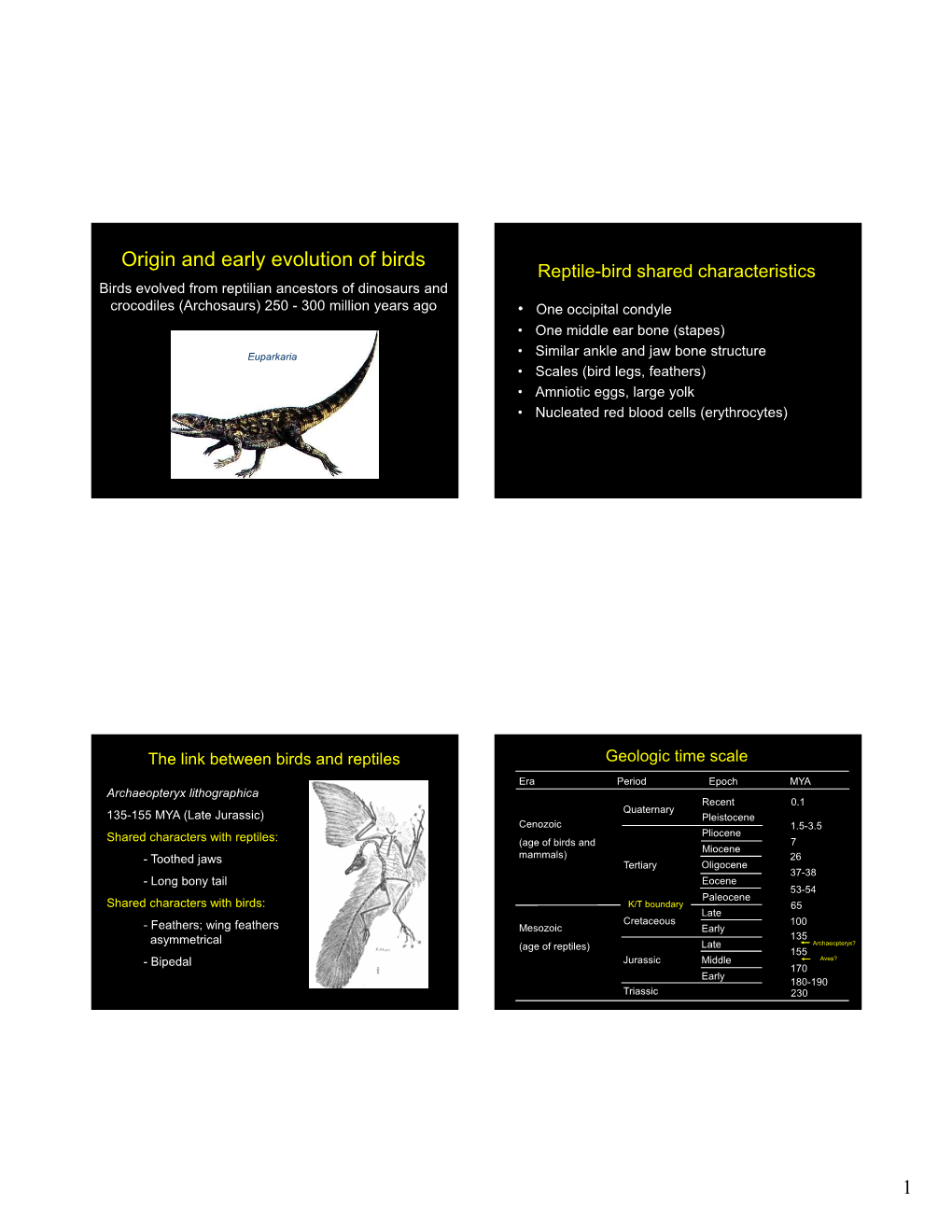

1 Origin and Early Evolution of Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anchiornis and Scansoriopterygidae

SpringerBriefs in Earth System Sciences SpringerBriefs South America and the Southern Hemisphere Series Editors Gerrit Lohmann Lawrence A. Mysak Justus Notholt Jorge Rabassa Vikram Unnithan For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/10032 Federico L. Agnolín · Fernando E. Novas Avian Ancestors A Review of the Phylogenetic Relationships of the Theropods Unenlagiidae, Microraptoria, Anchiornis and Scansoriopterygidae 1 3 Federico L. Agnolín “Félix de Azara”, Departamento de Ciencias Naturales Fundación de Historia Natural, CEBBAD, Universidad Maimónides Buenos Aires Argentina Fernando E. Novas CONICET, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia” Buenos Aires Argentina ISSN 2191-589X ISSN 2191-5903 (electronic) ISBN 978-94-007-5636-6 ISBN 978-94-007-5637-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-5637-3 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg New York London Library of Congress Control Number: 2012953463 © The Author(s) 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. -

