SECRETS of PT USHA John Samuel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

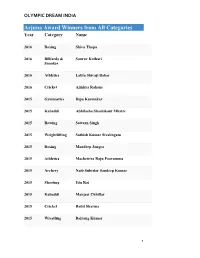

Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name

OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name 2016 Boxing Shiva Thapa 2016 Billiards & Sourav Kothari Snooker 2016 Athletics Lalita Shivaji Babar 2016 Cricket Ajinkya Rahane 2015 Gymnastics Dipa Karmakar 2015 Kabaddi Abhilasha Shashikant Mhatre 2015 Rowing Sawarn Singh 2015 Weightlifting Sathish Kumar Sivalingam 2015 Boxing Mandeep Jangra 2015 Athletics Machettira Raju Poovamma 2015 Archery Naib Subedar Sandeep Kumar 2015 Shooting Jitu Rai 2015 Kabaddi Manjeet Chhillar 2015 Cricket Rohit Sharma 2015 Wrestling Bajrang Kumar 1 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2015 Wrestling Babita Kumari 2015 Wushu Yumnam Sanathoi Devi 2015 Swimming Sharath M. Gayakwad (Paralympic Swimming) 2015 RollerSkating Anup Kumar Yama 2015 Badminton Kidambi Srikanth Nammalwar 2015 Hockey Parattu Raveendran Sreejesh 2014 Weightlifting Renubala Chanu 2014 Archery Abhishek Verma 2014 Athletics Tintu Luka 2014 Cricket Ravichandran Ashwin 2014 Kabaddi Mamta Pujari 2014 Shooting Heena Sidhu 2014 Rowing Saji Thomas 2014 Wrestling Sunil Kumar Rana 2014 Volleyball Tom Joseph 2014 Squash Anaka Alankamony 2014 Basketball Geetu Anna Jose 2 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2014 Badminton Valiyaveetil Diju 2013 Hockey Saba Anjum 2013 Golf Gaganjeet Bhullar 2013 Athletics Ranjith Maheshwari (Athlete) 2013 Cricket Virat Kohli 2013 Archery Chekrovolu Swuro 2013 Badminton Pusarla Venkata Sindhu 2013 Billiards & Rupesh Shah Snooker 2013 Boxing Kavita Chahal 2013 Chess Abhijeet Gupta 2013 Shooting Rajkumari Rathore 2013 Squash Joshna Chinappa 2013 Wrestling Neha Rathi 2013 Wrestling Dharmender Dalal 2013 Athletics Amit Kumar Saroha 2012 Wrestling Narsingh Yadav 2012 Cricket Yuvraj Singh 3 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2012 Swimming Sandeep Sejwal 2012 Billiards & Aditya S. Mehta Snooker 2012 Judo Yashpal Solanki 2012 Boxing Vikas Krishan 2012 Badminton Ashwini Ponnappa 2012 Polo Samir Suhag 2012 Badminton Parupalli Kashyap 2012 Hockey Sardar Singh 2012 Kabaddi Anup Kumar 2012 Wrestling Rajinder Kumar 2012 Wrestling Geeta Phogat 2012 Wushu M. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1844 , 09/04/2018 Class 19 2271711 24

