetic energy . 17 3.3.2 Potential energy . 18 3.3.3 Mechanical energy conservation . 19 4 Solving Equation of Motions 20 4.1 Force-Free Motion . 21 4.2 Constant Force Motion . 22 4.2.1 Constant force motion in one dimension . 22 4.2.2 Constant force motion in two dimensions . 23 4.3 Varying Force Motion . 25 4.3.1 Drag force . 25 4.3.2 Harmonic oscillator . 29 5 Lagrangian Mechanics 30 5.1 Configuration Space . 30 5.2 Lagrangian Equations of Motion . 32 5.3 Generalized Coordinates . 34 5.4 Lagrangian Mechanics . 36 5.5 D'Alembert's Principle . 37 5.6 Conjugate Variables . 39 1 CONTENTS 2 6 Hamiltonian Mechanics 40 6.1 Legendre Transformation: From Lagrangian to Hamiltonian . 40 6.2 Hamilton's Equations . 41 6.3 Configuration Space and Phase Space . 43 6.4 Hamiltonian and Energy . 45 7 Central Force Motion 47 7.1 Conservation Laws in Central Force Field . 47 7.2 The Path Equation . -

Pioneers in Optics: Christiaan Huygens

Downloaded from Microscopy Pioneers https://www.cambridge.org/core Pioneers in Optics: Christiaan Huygens Eric Clark From the website Molecular Expressions created by the late Michael Davidson and now maintained by Eric Clark, National Magnetic Field Laboratory, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306 . IP address: [email protected] 170.106.33.22 Christiaan Huygens reliability and accuracy. The first watch using this principle (1629–1695) was finished in 1675, whereupon it was promptly presented , on Christiaan Huygens was a to his sponsor, King Louis XIV. 29 Sep 2021 at 16:11:10 brilliant Dutch mathematician, In 1681, Huygens returned to Holland where he began physicist, and astronomer who lived to construct optical lenses with extremely large focal lengths, during the seventeenth century, a which were eventually presented to the Royal Society of period sometimes referred to as the London, where they remain today. Continuing along this line Scientific Revolution. Huygens, a of work, Huygens perfected his skills in lens grinding and highly gifted theoretical and experi- subsequently invented the achromatic eyepiece that bears his , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at mental scientist, is best known name and is still in widespread use today. for his work on the theories of Huygens left Holland in 1689, and ventured to London centrifugal force, the wave theory of where he became acquainted with Sir Isaac Newton and began light, and the pendulum clock. to study Newton’s theories on classical physics. Although it At an early age, Huygens began seems Huygens was duly impressed with Newton’s work, he work in advanced mathematics was still very skeptical about any theory that did not explain by attempting to disprove several theories established by gravitation by mechanical means. -

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM and ROTATIONS

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM AND ROTATIONS In classical mechanics the total angular momentum L~ of an isolated system about any …xed point is conserved. The existence of a conserved vector L~ associated with such a system is itself a consequence of the fact that the associated Hamiltonian (or Lagrangian) is invariant under rotations, i.e., if the coordinates and momenta of the entire system are rotated “rigidly” about some point, the energy of the system is unchanged and, more importantly, is the same function of the dynamical variables as it was before the rotation. Such a circumstance would not apply, e.g., to a system lying in an externally imposed gravitational …eld pointing in some speci…c direction. Thus, the invariance of an isolated system under rotations ultimately arises from the fact that, in the absence of external …elds of this sort, space is isotropic; it behaves the same way in all directions. Not surprisingly, therefore, in quantum mechanics the individual Cartesian com- ponents Li of the total angular momentum operator L~ of an isolated system are also constants of the motion. The di¤erent components of L~ are not, however, compatible quantum observables. Indeed, as we will see the operators representing the components of angular momentum along di¤erent directions do not generally commute with one an- other. Thus, the vector operator L~ is not, strictly speaking, an observable, since it does not have a complete basis of eigenstates (which would have to be simultaneous eigenstates of all of its non-commuting components). This lack of commutivity often seems, at …rst encounter, as somewhat of a nuisance but, in fact, it intimately re‡ects the underlying structure of the three dimensional space in which we are immersed, and has its source in the fact that rotations in three dimensions about di¤erent axes do not commute with one another. -

