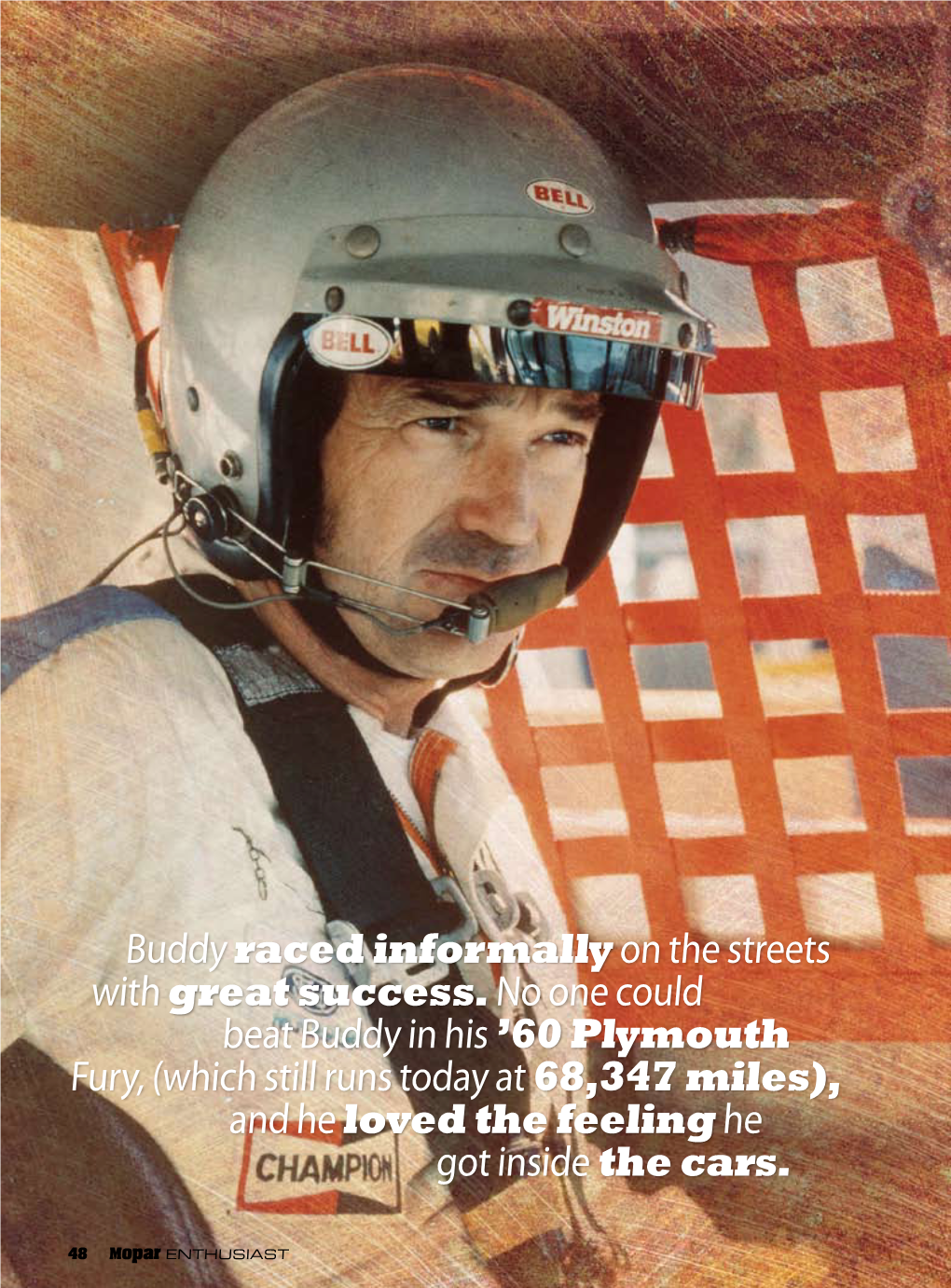

Buddy Raced Informallyon the Streets with Great

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holiday Catalog 2015 – 2016 R Cool Pe D U V S D S

