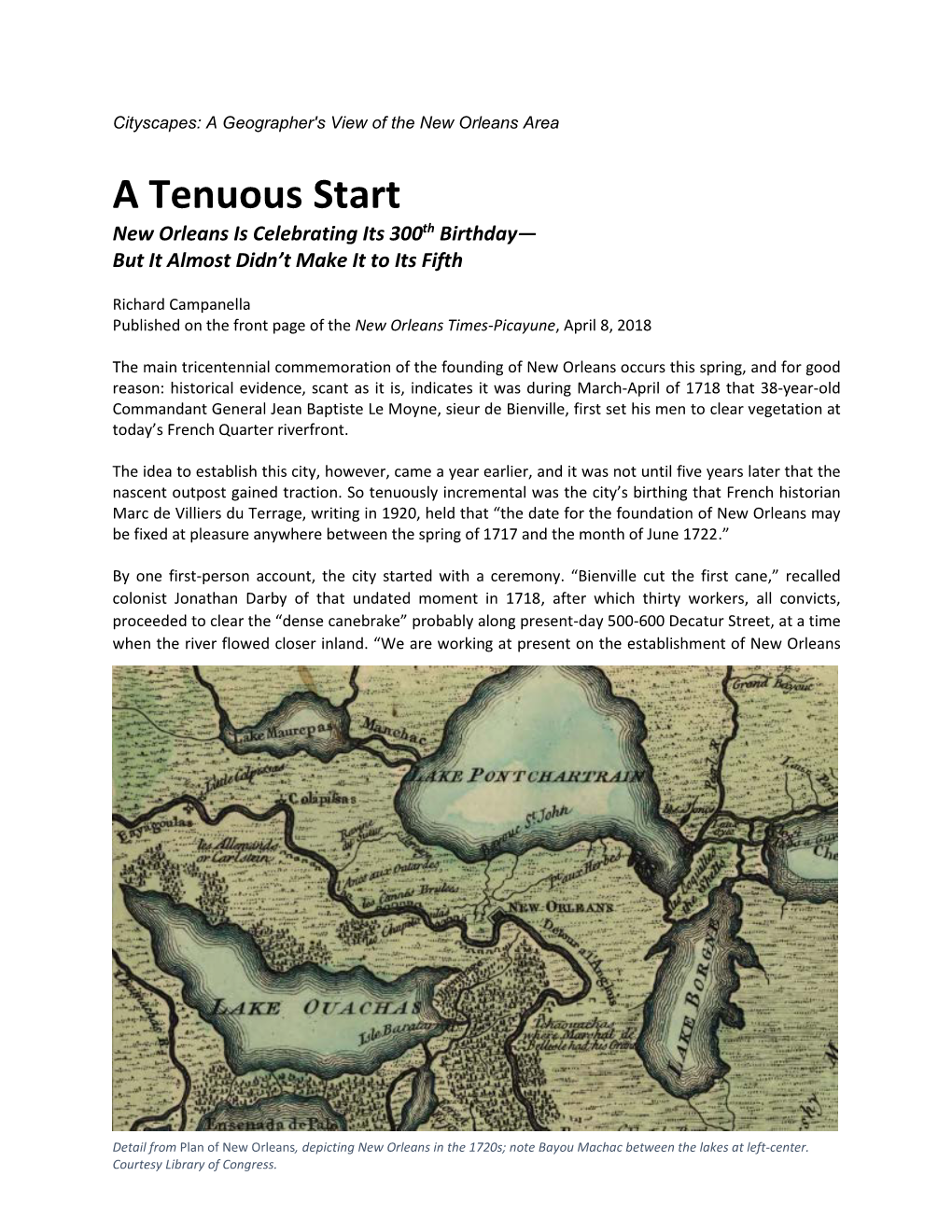

A Tenuous Start: New Orleans 1718-1722

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banquettes and Baguettes

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Banquettes and Baguettes “In the city’s early days, city blocks were called islands, and they were islands with little banks around them. Logically, the French called the footpaths on the banks, banquettes; and sidewalks are still so called in New Orleans,” wrote John Chase in his immensely entertaining history, “Frenchmen, Desire Good Children…and Other Streets of New Orleans!” This was mostly true in 1949, when Chase’s book was first published, but the word is used less and less today. In A Creole Lexicon: Architecture, Landscape, People by Jay Dearborn Edwards and Nicolas Kariouk Pecquet du Bellay de Verton, one learns that, in New Orleans (instead of the French word trottoir for sidewalk), banquette is used. New Orleans’ historic “banquette cottage (or Creole cottage) is a small single-story house constructed flush with the sidewalk.” According to the authors, “In New Orleans the word banquette (Dim of banc, bench) ‘was applied to the benches that the Creoles of New Orleans placed along the sidewalks, and used in the evenings.’” This is a bit different from Chase’s explanation. Although most New Orleans natives today say sidewalks instead of banquettes, a 2010 article in the Time-Picayune posited that an insider’s knowledge of New Orleans’ time-honored jargon was an important “cultural connection to the city”. The article related how newly sworn-in New Orleans police superintendent, Ronal Serpas, “took pains to re-establish his Big Easy cred.” In his address, Serpas “showed that he's still got a handle on local vernacular, recalling how his grandparents often instructed him to ‘go play on the neutral ground or walk along the banquette.’” A French loan word, it comes to us from the Provençal banqueta, the diminutive of banca, meaning bench or counter, of Germanic origin. -

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY German Immigration to Mainland