Trade Marks Journal No: 1844 , 09/04/2018 Class 19 2271711 24/01/2012 SHAKUNTLA AGARWAL trading as ;AGARWAL TIMBER TRADERS VILLAGE UDAIPUR GOLA ROAD LAKHIMPUR KHERI 262701 U.P MANUFACTURER & TRADER Address for service in India/Attorney address: ASHOKA LAW OFFICE ASHOKA HOUSE 8, CENTRAL LANE, BENGALI MARKET, NEW DELHI - 110 001. Used Since :01/04/1995 DELHI PLYBOARD,HARDBOARD,FLUSHDOOR(WOOD),MICA,PLY,BLOCKBOARDS,INCLUDED IN THIS CLASS THIS IS CONDITION OF REGISTRATION THAT BOTH/ALL LABELS SHALL BE USED TOGETHER.. 2244 Trade Marks Journal No: 1844 , 09/04/2018 Class 19 2325042 02/05/2012 SH. SUNIL MITTAL trading as ;M/S. SHRI RAM INDUSTRIES VILLAGE BRAMSAR, TEHSIL RAWATSAR, DISTT.- HANUMAN GARH, RAJASTHAN - 335524 MANUFACTURERS AND MERCHANTS Address for service in India/Agents address: DELHI REGISTRATION SERVICES 85/86, GADODIA MARKET, KHARI BAOLI, DELHI - 110 006 Used Since :01/04/2010 AHMEDABAD PLASTER OF PARIS. 2245 Trade Marks Journal No: 1844 , 09/04/2018 Class 19 2338662 28/05/2012 ROHIT PANDEY 71-72, POLO GROUND, GIRWA, UDAIPUR (RAJASHTAN) . PROPRIETORSHIP FIRM Address for service in India/Attorney address: RAJEEV JAIN 17, BHARAT MATA PATH, JAMNA LAL BAJAJ MARG, C-SCHEME, JAIPUR - 302 001- RAJASTHAN Used Since :19/12/2000 AHMEDABAD MINERALS AND MANUFACTURER OF TILES, BLOCKS AND SLABS OF GRANITES, MARBLES, AGGLOMERATED MARBLES. 2246 Trade Marks Journal No: 1844 , 09/04/2018 Class 19 I.MICRO LIMESTONE Priority claimed from 25/01/2012; Application No. : MI2012C000763. ;Italy 2369681 25/07/2012 ITALCEMENTI S.p.A VIA CAMOZZI 124 24121 BERGAMO ITALY MANUFACTURERS AND MERCHANTS A COMPANY ORGANIZED AND EXISTING UNDER THE LAWS OF ITALY. -

(Department of Sports) Lok Sabha Starred Question No

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF YOUTH AFFAIRS & SPORTS (DEPARTMENT OF SPORTS) LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. †*85 TO BE ANSWERED ON 08.02.2018 Encouraging Female Players †*85. SHRI BHOLA SINGH: Will the Minister of YOUTH AFFAIRS AND SPORTS be pleased to state: (a) whether women from various States of the North Eastern Region (NER) have brought laurels to the country in the field of sports; (b) if so, the details thereof along with the schemes being implemented by the Government to encourage female players in the region; (c) whether the Government has formulated any action plan to identify and nurture the talent of young sportpersons of the rural areas of NER; and (d) if so, the details thereof? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) FOR YOUTH AFFAIRS & SPORTS {COL. RAJYAVARDHAN RATHORE (RETD.)} (a) to (d) A statement is laid on the Table of the House. STATEMENT REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PARTS (a) TO (d) OF THE LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. †*85 FOR 08.02.2018 ASKED BY SHRI BHOLA SINGH, MP, REGARDING ENCOURAGING FEMALE PLAYERS. (a) Yes, Madam. (b) The most prominent women sportspersons from the North Eastern Region (NER), who have brought laurels to the country in different sports disciplines are Ms. M C Mary Kom (Boxing), Ms. Dipa Karmakar (Gymnastics), Ms. L Sarita Devi (Boxing), Ms. N. Kunjarani Devi (Weightlifting), Ms. Anita Chanu (Weightlifting), Ms. Lily Chanu (Archery), Ms. L Bombayla Devi (Archery), Ms. O Bem Bem Devi (Football), etc. Sports promotional Schemes being implemented by the Ministry of Youth Affairs & Sports cater to the entire population of the country, both male and female, including women from NER. -