Holiday Catalog 2015 – 2016 r Cool pe D u V S D s ! S EE PAGE 7 Reading for Racers Hot New Titles Most Popular This Year A HISTORY OF AUTO RACING Brand New from Coastal 181! IN NEW ENGLAND Vol. 1 FOYT, ANDRETTI, PETTY A Project of the North East America’s Racing Trinity Motor Sports Museum by Bones Bourcier An extraordinary compendium of the rich Were A.J. Foyt, Mario Andretti, and Richard Petty the history of stock-car, open-wheel, drag and three best racers in our nation’s history? Maybe yes, road racing in New England. Full of maybe no. But in weaving together their complex personal stories of drivers and tracks illustrated with tales, and examining the social and media climates of hundreds of photos, all contributed for the benefit of the their era, award-winning author Bones Bourcier shows North East Motor Sports Museum. Hard cover, 304 pp., why their names are still synonymous with the sport they carried to 400+ B&W photos. S-1405: $34.95 new heights. If you buy one racing book as a present, this should be it! Hard Cover, 288 pp., B&W photos. S-1500: $34.95 THE PEOPLE’S CHAMP A Racing Life Back by Popular Demand! by Dave Darland with Bones Bourcier The memoir of one of Sprint Car racing’s LANGHORNE! No Man’s Land most popular and talented racers, a by L. Spencer Riggs champion in all three of USAC’s national Reprinted at last, with all the original content, this divisions—Silver Crown, Sprint Cars, and award-winning volume covers the entire history of the Midgets—and still winning! Soft cover, 192 pp., world’s toughest mile, fr om its inception in 1926 to its 32 pp. -

Aug 2010.Pdf

July - August 2010 www.superbirdclub.com email: [email protected] Pete Hamilton Superbird Restoration Petty’s Garage in Level Cross North Carolina has unveiled their restoration of Pete Hamilton’s 1970 Daytona 500 winning Superbird race car. The car is owned by collector Todd Werner, who also owns a Petty 1971 Road Runner among quite a few other significant cars. At left in the group photo, you can see The King behind the car. Left of him is Dale Inman, and at the windshield pillar is Pete Hamilton crew chief, Richie Barsz. I am told that Richie was instrumental in visually identifying the car. Owner Todd Werner is second from left. There is not a lot of information about the history of the car that has been released publicly at this time. I am told that after 1970, the car was reportedly sold to privateer Doc Faustina , who entered it as a 1970 Road Runner in select Grand National races, s during 1971 and 1972. In later years, it was rebodied as a newer Charger and continued to race into the mid 1970’s. I hope to bring you more information about the car soon. At middle left, Richard is checking out the Maurice Petty built Hemi. You can see the car is still being lettered. Immediately after these photos were taken, the car was loaded up and headed for the Mopar Nationals in Columbus where it was on display in the Manufacturers Midway. Petty’s Garage is a specialty restoration facility operating from the former Petty Enterprises shops. 2010 Events Calendar page 2 September 9th-12th St Louis MO - Monster Mopar Weekend & Aero Car Display This event is coming up next month. -

Springfield Illinois the 2016 Be Held in Springfield in Conjunction with the International Route 66 Mother Road Festival

Feb-Mar-April 2016 www.superbirdclub.com email: [email protected] 2016 National Meet - September 20-25th, Springfield Illinois The 2016 be held in Springfield in conjunction with the International Route 66 Mother Road Festival. Our hosts are Sherri and Bill Peddicord. This will be a joint meet between the Winged Warriors group and DSAC. Members of the Dodge Charger Registry are also invited as it is the 50th anniversary of the Charger. The Festival Car show is Sept 23-25. The big show day is Saturday and the big cruise on Friday night. Sunday is a wind down day. So if you need to head home, no problem. Attendance each year exceeds 1000 cars . It is in Downtown Springfield Centering around the Old State Capital building. http://www.familyevents.com/international-route-66-mother-road-festival This is the link for the car show registration. Pre-registration is $40 and we get a $5 discount. They do include a t-shirt with the pre-registration. The pre-registration deadline is Sept 16. After that on Site registration is $55. Include “Superbird Club” on your registration form for the discount. The hotel that we have a room block is The Carpenter Street Hotel. It is similar to a Comfort Inn or Hampton Inn style. It is two blocks from the Abraham Lincoln Museum and about five blocks from the car show area. Several downtown restaurants are close by. If you plan to attend please make your reservations now. The Carpenter Street Hotel 217-789-9100 or 800-779-9200 525 North 6th Street www.carpenterstreethotel.com Springfield IL 62702 Room rate is $ 94.00 for Double Queen or King Rooms. -