A Chinese Archaeopterygian, Protarchaeopteryx Gen. Nov

A Chinese archaeopterygian, Protarchaeopteryx gen. nov. by Qiang Ji and Shu’an Ji Geological Science and Technology (Di Zhi Ke Ji) Volume 238 1997 pp. 38-41 Translated By Will Downs Bilby Research Center Northern Arizona University January, 2001 Introduction* The discoveries of Confuciusornis (Hou and Zhou, 1995; Hou et al, 1995) and Sinornis (Ji and Ji, 1996) have profoundly stimulated ornithologists’ interest globally in the Beipiao region of western Liaoning Province. They have also regenerated optimism toward solving questions of avian origins. In December 1996, the Chinese Geological Museum collected a primitive bird specimen at Beipiao that is comparable to Archaeopteryx (Wellnhofer, 1992). The specimen was excavated from a marl 5.5 m above the sediments that produce Sinornithosaurus and 8-9 m below the sediments that produce Confuciusornis. This is the first documentation of an archaeopterygian outside Germany. As a result, this discovery not only establishes western Liaoning Province as a center of avian origins and evolution, it provides conclusive evidence for the theory that avian evolution occurred in four phases. Specimen description Class Aves Linnaeus, 1758 Subclass Sauriurae Haeckel, 1866 Order Archaeopterygiformes Furbringer, 1888 Family Archaeopterygidae Huxley, 1872 Genus Protarchaeopteryx gen. nov. Genus etymology: Acknowledges that the specimen possesses characters more primitive than those of Archaeopteryx. Diagnosis: A primitive archaeopterygian with claviform and unserrated dentition. Sternum is thin and flat, tail is long, and forelimb resembles Archaeopteryx in morphology with three talons, the second of which is enlarged. Ilium is large and elongated, pubes are robust and distally fused, hind limb is long and robust with digit I reduced and dorsally migrated to lie in opposition to digit III and forming a grasping apparatus. -

LETTER Doi:10.1038/Nature14423

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature14423 A bizarre Jurassic maniraptoran theropod with preserved evidence of membranous wings Xing Xu1,2*, Xiaoting Zheng1,3*, Corwin Sullivan2, Xiaoli Wang1, Lida Xing4, Yan Wang1, Xiaomei Zhang3, Jingmai K. O’Connor2, Fucheng Zhang2 & Yanhong Pan5 The wings of birds and their closest theropod relatives share a ratios are 1.16 and 1.08, respectively, compared to 0.96 and 0.78 in uniform fundamental architecture, with pinnate flight feathers Epidendrosaurus and 0.79 and 0.66 in Epidexipteryx), an extremely as the key component1–3. Here we report a new scansoriopterygid short humeral deltopectoral crest, and a long rod-like bone articu- theropod, Yi qi gen. et sp. nov., based on a new specimen from the lating with the wrist. Middle–Upper Jurassic period Tiaojishan Formation of Hebei Key osteological features are as follows. STM 31-2 (Fig. 1) is inferred Province, China4. Yi is nested phylogenetically among winged ther- to be an adult on the basis of the closed neurocentral sutures of the opods but has large stiff filamentous feathers of an unusual type on visible vertebrae, although this is not a universal criterion for maturity both the forelimb and hindlimb. However, the filamentous feath- across archosaurian taxa12. Its body mass is estimated to be approxi- ers of Yi resemble pinnate feathers in bearing morphologically mately 380 g, using an empirical equation13. diverse melanosomes5. Most surprisingly, Yi has a long rod-like The skull and mandible are similar to those of other scansoriopter- bone extending from each wrist, and patches of membranous tissue ygids, and to a lesser degree to those of oviraptorosaurs and some basal preserved between the rod-like bones and the manual digits. -

A New Raptorial Dinosaur with Exceptionally Long Feathering Provides Insights Into Dromaeosaurid flight Performance

