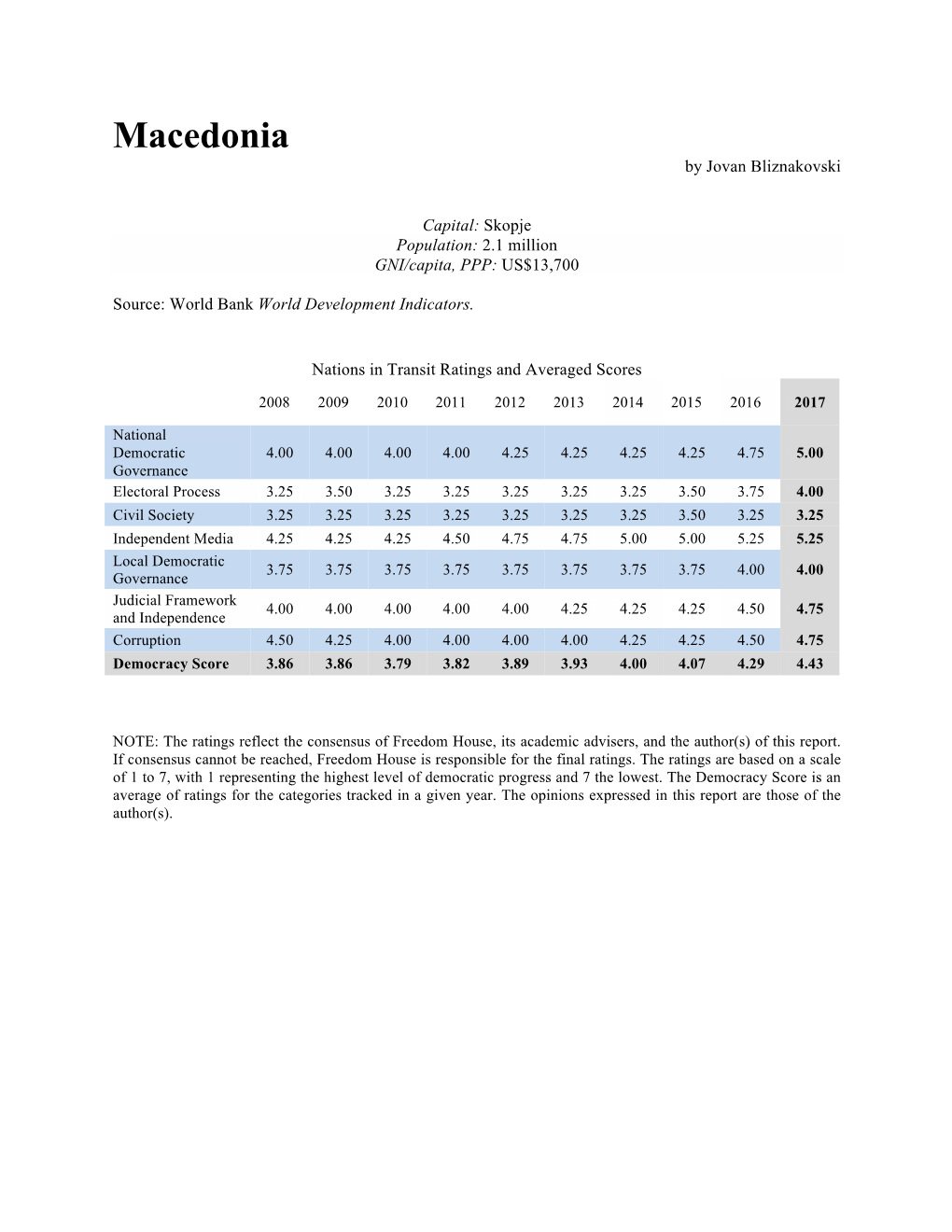

Macedonia by Jovan Bliznakovski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neuer Nationalismus Im Östlichen Europa