A Guide to Space Law Terms: Spi, Gwu, & Swf

A GUIDE TO SPACE LAW TERMS: SPI, GWU, & SWF A Guide to Space Law Terms Space Policy Institute (SPI), George Washington University and Secure World Foundation (SWF) Editor: Professor Henry R. Hertzfeld, Esq. Research: Liana X. Yung, Esq. Daniel V. Osborne, Esq. December 2012 Page i I. INTRODUCTION This document is a step to developing an accurate and usable guide to space law words, terms, and phrases. The project developed from misunderstandings and difficulties that graduate students in our classes encountered listening to lectures and reading technical articles on topics related to space law. The difficulties are compounded when students are not native English speakers. Because there is no standard definition for many of the terms and because some terms are used in many different ways, we have created seven categories of definitions. They are: I. A simple definition written in easy to understand English II. Definitions found in treaties, statutes, and formal regulations III. Definitions from legal dictionaries IV. Definitions from standard English dictionaries V. Definitions found in government publications (mostly technical glossaries and dictionaries) VI. Definitions found in journal articles, books, and other unofficial sources VII. Definitions that may have different interpretations in languages other than English The source of each definition that is used is provided so that the reader can understand the context in which it is used. The Simple Definitions are meant to capture the essence of how the term is used in space law. Where possible we have used a definition from one of our sources for this purpose. When we found no concise definition, we have drafted the definition based on the more complex definitions from other sources. -

Energy Harvesters for Space Applications 1

Energy harvesters for space applications 1 Energy harvesters for space R. Graczyk limited, especially that they are likely to operate in charge Abstract—Energy harvesting is the fundamental activity in (energy build-up in span of minutes or tens of minutes) and almost all forms of space exploration known to humans. So far, act (perform the measurement and processing quickly and in most cases, it is not feasible to bring, along with probe, effectively). spacecraft or rover suitable supply of fuel to cover all mission’s State-of-the-art research facilitated by growing industrial energy needs. Some concepts of mining or other form of interest in energy harvesting as well as innovative products manufacturing of fuel on exploration site have been made, but they still base either on some facility that needs one mean of introduced into market recently show that described energy to generate fuel, perhaps of better quality, or needs some techniques are viable source of energy for sensors, sensor initial energy to be harvested to start a self sustaining cycle. networks and personal devices. Research and development Following paper summarizes key factors that determine satellite activities include technological advances for automotive energy needs, and explains some either most widespread or most industry (tire pressure monitors, using piezoelectric effect ), interesting examples of energy harvesting devices, present in Earth orbit as well as exploring Solar System and, very recently, aerospace industry (fuselage sensor network in aircraft, using beyond. Some of presented energy harvester are suitable for thermoelectric effect), manufacturing automation industry very large (in terms of size and functionality) probes, other fit (various sensors networks, using thermoelectric, piezoelectric, and scale easily on satellites ranging from dozens of tons to few electrostatic, photovoltaic effects), personal devices (wrist grams. -

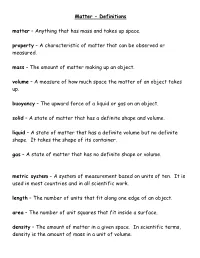

Definitions Matter – Anything That Has Mass and Takes up Space. Property – a Characteristic of Matter That Can Be Observed Or Measured

Matter – Definitions matter – Anything that has mass and takes up space. property – A characteristic of matter that can be observed or measured. mass – The amount of matter making up an object. volume – A measure of how much space the matter of an object takes up. buoyancy – The upward force of a liquid or gas on an object. solid – A state of matter that has a definite shape and volume. liquid – A state of matter that has a definite volume but no definite shape. It takes the shape of its container. gas – A state of matter that has no definite shape or volume. metric system – A system of measurement based on units of ten. It is used in most countries and in all scientific work. length – The number of units that fit along one edge of an object. area – The number of unit squares that fit inside a surface. density – The amount of matter in a given space. In scientific terms, density is the amount of mass in a unit of volume. weight – The measure of the pull of gravity between an object and Earth. gravity – A force of attraction, or pull, between objects. physical change – A change that begins and ends with the same type of matter. change of state – A physical change of matter from one state – solid, liquid, or gas – to another state because of a change in the energy of the matter. evaporation – The process of a liquid changing to a gas. rust – A solid brown compound formed when iron combines chemically with oxygen. chemical change – A change that produces new matter with different properties from the original matter. -

On Space-Time, Reference Frames and the Structure of Relativity Groups Annales De L’I