Fifth Term, Examination, 2019

SR.NO.AER/2019/449 --------------------- UNIVERSITY OF DELHI ------------------- LL.B. FIFTH TERM EXAMINATION, 2019. ----------------------------------- The result of the following candidates who appeared at the Vth Term LL.B. Examination held in November/December, 2019 is shown hereunder :- Marks obtained in the Terms concerned have been indicated against the candidates who have passed the Examination. The paper/s shown against the names indicates that the candidate/s have passed in the paper/s concerned. ER- Essential reappear. ---------------------------------------------------------------------- Roll No. Name of Candidate T E R M S I III V (Out of 500)(Out of 500) (Out of 500) ---------------------------------------------------------------------- LAW CENTRE-I ------------ 142774 NAVEEN KUMAR SINGH 291 270 RAMA SHANKAR SINGH 142878 PRITAM SINGH Absent LB-501,502 SATBIR SINGH 143004 SALMAN TEMURI LB-301, LB-501,502, HASHIM TEMURI 302 503,5037 150821 ABHISHEK GAUTAM 259 LB-501,502, RAKESH GAUTAM 5031,5037 150953 ARVIND PANDEY LB-501,502, RAJIV LOCHAN PANDEY 503,5031 150999 BHARAT BHATI 253 271 GAJRAJ SINGH BHATI 151062 DISHANT SEHRAWAT 257 LB-501,502, VIJAY PAL 503,5037 151075 FARHAN KHAN 246 302 LB-501 F.Z. MURAD 151107 GURDEEP SINGH 271 257 281 NARENDER SINGH 151131 ILAYARAJA K 255 242 LB-501,502, KADARKARAIYANDI P 503,5034 151246 MANOJ KUMAR LB-302 LB-501,503, LAKHPAT SINGH 5033 Contd.P/2 - 2 - UNIVERSITY OF DELHI ------------------- LL.B. FIFTH TERM EXAMINATION, 2019. ----------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------- Roll No. Name of Candidate T E R M S I III V (Out of 500)(Out of 500) (Out of 500) ---------------------------------------------------------------------- LAW CENTRE-I ------------ 151257 MEGHNA CHOUDHARY 309 PARAS RAM CHOUDHARY 151369 PRAMOD KUMAR SHARMA Failed LB-302 259 SANJAI KUMAR SHARMA 151438 RAJIV KUMAR KESHRI Absent LB-302, LB-501,502, DEV NARAYAN KESHRI 3031 503,5031 151496 S. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR th THURSDAY,THE 16 AUGUST,2012 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 1 TO 45 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 46 TO 47 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 48 TO 60 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL / 61 TO 78 REGISTRAR (ORGL.) / REGISTRAR (ADMN.) / JOINT REGISTRARS (ORGL.) 16.08.2012 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 HON'BLE THE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SANJAY KISHAN KAUL HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE RAJIV SHAKDHER AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS 1. W.P.(C) 3238/2011 HDFC BANK CHETNA BHALLA CM APPL. 6830/2011 Vs. SATPAL SINGH BANKSHI AT 3.45 PM 16.08.2012 COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-1) HON'BLE THE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE RAJIV SAHAI ENDLAW FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS 1. W.P.(C) 9037/2011 M.S.FRANK RAJAT SINGH CM APPL. 20336/2011 Vs. DELHI UNIVERSITY AND ORS CM APPL. 8776/2012 AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS 2. LPA 591/2008 NARAIN SINGH AND ANR. MR.ANAND YADAV,NS DALAL Vs. FINANCIAL COMMISSIONER AND ORS. FOR DIRECTIONS 3. CO.APP. 20/2008 RAJIV SARIN (EX-MANAGEMENT) K.C.NANDA,AJAY Vs. OFFICIAL LIQUIDATOR AND ORS VERMA,V.N.SHARMA,SR NARAYAN,S.K.LUTHRA AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS FOR FINAL HEARING 4. LPA 482/2012 CHAMAN KUMAR SOUMYAJIT PANI,MJS RUPAL CM APPL. 11202/2012 Vs. UNIVERSITY OF DELHI AND CM APPL. 11221/2012 ANR 16.08.2012 COURT NO.2 (DIVISION BENCH-2) HON'BLE MR. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Athletics A) Vikas Gowda