Rear View Mirror

RReeaarr VViieeww MMiirrrroorr & Case History H. Donald Capps Volume 9 Number 2 / June 2011 Automobile Racing History From the Ashepoo & Combahee Drop Forge, Tool, Anvil & Research Works ◊ non semper ea sunt quae videntur – Phaedrus Pity the poor Historian! – Denis Jenkinson // Research is endlessly seductive; writing is hard work. – Barbara Tuchman Case History Indianapolis Motor Speedway: 1909 1 When the plans for the new speedway to be built on the outskirts of Indianapolis were released on 19 January 1909, the proposed circuit was to be a two-mile oval track with a three-mile road course located within the infield area; joining the two would create a five-mile (and three feet) combined track-road circuit. The land for the new speedway was about one and a half miles in length and about a half mile wide, covering an area of about 320 acres. 1 “Details of the New Motor Speedway Planned by the Hoosiers,” Motor Age, 21 January 1909, Volume XV No. 3, p. 27. The outside – or oval – track was to be fifty feet wide on the straights and sixty feet wide in the curves, while the inside – or road – track was to be twenty-five feet wide on the straights and thirty-five feet in the turns. The three main grandstands would have a capacity of thirty-five thousand with an additional twenty smaller grandstands, raised ten feet above the track, holding about fifty spectators at various locations along the outer track. The club house of the Indian- apolis Motor Car Club would be located on the grounds, along with buildings to house training quarters and storage for racing teams. -

Comedy of Errors Costs New Glarus

Page 2, Section 2 • Wisconsin State Journal, Monday, July 26,1982 Comedy of errors costs New Glarus 1-0 Sneeberger II 4.2-1-0, Veum c 1-2-0-0, Everson 2b New Glarus outhit Dodgeville, Cottage Grove. Down, 2-1, Held sin- eluding four home runs to rip Arena a triple and Steve Kneebone tied the .iVo Sproul Ib 3-1-1-1, Klttleson ss-P- c I 3-0-0-1, HOME TALENT LEAGUE Lynch 2b-c 3-0-0-1, Skaar p O-O-O-O ™ols M-M-S. 15-9, in a Home Talent League base- (Second-round) gled, advanced to second on a ground- in seven innings. DiPiazza had a per- game when his triple scored Wood. In — Trlnrud Ib 2-1-0-0, KravlK ss j> u EASTERN SECTION out and went to third on a wild pitch fect game through six innings, but the eighth, Craig Anderson tripled to ball game Saturday afternoon, but the Northeast East visitors more than made up the dif- W L W L before scoring on Sdano's single to Jim Roberts ended his no-hit and drive in Rusty Crane, who and sin- Lake Mills ... 3 2 Whitewater 5 0 ^ shutout bid when he singled in the gled, with the winning run. 3 ference by committing, count 'em, 17 Marshall 2 2 Jefferson 3 1 right. After Gary O'Donnell reached 2B - Everson, Johnson. HO - Skoar 5 in 2, Kit- Deerfield 2 2 Utico 3 2 errors, in handing Dodgeville a 15-9 Cottage Grove 2 3 Albion 2 2 on an error and Tim Coulthart's in- sixth and then scored on a sacrafice Waterloo 1 3 Fort Atkinson 2 2 field single loaded the bases, Andy fly by Gary Arnble. -

