Doctor of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

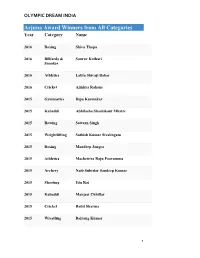

Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name

OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name 2016 Boxing Shiva Thapa 2016 Billiards & Sourav Kothari Snooker 2016 Athletics Lalita Shivaji Babar 2016 Cricket Ajinkya Rahane 2015 Gymnastics Dipa Karmakar 2015 Kabaddi Abhilasha Shashikant Mhatre 2015 Rowing Sawarn Singh 2015 Weightlifting Sathish Kumar Sivalingam 2015 Boxing Mandeep Jangra 2015 Athletics Machettira Raju Poovamma 2015 Archery Naib Subedar Sandeep Kumar 2015 Shooting Jitu Rai 2015 Kabaddi Manjeet Chhillar 2015 Cricket Rohit Sharma 2015 Wrestling Bajrang Kumar 1 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2015 Wrestling Babita Kumari 2015 Wushu Yumnam Sanathoi Devi 2015 Swimming Sharath M. Gayakwad (Paralympic Swimming) 2015 RollerSkating Anup Kumar Yama 2015 Badminton Kidambi Srikanth Nammalwar 2015 Hockey Parattu Raveendran Sreejesh 2014 Weightlifting Renubala Chanu 2014 Archery Abhishek Verma 2014 Athletics Tintu Luka 2014 Cricket Ravichandran Ashwin 2014 Kabaddi Mamta Pujari 2014 Shooting Heena Sidhu 2014 Rowing Saji Thomas 2014 Wrestling Sunil Kumar Rana 2014 Volleyball Tom Joseph 2014 Squash Anaka Alankamony 2014 Basketball Geetu Anna Jose 2 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2014 Badminton Valiyaveetil Diju 2013 Hockey Saba Anjum 2013 Golf Gaganjeet Bhullar 2013 Athletics Ranjith Maheshwari (Athlete) 2013 Cricket Virat Kohli 2013 Archery Chekrovolu Swuro 2013 Badminton Pusarla Venkata Sindhu 2013 Billiards & Rupesh Shah Snooker 2013 Boxing Kavita Chahal 2013 Chess Abhijeet Gupta 2013 Shooting Rajkumari Rathore 2013 Squash Joshna Chinappa 2013 Wrestling Neha Rathi 2013 Wrestling Dharmender Dalal 2013 Athletics Amit Kumar Saroha 2012 Wrestling Narsingh Yadav 2012 Cricket Yuvraj Singh 3 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2012 Swimming Sandeep Sejwal 2012 Billiards & Aditya S. Mehta Snooker 2012 Judo Yashpal Solanki 2012 Boxing Vikas Krishan 2012 Badminton Ashwini Ponnappa 2012 Polo Samir Suhag 2012 Badminton Parupalli Kashyap 2012 Hockey Sardar Singh 2012 Kabaddi Anup Kumar 2012 Wrestling Rajinder Kumar 2012 Wrestling Geeta Phogat 2012 Wushu M. -

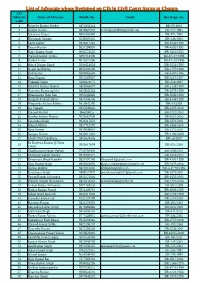

List of Advocate Whose Registred on CIS in Civil Court Saran at Chapra CIS Advocate Name of Advocate Mobile No

