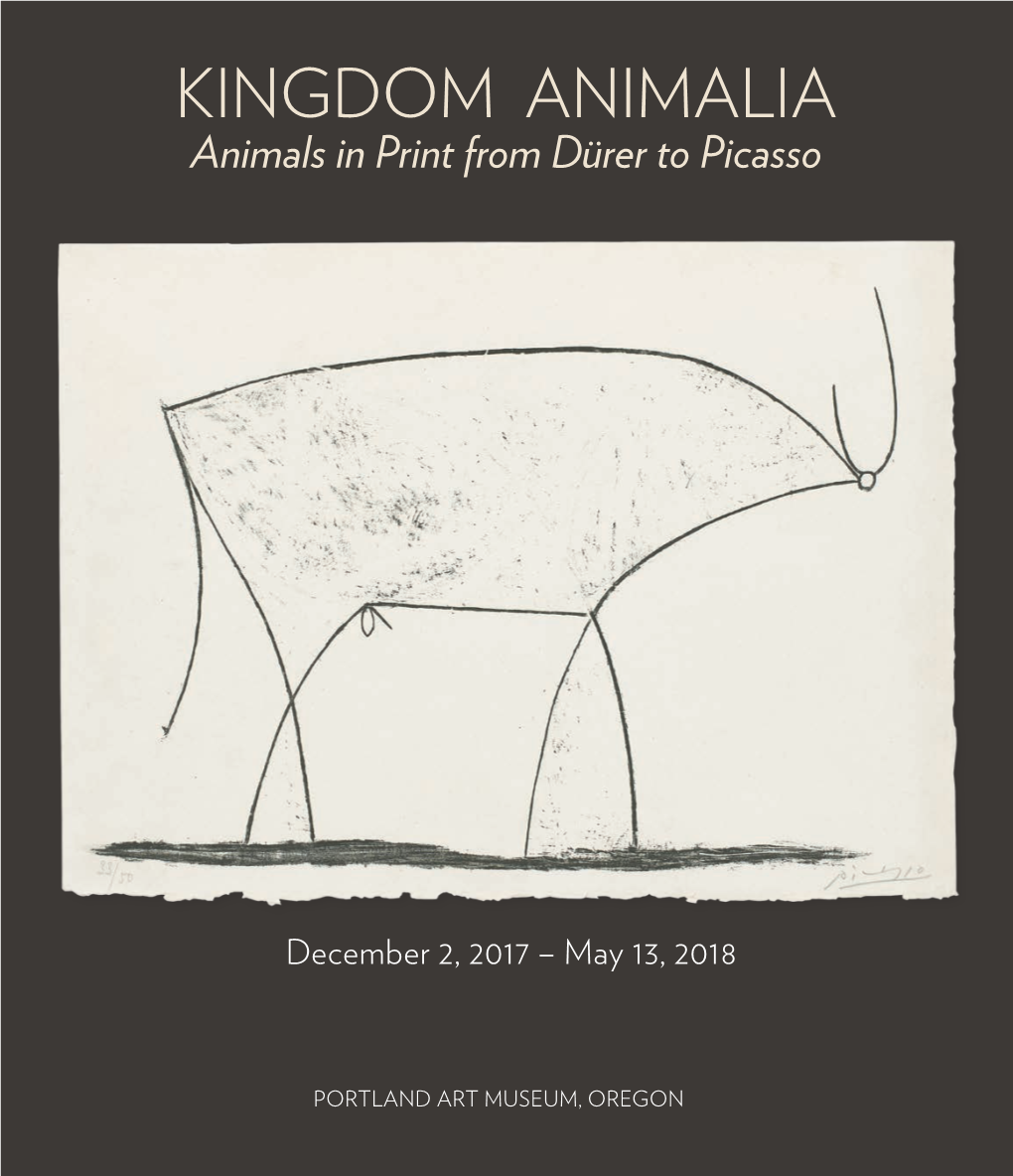

Kingdom Animalia: Animals in Print from Dürer to Picasso

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amanda Snyder Portland Modernist