Irene Götz, Klaus Roth, Marketa Spiritova (Hg.) Neuer Nationalismus im östlichen Europa Ethnografische Perspektiven auf das östliche Europa Band 3 Editorial Die tiefgreifenden Transformationsprozesse, die die Gesellschaften des östli- chen Europas seit den letzten Jahrzehnten prägen, werden mit Begriffen wie Postsozialismus, Globalisierung und EU-Integration nur oberflächlich be- schrieben. Ethnografische Ansätze vermögen es, die damit einhergehenden Veränderungen der Alltage, Biografien und Identitäten multiperspektivisch und subjektorientiert zu beleuchten. Die Reihe Ethnografische Perspektiven auf das östliche Europa gibt vertiefte Einblicke in die Verflechtungen von ma- krostrukturellen Politiken und ihren medialen Repräsentationen mit den Prak- tiken der Akteurinnen und Akteure in urbanen wie ländlichen Lebenswelten. Themenfelder sind beispielsweise identitätspolitische Inszenierungen, Prozes- se des Nation Building, privates und öffentliches Erinnern, neue soziale Bewe- gungen und transnationale Mobilitäten in einer sich umgestaltenden Bürger- kultur. Die Reihe wird herausgegeben von Prof. Dr. Irene Götz, Professorin für Euro- päische Ethnologie an der LMU München. Irene Götz, Klaus Roth, Marketa Spiritova (Hg.) Neuer Nationalismus im östlichen Europa Kulturwissenschaftliche Perspektiven Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (BY). Diese Lizenz erlaubt unter Voraussetzung der Namensnennung des Urhebers die Bearbeitung, Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung des Materials in jedem For- mat oder Medium für -

Objet Petit A,” Once Socialist-Modernist City Square Into a Theatrical Backdrop

She just goes a little mad sometimes. We all go a little mad sometimes. Haven’t you? – Norman Bates in Psycho This essay is an galma dedicated to the Macedonian government’s project “Skopje 2014,” 01/09 which recently turned Skopje, the capital of the Republic, into a memorial park of “false memories.”1 Over the last five years, a series of unskillfully casted figurative monuments have appeared throughout Skopje, installed over the night, as if brought into public space by the animated hand from the opening credits of Monty Python’s Flying Circus.2 Figures from the Suzana Milevska national past (some relevant, some marginal), buildings with obvious references to Westernized aesthetic regimes (mere imitations of styles from çgalma: The periods atypical for the local architecture), and sexist public sculptures have transformed the ‟Objet Petit a,” once socialist-modernist city square into a theatrical backdrop. Alexander the ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊMore than ninety years ago, in a kind of a manifesto of anti-monumental architectural and artistic revolution, Vladimir Tatlin challenged 4 Great, and 1 both the “bourgeois” Eiffel Tower and the Statue 0 2 of Liberty with his unbuilt tower Monument to the e j p Third International (1919–25). Since then, Other Excesses o k S discourses on contemporary monuments have f o flourished elsewhere in Europe (“anti- s of Skopje 2014 e monuments,” “counter-monuments,” “low- s s e budget monuments,” “invisible monuments,” c x E “monument in waiting,” “participatory r 3 e monuments” ) but this debate has completely h t O a bypassed the Macedonian establishment. k d s n v ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊThe government’s promise that the Skopje a e l , i t 2014 project would attract tourists and a M e a r journalists to Macedonia has been realized, but n G a e z for all the wrong reasons – in many articles, h u t S r Ê Skopje’s city center is depicted as a kind of e 4 d 1 “theme park,” and some of the newly built n 0 a 2 x r museums are referred to as “chambers of e l e 4 b A horrors.” In short, Skopje 2014 has become a m ” , e a t laughing stock for the foreign press. -

Populism and Progressive Social Movements in Macedonia: from Rhetorical Trap to Discursive Asset*

164 POLITOLOGICKÝ ČASOPIS / CZECH JOURNAL OF POLITICAL SCIENCE 2/2016 Populism and Progressive Social Movements in Macedonia: From Rhetorical Trap to Discursive Asset* LJUPCHO PETKOVSKI AND DIMITAR NIKOLOVSKI** Abstract Since 2009, Macedonia has experienced the two largest waves of progressive civic activism in post-socialist times. In the 2009–2012 period, smaller groups of citizens rallied around issues as different as protection of public spaces, police brutality, rising prices of electricity, etc. Yet, it was not before the larger student mobilizations took place in 2014 that the social space significantly opened up with a number of social groups protesting the increasingly authoritarian rule of the il- liberal incumbents. In this paper, we investigate and compare the discursive strategies of the social movements (SM) in the two periods, especially the shift from ‘anti-populist rhetorical trap’ from the first period to the broader appeals for solidarity and a construction of equivalences which charac- terized the second period. In so doing, we hypothesize and demonstrate that the relative success in the second period can be accounted for in terms of the more inclusive discourse which helped SM avoid the ‘anti-populist trap’, thus challenging illiberal populism with progressive and (formally) populist discourse. Theoretically, the analysis goes back and forth between two approaches to stud- ying populism: the dominant theory which sees populism as democratic illiberalism and Laclau’s theory of hegemony that sees populism as a formal political logic with no predetermined ideological content. Keywords: Macedonia; populism; social movements; anti-populist rhetorical trap DOI: 10.5817/PC2016-2-164 1. Introduction Since 2009, Macedonia has experienced the two largest waves of progressive civic activism in post-socialist times. -