S.N. List of Athletes Discipline Wise under TOP Scheme (as of 31.07.2015) Athletics 1 a) Vikas Gowda - Men’s Discus Throw 2 b) Seema Antil –Women’s Discus Throw 3 c) Arpinder Singh – Men’s Triple Jump 4 e) Khushbir Kaur - 20km Racewalking 5 f) K.T. Irfan - 20km Racewalking 6 d) Inderjeet Singh - Men's Shot Put 7 g) Priyanka Pawar - 4x400m Women Relay 8 h) Tintu Luka - 4x400m Women Relay 9 i) Debashree Majumdar - 4x400m Women Relay 10 j) M.R. Poovamma - 4x400m Women Relay 11 k) Anilda Thomas - 4x400m Women Relay 12 l) Ashwini Akkunji - 4x400m Women Relay 13 m) Jauna Murmu - 4x400m Women Relay 14 n) Sini Jose - 4x400m Women Relay 15 o) Mandeep Kaur - 4x400m Women Relay 16 p) Chavi Sharawat - 4x400m Women Relay 17 q) Anju Thomas - 4x400m Women Relay 18 r) Nirmala - 4x400m Women Relay 19 s) Arpitha M. - 4x400m Women Relay 20 t) K. Ganapathy - 20km Racewalking 21 u) Manish Rawat - 20km Racewalking 22 v) Sandeep Kumar - 20km Racewalking 23 w) Devender Singh - 20km Racewalking 24 x) Navjeet Kaur - Women's Discus Throw 25 y) Gurmeet Singh - 20km Race Walking 26 z) Jisna Mathew - 4x400m Women Relay Archery (16 athletes) 27 a) Tarundeep Rai - Men Archery 28 b) Atanu Das - Men Archery 29 c) Jayanta Talukdar - Men Archery 30 d) Mangal Singh Champia - Men Archery 31 e) Viswash - Men Archery 32 f) Ranjit Naik - Men Archery 33 g) Sanjay Boro - Men Archery 34 h) Atul Verma - Men Archery 35 i) Binod Swansi - Men Archery 36 j) Deepika Kumari - Women Archery 37 k) L Bombayla Devi- Women Archery 38 l) Rimil Buriuly - Women Archery 39 m) Laxmi Rani Majhi - Women Archery 40 n) Dola Banerjee - Women Archery 41 o) Snehal Divakar- Women Archery 42 p) Madhu Vedwan - Women Archery Badminton 43 a) Saina Nehwal – Women’s singles 44 b) P.V. -

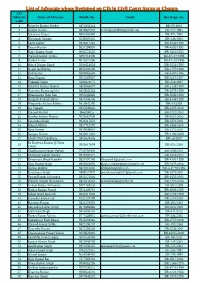

List of Advocate Whose Registred on CIS in Civil Court Saran at Chapra CIS Advocate Name of Advocate Mobile No

