Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ukraine As Manufacturing Hub

Ukraine as manufacturing hub Boosting value and reaching global market Introduction Yuliya Kovaliv Head of Office, National Investment Council of Ukraine As a result of changes in global geopolitical and international trade contexts, Ukraine emerged on investors’ radars as one of the key manufacturing hubs in Europe. Its beneficial location, well qualified labor force, affordably priced utilities, extensive transport infrastructure, and profound background in manufacturing make the country very attractive for export-oriented businesses. Historically, Ukraine had one of the strongest expertise in machine building among Eastern European and CIS countries. Designed and manufactured in Ukraine, sea vessels and railcars, motor vehicles and aircrafts were used domestically and exported across the world. Ukraine is known as designer and producer of a number of record-breaking machines like AN-225 Mriya – a famous aircraft with the highest carrying capacity and one the largest wingspan in the world. Up till now, expertise remains one of the principle advantages of Ukraine. In 1991, Ukraine gained independence and followed the course of economic reforms. Liberalized markets and free-trade agreements with 46 countries (the last one signed with Israel in January, 2019) resulted in the growing significance of Ukraine as a regional hub and improved its access to the global supply chain. Figures speak for themselves: export volumes in 11 months of 2018 grew by almost 10% and reached $43 billion, with exports to the EU taking over 42%. Now Ukraine is committed to further strengthen its position in the European and global manufacturing industry. For investors, opportunities are vast – from automotive spare parts production and food processing to shipbuilding and aerospace industry. -

Impact of Political Course Shift in Ukraine on Stock Returns

IMPACT OF POLITICAL COURSE SHIFT IN UKRAINE ON STOCK RETURNS by Oleksii Marchenko A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MA in Economic Analysis Kyiv School of Economics 2014 Thesis Supervisor: Professor Tom Coupé Approved by ___________________________________________________ Head of the KSE Defense Committee, Professor Irwin Collier __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Date ___________________________________ Kyiv School of Economics Abstract IMPACT OF POLITICAL COURSE SHIFT IN UKRAINE ON STOCK RETURNS by Oleksii Marchenko Thesis Supervisor: Professor Tom Coupé Since achieving its independence from the Soviet Union, Ukraine has faced the problem which regional block to integrate in. In this paper an event study is used to investigate investors` expectations about winners and losers from two possible integration options: the Free Trade Agreement as a part of the Association Agreement with the European Union and the Custom Union of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan. The impact of these two sudden shifts in the political course on stock returns is analyzed to determine the companies which benefit from each integration decisions. No statistically significant impact on stock returns could be detected. However, our findings suggest a large positive reaction of companies` stock prices to the dismissal of Yanukovych regime regardless of company`s trade orientation and political affiliation. -

Canada Gouvernementaux Canada

Public Works and Government Services Travaux publics et Services 1 1 Canada gouvernementaux Canada RETURN BIDS TO: Title - Sujet RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: SIMULATION ENTITY MODELS Bid Receiving - PWGSC / Réception des soumissions Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amendment No. - N° modif. - TPSGC W8475-135211/B 006 11 Laurier St. / 11, rue Laurier Client Reference No. - N° de référence du client Date Place du Portage, Phase III Core 0A1 / Noyau 0A1 W8475-135211 2014-03-20 Gatineau GETS Reference No. - N° de référence de SEAG Quebec PW-$$EE-048-26597 K1A 0S5 Bid Fax: (819) 997-9776 File No. - N° de dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME 048ee.W8475-135211 Time Zone SOLICITATION AMENDMENT Solicitation Closes - L'invitation prend fin at - à 02:00 PM Fuseau horaire MODIFICATION DE L'INVITATION Eastern Daylight Saving on - le 2014-04-25 Time EDT F.O.B. - F.A.B. The referenced document is hereby revised; unless otherwise indicated, all other terms and conditions of the Solicitation Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: remain the same. Address Enquiries to: - Adresser toutes questions à: Buyer Id - Id de l'acheteur Friesen, Manon 048ee Ce document est par la présente révisé; sauf indication contraire, Telephone No. - N° de téléphone FAX No. - N° de FAX les modalités de l'invitation demeurent les mêmes. (819) 956-1161 ( ) ( ) - Destination - of Goods, Services, and Construction: Destination - des biens, services et construction: Comments - Commentaires Vendor/Firm Name and Address Instructions: See Herein Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l'entrepreneur Instructions: Voir aux présentes Delivery Required - Livraison exigée Delivery Offered - Livraison proposée Vendor/Firm Name and Address Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l'entrepreneur Issuing Office - Bureau de distribution Telephone No. -

