Walter Benjamin's Progressive Cultural Production and DIY Punk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who in Basque Music Today

Who’s Who in Basque music today AKATZ.- Ska and reggae folk group Ganbara. recorded in 2000 at the circles. In 1998 the band DJ AXULAR.- Gipuzkoa- Epelde), accomplished big band from Bizkaia with Accompanies performers Azkoitia slaughterhouse, began spreading power pop born Axular Arizmendi accordionist associated a decade of Jamaican like Benito Lertxundi, includes six of their own fever throughout Euskadi adapts the txalaparta to invariably with local inspiration. Amaia Zubiría and Kepa songs performed live with its gifted musicians, techno music. In his second processions, and Angel Junkera, in live between 1998 and 2000. solid imaginative guitar and most recent CD he also Larrañaga, old-school ALBOKA.-Folk group that performances and on playing and elegant adds voices from the bertsolari and singer who has taken its music beyond record. In 2003 he recorded melodies. Mutriku children's choir so brilliantly combines our borders, participating a CD called "Melodías de into the mix, with traditional sensibilities and in festivals across Europe. piel." CAMPING GAZ & DIGI contributions by Mikel humor, are up to their ears Instruments include RANDOM.- Comprised of Laboa. in a beautiful, solid and alboka, accordion and the ANJE DUHALDE.- Singer- Javi Pez and Txarly Brown enriching project. Their txisu. songwriter who composes from Catalonia, the two DOCTOR DESEO.- Pop rock fresh style sets them apart. in Euskara. Former member joined forces in 1995, and band from Bilbao. They are believable, simple, ALEX UBAGO.-Donostia- of late 70s folk-rock group, have since played on and Ringleader Francis Díez authentic and, most born pop singer and Errobi, and of Akelarre. -

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Juin 2013 À 20H30 Le Plus En Vue Du Moment: the Upbeats

la programmation de Forde bénéficie le Moloko ne bénéficie pas d’autre soutien que de celui de ses nombreux-ses ami-es le Zoo ne bénéficie pas d’autre soutien que de celui de ses amis Nous voila rendus au dernier stade du processus : le grand du soutien de la Ville de Genève Samedi 22 Juin oral final ! Selon le principe de l'autogestion (qui nous est chère) Salle ... de nuit IN THE MOOD FOR tou.te.s les membres sont appelé à élire leur futur.e col- 4 place des volontaires, VIOLENCE [DUBSTEP] JUIN 201 JUIN lègue et représentant.e. 1er étage, droite BAR9 Z Audio, Audio Freaks, Dark Circles / UK Chaque candidat se présente donc devant l’association + : www.lezoo.ch (une cinquantaine de membres environ y assiste) qui, sui- BARE NOIZE Eight:FX, Audio Freaks, Buygore / UK te à ces entretiens grandeur nature, vote. WICKED ONE Cover Your Face / CH Fin du processus !! ... Wow wow wow! Watch out Genève, deux pointures de la ... qui recommence à chaque tournus au sein de la dubstep débarquent en ville! Pour cette deuxième soirée de permanence ! 1er étage, gauche , la fête de la musique, le Zoo vous offre LE plateau dont vous Buvette 4 place des volontaires rêvez. Tout d'abord le genevois Wicked One, qu'on a pu L'Usine dépense donc sans compter son temps et son www.darksite.ch/moloko écouter au côté de Datsik il y a peu de temps, viendra nous énergie pour élire ses permanent.e.s ! socio-culturelle préchauffer les oreilles avant de laisser la place à deux pontes C'est qu'elle les aime ! (et qu'illes le lui rendent bien!) Ouvert de 20h à 3h (non-fumeur) de la dubstep dirty, les anglais Bar9 et Bare Noize. -