List of Advocate whose Registred on CIS in Civil Court Saran at Chapra CIS Advocate Name of Advocate Mobile No. Email Bar Regn. No. Code 1 Birendra Kumar Pandey 9470481114 BR-55/1992 2 Gunjan Verma 9934921847 [email protected] BR-733/1993 3 Mazharul Haque 9905403496 BR-883/1993 4 Bholanath Sharma 9546907435 BR-346/1994 5 Sunil Kumar 9835611348 BR-5740/1995 6 Pawan Kumar 9631594900 BR-4363/1995 7 Rajiv Kumar Singh 8002574542 BR-5310/1995 8 Pramod Kumar Verma 8651814306 BR-10127/1996 9 Pankaj Verma 9835075266 BR-10128/1996 10 Ashok Kumar Singh 9304014624 BR-2631/1996 11 Gopal Jee Pandey 9852088205 BR-2177/1996 12 Kishun Rai 9097962645 BR-8407/1996 13 Renu Kumari 9835268997 BR-3317/1997 14 Tripurari Singh 8292621173 BR-316/1997 15 Birendra Kumar Sharma 8409066877 BR-2124/1998 16 Narendra Kumar pandey 9430945334 BR-3879/1999 17 Dharmendra Nath Sah 9905266646 BR-6243/1999 18 Durgesh Prakash Bihari 9431406306 BR-4144/1999 19 Bhupendra Mohan Mishra 9430945395 BR-68/2009 20 Jay Prakash 9835649645 BR-2397/2010 21 Praveen Kumar 966194025 BR-3132/2003 22 Kundan Kumar Sharma 9525661909 BR-2023/2002 23 Satyendra Singh 9934217633 BR-2870/2001 24 Rakesh Milton 8507718379 BR-1861/2005 25 Ajay Kumar 9939849041 BR-1372/2001 26 Sanjeev Kumar 9430011002 BR-1196/2000 27 Shashi Nath Upadhyay 9430624506 BR-26/1999 Dr Rajeewa Kumar @ Pintu 28 9835617674 BR-951/2000 Tiwari 29 Shashiranjan Kumar Pathak 7739791080 BR-3590/2001 30 Mritunjay Kumar Pandey 9835843533 BR-3316/2003 31 Dineshwer SIngh Kaushik 9931807349 [email protected] BR-4761/1999 32 Ajay -

Athletics, Badminton, Gymnastics, Judo, Swimming, Table Tennis, and Wrestling

INDIVIDUAL GAMES 4 Games and sports are important parts of our lives. They are essential to enjoy overall health and well-being. Sports and games offer numerous advantages and are thus highly recommended for everyone irrespective of their age. Sports with individualistic approach characterised with graceful skills of players are individual sports. Do you like the idea of playing an individual sport and be responsible for your win or loss, success or failure? There are various sports that come under this category. This chapter will help you to enhance your knowledge about Athletics, Badminton, Gymnastics, Judo, Swimming, Table Tennis, and Wrestling. ATHLETICS Running, jumping and throwing are natural and universal forms of human physical expression. Track and field events are the improved versions of all these. These are among the oldest of all sporting competitions. Athletics consist of track and field events. In the track events, competitions of races of different distances are conducted. The different track and field events have their roots in ancient human history. History Ancient Olympic Games are the first recorded examples of organised track and field events. In 776 B.C., in Olympia, Greece, only one event was contested which was known as the stadion footrace. The scope of the games expanded in later years. Further it included running competitions, but the introduction of the Ancient Olympic pentathlon marked a step towards track and field as it is recognised today. There were five events in pentathlon namely—discus throw, long jump, javelin throw, the stadion foot race, and wrestling. 2021-22 Chap-4.indd 49 31-07-2020 15:26:11 50 Health and Physical Education - XI Track and field events were also present at the Pan- Activity 4.1 Athletics at the 1960 Summer Hellenic Games in Greece around 200 B.C. -

Technical Handbook

TECHNICAL HANDBOOK CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. List of Sports in Khelo India University Games (KIUG – 2020) 4 3. Player Qualification Criteria 5 4. Guidelines for Appointment of Coaches and Managers 7 5. Venues at a Glance 8 6. Sports Schedule 9 7. Medals at Stake 10 8. Contact Details of OC – KIUG & Sports Competition Managers 11 I. Archery 12 II. Athletics 17 III. Badminton 22 IV. Basketball 26 V. Boxing 30 VI. Fencing 34 VII. Football 38 VIII. Hockey 45 IX. Judo 49 X. Kabaddi 53 XI. Rugby 57 XII. Swimming 61 XIII. Table Tennis 65 XIV. Tennis 69 XV. Volleyball 73 XVI. Weightlifting 77 XVII. Wrestling 81 INTRODUCTION The “Khelo India” – National Program for Development of Sports was revamped. Khelo India has the following twelve verticals: Under the vertical Annual Sports Competitions, the 1st Khelo India Games were organized in 2018. The 2nd edition was held in 2019 which saw participation of athletes from across India in U-17 & U-21 age categories. The 3rd Khelo India Youth Games were organized in Guwahati from 10th January – 22nd January 2020. This year, the University Games have been planned to be held separately at Bhubaneswar in association with the Govt. of Odisha, Association of Indian Universities (AIU) and KIIT University from 22nd Feb to 1st Mar 2020. These games will be called “Khelo India University Games, Odisha 2020”. Concept Khelo India University Games (KIUG – 2020) will be organized in Under-25 age group (Men & Women). The competition will be amongst the top Universities in 17 sports disciplines from 22nd February – 1st March 2020 at Bhubaneswar, Odisha. -