The Flow and the Composition of German Immigration to Philadelphia, 1727-177 5 IGHTEENTH-CENTURY German immigration to mainland British America was the only large influx of free white political E aliens unfamiliar with the English language.1 The German settlers arrived relatively late in the colonial period, long after the diversity of seventeenth-century mainland settlements had coalesced into British dominance. Despite its singularity, German migration has remained a relatively unexplored topic, and the sources for such inquiry have not been adequately surveyed and analyzed. Like other pre-Revolutionary migrations, German immigration af- fected some colonies more than others. Settlement projects in New England and Nova Scotia created clusters of Germans in these places, as did the residue of early though unfortunate German settlement in New York. Many Germans went directly or indirectly to the Carolinas. While backcountry counties of Maryland and Virginia acquired sub- stantial German populations in the colonial era, most of these people had entered through Pennsylvania and then moved south.2 Clearly 1 'German' is used here synonymously with German-speaking and 'Germany' refers primar- ily to that part of southwestern Germany from which most pre-Revolutionary German-speaking immigrants came—Cologne to the Swiss Cantons south of Basel 2 The literature on German immigration to the American colonies is neither well defined nor easily accessible, rather, pertinent materials have to be culled from a large number of often obscure publications -

Hand-Built Ceramics at 810 Royal and Intercultural Trade in French Colonial New Orleans

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Summer 8-5-2019 Hand-built Ceramics at 810 Royal and Intercultural Trade in French Colonial New Orleans Travis M. Trahan [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Trahan, Travis M., "Hand-built Ceramics at 810 Royal and Intercultural Trade in French Colonial New Orleans" (2019). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2681. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2681 This Thesis-Restricted is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis-Restricted in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis-Restricted has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hand-Built Ceramics at 810 Royal and Intercultural Trade in French Colonial New Orleans A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Urban Studies by Travis Trahan B.A. Loyola University of New Orleans, 2015 August, 2019 Table of Contents List of Figures and List of Tables ..................................................................................... -