BONNIE LAING-MALCOLMSON Amanda Snyder Portland Modernist PORTLAND ART MUSEUM OREGON Contents 9 Director’s Foreword Brian J. Ferriso 13 A Portland Modernist Bonnie Laing-Malcolmson Published on the occasion of the exhibition Amanda Snyder: Portland Modernist, Organized by the Portland Art Museum, Oregon, June 30 – October 7, 2012. 44 Biography This publication is made possible by a generous bequest of Eugene E. Snyder. Copyright © 2012 Portland Art Museum, Oregon All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the 49 Checklist of Exhibition written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. Amanda Snyder: Portland Modernist p. 58; cm Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR. June 30 – October 7, 2012 Includes exhibition checklist, artist biography, and illustrations ISBN 9781883124344 Published by Portland Art Museum 1219 SW Park Avenue Portland, Oregon 97205 Publication coordinator: Bruce Guenther Design: Bryan Potter Design Photography: Paul Foster Printed: Image Pressworks, Portland Director’s Foreword With the opening of The Arlene and Harold Schnitzer Center for Northwest Art in 2000, and the subsequent establishment of a permanently endowed Curator of Northwest Art in 2006, the Portland Art Museum signaled its intention to create an historical record of our artistic community and its participants through an active exhibition, collection, and publication program. This commitment has resulted in the creation of an ongoing one-person contemporary exhibition series for artists of our region, APEX, and the biennial Contemporary Northwest Art Awards, as well as a renewed focus on historic figures through landmark survey exhibitions like Hilda Morris and Lee Kelly. -

AQUATINT: OPENING TIMES: Monday - Friday: 9:30 -18:30 PRINTING in SHADES Saturday - Sunday: 12:00 - 18:00

A Q U A T I N T : P R I N T I N G I N S H A D E S GILDEN’S ARTS GALLERY 74 Heath Street Hampstead Village London NW3 1DN AQUATINT: OPENING TIMES: Monday - Friday: 9:30 -18:30 PRINTING IN SHADES Saturday - Sunday: 12:00 - 18:00 GILDENSARTS.COM [email protected] +44 (0)20 7435 3340 G I L D E N ’ S A R T S G A L L E R Y GILDEN’S ARTS GALLERY AQUATINT: PRINTING IN SHADES April – June 2015 Director: Ofer Gildor Text and Concept: Daniela Boi and Veronica Czeisler Gallery Assistant: Costanza Sciascia Design: Steve Hayes AQUATINT: PRINTING IN SHADES In its ongoing goal to research and promote works on paper and the art of printmaking, Gilden’s Arts Gallery is glad to present its new exhibition Aquatint: Printing in Shades. Aquatint was first invented in 1650 by the printmaker Jan van de Velde (1593-1641) in Amsterdam. The technique was soon forgotten until the 18th century, when a French artist, Jean Baptiste Le Prince (1734-1781), rediscovers a way of achieving tone on a copper plate without the hard labour involved in mezzotint. It was however not in France but in England where this technique spread and flourished. Paul Sandby (1731 - 1809) refined the technique and coined the term Aquatint to describe the medium’s capacity to create the effects of ink and colour washes. He and other British artists used Aquatint to capture the pictorial quality and tonal complexities of watercolour and painting. -

Guide to Oral History Collections in Missouri

Guide to Oral History Collections in Missouri. Compiled and Edited by David E. Richards Special Collections & Archives Department Duane G. Meyer Library Missouri State University Springfield, Missouri Last updated: September 16, 2012 This guide was made possible through a grant from the Richard S. Brownlee Fund from the State Historical Society of Missouri and support from Missouri State University. Introduction Missouri has a wealth of oral history recordings that document the rich and diverse population of the state. Beginning around 1976, libraries, archives, individual researchers, and local historical societies initiated oral history projects and began recording interviews on audio cassettes. The efforts continued into the 1980s. By 2000, digital recorders began replacing audio cassettes and collections continued to grow where staff, time, and funding permitted. As with other states, oral history projects were easily started, but transcription and indexing efforts generally lagged behind. Hundreds of recordings existed for dozens of discreet projects, but access to the recordings was lacking or insufficient. Larger institutions had the means to transcribe, index, and catalog their oral history materials, but smaller operations sometimes had limited access to their holdings. Access was mixed, and still is. This guide attempts to aggregate nearly all oral history holdings within the state and provide at least basic, minimal access to holdings from the largest academic repository to the smallest county historical society. The effort to provide a guide to the oral history collections of Missouri started in 2002 with a Brownlee Fund Grant from the State Historical Society of Missouri. That initial grant provided the seed money to create and send out a mail-in survey. -