Multidisciplinary Case Studies

STUDY MATERIAL PROFESSIONAL PROGRAMME MULTIDISCIPLINARY CASE STUDIES MODULE 3 PAPER 8 i © THE INSTITUTE OF COMPANY SECRETARIES OF INDIA Disclaimer : Although due care and diligence have been taken in preparation of this Study Material , the Institute shall not be responsible for any loss or damage, resulting from any action taken on the basis of the contents of this Study Material. Anyone wishing to act on the basis of the material contained herein should do so after cross checking with the original source. TIMING OF HEADQUARTERS Monday to Friday Office Timings – 9.00 A.M. to 5.30 P.M. Public Dealing Timings Without financial transactions – 9.30 A.M. to 5.00 P.M. With financial transactions – 9.30 A.M. to 4.00 P.M. Phones 011-45341000 Fax 011-24626727 Website www.icsi.edu E-mail [email protected] Laser Typesetting by AArushi Graphics, Prashant Vihar, New Delhi, and Printed at M P Printers/January 2019 ii PROFESSIONAL PROGRAMME Module 3 Paper 8 Multidisciplinary Case Studies (Max Marks 100) SYLLABUS Objective To test the students in their theoretical, practical and problem solving abilities. Detailed Contents Case studies mainly on the following areas: 1. Corporate Laws including Company Law 2. Securities Laws 3. FEMA and other Economic and Business Legislations 4. Insolvency Law 5. Competition Law 6. Business Strategy and Management 7. Interpretation of Law 8. Governance Issues. iii CONTENTS MULTIDISCIPLINARY CASE STUDIES S.No. Lesson Tittle Page No. 1. Corporate Laws including Company Law 1 2. Securities Laws 107 3. FEMA and other Economic and Business Legislations 123 4. -

400M Hurdles the Man-Killer Event

400M HURDLES THE MAN-KILLER EVENT A TECHNICAL GUIDE FOR COACHES & ATHLETES OUTS ORK WITH 111 SAMPLE W ROHINTON MEHTA FOREWORD BY P. T. USHA INDIA MASTERS ATHLETICS 400M HURDLES THE MAN-KILLER EVENT A TECHNICAL GUIDE FOR COACHES & ATHLETES ROHINTON MEHTA India Masters Athletics © Dr. Rohinton Mehta Publisher : India Masters Athletics Printed and Computer set by Union Press, Mumbai No part of this Publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the Author, who can be contacted at 9820347787 or at [email protected] This book is dedicated to the Athletics Federation of India (AFI) and the Sports Authority of India (SAI) for nurturing and developing Track & Field talent in India. CONTENTS FOREWORD iv PREFACE vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS viii LIST OF TABLES x GLOSSARY xi Chapter 1 : Introduction: The 400m Hurdles 1 Chapter 2 : Hurdling Ability 7 Chapter 3 : Overcoming Fear of the Hurdles 20 Chapter 4 : 400m Hurdles Racing Experience 32 Chapter 5 : Speed (Alactic Training) 35 Chapter 6 : Speed Endurance (Lactic Training) 39 Chapter 7 : Aerobic Endurance (Cardiovascular Training) 44 Chapter 8 : Rhythm and the 400m Hurdles 47 Chapter 9 : Training Psychology 55 Chapter 10 : Flexibility 67 Chapter 11 : Strength, Resistance & Core Training 72 Chapter 12 : Nutrition & Rest 83 Chapter 13 : Running Equivalent (RE) or Cross Training 91 Chapter 14 : Structured Warm-up & Cool-down 95 Chapter 15 : Correction of Common Faults in Hurdling 104 Chapter 16 : 111 Workouts for 400m Hurdles 114 BIBLIOGRAPHY 144 INDEX 166 P. T. USHA Usha School of Athletics Kinalur, Ballussery, Kozhikode 673 612, Kerala, India. -