General Elections in Macédonia 5Th June 2011

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN MACEDONIA 5th june 2011 European Elections monitor Four months of Parliamentary boycott by the opposition lead Nikola Gruevski to convene early Corinne Deloy general elections in Macedonia Translated by Helen Levy On 15th April the Sobranie, the only Chamber of Parliament in Macedonia, was dissolved by 79 of the ANALYSIS 120 MPs and early general elections were convened for 5th June by Macedonian Prime Minister Nikola 1 month before Gruevski (Revolutionary Organisation-Democratic Party for National Unity (VMRO-DPMNE). According the poll to the electoral law the election has to be organised within 60 days following dissolution. This decision follows the political crisis that Macedonia has been experiencing since the beginning of 2011. An early election after political crisis The VMRO-DPMN qualified the opposition forces decision “as a crime contrary to the interests of Macedonia and Indeed since 28th January the opposition forces – the its perspective for a European future.” “The irresponsible Social Democratic Union, SDSM and the Albanian Demo- behaviour of some politicians may ruin the results that cratic Party, PDA-PDSh (i.e. 38 MPs in all) – decided to we have achieved,” declared parliament’s spokesperson boycott the sessions of Parliament in protest against the Trajko Veljanovski who denounced the ‘artificial political freezing of the bank accounts of media tycoon Velij Aram- crisis’ created by the opposition parties. kovski, owner of the TV channel A1 and the newspapers The SDSM which indicated that it would not give up its Vreme, Shpic and E Re. Velij Aramkovski was arrested with boycott of Parliament announced that it would take part 16 of his employees in December 2010; he is accused of in the next general elections. -

Download (515Kb)

European Community No. 26/1984 July 10, 1984 Contact: Ella Krucoff (202) 862-9540 THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT: 1984 ELECTION RESULTS :The newly elected European Parliament - the second to be chosen directly by European voters -- began its five-year term last month with an inaugural session in Strasbourg~ France. The Parliament elected Pierre Pflimlin, a French Christian Democrat, as its new president. Pflimlin, a parliamentarian since 1979, is a former Prime Minister of France and ex-mayor of Strasbourg. Be succeeds Pieter Dankert, a Dutch Socialist, who came in second in the presidential vote this time around. The new assembly quickly exercised one of its major powers -- final say over the European Community budget -- by blocking payment of a L983 budget rebate to the United Kingdom. The rebate had been approved by Community leaders as part of an overall plan to resolve the E.C.'s financial problems. The Parliament froze the rebate after the U.K. opposed a plan for covering a 1984 budget shortfall during a July Council of Ministers meeting. The issue will be discussed again in September by E.C. institutions. Garret FitzGerald, Prime Minister of Ireland, outlined for the Parliament the goals of Ireland's six-month presidency of the E.C. Council. Be urged the representatives to continue working for a more unified Europe in which "free movement of people and goods" is a reality, and he called for more "intensified common action" to fight unemployment. Be said European politicians must work to bolster the public's faith in the E.C., noting that budget problems and inter-governmental "wrangles" have overshadolted the Community's benefits. -

Digging in Kitsch Depths

Digging in Kitsch Depths Uncovering Urban Development Projects Skopje 2014 - Inverdan Iris Verschuren Erasmus Mundus Master Course in Urban Studies 4 Cities Academic Year of Defence: 2017-2018 Date of Submission: September 1, 2017 Supervisors Martin Zerlang, Henrik Reeh Second Reader Bas van Heur Abstract This research concerns itself with forms of kitsch in two urban development projects. These projects in Skopje, Macedonia and Zaandam, The Netherlands, are discussed in their specific contexts and then analysed along a framework based on themes and topics related to the cultural category of kitsch. This category deals with both stylistic and aesthetic characteristics, but also focuses on processes outside of the object. Thus it enables to think of kitsch as a label that can just as well be applied to politics, policies or therefore urban development projects apart from just cultural objects. Furthermore linking kitsch with the ideologies and narratives of the UDPs shows how these are expressed in the actual physical form. In the end it is about the question what labeling these projects kitsch means, but also in what ways the label is used or applied and what kind of responses this evokes thus answering ‘in what ways can kitsch be related to the contemporary urban development projects Skopje 2014 and Inverdan?’ Although the cities and projects are incredibly different in context and the resulting style, there are still similarities in the way that kitsch is used and how this relates to a continuing global pressure to compete in neoliberal -