A Perceptual History of New Orleans Neighborhoods

June 2014 http://www.myneworleans.com/New-Orleans-Magazine/ A Glorious Mess A perceptual history of New Orleans neighborhoods Richard Campanella Tulane School of Architecture We allow for a certain level of ambiguity when we speak of geographical regions. References to “the South,” “the West” and “the Midwest,” for example, come with the understanding that these regions (unlike states) have no precise or official borders. We call sub-regions therein the “Deep South,” “Rockies” and “Great Plains,” assured that listeners share our mental maps, even if they might outline and label them differently. It is an enriching ambiguity, one that’s historically, geographically and culturally accurate on account of its imprecision, rather than despite it. (Accuracy and precision are not synonymous.) Regions are largely perceptual, and therefore imprecise, and while many do embody clear geophysical or cultural distinctions – the Sonoran Desert or the Acadian Triangle, for example – their morphologies are nonetheless subject to the vicissitudes of human discernment. Ask 10 Americans to delineate “the South,” for instance, and you’ll get 10 different maps, some including Missouri, others slicing Texas in half, still others emphatically lopping off the Florida peninsula. None are precise, yet all are accurate. It is a fascinating, glorious mess. So, too, New Orleans neighborhoods – until recently. For two centuries, neighborhood identity emerged from bottom-up awareness rather than top-down proclamation, and mental maps of the city formed soft, loose patterns that transformed over time. Modern city planning has endeavored to “harden” these distinctions in the interest of municipal order – at the expense, I contend, of local cultural expressiveness. -

The French Natchez Settlement According to the Memory of Dumont De Montigny

The French Natchez Settlement According to the Memory of Dumont de Montigny TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements Chapter One: Introduction……………………………………………………..…...1 Chapter Two: Dumont de Montigny………………………………………….......15 Chapter Three: French Colonial Architecture………………………………….....28 Chapter Four: The Natchez Settlement: Analysis of Dumont’s Maps…..………..43 Chapter Five: Conclusion…………………………………………………………95 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………..105 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor Dr. Vincas Steponaitis for his endless support and guidance throughout the whole research and writing process. I would also like to thank my defense committee, Dr. Anna Agbe-Davies and Dr. Kathleen Duval, for volunteering their time. Finally I would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Jones who greatly assisted me by translating portions of Dumont’s maps. INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION The Natchez settlement, founded in 1716, was one of the many settlements founded by the French in the Louisiana Colony. Fort Rosalie was built to protect the settlers and concessions from the dangers of the frontier. Despite the military presence, the Natchez Indians attacked the settlement and destroyed the most profitable agricultural venture in Louisiana. While this settlement has not been excavated, many first-hand accounts exist documenting events at the settlement. The account this paper is concerned with is the work of Dumont de Montigny, a lieutenant and engineer in the French Army. Dumont spent his time in Louisiana creating plans and drawings of various French establishments, one of which being Fort Rosalie and the Natchez settlement. Upon his return to France, Dumont documented his experiences in Natchez in two forms, an epic poem and a prose memoir. Included in these works were detailed maps of Louisiana and specifically of the Natchez settlement. -

Straight Streets in a Curvaceous Crescent

Article Journal of Planning History 1-16 ª 2018 The Author(s) Straight Streets in a Curvaceous Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions Crescent: Colonial Urban DOI: 10.1177/1538513218800478 journals.sagepub.com/home/jph Planning and Its Impact on Modern New Orleans Richard Campanella1 Abstract New Orleans is justly famous for its vast inventory of historical architecture, representing scores of stylistic influences dating to the French and Spanish colonial eras. Less appreciated is the fact that the Crescent City also retains nearly original colonial urban designs. Two downtown neighborhoods, the French Quarter and Central Business District, are entirely undergirded by colonial-era planning, and dozens of other neighborhoods followed suit even after Americanization. New Orleanians who reside in these areas negotiate these colonial planning decisions in nearly every movement they make, and they reside in a state with as many colonial-era land surveying systems as can be found throughout the United States. This article explains how those patterns fell in place. Keywords New Orleans, Louisiana, cadastral systems, colonial planning, planning eras/approaches, French Quarter, surveying systems, French long lots Origins Men under the command of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville began clearing vegetation for La Nouvelle-Orle´ans in the early spring of 1718. Their proximate motivation was to establish a counter-office for the Company of the West, to which a monopoly charter had been granted by Philippe, the Duc d’Orle´ans and Regent of France, for the creation of an enslaved tobacco plantation economy. The ultimate motivation for the foundation of New Orleans was to create a French bulwark near the mouth of the Mississippi River to control access to France’s 1682 claim of the vast interior valley, while preventing the Spanish and English from doing the same.1 Where exactly to locate New Orleans had vexed French colonials. -