MP Ed Semester 3Rd Paper – 16MPE23D1 Science of Coaching Games -Basketball

MAHARSHI DAYANAND UNIVERSITY ROHTAK DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION Scheme of examination for M.P.Ed. Under CBCS w.e.f. Session 2016-17 M.P.ED 1st Semester Paper Code Nomenclature Contact hours Credits Max. (L+T+P) marks 16MPE21C1 Scientific Principles of (4: 1: 0 ) 05 80+20 Sports Training 16MPE21C2 Research Process in (4: 1: 0 ) 05 80+20 Physical Education 16MPE21C3 Sports Medicine (4: 1: 0 ) 05 80+20 16MPE21C4 Sports Psychology (4: 1: 0 ) 05 80+20 16MPE21C5 Teaching lesson – (0: 0: 6) 03 100 Games 16MPE21C6 Teaching Lesson- (0: 0: 6 ) 03 100 Athletics Total Credit= 26 Activities to be taken up during 1st Semester A. Games: - Basketball, Korfball, Hockey, Handball, Swimming and Judo. B .Athletics: - Sprints, Long Jump, Pole-vault, Hurdles, Javelin & Discus-throw. Note: - The practical classes shall be held as per the scheme & Schedule of each semester. The final practical examinations for each semester shall be conducted by external & internal examiners at the end of each semester. Minimum Five students must opt an optional paper to run the options. M.P.ED 2nd Semester Paper Code Nomenclature Contact hours Credits Max. Marks (L+T+P) (External+Internal) 16MPE22C1 Applied Statistics in (4: 1: 0 ) 05 80+20 Physical Education and Sports 16MPE22C2 Sports Bio-Mechanics (4: 1: 0 ) 05 80+20 and Kinesiology 16MPE22C3 Physiology of (4: 1: 0 ) 05 80+20 Exercise 16MPE22C4 Teaching lesson – ( 0: 0: 6) 03 100 Games 16MPE22C5 Teaching Lesson- ( 0: 0: 6) 03 100 Athletics Paper is to be chosen 03 from the basket of open elective papers provided by the University Paper is to be chosen 02 from the basket of foundation elective papers provided by the University Total Credit= 26 Activities to be taken up during 2nd Semester A- Games:- Volleyball, Kabaddi, Football, Boxing, & Wrestling. -

Interim Arbitral Award Court of Arbitration for Sport

CAS 2014/A/3759 Dutee Chand v. Athletics Federation of India (AFI) & The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) INTERIM ARBITRAL AWARD delivered by the COURT OF ARBITRATION FOR SPORT sitting in the following composition: President: The Hon. Justice Annabelle Claire Bennett AO, Federal Court of Australia, Sydney, Australia Arbitrators: Prof. Richard H. McLaren, attorney-at law in London, Canada _ Dr Hans Nater, attorney-at-law in Zurich, Switzerland Ad hoc Clerk: Mr Edward Craven, barrister in London, United Kingdom in the arbitration between Ms Dutee Chand, Odisha, India Represented by Mr James Bunting, Mr Carlos Sayao, and Hon. Morris J. Fish Q.C. of Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg LLP in Toronto, Canada Appellant and Athletics Federation of India (AFI), New Delhi, India First Respondent The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), Monaco Cedex Represented by Mr Jonathan Taylor and Ms Elizabeth Riley of Bird & Bird LLP in London, United Kingdom Second Respondent CAS 2014/A/3759 Dutee Chand v. AFI & TAAP -Page 2 I. PARTIES 1. Dutee Chand (the "Athlete") is a 19 year-old female athlete of Indian nationality. During her career to date she has won a number of national junior athletics events in India. In addition, she won gold medals in the women's 200 metres sprint and the women's 4 x 400 metre sprint relay at the Asian Junior Track and Field Championships in Taipei in May 2014. 2. The Athletics Federation of India (the "AFI") is the national governing body for the sport of athletics in India. 3. The International Association of Athletics Federations (the "IAAF") is the international governing body of the sport of athletics, recognised as such by the International Olympic Committee. -

[email protected]

People often ask me, The world can be changed by some thoughtful & committed “How do I dene citizens, never doubt them. happiness?” Well, I define happiness as a posive state of mind, which gets mulplied when I take acons to spread it to others. I believe, happiness is never readymade. Neither is happiness As they say, the only thing constant in this world is CHANGE. And though limited to achieving big things in life. There are millions of this change may be iniated by one person, it always needs a collecve smaller things in life, which can spread happiness. effort from many people to make it successful. An effort achieves new But, it needs a constant effort to create those many moments, heights and becomes ‘mission successful’, when people from all walks of which we can call ‘happy moments’. It gives me profound life, make it their own personal mission. pleasure to admit that under the incredible guidance of And that’s the philosophy that has been guiding Sonalika Group for over Dr. Deepak Mial and under the banner of Sonalika CSR, 4 decades now. The company has constantly been striving to bring a I experience a deep urge to share this happiness and extend change in the life of farmers. And, with acve parcipaon of its support to those secons of society which deserve it the most. employees and associates, Sonalika Group has been able to make a holisc contribuon to the agricultural community as a whole. This gives At Sonalika CSR, we are lucky to get an opportunity to touch me enough confidence to call Sonalika as ‘one of the major drivers of many lives. -