25-29 Music Listings 4118.Indd

saturday–sunday MUSIC Ladysmith Black Mambazo Guantanamo Baywatch, Hurry Up, SUNDAY, MARCH 8 [AFRIcA’S GoLDEn tHRoAtS] the Cumstain, Pookie and Poodlez legendary, Grammy-hoarding South [GARAGE RocK] on its new single African vocal group, now halfway Retox, Whores, ”too Late,” Portland’s Guantanamo through its fifth decade, has tran- Rabbits, Phantom Family Baywatch trades its formerly scended the Western pop notori- [HARDCORE] Fatalist, nihilist, blis- reverb-flooded garage-rock sound ety that followed its contributions tering, brutal—these are just a few for tamer, Motown-influenced bal- to Paul Simon’s Graceland, becom- of the better words to describe ladry. It’s a signal that the upcom- ing a full-fledged ambassador for hardcore crew Retox, a group whose ing Darling…It’s Too Late, dropping the culture of its homeland. But pedigree includes members of sim- in May on Suicide Squeeze, may one doesn’t need familiarity with ilarly thorny outfits such as the fully shift the band away from that its lengthy history to be stirred Locust, Head Wound city and Holy signature Burger Records’ sound, by those golden voices. Aladdin Molar. one adjective that doesn’t which has flooded the market Theater, 3017 SE Milwaukie Ave., get used very often, though it with pseudo-psychedelic surf-rock 234-9694. 8 pm. $35. 21+. should, is “funny.” It’s understand- groups indistinguishable from one able that this quality wouldn’t trans- another. LUcAS cHEMOTTI. The late through singer Justin Pearson’s Low Cut Connie Know, 2026 NE Alberta St., 473- larynx-ripping screech. But Retox [tHE WHItE KEYS] An invasive 8729. -

Here Were Homeless People All Around Us and a Lot of Fighting Going On

GUILT Ati Moran (Breaking Free Fanzine) on hardcore: Hardcore for me is definitely an idea, an expression of feelings and [an attitude of] never giving up on what you believe in. [It’s] an emotion you feel strong about that no one can take away from you! I also be- lieve hardcore has a lot to do with the people I met in the last 22 years who were apart of the scene - they weren’t everyday people. Besides hardcore being music, it was a place to get away from the normal world! Charles Maggio (Rorschach, Gern Blandsten Records) on hardcore: John Brannon said it best: hardcore is the “blues of the suburbs.” QUICKsaND Walter Schreifels (Quicksand, Gorilla Biscuits) on fighting/ disagreements in hardcore: In the scene there were homeless people all around us and a lot of fighting going on. There was the whole punks versus skins thing. There was that back drop, so it was a pretty obvious place to say something about it, and it’s cool to have a scene that allows for that discussion. That’s what gives it power in a way. The hardcore scene is like high school. There’s the typical bullshit that goes on everywhere, but it’s cooler because it’s like a musical high school and there’s something kind of romantic about that. There was also a lot of back and forth between hip- hop and hardcore at the time, too. There was a time when there was a lot of racism but there was a whole backlash against that. -