Chronicle of a Deflation Unforetold

Chronicle of a Deflation Unforetold Chronicle of a Deflation Unforetold Fran¸coisR. Velde Econometric Society N.A. Summer Meetings, June 24, 2007 Chronicle of a Deflation Unforetold Introduction Motivation Lucas's 1995 Nobel lecture begins with Hume (1752) to display a tension at the heart of macroeconomics: I neutrality of money seems \evident" I \If we consider any one kingdom by itself, it is evident that the greater or lesser plenty of money is of no consequence; since prices of commodities are always proportion'd to the plenty of money" I but experience shows otherwise I \tho' the high price of commodities be a necessary consequence of the encrease of gold and silver, yet it follows not immediately upon that encrease, but some time is requir'd before the money circulate thro' the whole state, and make its effects be felt on all ranks of people" ::: Mons. de Tot [Dutot]'s observations were generated by just such an experiment, and they don't support neutrality. Chronicle of a Deflation Unforetold Introduction Motivation (2) How did Hume reach these two conclusions? Mixture of I loosely referenced empirical observations I \These facts I give upon the authority of Mons. de Tot" I a priori reasoning: \magical" thought experiments I \suppose that, by miracle, every man in Britain shou'd have five pounds slipt into his pocket in one night" Chronicle of a Deflation Unforetold Introduction Motivation (2) How did Hume reach these two conclusions? Mixture of I loosely referenced empirical observations I \These facts I give upon the authority of Mons. de Tot" I a priori reasoning: \magical" thought experiments I \suppose that, by miracle, every man in Britain shou'd have five pounds slipt into his pocket in one night" ::: Mons. -

Chronicles of a Deflation Unforetold

Chronicles of a Deflation Unforetold Chronicles of a Deflation Unforetold Fran¸cois R. Velde Monetary and Financial History Workshop, Atlanta Fed 2006 Chronicles of a Deflation Unforetold Introduction Motivation Lucas’s 1995 Nobel lecture begins with Hume (1752): I neutrality of money “evident” I “If we consider any one kingdom by itself, it is evident that the greater or lesser plenty of money is of no consequence; since prices of commodities are always proportion’d to the plenty of money” I experience shows otherwise I “tho’ the high price of commodities be a necessary consequence of the encrease of gold and silver, yet it follows not immediately upon that encrease, but some time is requir’d before the money circulate thro’ the whole state, and make its effects be felt on all ranks of people” ... or was it? Hume was in fact referring to an actual experiment. Chronicles of a Deflation Unforetold Introduction Motivation (2) I How the quantity of money changes matters I Hume’s thought experiment “magical” I “suppose that, by miracle, every man in Britain shou’d have five pounds slipt into his pocket in one night” Chronicles of a Deflation Unforetold Introduction Motivation (2) I How the quantity of money changes matters I Hume’s thought experiment “magical” I “suppose that, by miracle, every man in Britain shou’d have five pounds slipt into his pocket in one night” ... or was it? Hume was in fact referring to an actual experiment. Chronicles of a Deflation Unforetold Introduction This paper A magical experiment: I from August 1723 to September 1724 -

Bristol, Africa and the Eighteenth Century Slave Trade To

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: JOSEPH BE1TEY, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. Assistant Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M.A., F.S.A. VOL. XLII BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 3 THE YEARS OF DECLINE 1746-1769 BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 3 THE YEARS OF DECLINE 1746-1769 EDITED BY DAYID RICHARDSON Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1991 ISBN 0 901538 12 4 ISSN 0305 8730 © David Richardson Bristol Record Society wishes to express its gratitude to the Marc Fitch Fund and to the University of Bristol Publications Fund for generous grants in support of this volume. Produced for the Society by Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, Stroud, Glos. Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements vi Introduction . vii Note on transcription xxxii List of abbreviations xxxiii ·Text 1 Index 235 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the process of ·compiling and editing the information on Bristol voyages to Africa contained in this volume I have received assistance and advice from various individuals and organisations. The task of collecting the material was made much easier from the outset by the generous help and advice I received from the staff at the Public Record Office, the Bristol Record Office, the Bristol Central Library and the Bristol Society of Merchant Venturers. I am grateful to the Society of Merchant Venturers for permission to consult its records and to cite material from them. I am also indebted to the British Academy for its generosity in awarding me a grant in order to allow me to complete my research on Bristol voyages to Africa. -