Bulletin TAS CAS Bulletin

Bulletin TAS CAS Bulletin 2015/2 TRIBUNAL ARBITRAL DU SPORT/COURT OF ARBITRATION FOR SPORT __________________________________________________________________ Bulletin TAS CAS Bulletin 2015/2 Lausanne 2015 Table des matières/Table of Contents Message du Secrétaire Général du TAS/Message from the CAS Secretary General Articles et commentaires/Articles and Commentaries ......................................................................... 6 Applicable law in football-related disputes ......................................................................................... 7 - The relationship between the CAS Code, the FIFA Statutes and the agreement of the parties on the application of national law - ......................................................................................................... Ulrich Haas .............................................................................................................................................. 7 A brief review of recent CAS Jurisprudence relating to football transfers .................................. 18 Mark A. Hovell ........................................................................................................................................... Mediation of sports-related disputes: facts, statistics and prospects for CAS mediation procedures .............................................................................................................................................. 24 Despina Mavromati .................................................................................................................................. -

VACANCY No.16020311313 Roll No

VACANCY No.16020311313 Roll No. Name Father Name DOB community 1 AASHUTOSH TIWARI RAMESH CHANDRA TIWARI 29-09-1982 GEN 2 ABHA MALIK JITENDRA MALIK 29-05-1989 GEN 3 ABHILASHA SINGH PRAMOD KUMAR SINGH 10-07-1988 GEN 4 ABHINAV VIKRAM BALESHWAR SINGH 27-09-1983 GEN 5 ABHISHEK SINGH PRAHLAD SINGH 18-02-1987 GEN 6 ABHISHEK UPADHYAY BANARASI UPADHYAY 20-12-1988 GEN 7 ABHISHEK KUMAR SINGH ASHOK KUMAR SINGH 02-08-1987 GEN 8 ABHISHEK PRATAP SINGH RAM SINGH 20-04-1986 GEN 9 ABUSAD AHAMAD IMTIYAZ AHAMAD 13-05-1991 GEN 10 AJAY KUMAR MISHRA NIRBHAY NATH MISHRA 10-03-1988 GEN 11 AJAY KUMAR MISHRA NIRBHAY NATH MISHRA 10-03-1988 GEN 12 AJAY VEERBIKRAM SINGH JAY SINGHBAHADUR SINGH 12-09-1988 GEN 13 AJEET KUMAR RAI SAHAJA NAND RAI 12-07-1981 GEN 14 AJIT KUMAR TIWARI SURENDRA NATH TIWARI 09-07-1984 GEN 15 ALKA BAJPAI SUSHIL KUMAR BAJPAI 30-12-1987 GEN 16 ALKA TIWARI AWADHESH TIWARI 03-06-1988 GEN 17 ALKA DNYANESHWAR GHODAKE DNYANESHWAR RAMCHANDRA GHODAKE 01-01-1987 GEN 18 ALOK CHAND SATYA NARAYAN GUPTA 26-08-1988 GEN 19 ALOK MISHRA TRIBHUVAN MISHRA 25-08-1984 GEN 20 ALOK SHARMA MADHAVA PRASAD SHARMA 05-10-1979 GEN 21 ALOK TIWARI AWADHESH TIWARI 05-09-1980 GEN 22 ALOK KUMAR SINGH JANARDAN SINGH 01-10-1986 GEN 23 ALOK KUMAR TIWARI KAPIL DEV TIWARI 10-02-1989 GEN 24 ALOK RANJAN SRIVASTAVA VIJAY PRATAPNARAYAN SRIVASTAVA 11-07-1988 GEN 25 AMAR KUMAR CHOUDHARY RAMANAND CHOUDHARY 02-05-1985 GEN 26 AMARENDRA KUMAR PANDEY RAMESH PRASAD PANDEY 01-09-1985 GEN 27 AMARENDRA KUMAR SRIVASTAVA ISHWAR SHARAN SRIVASTAVA 01-07-1981 GEN 28 AMIT PANDEY PAWAN KUMAR PANDEY 27-01-1992 -

Current Affairs July 2018 PDF Capsule

Current Affairs Study PDF Current Affairs July 2018 PDF Capsule CCent Affairs for Competitive Exam 1 | Page Follow Us - FB.com/AffairsCloudOfficialPage Copyright 2018 @ AffairsCloud.Com Current Affairs Study PDF CURRENT AFFAIRS FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM CONTENTS INDIAN AFFAIRS ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Cabinet Approvals ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Schemes ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 Launches & Inaugurations ........................................................................................................................... 12 Festival ......................................................................................................................................................... 31 Other News Related to Indian Affairs ......................................................................................................... 32 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS ........................................................................................................................ 56 VISIT ............................................................................................................................................................... 63 Indian Visits ................................................................................................................................................