Family Album

1 2 Cover Chris Pic Rigablood Below Fabio Bottelli Pic Rigablood WHAT’S HOT 6 Library 8 Rise Above Dead 10 Jeff Buckley X Every Time I Die 12 Don’t Sweat The Technique BACKSTAGE 14 The Freaks Come Out At Night Editor In Chief/Founder - Andrea Rigano Converge Art Director - Alexandra Romano, [email protected] 16 Managing Director - Luca Burato, [email protected] 22 Moz Executive Producer - Mat The Cat E Dio Inventò... Editing - Silvia Rapisarda 26 Photo Editor - Rigablood 30 Lemmy - Motorhead Translations - Alessandra Meneghello 32 Nine Pound Hammer Photographers - Luca Benedet, Mattia Cabani, Lance 404, Marco Marzocchi, 34 Saturno Buttò Alex Ruffini, Federico Vezzoli, Augusto Lucati, Mirko Bettini, Not A Wonder Miss Chain And The Broken Heels - Tour Report Boy, Lauren Martinez, 38 42 The Secret Illustrations - Marcello Crescenzi/Rise Above 45 Jacopo Toniolo Contributors - Milo Bandini, Maurice Bellotti/Poison For Souls, Marco Capelli, 50 Conkster Marco De Stefano, Paola Dal Bosco, Giangiacomo De Stefano, Flavio Ignelzi, Brixia Assault Fra, Martina Lavarda, Andrea Mazzoli, Eros Pasi, Alex ‘Wizo’, Marco ‘X-Man’ 58 Xodo, Gonz, Davide Penzo, Jordan Buckley, Alberto Zannier, Michele & Ross 62 Family Album ‘Banda Conkster’, Ozzy, Alessandro Doni, Giulio, Martino Cantele 66 Zucka Vs Tutti Stampa - Tipografia Nuova Jolly 68 Violator Vs Fueled By Fire viale Industria 28 Dear Landlord 35030 Rubano (PD) 72 76 Lagwagon Salad Days Magazine è una rivista registrata presso il Tribunale di Vicenza, Go Getters N. 1221 del 04/03/2010. 80 81 Summer Jamboree Get in touch - www.saladdaysmag.com Adidas X Revelation Records [email protected] 84 facebook.com/saladdaysmag 88 Highlights twitter.com/SaladDays_it 92 Saints And Sinners L’editore è a disposizione di tutti gli interessati nel collaborare 94 Stokin’ The Neighbourhood con testi immagini. -

The Educative Experience of Punk Learners

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 6-1-2014 "Punk Has Always Been My School": The Educative Experience of Punk Learners Rebekah A. Cordova University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Recommended Citation Cordova, Rebekah A., ""Punk Has Always Been My School": The Educative Experience of Punk Learners" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 142. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/142 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. “Punk Has Always Been My School”: The Educative Experience of Punk Learners __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Morgridge College of Education University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Rebekah A. Cordova June 2014 Advisor: Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher i ©Copyright by Rebekah A. Cordova 2014 All Rights Reserved ii Author: Rebekah A. Cordova Title: “Punk has always been my school”: The educative experience of punk learners Advisor: Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher Degree Date: June 2014 ABSTRACT Punk music, ideology, and community have been a piece of United States culture since the early-1970s. Although varied scholarship on Punk exists in a variety of disciplines, the educative aspect of Punk engagement, specifically the Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethos, has yet to be fully explored by the Education discipline. -

Touchable Sound Records from the USA

A Collection of 7-inch Touchable Sound Records from the USA In an era that advocates streamlined product, and music at the click of a mouse, Touchable Sound celebrates those independent-minded bands and labels that make their own records and relish the opportunity to produce labor- intensive one-off artifacts. As Henry H. Owings puts it in his introduction, the book honors “those who invest countless hours of themselves to further their art. It’s about having an attention to detail and a disinterest in the bottom line.” Curated by Brian Roettinger, Mike Treff, and Diego Hadis, and organized by region, Touchable Sound focuses on unique, exquisite examples of American 7-inch-record design. Spanning nearly 25 years, it lovingly documents the obscure and the hard-to-find with help from musicians, artists, and label owners. Many of these records—by bands as diverse as the Olivia Tremor Control, the Locust, Angel Hair, Stereolab, Los Crudos, the Melvins, and more— have never before been seen by a wide audience, and were originally pressed in extremely limited editions. Edited by Brian Roettinger, Mike Treff, and Diego Hadis. Introduction by Henry Owings (Chunklet Magazine & Books). Essay Contributions from Tom Hazelmyer (Amphetamine Reptile Records), Sam McPheeters (Vermiform Records / Born Against), Justin Pearson (Three One G Records / The Locust), Kristin Thomson (Simple Machines Records / Tsunami), Mike Amezcua (El Grito Records), Mark Ownes (Life of the Mind). Featuring over 300 records and 600 bands. All images photographed. Full marketing and publicity campaign planned. Release events scheduled throughout the Fall. Display copies and POP materials available. -