Passenger Cars – 109 898 Units in February 2021, up 1.7% YOY; 205 903 Units in January-February 2021, Down 2.4% YOY

PRESS-RELEASE 17 MARCH 2021 AUTOMOBILE MARKET OF RUSSIA IN FEBRUARY AND JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2021 In February 2021, sales of new MOTOR VEHICLES in Russia, based on registration data, grew by 2.4% year- on-year to 125 936 vehicles. In January-February 2021, the total sales were 235 280 vehicles*, down 2.4% year-on-year, of which: • Passenger cars – 109 898 units in February 2021, up 1.7% YOY; 205 903 units in January-February 2021, down 2.4% YOY. Among them electric vehicles – 75 units in February 2021, up 435.7% YOY; 186 units in January-February 2021, up 675.0% YOY. • Light commercial vehicles including light trucks (N1 category, without pickups) and minibuses (M2 category) – 8 590 units in February 2021, up 16.5% YOY; 15 603 units in January-February 2021, up 7.2% YOY. • Picku ps – 610 units in February 2021, down 23.8% YOY; 1 090 units in January-February 2021, down 37.6% YOY. • Truck s (except N1 category) including special-purpose vehicles – 6 093 units in February 2021, up 10.5% YOY; 10 984 units in January-February 2021, down 3.4% YOY. • Buses (except М2 category) – 745 units in February 2021, down 39.9% YOY; 1 700 units in January-February 2021, down 27.0% YOY. *without sales to military, law enforcement and diplomatic agencies in RF COMMENT: Alexander Kovrigin, Deputy Managing Director of ASM Holding, commented: Sales of passenger cars in February 2021 were up 1.7% year-on-year and down 2.4% year-to-date. We expect a slight decrease of sales in March, to be followed by beginning of growth. -

Truck Market 2024 Sustainable Growth in Global Markets Editorial Welcome to the Deloitte 2014 Truck Study

Truck Market 2024 Sustainable Growth in Global Markets Editorial Welcome to the Deloitte 2014 Truck Study Dear Reader, Welcome to the Deloitte 2014 Truck Study. 1 Growth is back on the agenda. While the industry environment remains challenging, the key question is how premium commercial vehicle OEMs can grow profitably and sustainably in a 2 global setting. 3 This year we present a truly international outlook, prepared by the Deloitte Global Commercial 4 Vehicle Team. After speaking with a selection of European OEM senior executives from around the world, we prepared this innovative study. It combines industry and Deloitte expert 5 insight with a wide array of data. Our experts draw on first-hand knowledge of both country 6 Christopher Nürk Michael A. Maier and industry-specific challenges. We hope you will find this report useful in developing your future business strategy. To the 7 many executives who took the time to respond to our survey, thank you for your time and valuable input. We look forward to continuing this important strategic conversation with you. Using this report In each chapter you will find: • A summary of the key messages and insights of the chapter and an overview of the survey responses regarding each topic Christopher Nürk Michael A. Maier • Detailed materials supporting our findings Partner Automotive Director Strategy & Operations and explaining the impacts for the OEMs © 2014 Deloitte Consulting GmbH Table of Contents The global truck market outlook is optimistic Yet, slow growth in key markets will increase competition while growth is shifting 1. Executive Summary to new geographies 2. -

Almanac on Security Sector Governance in Ukraine 2010

Almanac on Security Sector Governance in Ukraine 2010 Partnership Network Security and Defence Management Series no. 2 Almanac on Security Sector Governance in Ukraine 2010 Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) www.dcaf.ch The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces is one of the world’s leading institutions in the areas of security sector reform (SSR) and security sector governance (SSG). DCAF provides in-country advisory support and practical assistance programmes, develops and promotes appropriate democratic norms at the international and national levels, advocates good practices and makes policy recommendations to ensure effective democratic governance of the security sector. DCAF’s partners include governments, parliaments, civil society, international organisations and the range of security sector actors such as police, judiciary, intelligence agencies, border security services and the military. 2010 Almanac on Security Sector Governance in Ukraine 2010 Geneva, 2010 Partnership Network, Almanac on Security Sector Governance in Ukraine 2010, edited by Merle Maigre and Philipp Fluri (Geneva: Geneva Centre for the De- mocratic Control of Armed Forces, 2010). Security and Defence Management Series no. 2 © Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces, 2010 Executive publisher: Procon Ltd., <www.procon.bg> Cover design: Hristo Bliznashki ISBN 978-92-9222-116-4 (DCAF) ISBN 978-954-92521-2-5 (Procon) FOREWORD Strengthening the role of a civil society in providing for effective oversight of security activities and developing civil society expertise in defence and security issues are amongst the principal objectives of NATO-Ukraine co-operation in implementing de- fence and security sector reform. -