NASCAR for Dummies (ISBN

spine=.672” Sports/Motor Sports ™ Making Everything Easier! 3rd Edition Now updated! Your authoritative guide to NASCAR — 3rd Edition on and off the track Open the book and find: ® Want to have the supreme NASCAR experience? Whether • Top driver Mark Martin’s personal NASCAR you’re new to this exciting sport or a longtime fan, this insights into the sport insider’s guide covers everything you want to know in • The lowdown on each NASCAR detail — from the anatomy of a stock car to the strategies track used by top drivers in the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series. • Why drivers are true athletes NASCAR • What’s new with NASCAR? — get the latest on the new racing rules, teams, drivers, car designs, and safety requirements • Explanations of NASCAR lingo • A crash course in stock-car racing — meet the teams and • How to win a race (it’s more than sponsors, understand the different NASCAR series, and find out just driving fast!) how drivers get started in the racing business • What happens during a pit stop • Take a test drive — explore a stock car inside and out, learn the • How to fit in with a NASCAR crowd rules of the track, and work with the race team • Understand the driver’s world — get inside a driver’s head and • Ten can’t-miss races of the year ® see what happens before, during, and after a race • NASCAR statistics, race car • Keep track of NASCAR events — from the stands or the comfort numbers, and milestones of home, follow the sport and get the most out of each race Go to dummies.com® for more! Learn to: • Identify the teams, drivers, and cars • Follow all the latest rules and regulations • Understand the top driver skills and racing strategies • Have the ultimate fan experience, at home or at the track Mark Martin burst onto the NASCAR scene in 1981 $21.99 US / $25.99 CN / £14.99 UK after earning four American Speed Association championships, and has been winning races and ISBN 978-0-470-43068-2 setting records ever since. -

Holiday Catalog 2014 – 2015 R Cool Pe D U V S D S

Holiday Catalog 2014 – 2015 r Cool pe D u V S D s ! S EE PAGE 7 Reading for Racers Hot New Titles Most Popular This Year WICKED FAST Racing Through YBrand New from Coastal 181 Life with Bentley Warren by Bones Bourcier THE PEOPLE’S CHAMP One of the most decorated short-track A Racing Life drivers ever, seven-time Oswego Speedway by Dave Darland with Bones Bourcier champion, four-time ISMA champ, two-time The memoir of one of Sprint Car racing ’s most popular Little 500 winner, Indy and Silver Crown and talented racers, a champion in all three of USAC’s star—Bentley Warren is also a self-taught entrepreneur, merry national divisions—Silver Crown, Sprint Cars, and saloon-keeper, tricked-out Harley rider, and overall hell-raiser Midgets—and still winning! Soft cover, 192 pp., with a heart. Soft cover, 272 pp., B&W photos. S-1322: $29.95 32 pp. of B&W and color photos. S-1376: $24.95 DID YOU SEE THAT? A HISTORY OF AUTO RACING Unforgettable Moments in IN NEW ENGLAND Vol. 1 Midwest Open-Wheel Racing by Joyce Standridge A Project of the North East Motor Sports Museum The drama, joy, and sometimes terror that There’s never been a racing book like this. If it was in is open-wheel racing, captured by some of the best photogra - New England, on the boards, the drag strips, or if it’s phers in the country and illuminated by writer and open-wheel about Midgets, Sprints, Modifieds, or Late Models on expert Joyce Standridge. -

County to Enter the Water

A3 Learn more inside on page 10A www.columbiacountyfla.com WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY/SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 7-8, 2020 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $2 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM SUNDAY + PLUS >> FOOTBALL FOOTBALL Program Columbia Indians ‘green lights’ rolls past advance Englewood with first reinstating in play-in win 6B licenses Sean of the South SEE 2A SEE 12A SEE 12A County to Delivering dreams enter the water biz City not capable ment. Construction on a rail of providing for spur at the megasite. the site is underway and the By JAMIE WACHTER primarily [email protected] grant-fund- ed sewer After years of discus- plant sions and planning, the Kraus should be North Florida Mega completed Industrial Park seemed early in 2022. close to becoming a mag- net for industrial develop- WATER continued on 6A VETERANS DAY Elks Lodge hosting TONY BRITT/Lake City Reporter parade in Live Oak Meally Jenkins, Christmas Dream Machine founder and director, arranges toys in the agency’s office Friday Lake City VA holding to the covid-19 pandem- afternoon. The Christmas Dream Machine opened Sunday and has already compiled a list of 100 children to drive-through event ic, the Elks Lodge and a serve this holiday season. Tuesday morning. few other local residents stepped up to make sure Dream Machine begins 32nd year of Christmas giving By JAMIE WACHTER the annual tradition took [email protected] place. By TONY BRITT The Christmas Dream Machine. for providing a building to use this “That was the premise we [email protected] The Christmas Dream Machine, holiday season. -