List of Advocate whose Registred on CIS in Civil Court Saran at Chapra CIS Advocate Name of Advocate Mobile No. Email Bar Regn. No. Code 1 Birendra Kumar Pandey 9470481114 BR-55/1992 2 Gunjan Verma 9934921847 [email protected] BR-733/1993 3 Mazharul Haque 9905403496 BR-883/1993 4 Bholanath Sharma 9546907435 BR-346/1994 5 Sunil Kumar 9835611348 BR-5740/1995 6 Pawan Kumar 9631594900 BR-4363/1995 7 Rajiv Kumar Singh 8002574542 BR-5310/1995 8 Pramod Kumar Verma 8651814306 BR-10127/1996 9 Pankaj Verma 9835075266 BR-10128/1996 10 Ashok Kumar Singh 9304014624 BR-2631/1996 11 Gopal Jee Pandey 9852088205 BR-2177/1996 12 Kishun Rai 9097962645 BR-8407/1996 13 Renu Kumari 9835268997 BR-3317/1997 14 Tripurari Singh 8292621173 BR-316/1997 15 Birendra Kumar Sharma 8409066877 BR-2124/1998 16 Narendra Kumar pandey 9430945334 BR-3879/1999 17 Dharmendra Nath Sah 9905266646 BR-6243/1999 18 Durgesh Prakash Bihari 9431406306 BR-4144/1999 19 Bhupendra Mohan Mishra 9430945395 BR-68/2009 20 Jay Prakash 9835649645 BR-2397/2010 21 Praveen Kumar 966194025 BR-3132/2003 22 Kundan Kumar Sharma 9525661909 BR-2023/2002 23 Satyendra Singh 9934217633 BR-2870/2001 24 Rakesh Milton 8507718379 BR-1861/2005 25 Ajay Kumar 9939849041 BR-1372/2001 26 Sanjeev Kumar 9430011002 BR-1196/2000 27 Shashi Nath Upadhyay 9430624506 BR-26/1999 Dr Rajeewa Kumar @ Pintu 28 9835617674 BR-951/2000 Tiwari 29 Shashiranjan Kumar Pathak 7739791080 BR-3590/2001 30 Mritunjay Kumar Pandey 9835843533 BR-3316/2003 31 Dineshwer SIngh Kaushik 9931807349 [email protected] BR-4761/1999 32 Ajay -

Androcentrism in Indian Sports

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Androcentrism in Indian sports Bijit Das [email protected] Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of Sociology Dibrugarh University Dibrugarh, Assam, India 786004 Abstract The personality of every individual concerning caste, creed, religion, gender in India depends on the structures of society. The society acts as a ladder in diffusing stereotypes from generation to generation which becomes a fundamental constructed ideal type for generalizing ideas on what is masculine or feminine. The gynocentric and androcentric division of labor in terms of work gives more potential for females in household works but not as the position of males. This paper is more concentrated on the biases of women in terms of sports and games which are male- dominated throughout the globe. The researcher looks at the growing stereotypes upon Indian sports as portrayed in various Indian cinemas. Content analysis is carried out on the movies Dangal and Chak de India to portray the prejudices shown by the Indian media. A total of five non-fictional sports movies are made in India in the name of Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013), Paan Singh Tomar(2012), MS Dhoni: An untold story(2016), Azhar(2016), Sachin: A billion dreams(26 May 2017) are on male sportsperson whereas only two movies are on women, namely Mary Kom (2014), Dangal(2017). This indicates that male preference is more than female in Indian media concerning any sports. The acquaintance of males in every sphere of life is being carried out from ancient to modern societies. This paper will widen the perspectives of not viewing society per media but to the independence and equity of both the sex in every sphere of life. -

IBPS RRB Capsule 2014

GK CAPSULE FOR IBPS RRBs 2014 EXAM This GK Capsule has been prepared by Career Power Institute Delhi (Formerly Known as Bank Power). This document consists of all important news and events of last few months which can come in SBI Clerk Exam. Current RBI Policy & Reserve Rates: Repo Rate 8% (Unchanged) Reverse Repo 7% (Unchanged) CRR 4% (Unchanged) SLR 22% (C hanged) MSF 9% (Unchanged) Bank Rate 9% (Unchanged) Note : As on 5 Aug 2014, RBI (Reserve Bank of India) in its Third bimonthly monetary policy statement kept the key policy rate (repo) unchanged. SLR was cut by 50 basis point from 22.5% to 22%. Important Banking Terminology: 1. Bank Rate: The interest rate at which at central bank lends money to commercial banks. Often these loans are very short in duration. Managing the bank rate is a preferred method by which central banks can regulate the level of economic activity. Lower bank rates can help to expand the economy, when unemployment is high, by lowering the cost of funds for borrowers. Conversely, higher bank rates help to reign in the economy, when inflation is higher than desired. 2. Liquidity adjustment facility (LAF) is a monetary policy tool which allows banks to borrow money through repurchase agreements. LAF is used to aid banks in adjusting the day to day mismatches in liquidity. LAF consists of repo and reverse repo operations. 3. Repo Rate: Whenever the banks have any shortage of funds they can borrow it form RBI. Repo rate is the rate at which commercial banks borrows rupees from RBI. -