Worldwide Equipment Guide

WORLDWIDE EQUIPMENT GUIDE TRADOC DCSINT Threat Support Directorate DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. Worldwide Equipment Guide Sep 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Page Memorandum, 24 Sep 2001 ...................................... *i V-150................................................................. 2-12 Introduction ............................................................ *vii VTT-323 ......................................................... 2-12.1 Table: Units of Measure........................................... ix WZ 551........................................................... 2-12.2 Errata Notes................................................................ x YW 531A/531C/Type 63 Vehicle Series........... 2-13 Supplement Page Changes.................................... *xiii YW 531H/Type 85 Vehicle Series ................... 2-14 1. INFANTRY WEAPONS ................................... 1-1 Infantry Fighting Vehicles AMX-10P IFV................................................... 2-15 Small Arms BMD-1 Airborne Fighting Vehicle.................... 2-17 AK-74 5.45-mm Assault Rifle ............................. 1-3 BMD-3 Airborne Fighting Vehicle.................... 2-19 RPK-74 5.45-mm Light Machinegun................... 1-4 BMP-1 IFV..................................................... 2-20.1 AK-47 7.62-mm Assault Rifle .......................... 1-4.1 BMP-1P IFV...................................................... 2-21 Sniper Rifles..................................................... -

2 General Description of the Russian-Made Vehicle Fleet

;-.. ; : s -- 0--21297 .4 { Public Disclosure Authorized VehicleFle'et Public Disclosure Authorized Characterizationin CentralAsia and, the Caucasus Public Disclosure Authorized Reportfor the RegionalStudy on: CleanerTransportation FuelIs for UrbanAir QualityImprovement Public Disclosure Authorized inCentralAsia -and the Caucasus Vehicle Fleet Characterization in Central Asia and the Caucasus Report for the Regional Study on: Cleaner Transportation Fuels for Urban Air Quality Improvement in Central Asia and the Caucasus Canadian International Development Agency Joint UNDPlWorld Bank Energy Sector ManagementAssistance Programme (ESMAP) Contents Acknowledgments ............................................... vii Abbreviations and Acronyms ............................................... ix Executive Summary ............................................... xi Vehicle Technology in Central Asia and the Caucasus........................................ xii Fleet Octane Requirements ........................................ xiii Inspection and Maintenance Programs ........................................ xiv Uzbekistan's Natural Gas Conversion Program ........................................ xvi Conclusions and Recommendations ....................................... xvii 1 Introduction ................................................ 1 1.1 Objectives .1 1.2 Background .2 Impact of Fuel on Vehicle Emissions .2 Long Range Effects of Emissions .2 Climate Change and Greenhouse Gases .2 Impact of Fuel on Vehicle Technology. 3 1.3 Study Methodology.3 -

CATALOGUE Tribo Is a Steadily Growing Group of Companies, Founded in 1979

friction products manufacturer CATALOGUE Tribo is a steadily growing group of companies, founded in 1979. There is a modern testing laboratory Tribo is the largest manufacturer of friction products in the East European region. located at Tribo, which makes it possible to perform quality control and develop the new products. Tribo produces more than 800 different products for such industrial groups as railway transport, commercial vehicles, agricultural, industrial and special equipment. Tribo production meets the following CIS and European The coordinated work and development of the company are provided by subsidiaries: quality standards: Tribo Tools (metal working and mold production) (friction products development and testing) Tribo R&D ISO 9001:2015 Tribo Rail UK (friction products for the European market) ISO 14001:2015 Tribo Trade (raw materials wholesale trade for the chemical industry) IATF 16949:2016 ECE R90 OUR CLIENTS: CONTENTS Railway products ....................................................................................... 8 Brake pads ................................................................................................... 14 Special vehicles products ........................................................................ 20 Brake linings ............................................................................................... 26 Brake discs and clutch facings ............................................................. 34 Ж/Д ПРОДУКЦИЯ Geosynthetics ........................................................................................... -

GAZ Group Annual Report 2008

Annual Report 2008 GAZ Group 1 Contents Statement of the Chairman of the Management Board ........................................................................ 3 GAZ Group general information .......................................................................................................... 5 GAZ Group profile ........................................................................................................................... 5 GAZ Group mission and strategy..................................................................................................... 7 Organizational structure ................................................................................................................... 9 Key events of 2008......................................................................................................................... 10 Key events of the beginning of 2009.............................................................................................. 17 Main lines of business ........................................................................................................................ 19 Light commercial vehicles (LCV) and medium commercial vehicles (MCV) .............................. 19 Buses............................................................................................................................................... 25 Trucks ............................................................................................................................................. 30 Construction -