Indycar | Nascar | Wec | Wrc

ARCA | DTM | FORMULA 1 | IMSA | INDYCAR | NASCAR | WEC | WRC February 5, 2014 | $3.99 ACTION EXPRESS Claims Landmark Daytona Win By René de Boer ™ RACING IS DRAMA See page 5 for Details — get it each week! EXPERIENCE THE WORLD OF AMATEUR MOTORSPORTS AT March 7–9, 2014 | charlotte convention center charlotte, north carolina FEATURED SPEAKERS: RANDY POBST PIRELLI WORLD CHALLENGE CHAMPION ANDY PILGRIM PIRELLI WORLD CHALLENGE CHAMPION 25+ EXPERT-LED RACING SEMINARS 1,000+ AMAZING PRODUCTS AND SERVICES 100+ MUST-SEE EXHIBITS + Road Racing + Solo/Autocross + PDX + Hill Climb + Time Trials + Rally + RallyCross register today at www.msxexpo.com IN ASSOCIATION WITH HELD IN CONJUNCTION WITH SCCA’s NATIONAL CONVENTION! Volume 2 | Issue 2 STARTING February 5, 2014 Motorsport GRID Illustrated News FEATURES inside SCHEDULES 4 RESULTS 5 SNAP SHOTS 6 HOT LAPS 12 on the cover Eventual overall and Prototype winner, the #5 16 NASCAR 18 ACTION 24 INDYCAR Chevrolet, Corvette DP of Joao Barbosa, Christian HALL OF EXPRESS DRIVERS Fittipaldi and Sebastien Bourdais during the Rolex 24 FAME CLAIMS SHOW THEIR at Daytona International Speedway, January 25-26, LANDMARK TALENT AT 2014. Photo by Richard Dole / LAT Photo USA DAYTONA WIN ROLEX 24 this page Crew members run to the #49 Ferrari, 458 Italia, 30 34 GTD of Piergiuseppe Perazzini, Gialuca Roda, UGLY NOISE BIG CHANGES Paolo Ruberti and David Rigon as it runs out of JEREZ F1 WINTER FOR fuel just short of a pit stop during the Rolex 24, TESTING 2014 NASCAR Daytona International Speedway. Photo by Paul Webb / LAT Photo USA FEBRUARY 5, 2014 | MOTORSPORT ILLUSTRATED NEWS | 3 AUTO RACING SCHEDULE February - April, 2014 Weekly Auto Racing Magazine Sales & Marketing Manager: Formula 1 Pro Mazda Championship Southern Whelen Modified Bruce Burns | [email protected] March 16 ............................ -

MISSION STATEMENT A) to Discover, Identify, Gather, Preserve, and Display Newsletter Vol

www.earhs.org MISSION STATEMENT A) To discover, identify, gather, preserve, and display Newsletter Vol. XVI 2019 Ed. #1 documents, records, items, etc. pertaining to eastern auto SIXTY YEARS AGO racing facilities, competitors, personalities or events. As the calendar flipped to 1959, the era of racing on the sand at Daytona Beach ended when Bill France B) To assist writers to publish and/or research articles threw open the gates of the two-and-a-half mile high regarding historical eastern auto racing topics. banked paved Daytona International Speedway. As Our organization collects & displays articles dealing with any the NASCAR drivers prepared for their inaugural eastern auto racing facilities for any racing enthusiast to Daytona '500', working toward Cotton Owens' fast-time enjoy. Please consider either joining our organization or qualifying speed of 143.198 mph, NASCAR and Indy contributing to our projects. vet, Marshall Teague, and his car owner, Chapman Root set their sights on the world closed-course speed MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION record of 176.818 mph, set by Tony Bettenhausen at Monza, Italy during the 'Race of Two Worlds' Indy car appearance there on June 29, 1957. NAME: ______________________________ ADDRESS: __________________________ CITY/STATE/ZIP: _____________________ E-MAIL: _____________________________ AREA OF INTEREST: __________________ _____ $25 SUPPORTER Non-voting supporter of the mission statement of the EARHS. Admission to showroom by appointment. _____ $40 INTERNATIONAL Non-voting international supporter with basic benefits. _____ $250 CORPORATE SUPPORTER Marshall Teague, Chapman Root Sumar Spl., Indy Corporate supporters are non-voting supporters On February 9th Teague reached 171.821 mph at whose contribution to the EARHS will be the wheel of Root's Sumar Streamliner, the same permanently noted in the EARHS showroom. -