Story Behind the Stone Ch1.Pdf

St. Louis, King of France Between St. Louis Cathedral and the Presbytere o other American city has a cultural history St. Louis Cathedral is the focal point of Nas rich and vibrant as New Orleans does. Jackson Square. The original wooden structure Its roots are numerous and diverse, but the was built in 1718. A second church of brick taproot extends into French soil. construction was completed in 1727. One year The original French settlers made their way after this church was consumed in the Great from the Gulf of Mexico into Lake Borgne and New Orleans Fire of 1788, construction of the through the Rigolets into Lake Pontchartrain. current cathedral began and was completed From there, they traveled down Bayou St. in 1794. Benjamin Henry Latrobe designed the John and trekked over land to a place near the central tower in 1819. Mississippi River, where they established the Although Louis XIV was the king of France settlement. In charge was explorer Jean Baptiste when Iberville and his brother began to explore Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville. In 1721, Bienville’s the Gulf Coast, it was for Louis IX, St. Louis, engineer, Adrien de Pauger, laid out the initial that the cathedral was named. plans for a fortified city, a rectangular area St. Louis was the only canonized monarch bounded by Decatur Street, Rampart Street, of France. He was born on April 25, 1214, and Canal Street, and Esplanade Avenue. These died at the age of fifty-six on August 25, 1270. plans included space for the Place d’Armes, He was known for his religious devotion. -

The Value of Money in Eighteenth-Century England: Incomes, Prices, Buying Power— and Some Problems in Cultural Economics

The Value of Money in Eighteenth-Century England: Incomes, Prices, Buying Power— and Some Problems in Cultural Economics Robert D. Hume &'453&(5 Robert D. Hume offers an empirical investigation of incomes, cost, artist remuneration, and buying power in the realm of long eighteenth-century cultural production and purchase. What was earned by writers, actors, singers, musicians, and painters? Who could afford to buy a book? Attend a play or opera? Acquire a painting? Only 6 percent of families had £100 per annum income, and only about 3 percent had £200. What is the “buying power” magnitude of such sums? No single multiplier yields a legitimate present-day equivalent, but a range of 200 –300 gives a rough sense of magnitude for most of this period. Novels are now thought of as a bourgeois phenomenon, but they cost 3s. per volume. A family with a £200 annual income would have to spend nearly a full day’s income to buy a four-volume novel, but only 12 percent for a play. The market for plays was natu - rally much larger, which explains high copyright payments to playwrights and very low payments for most novels—hence the large number of novels by women, who had few ways to earn money. From this investigation we learn two broad facts. First, that the earnings of most writers, actors, musicians, and singers were gener - ally scanty but went disproportionately to a few stars, and second, that most of the culture we now study is inarguably elite: it was mostly consumed by the top 1 per - cent or 0.5 percent of the English population. -

Smallpox Inoculation in Britain, 1721-1830

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 1990 Pox Britannica: Smallpox Inoculation in Britain, 1721-1830 Deborah Christian Brunton University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Virus Diseases Commons Recommended Citation Brunton, Deborah Christian, "Pox Britannica: Smallpox Inoculation in Britain, 1721-1830" (1990). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 999. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/999 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/999 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pox Britannica: Smallpox Inoculation in Britain, 1721-1830 Abstract Inoculation has an important place in the history of medicine: not only was it the first form of preventive medicine but its history spans the so-called eighteenth century 'medical revolution'. A study of the myriad of pamphlets, books and articles on the controversial practice casts new light on these fundamental changes in the medical profession and medical practice. Whereas historians have associated the abandonment of old humoural theories and individualised therapy in favour of standardised techniques with the emergence of new institutions in the second half of the century, inoculation suggests that changes began as early as the 1720s. Though inoculation was initially accompanied by a highly individualised preparation of diet and drugs, more routinised sequences of therapy appeared the 1740s and by the late 1760s all inoculated patients followed exactly the same preparative regimen. This in turn made possible the institutionalised provision of inoculation, first through the system of poor relief, later by dispensaries and charitable societies.