Ukrainian Light Vehicle

ukrainian defense review ] The SeRvice Of «KRAZ» ber-December 2014 O Oct [ №4 UKRAINIAN DOZORLIGHT VEHICLE MicROWAve RAiDeRS mSARMATulti-target NewfROM advantages UKRAiN e remote weapon mASSAULTi-24G – South POW AfricaneR and Ukrainian for self-protection station modernization for Azerbaijan means [ table of contents ] hot topic electronic intelligence Electronic40 pAss reconnaissanceIVe LOCATION had always been of particular importance for the armed forces, pro- Ukrainian army began to take delivery of all-terrain wheeled viding information of interest to the country’s 10 KRAZ TRUCKs ON MILITARY seRVICe top political leadership. Produced in Ukraine vehicles produced by KRAZ PJSC Kolchuga station had provided detection capabil- ities for both ground and airborne radio emitters hydrodevices 44 «seA WOLf» SonobuoysHUNT areeR sused for cooperation detecting submerged ob- jects in primary and sec- direct speech ondary hydroacoustic South30 Ass Africaault and Ukraine pow ehaveR im- fields. Also, there are plemented a collaborative program radio sonobuoys for 18 We OffeR OUR CUsTOMeRs to upgrade the Azerbaijan Air Force special applications Mi-24 attack helicopters to the Mi- which are capable AN eXTeNsIVe RANGe 24G Super ‘Hind’ standard of detecting electric fields and magnetic InterviewOf withARMOR CEO ofed Streit Ve GroupHICLes disturbances gener- ated by submarines. radars hi-tech 48 Quantum LeAp bY UKRAINe’s defeNse 34 MICROWAVe In thee USSR,LeCTRONIC the equipments INd designedUstry and developed by SE RI “Kvant” was seen light armor dIVeRsIO NIsT deployed on all but every surface naval fROM UKRAINe ship, strategic submarine and different Some countries have recently invested types of commercial ships great effort and resources in developing Engineers24 UNde at RKharkiv THe GUARMorozovd MachineOf dOZOR Design and building high-power microwave tech- Bureau have developed the DOZOR family of nology. -

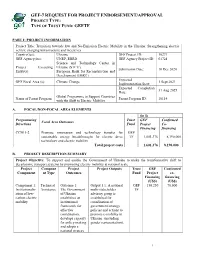

Project Document

GEF-7 REQUEST FOR PROJECT ENDORSEMENT/APPROVAL PROJECT TYPE: TYPE OF TRUST FUND: GEFTF PART I: PROJECT INFORMATION Project Title: Transition towards low and No-Emission Electric Mobility in the Ukraine: Strengthening electric vehicle charging infrastructure and incentives Country(ies): Ukraine GEF Project ID: 10271 GEF Agency(ies): UNEP, EBRD GEF Agency Project ID: 01724 Science and Technology Center in Project Executing Ukraine (STCU), Submission Date: 10 Dec 2020 Entity(s): European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Expected GEF Focal Area (s): Climate Change 1 Sept 2021 Implementation Start: Expected Completion 31 Aug 2025 Date: Global Programme to Support Countries Name of Parent Program Parent Program ID: 10114 with the Shift to Electric Mobility A. FOCAL/NON-FOCAL AREA ELEMENTS (in $) Programming Trust GEF Confirmed Focal Area Outcomes Directions Fund Project Co- Financing financing CCM 1-2 Promote innovation and technology transfer for GEF sustainable energy breakthroughs for electric drive TF 1,601,376 8,190,000 technology and electric mobility Total project costs 1,601,376 8,190,000 B. PROJECT DESCRIPTION SUMMARY Project Objective: To support and enable the Government of Ukraine to make the transformative shift to decarbonize transport systems by promoting electric mobility at national scale Project Compone Project Project Outputs Trust GEF Confirmed Component nt Type Outcomes Fund Project co- Financing financing (US$) (US$) Component 1: Technical Outcome 1: Output 1.1: A national GEF 150,250 70,000 Institutionaliz Assistance The Government multi-stakeholder TF ation of low- of Ukraine advisory group is carbon electric establishes an established for mobility institutional coordination of framework for government strategy, effective policies and actions to coordination, promote e-mobility in develops capacity Ukraine.