ANNALES DE L’I. H. P., SECTION A VITTORIO BERZI VITTORIO GORINI On space-time, reference frames and the structure of relativity groups Annales de l’I. H. P., section A, tome 16, no 1 (1972), p. 1-22 <http://www.numdam.org/item?id=AIHPA_1972__16_1_1_0> © Gauthier-Villars, 1972, tous droits réservés. L’accès aux archives de la revue « Annales de l’I. H. P., section A » implique l’accord avec les conditions générales d’utilisation (http://www.numdam. org/conditions). Toute utilisation commerciale ou impression systématique est constitutive d’une infraction pénale. Toute copie ou impression de ce fichier doit contenir la présente mention de copyright. Article numérisé dans le cadre du programme Numérisation de documents anciens mathématiques http://www.numdam.org/ Ann. Inst. Henri Poincaré, Section A : Vol. XVI, no 1, 1972, 1 Physique théorique. On space-time, reference frames and the structure of relativity groups Vittorio BERZI Istituto di Scienze Fisiche dell’ Universita, Milano, Italy, Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Sezione di Milano, Italy Vittorio GORINI (*) Institut fur Theoretische Physik (I) der Universitat Marburg, Germany ABSTRACT. - A general formulation of the notions of space-time, reference frame and relativistic invariance is given in essentially topo- logical terms. Reference frames are axiomatized as C° mutually equi- valent real four-dimensional C°-atlases of the set M denoting space- time, and M is given the C°-manifold structure which is defined by these atlases. We attempt ti give an axiomatic characterization of the concept of equivalent frames by introducing the new structure of equiframe. In this way we can give a precise definition of space-time invariance group 2 of a physical theory formulated in terms of experi- ments of the yes-no type. -

An Artificial Gravity Space Station at the Earth-Moon L1 Point

Clarke Station: An Artificial Gravity Space Station at the Earth-Moon L1 Point University of Maryland, College Park Department of Aerospace Engineering Undergraduate Program Matthew Ashmore, Daniel Barkmeyer, Laurie Daddino, Sarah Delorme, Dominic DePasquale, Joshua Ellithorpe, Jessica Garzon, Jacob Haddon, Emmie Helms, Raquel Jarabek, Jeffrey Jensen, Steve Keyton, Aurora Labador, Joshua Lyons, Bruce Macomber Jr., Aaron Nguyen, Larry O'Dell, Brian Ross, Cristin Sawin, Matthew Scully, Eric Simon, Kevin Stefanik, Daniel Sutermeister, Bruce Wang Advisors: Dr. David Akin, Dr. Mary Bowden Abstract In order to perform deep space life sciences and artificial gravity research, a 315 metric ton space station has been designed for the L1 libration point between the Earth and the Moon. The station provides research facilities for a total of eight crew in two habitats connected to their center of rotation by 68 m trusses. A third mass is offset for stability. Solar arrays and docking facilities are contained on the axis perpendicular to rotation. A total of 320 m2 of floor space at gravity levels from microgravity to 1.2g’s are available for research and experimentation. Specific research capabilities include radiation measurement and testing, human physiological adaptation measurement, and deep space manned mission simulation. Introduction Space is a harsh and unforgiving environment. In addition to basic life support requirements, radiation exposure, cardiovascular deconditioning, muscle atrophy, and skeletal demineralization represent major hazards associated with human travel and habitation in deep space. All of these hazards require special attention and prevention for a successful mission to Mars or a long duration return to the Moon. Greater knowledge of human physical response to the deep space environment and reduced gravity is required to develop safe prevention methods. -