Carlton Barrett

! 2/,!.$ 4$ + 6 02/3%2)%3 f $25-+)4 7 6!,5%$!4 x]Ó -* Ê " /",½-Ê--1 t 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE !UGUST , -Ê Ê," -/ 9 ,""6 - "*Ê/ Ê /-]Ê /Ê/ Ê-"1 -] Ê , Ê "1/Ê/ Ê - "Ê Ê ,1 i>ÌÕÀ} " Ê, 9½-#!2,4/."!22%44 / Ê-// -½,,/9$+.)"" 7 Ê /-½'),3(!2/.% - " ½-Ê0(),,)0h&)3(v&)3(%2 "Ê "1 /½-!$2)!.9/5.' *ÕÃ -ODERN$RUMMERCOM -9Ê 1 , - /Ê 6- 9Ê `ÊÕV ÊÀit Volume 36, Number 8 • Cover photo by Adrian Boot © Fifty-Six Hope Road Music, Ltd CONTENTS 30 CARLTON BARRETT 54 WILLIE STEWART The songs of Bob Marley and the Wailers spoke a passionate mes- He spent decades turning global audiences on to the sage of political and social justice in a world of grinding inequality. magic of Third World’s reggae rhythms. These days his But it took a powerful engine to deliver the message, to help peo- focus is decidedly more grassroots. But his passion is as ple to believe and find hope. That engine was the beat of the infectious as ever. drummer known to his many admirers as “Field Marshal.” 56 STEVE NISBETT 36 JAMAICAN DRUMMING He barely knew what to do with a reggae groove when he THE EVOLUTION OF A STYLE started his climb to the top of the pops with Steel Pulse. He must have been a fast learner, though, because it wouldn’t Jamaican drumming expert and 2012 MD Pro Panelist Gil be long before the man known as Grizzly would become one Sharone schools us on the history and techniques of the of British reggae’s most identifiable figures. -

The Music (And More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report

The Music (and More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report Report covers the time period of July 1st to Kieran Robbins & Chief - "Sway" [glam rock] September 30th, 2019. I inadvertently missed Troy a few before that time period, which were brought to my attention by fans, bands & Moriah Formica - "I Don't Care What You others. The missing are listed at the end, along with an Think" (single) [hard rock] Albany End Note… Nine Votes Short - "NVS: 09/03/2019" [punk rock] RECORDINGS: Albany Hard Rock / Metal / Punk Psychomanteum - "Mortal Extremis" (single track) Attica - "Resurected" (EP) [hardcore metal] Albany [thrash prog metal industrial] Albany Between Now and Forever - "Happy" (single - Silversyde - "In The Dark" [christian gospel hard rock] Mudvayne cover) [melodic metal rock] Albany Troy/Toledo OH Black Electric - "Black Electric" [heavy stoner blues rock] Scotchka - "Back on the Liquor" | "Save" (single tracks) Voorheesville [emo pop punk] Albany Blood Blood Blood - "Stranglers” (single) [darkwave Somewhere To Call Home - "Somewhere To Call Home" horror synthpunk] Troy [nu-metalcore] Albany Broken Field Runner – "Lay My Head Down" [emo pop Untaymed - "Lady" (single track) [british hard rock] punk] Albany / LA Colonie Brookline - "Live From the Bunker - Acoustic" (EP) We’re History - "We’re History" | "Pop Tarts" - [acoustic pop-punk alt rock] Greenwich "Avalanche" (singles) [punk rock pop] Saratoga Springs Candy Ambulance - "Traumantic" [alternative grunge Wet Specimens - "Haunted Flesh" (EP) [hardcore punk] rock] Saratoga Springs Albany Craig Relyea - "Between the Rain" (single track) Rock / Pop [modern post-rock] Schenectady Achille - "Superman (A Song for Mora)" (single) [alternative pop rock] Albany Dead-Lift - "Take It or Leave It" (single) [metal hard rock fusion] Schenectady Caramel Snow - "Wheels Are Meant To Roll Away" (single track) [shoegaze dreampop] Delmar Deep Slut - "u up?" (3-song) [punk slutcore rap] Albany Cassandra Kubinski - "DREAMS (feat. -