Goya: Monstruos, Sueno Y Razon

GOYA: MONSTRUOS, SUEÑO Y RAZÓN • � Goya: Monstruos, --1 sueno- y razon,, eo' ROXANA FOLADORI ANTúNEZ 5 GOYA EN EL ESCENARIO n Sevilla a fines de 1792, el pintor Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, a sus 46 Eaños de edad, es preso de un misterioso padecimiento, que le provocó una sordera absoluta que perduraría los 40 años restantes de su vida. Su trabajo en lugar de cesar, debido a los impedimentos que pudiese representar su irremediable padecimiento, se intensifica a partir de esa fecha. Debido a sus méritos y reconocimiento, le son encargados una cantidad inmensa de retratos como: "La Duquesa de Alba" en 1795 y en 1797, "Juan López" y "Ascencio Juliá" en 1798, "La Reina María Luisa" y "Carlos IV' en 1799, "Condesa de Chichón" y "Familia de Carlos IV' en 1800, "Godoy" en 1801, "Marquesa de Santa Cruz" en 1805; "Fernando VII" en 1808, "Palafox" 1814. En 1815 retrata al "Duque de San Carlos", a "Fray Juan Fernández de Rojas", y a "Rafael Esteve"; en 1816 a "El Duque de Osuna", y a la "Duquesa de Abrantes"; en 1820 al "Doctor Arrieta"; en 1827 a "Juan Bautista de Muguiro" y a "José Pío de Malina". También durante el periodo de su sordera, le son encomendados trabajos en lugares públicos como la Santa Cueva de Cádiz, 1795; "Milagro de San Antonio de Padua" en San Antonio de la Florida, Madrid en 1798; "La Asunción de la Virgen" en la iglesia de Chichón; 1819, "La última comunión de San José de Calasanz" en la iglesia de los Escolapios de San Antón en Madrid. -

2013 Financial Statements and Report of Independent Accountants

GaryMcGee & Co. LLP CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS Portland Art Museum Financial Statements and Other Information as of and for the Years Ended June 30, 2013 and 2012 and Report of Independent Accountants P O R T L A N D A R T M U S E U M TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Report of the Treasurer 3 Report of Independent Accountants 4 Financial Statements: Statements of Financial Position 6 Statements of Activities 8 Statements of Cash Flows 10 Notes to Financial Statements 11 Supplementary Financial Information: Schedule of Operating Revenues and Expenses of the Northwest Film Center 30 Notes to Schedule of Operating Revenues and Expenses of the Northwest Film Center 31 Other Information: Governing Board and Management 32 Inquiries and Other Information 34 Report of the Treasurer The financial statements and other information con- The financial statements have been examined by the tained in this report have been prepared by manage- Museum’s independent accountants, GARY MCGEE & ment, which is responsible for the information’s integ- CO. LLP, whose report follows. Their examinations rity and objectivity. The financial statements have were made in accordance with generally accepted au- been prepared in accordance with generally accepted diting standards. The Audit Committee of the Board accounting principles applied on a consistent basis and of Trustees meets periodically with management and are deemed to present fairly the financial position of the independent accountants to review accounting, the PORTLAND ART MUSEUM and the changes in its net auditing, internal accounting controls, and financial assets and cash flows. Where necessary, management reporting matters, and to ensure that all responsibili- has made informed judgments and estimates of the ties are fulfilled with regard to the objectivity and in- outcome of events and transactions, with due consid- tegrity of the Museum’s financial statements. -

The Dark Romanticism of Francisco De Goya

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 The shadow in the light: The dark romanticism of Francisco de Goya Elizabeth Burns-Dans The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Burns-Dans, E. (2018). The shadow in the light: The dark romanticism of Francisco de Goya (Master of Philosophy (School of Arts and Sciences)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/214 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i DECLARATION I declare that this Research Project is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which had not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. Elizabeth Burns-Dans 25 June 2018 This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence. i ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the enduring support of those around me. Foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Deborah Gare for her continuous, invaluable and guiding support. -

How to Quote Voltaire: the Edition to Use1 February 2021

How to quote Voltaire: the edition to use1 February 2021 A complete alphabetical list of Voltaire texts and in which edition and volume to find them. The Voltaire Foundation’s Œuvres complètes de Voltaire (OCV) edition includes most texts, but for those not yet published in OCV, the 1877-1885 Moland edition (M) is mostly given. Abbreviations used AP Ajouts posthumes Best., followed by a a letter printed in Voltaire’s correspondence, ed. Th. Besterman, number 107 vol. (Geneva, 1953-1965, 1st edition) BnC Bibliothèque nationale de France: Catalogue général des livres imprimés, 213-214 (1978) BnF, ms.fr. Bibliothèque nationale de France: Manuscrits français BnF, n.a.fr. Bibliothèque nationale de France: Nouvelles acquisitions françaises D, followed by a number a letter printed in Voltaire, Correspondence and related documents, ed. Th. Besterman, in OCV, vol.85-135 DP Dictionnaire philosophique Lizé Voltaire, Grimm et la Correspondence littéraire, SVEC 180 (1979) M Œuvres complètes de Voltaire, éd. Louis Moland, 52 vol. (Paris, Garnier, 1877-1885) NM Nouveaux Mélanges philosophiques, historiques, critiques ([Genève], 1768) OA Œuvres alphabétiques (Articles pour l’Encyclopédie, Articles pour le Dictionnaire de l’Académie) OCV Œuvres complètes de Voltaire (Voltaire Foundation, Oxford, 1968- ) QE Questions sur l’Encyclopédie RC Romans et Contes, ed. Frédéric Deloffre et Jacques van den Heuvel (Paris, Gallimard [Pléiade], 1979) RHLF Revue d’histoire littéraire de la France (Presses universitaire de France) SVEC Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century (Voltaire Foundation) Vauger ‘Vauger’s lists of Voltaire’s writings, 1757-1785’ (D.app.161, OCV, vol.102, p.509-10) W72P Œuvres de M. -