Download Article

5 Comment & Analysis CE JISS 2008 Czech Presidential Elections: A Commentary Petr Just Again after fi ve years, the attention of the Czech public and politicians was focused on the Presidential elections, one of the most important milestones of 2008 in terms of Czech political developments. The outcome of the last elections in 2003 was a little surprising as the candidate of the Civic Democratic Party (ODS), Václav Klaus, represented the opposition party without the necessary majority in both houses of Parliament. Instead, the ruling coalition of the Czech Social Democratic Party (ČSSD), the Christian-Democratic Union – Czecho- slovak Peoples Party (KDU-ČSL), and the Union of Freedom – Democratic Union (US-DEU), accompanied by some independent and small party Senators was able – just mathematically – to elect its own candidate. However, a split in the major coalition party ČSSD, and support given to Klaus by the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM), brought the Honorary Chairman of the ODS, Václav Klaus, to the Presidential offi ce. In February 2007, on the day of the forth anniversary of his fi rst elec- tion, Klaus announced that he would seek reelection in 2008. His party, the ODS, later formally approved his nomination and fi led his candidacy later in 2007. Klaus succeeded in his reelection attempt, but the way to defending the Presidency was long and complicated. In 2003 members of both houses of Parliament, who – according to the Constitution of the Czech Republic – elect the President at the Joint Session, had to meet three times before they elected the President, and each attempt took three rounds. -

The Macedonian “Name” Dispute: the Macedonian Question—Resolved?

Nationalities Papers (2020), 48: 2, 205–214 doi:10.1017/nps.2020.10 ANALYSIS OF CURRENT EVENTS The Macedonian “Name” Dispute: The Macedonian Question—Resolved? Matthew Nimetz* Former Personal Envoy of the Secretary-General of the United Nations and former Special Envoy of President Bill Clinton, New York, USA *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract The dispute between Greece and the newly formed state referred to as the “Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” that emerged out of the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1991 was a major source of instability in the Western Balkans for more than 25 years. It was resolved through negotiations between Athens and Skopje, mediated by the United Nations, resulting in the Prespa (or Prespes) Agreement, which was signed on June 17, 2018, and ratified by both parliaments amid controversy in their countries. The underlying issues involved deeply held and differing views relating to national identity, history, and the future of the region, which were resolved through a change in the name of the new state and various agreements as to identity issues. The author, the United Nations mediator in the dispute for 20 years and previously the United States presidential envoy with reference to the dispute, describes the basis of the dispute, the positions of the parties, and the factors that led to a successful resolution. Keywords: Macedonia; Greece; North Macedonia; “Name” dispute The Macedonian “name” dispute was, to most outsiders who somehow were faced with trying to understand it, certainly one of the more unusual international confrontations. When the dispute was resolved through the Prespa Agreement between Greece and (now) the Republic of North Macedonia in June 2018, most outsiders (as frequently expressed to me, the United Nations mediator for 20 years) responded, “Why did it take you so long?” And yet, as protracted conflicts go, the Macedonian “name” dispute is instructive as to the types of issues that go to the heart of a people’s identity and a nation’s sense of security. -

Italy and the Regulation of Same-Sex Unions Alessia Donà*

Modern Italy, 2021 Vol. 26, No. 3, 261–274, doi:10.1017/mit.2021.28 Somewhere over the rainbow: Italy and the regulation of same-sex unions Alessia Donà* Department of Sociology and Social Research, University of Trento, Italy (Received 11 August 2020; final version accepted 6 April 2021) While almost all European democracies from the 1980s started to accord legal recogni- tion to same-sex couples, Italy was, in 2016, the last West European country to adopt a regulation, after a tortuous path. Why was Italy such a latecomer? What kind of barriers were encountered by the legislative process? What were the factors behind the policy change? To answer these questions, this article first discusses current morality policy- making, paying specific attention to the literature dealing with same-sex partnerships. Second, it provides a reconstruction of the Italian policy trajectory, from the entrance of the issue into political debate until the enactment of the civil union law, by considering both partisan and societal actors for and against the legislative initiative. The article argues that the Italian progress towards the regulation of same-sex unions depended on the balance of power between change and blocking coalitions and their degree of congru- ence during the policymaking process. In 2016 the government formed a broad consen- sus and the parliament passed a law on civil unions. However, the new law represented only a small departure from the status quo due to the low congruence between actors within the change coalition. Keywords: same-sex unions; party politics; morality politics; LGBT mobilisation; Catholic Church; veto players. -