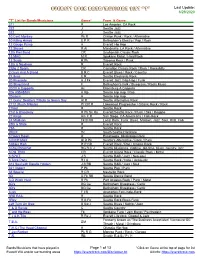

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "T" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre 311 R Los Angeles, CA Rock 322 J Seattle Jazz 322 J Seattle Jazz 10 Cent Monkey Pk R Clinton Punk / Rock / Alternative 10 Killing Hands E P R Bellingham's Electro / Pop / Rock 12 Gauge Pump H Everett Hip Hop 12 Stones R Al Mandeville, LA Rock / Alternative 12th Fret Band CR Snohomish Classic Rock 13 MAG M R Spokane Metal / Hard Rock 13 Scars R Pk Tacoma Rock / Punk 13th & Nowhere R Everett Rock 2 Big 2 Spank CR Carnation Classic Rock / Rock / Rockabilly 2 Guys And A Broad B R C Everett Blues / Rock / Country 2 Libras E R Seattle Electronic Rock 20 Riverside H J Fk Everett Jazz / Hip Hop / Funk 20 Sting Band F Bellingham's Folk / Bluegrass / Roots Music 20/20 A Cappella Ac Ellensburg A Cappella 206 A$$A$$IN H Rp Seattle Hip Hop / Rap 20sicem H Seattle Hip Hop 21 Guns: Seattle's Tribute to Green Day Al R Seattle Alternative Rock 2112 (Rush Tribute) Pr CR R Lakewood Progressive / Classic Rock / Rock 21feet R Seattle Rock 21st & Broadway R Pk Sk Ra Everett/Seattle Rock / Punk / Ska / Reggae 22 Kings Am F R San Diego, CA Americana / Folk-Rock 24 Madison Fk B RB Local Rock, Funk, Blues, Motown, Jazz, Soul, RnB, Folk 25th & State R Everett Rock 29A R Seattle Rock 2KLIX Hc South Seattle Hardcore 3 Doors Down R Escatawpa, Mississippi Rock 3 INCH MAX Al R Pk Seattle's Alternative / Rock / Punk 3 Miles High R P CR Everett Rock / Pop / Classic Rock 3 Play Ricochet BG B C J Seattle bluegrass, ragtime, old-time, blues, country, jazz 3 PM TRIO -

Atom and His Package Possibly the Smallest Band on the List, Atom & His

Atom and His Package Possibly the smallest band on the list, Atom & his Package consists of Adam Goren (Atom) and his package (a Yamaha music sequencer) make funny punk songs utilising many of of the package's hundreds of instruments about the metric system, the lead singer of Judas Priest and what Jewish people do on Christmas. Now moved on to other projects, Atom will remain the person who told the world Anarchy Means That I Litter, The Palestinians Are Not the Same Thing as the Rebel Alliance Jackass, and If You Own The Washington Redskins, You're a ****. Ghost Mice With only two members in this folk/punk band their voices and their music can be heard along with such pride. This band is one of the greatest to come out of the scene because of their abrasive acoustic style. The band consists of a male guitarist (I don't know his name) and Hannah who plays the violin. They are successful and very well should be because it's hard to 99 when you have such little to work with. This band is off Plan It X records and they put on a fantastic show. Not only is the band one of the leaders of the new genre called folk/punk but I'm sure there is going to be very big things to come from them and it will always be from the heart. Defiance, Ohio Defiance, Ohio are perhaps one of the most compassionate and energetic leaders of the "folk/punk" movement. Their clever lyrics accompanied by fast, melodic, acoustic guitars make them very enjoyable to listen to.