3. Translational and Rotational Dynamics MAE 345 2017.Pptx

Translational and Rotational Dynamics! Robert Stengel! Robotics and Intelligent Systems MAE 345, Princeton University, 2017 Copyright 2017 by Robert Stengel. All rights reserved. For educational use only. http://www.princeton.edu/~stengel/MAE345.html 1 Reference Frame •! Newtonian (Inertial) Frame of Reference –! Unaccelerated Cartesian frame •! Origin referenced to inertial (non-moving) frame –! Right-hand rule –! Origin can translate at constant linear velocity –! Frame cannot rotate with respect to inertial origin ! x $ # & •! Position: 3 dimensions r = # y & –! What is a non-moving frame? "# z %& •! Translation = Linear motion 2 Velocity and Momentum of a Particle •! Velocity of a particle ! $ ! x! $ vx dr # & # & v = = r! = y! = # vy & dt # & # ! & # & " z % vz "# %& •! Linear momentum of a particle ! v $ # x & p = mv = m # vy & # & "# vz %& 3 Newtons Laws of Motion: ! Dynamics of a Particle First Law . If no force acts on a particle, it remains at rest or continues to move in straight line at constant velocity, . Inertial reference frame . Momentum is conserved d ()mv = 0 ; mv = mv dt t1 t2 4 Newtons Laws of Motion: ! Dynamics of a Particle Second Law •! Particle acted upon by force •! Acceleration proportional to and in direction of force •! Inertial reference frame •! Ratio of force to acceleration is particle mass d dv dv 1 1 ()mv = m = ma = Force ! = Force = I Force dt dt dt m m 3 ! $ " % fx " % fx # & 1/ m 0 0 $ ' = $ ' f Force = # fy & = force vector $ 0 1/ m 0 '$ y ' $ ' # & #$ 0 0 1/ m &' f fz $ z ' "# %& # & 5 Newtons Laws -

PHASE SPACE 1. Phase Space in Physics, Phase Space Is a Concept

PHASE SPACE TERENCE TAO 1. Phase space In physics, phase space is a concept which unifies classical (Hamiltonian) mechanics and quantum mechanics; in mathematics, phase space is a concept which unifies symplectic geometry with harmonic analysis and PDE. In classical mechanics, the phase space is the space of all possible states of a physical system; by “state” we do not simply mean the positions q of all the objects in the system (which would occupy physical space or configuration space), but also their velocities or momenta p (which would occupy momentum space). One needs both the position and momentum of system in order to determine the future behavior of that system. Mathematically, the configuration space might be defined by a manifold M (either finite1 or infinite dimensional), and for each position q ∈ M in that space, the momentum p of the system would take values in the cotangent2 ∗ space Tq M of that space. Thus phase space is naturally represented here by the ∗ ∗ cotangent bundle T M := {(q, p): q ∈ M, p ∈ Tq M}, which comes with a canonical symplectic form ω := dp ∧ dq. Hamilton’s equation of motion describe the motion t 7→ (q(t), p(t)) of a system in phase space as a function of time in terms of a Hamiltonian H : M → R, by Hamilton’s equations of motion d ∂H d ∂H q(t) = (q(t), p(t)); p(t) = − (q(t), p(t)), dt ∂p dt ∂q or equivalently in terms of the symplectic form ω as x˙(t) = ∇ωH(x(t)), where x(t) := (q(t), p(t)) is the trajectory of the system in phase space, and ∇ω is the symplectic gradient, thus ω(·, ∇ωH) = dH. -

Chapter 19 Angular Momentum

Chapter 19 Angular Momentum 19.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 19.2 Angular Momentum about a Point for a Particle .............................................. 2 19.2.1 Angular Momentum for a Point Particle ..................................................... 2 19.2.2 Right-Hand-Rule for the Direction of the Angular Momentum ............... 3 Example 19.1 Angular Momentum: Constant Velocity ........................................ 4 Example 19.2 Angular Momentum and Circular Motion ..................................... 5 Example 19.3 Angular Momentum About a Point along Central Axis for Circular Motion ........................................................................................................ 5 19.3 Torque and the Time Derivative of Angular Momentum about a Point for a Particle ........................................................................................................................... 8 19.4 Conservation of Angular Momentum about a Point ......................................... 9 Example 19.4 Meteor Flyby of Earth .................................................................... 10 19.5 Angular Impulse and Change in Angular Momentum ................................... 12 19.6 Angular Momentum of a System of Particles .................................................. 13 Example 19.5 Angular Momentum of Two Particles undergoing Circular Motion ..................................................................................................................... -

NATIONAL SPACE POLICY of the UNITED STATES of AMERICA

NATIONAL SPACE POLICY of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DECEMBER 9, 2020 “We are a nation of pioneers. We are the people who crossed the ocean, carved out a foothold on a vast continent, settled a great wilderness, and then set our eyes upon the stars. This is our history, and this is our destiny.” President Donald J. Trump Kennedy Space Center May 30, 2020 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Principles ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Goals ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Cross Sector Guidelines ............................................................................................................................. 7 Foundational Activities and Capabilities .................................................................................................. 7 International Cooperation ...................................................................................................................... 12 Preserving the Space Environment to Enhance the Long-term Sustainability of Space Activities ......... 14 Effective Export Policies .........................................................................................................................