A Perfect Storm: Macedonia's Political Chaos and the Refugee Crisis

A perfect storm: Macedonia’s political chaos and the refugee crisis blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/01/28/a-perfect-storm-macedonias-political-chaos-and-the-refugee-crisis/ 1/28/2016 Macedonia has been experiencing a prolonged political crisis, with the country’s Prime Minister, Nikola Gruevski, resigning in January this year ahead of new elections intended to be held in April. Dejan Marolov writes on the roots of the crisis and how the present standoff between the ruling party and the opposition has developed. He argues that resolving the political stalemate will be vital if Macedonia is to meet a number of key challenges it faces, such as the country’s location on one of the main routes for asylum seekers and migrants to travel into northern Europe. The Republic of Macedonia is facing possibly the toughest political crisis in its existence (if we exclude the armed conflict from 2001). As a result of the crisis, which was initiated by a phone tapping scandal, an EU-mediated agreement, known as the ‘Przino agreement’, was reached between the main political parties in July 2015 to undertake a series of measures to resolve the situation. This was to culminate in new, fair and democratic elections, which were set for April 2016. The resignation of the country’s Prime Minister, Nikola Gruevski, was part of this agreement – and it was this element that generated a particularly large level of attention. The roots of the current crisis Gruevski has been Prime Minister from mid-2006, which means he has governed the country for almost 10 years. -

Far from Stability: the Post-Election Landscape in Bulgaria Dariusz Kałan

No. 50 (503), 15 May 2013 © PISM Editors: Marcin Zaborowski (Editor-in-Chief) . Katarzyna Staniewska (Managing Editor) Jarosław Ćwiek-Karpowicz . Artur Gradziuk . Piotr Kościński Roderick Parkes . Marcin Terlikowski . Beata Wojna Far from Stability: The Post-Election Landscape in Bulgaria Dariusz Kałan Early parliamentary elections not only will not help restore political stability in Bulgaria but also could further deepen the chaos because of the high dispersion of votes and the expected difficulties with creating a coalition. For a country immersed in crisis, maintaining the post-election stalemate is particularly not beneficial because of the deteriorating economic situation and growing public pressure. Regardless of which party will return to power, one should not expect a significant improvement in Bulgaria’s image in the EU or a positive settlement of the most important issues, including the country’s rapid accession to the Schengen area. Although the winner of the early parliamentary elections of 12 May was the centre-right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB, 30% of votes), for all four parties that exceeded the 4% electoral threshold, the results can be seen as satisfactory. GERB, the ruling party in 2009–2013, won for the second time in a row during unfavourable economic and social situations. The similar support for the Bulgarian Socialist Party (27%), which received more than 600,000 additional votes than in 2009, is because of the mobilisation of its permanent electorate and generational changes in the party. Also, for the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (11%), which represents the Turkish minority, and the nationalist Attack party (7%), the results are a confirmation of their stable positions on the political scene. -

WHY COMPETITION in the POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA a Strategy for Reinvigorating Our Democracy

SEPTEMBER 2017 WHY COMPETITION IN THE POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA A strategy for reinvigorating our democracy Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter ABOUT THE AUTHORS Katherine M. Gehl, a business leader and former CEO with experience in government, began, in the last decade, to participate actively in politics—first in traditional partisan politics. As she deepened her understanding of how politics actually worked—and didn’t work—for the public interest, she realized that even the best candidates and elected officials were severely limited by a dysfunctional system, and that the political system was the single greatest challenge facing our country. She turned her focus to political system reform and innovation and has made this her mission. Michael E. Porter, an expert on competition and strategy in industries and nations, encountered politics in trying to advise governments and advocate sensible and proven reforms. As co-chair of the multiyear, non-partisan U.S. Competitiveness Project at Harvard Business School over the past five years, it became clear to him that the political system was actually the major constraint in America’s inability to restore economic prosperity and address many of the other problems our nation faces. Working with Katherine to understand the root causes of the failure of political competition, and what to do about it, has become an obsession. DISCLOSURE This work was funded by Harvard Business School, including the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness and the Division of Research and Faculty Development. No external funding was received. Katherine and Michael are both involved in supporting the work they advocate in this report.