50 Years of NASCAR Captures All That Has Made Bill France’S Dream Into a Firm, Big-Money Reality

< mill NASCAR OF NASCAR ■ TP'S FAST, ITS FURIOUS, IT'S SPINE- I tingling, jump-out-of-youn-seat action, a sport created by a fan for the fans, it’s all part of the American dream. Conceived in a hotel room in Daytona, Florida, in 1948, NASCAR is now America’s fastest-growing sport and is fast becoming one of America’s most-watched sports. As crowds flock to see state-of-the-art, 700-horsepower cars powering their way around high-banked ovals, outmaneuvering, outpacing and outthinking each other, NASCAR has passed the half-century mark. 50 Years of NASCAR captures all that has made Bill France’s dream into a firm, big-money reality. It traces the history and the development of the sport through the faces behind the scene who have made the sport such a success and the personalities behind the helmets—the stars that the crowds flock to see. There is also a comprehensive statistics section featuring the results of the Winston Cup series and the all-time leaders in NASCAR’S driving history plus a chronology capturing the highlights of the sport. Packed throughout with dramatic color illustrations, each page is an action-packed celebration of all that has made the sport what it is today. Whether you are a die-hard fan or just an armchair follower of the sport, 50 Years of NASCAR is a must-have addition to the bookshelf of anyone with an interest in the sport. $29.95 USA/ $44.95 CAN THIS IS A CARLTON BOOK ISBN 1 85868 874 4 Copyright © Carlton Books Limited 1998 Project Editor: Chris Hawkes First published 1998 Project Art Editor: Zoe Maggs Reprinted with corrections 1999, 2000 Picture Research: Catherine Costelloe 10 9876 5 4321 Production: Sarah Corteel Design: Graham Curd, Steve Wilson All rights reserved. -

Donald Regan U.S. Aid 1 Counters

poUiT.''"''.' 1 -ti?'' ■ J 24 - THE HERALD, Sat.. Oct 10. 1981 Donald Regan Coventry woman's stage lives... page Treasury secretary is selling Reagonomics to business By Mary Beth Franklin balanced by the end of fiscal 1984 when increased ■If?"', Manchester, Conn. UPl Reporter military spending w ill be in full swing and individual tax Cold tonight; “Business has been asking, rates w ill be cut permanently by being “ indexed” to the Mon., Oct. 12, 1981 WASHINGTON — Treasury Secretary Donald Regan, rate of inflation. sunny Tuesday who President Reagan jokingly calls “ cousin" because screaming, yelling ‘set ns free ANNOYED BY THE economic “ nay-sayers,” Regan 25 Cents — see page 2 of the similarities of their names, is a man accustomed from high taxes fo r years. We’ve snorted, “ Whenever one of those gurus say something, to winning. it’s like it’s written in stone... Well, we have as much Mpralb When the chances of passing the president's mam done it. Notv, where’s their chance of being'right as they do.” moth tax cut bill before the congressional August recess response? Regan is an aggressive man. Patience is not high on grew dim, Regan told an aide flatly, "I don’t lose." — Donald Regan his list of virtues. Then, the man who initially was considered the most He said he likes his job, but it is far from fun. The politically naive of Reagan's Cabinet proceeded to put cumbersome process of government is the most together the crucial compromises that ted to final frustrating part. “ I could turn this economy around if passage of the biggest tax cut in history.