Private Collection of Camille Pissarro Works Featured in Swann Galleries’ Old Master-Modern Sale

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Alexandra Nelson October 14, 2016 Communications Director 212-254-4710 ext. 19 [email protected] Private Collection of Camille Pissarro Works Featured in Swann Galleries’ Old Master-Modern Sale New York— On Thursday, November 3, Swann Galleries will hold an auction of Old Master Through Modern Prints, featuring section of the sale devoted to a collection works by Camille Pissarro: Impressionist Icon. The beginning of the auction offers works by renowned Old Masters, with impressive runs by Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt van Rijn. Scarce engravings by Dürer include his 1514 Melencholia I, a well-inked impression estimated at $70,000 to $100,000, and Knight, Death and the Devil, 1513 ($60,000 to $90,000), as well as a very scarce chiaroscuro woodcut of Ulrich Varnbüler, 1522 ($40,000 to $60,000). Rembrandt’s etching, engraving and drypoint Christ before Pilate: Large Plate, 1635-36, is estimated at $60,000 to $90,000, while one of earliest known impressions of Cottages Beside a Canal: A View of Diemen, circa 1645, is expected to sell for $50,000 to $80,000. The highlight of the sale is a private collection of prints and drawings by Impressionist master Camille Pissarro. This standalone catalogue surveys Impressionism’s most prolific printmaker, and comprises 67 lots of prints and drawings, including many lifetime impressions that have rarely been seen at auction. One of these is Femme vidant une brouette, 1880, a scarce etching and drypoint of which fewer than thirty exist. Only three other lifetime impressions have appeared at auction; this one is expected to sell for $30,000 to $50,000. -

Voltaire Et Le Sauvage Civilisé

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2010 Voltaire et le sauvage civilisé Christopher J. Barros San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Barros, Christopher J., "Voltaire et le sauvage civilisé" (2010). Master's Theses. 3747. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.883s-xa8q https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3747 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLTAIRE ET LE « SAUVAGE CIVILISÉ » A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of World Languages and Literatures San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Master of Arts by Christopher J. Barros May 2010 © 2010 Christopher J. Barros ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled VOLTAIRE ET LE « SAUVAGE CIVILISÉ » by Christopher Joseph Barros APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF WORLD LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY May 2010 Danielle Trudeau Department of World Languages and Literatures Jean-Luc Desalvo Department of World Languages and Literatures Dominique van Hooff Department of World Languages and Literatures ABSTRACT VOLTAIRE ET LE « SAUVAGE CIVILISÉ » by Christopher J. Barros This thesis explores Voltaire’s interpretation of human nature, society, and progress vis-à-vis the myth of the “noble savage,” an image that was widespread in the literature, imagination, and theater of the 17th and 18th centuries. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Voltaire's Candide

CANDIDE Voltaire 1759 © 1998, Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project http://www.esp.org This electronic edition is made freely available for scholarly or educational purposes, provided that this copyright notice is included. The manuscript may not be reprinted or redistributed for commercial purposes without permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1.....................................................................................1 How Candide Was Brought Up in a Magnificent Castle and How He Was Driven Thence CHAPTER 2.....................................................................................3 What Befell Candide among the Bulgarians CHAPTER 3.....................................................................................6 How Candide Escaped from the Bulgarians and What Befell Him Afterward CHAPTER 4.....................................................................................8 How Candide Found His Old Master Pangloss Again and What CHAPTER 5...................................................................................11 A Tempest, a Shipwreck, an Earthquake, and What Else Befell Dr. Pangloss, Candide, and James, the Anabaptist CHAPTER 6...................................................................................14 How the Portuguese Made a Superb Auto-De-Fe to Prevent Any Future Earthquakes, and How Candide Underwent Public Flagellation CHAPTER 7...................................................................................16 How the Old Woman Took Care Of Candide, and How He Found the Object of -

A Finding Aid to the Adolf Dehn Papers, 1912-1987, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Adolf Dehn Papers, 1912-1987, in the Archives of American Art Kathleen Brown Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art January 21, 2009 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1920-1968..................................................... 6 Series 2: Correspondence, circa 1919-1982............................................................ 7 Series 3: Writings, circa 1920-1971......................................................................