Important Questions on General Awareness Part 1 for Competitive Exam

Important Questions on General Awareness Part 1 for Competitive Exam. 1. Who grabbed India's first athletics medal in the 20th edition of Common wealth Games ? Ans- Vikas Gowda 2. Book “One Life is Not Enough: An Autobiography” written by.. Ans- Kunwar Natwar Singh 3. Which player has been suspended from Indian men hockey team in the Commonwealth Games 2014 ? Ans- Sardar Singh 4. Which country will sign a pact with India for new BrahMos missile version Su-30MKI. Ans- Russia 5. Double-Decker train will run between the..............and …….. Ans- Lucknow & New Delhi 6. Which Indian women wrestler bagged gold medal in 55kg freestyle in Commonwealth Games 2014 Ans- Babita Kumari 7. RBI has recently cancelled the licence of................in Hyderabad (Telangana). Ans- Vasai Co-operative Urban Bank Ltd 8. Name the US Defence Secretary who visited New Delhi to encourage defence ties between the duos. Ans- Alfredo Di Stefano 9. National Security Advisor in defence ? Ans- Ajit K Doval 10. The first Indian woman mountaineer...................... has been awarded with …………… Ans- Bachendri Pal , Bharat Gaurav 11. Who is the first Indian woman gymnast who won bronze medal in Commonwealth Games 2014 ? Ans- Dipa Karmakar 12. India and Nepal has recently signed pacts which include 5,600 MW. Name of the project is …… Ans- Pancheshwar Multipurpose Project 13. Who received Ramon Magsaysay Awards 2014 ? Ans- Hu Shuli and Wang Canfa 14. Which edition of Commonwealth Games (CWG) 2014 was held recently ? Ans- 20 15. Which country topped with the most medals in Commonwealth Games 2014 ? Ans- Scotland 16. Which Indian men wrestler bagged gold in 65kg freestyle in Commonwealth Games 2014. -

Athletics, Badminton, Gymnastics, Judo, Swimming, Table Tennis, and Wrestling

INDIVIDUAL GAMES 4 Games and sports are important parts of our lives. They are essential to enjoy overall health and well-being. Sports and games offer numerous advantages and are thus highly recommended for everyone irrespective of their age. Sports with individualistic approach characterised with graceful skills of players are individual sports. Do you like the idea of playing an individual sport and be responsible for your win or loss, success or failure? There are various sports that come under this category. This chapter will help you to enhance your knowledge about Athletics, Badminton, Gymnastics, Judo, Swimming, Table Tennis, and Wrestling. ATHLETICS Running, jumping and throwing are natural and universal forms of human physical expression. Track and field events are the improved versions of all these. These are among the oldest of all sporting competitions. Athletics consist of track and field events. In the track events, competitions of races of different distances are conducted. The different track and field events have their roots in ancient human history. History Ancient Olympic Games are the first recorded examples of organised track and field events. In 776 B.C., in Olympia, Greece, only one event was contested which was known as the stadion footrace. The scope of the games expanded in later years. Further it included running competitions, but the introduction of the Ancient Olympic pentathlon marked a step towards track and field as it is recognised today. There were five events in pentathlon namely—discus throw, long jump, javelin throw, the stadion foot race, and wrestling. 2021-22 Chap-4.indd 49 31-07-2020 15:26:11 50 Health and Physical Education - XI Track and field events were also present at the Pan- Activity 4.1 Athletics at the 1960 Summer Hellenic Games in Greece around 200 B.C.