ARTICLE Received 11 Apr 2014 | Accepted 11 Jun 2014 | Published 15 Jul 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5382 A new raptorial dinosaur with exceptionally long feathering provides insights into dromaeosaurid flight performance Gang Han1, Luis M. Chiappe2, Shu-An Ji1,3, Michael Habib4, Alan H. Turner5, Anusuya Chinsamy6, Xueling Liu1 & Lizhuo Han1 Microraptorines are a group of predatory dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaurs with aero- dynamic capacity. These close relatives of birds are essential for testing hypotheses explaining the origin and early evolution of avian flight. Here we describe a new ‘four-winged’ microraptorine, Changyuraptor yangi, from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota of China. With tail feathers that are nearly 30 cm long, roughly 30% the length of the skeleton, the new fossil possesses the longest known feathers for any non-avian dinosaur. Furthermore, it is the largest theropod with long, pennaceous feathers attached to the lower hind limbs (that is, ‘hindwings’). The lengthy feathered tail of the new fossil provides insight into the flight performance of microraptorines and how they may have maintained aerial competency at larger body sizes. We demonstrate how the low-aspect-ratio tail of the new fossil would have acted as a pitch control structure reducing descent speed and thus playing a key role in landing. 1 Paleontological Center, Bohai University, 19 Keji Road, New Shongshan District, Jinzhou, Liaoning Province 121013, China. 2 Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007, USA. 3 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, 26 Baiwanzhuang Road, Beijing 100037, China. 4 University of Southern California, Health Sciences Campus, BMT 403, Mail Code 9112, Los Angeles, California 90089, USA. -

Perinate and Eggs of a Giant Caenagnathid Dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Central China

ARTICLE Received 29 Jul 2016 | Accepted 15 Feb 2017 | Published 9 May 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms14952 OPEN Perinate and eggs of a giant caenagnathid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of central China Hanyong Pu1, Darla K. Zelenitsky2, Junchang Lu¨3, Philip J. Currie4, Kenneth Carpenter5,LiXu1, Eva B. Koppelhus4, Songhai Jia1, Le Xiao1, Huali Chuang1, Tianran Li1, Martin Kundra´t6 & Caizhi Shen3 The abundance of dinosaur eggs in Upper Cretaceous strata of Henan Province, China led to the collection and export of countless such fossils. One of these specimens, recently repatriated to China, is a partial clutch of large dinosaur eggs (Macroelongatoolithus) with a closely associated small theropod skeleton. Here we identify the specimen as an embryo and eggs of a new, large caenagnathid oviraptorosaur, Beibeilong sinensis. This specimen is the first known association between skeletal remains and eggs of caenagnathids. Caenagnathids and oviraptorids share similarities in their eggs and clutches, although the eggs of Beibeilong are significantly larger than those of oviraptorids and indicate an adult body size comparable to a gigantic caenagnathid. An abundance of Macroelongatoolithus eggs reported from Asia and North America contrasts with the dearth of giant caenagnathid skeletal remains. Regardless, the large caenagnathid-Macroelongatoolithus association revealed here suggests these dinosaurs were relatively common during the early Late Cretaceous. 1 Henan Geological Museum, Zhengzhou 450016, China. 2 Department of Geoscience, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 1N4. 3 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100037, China. 4 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E9. 5 Prehistoric Museum, Utah State University, 155 East Main Street, Price, Utah 84501, USA. -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

A New Caenagnathid Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Wangshi

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A new caenagnathid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Wangshi Group of Shandong, China, with Received: 12 October 2017 Accepted: 7 March 2018 comments on size variation among Published: xx xx xxxx oviraptorosaurs Yilun Yu1, Kebai Wang2, Shuqing Chen2, Corwin Sullivan3,4, Shuo Wang 5,6, Peiye Wang2 & Xing Xu7 The bone-beds of the Upper Cretaceous Wangshi Group in Zhucheng, Shandong, China are rich in fossil remains of the gigantic hadrosaurid Shantungosaurus. Here we report a new oviraptorosaur, Anomalipes zhaoi gen. et sp. nov., based on a recently collected specimen comprising a partial left hindlimb from the Kugou Locality in Zhucheng. This specimen’s systematic position was assessed by three numerical cladistic analyses based on recently published theropod phylogenetic datasets, with the inclusion of several new characters. Anomalipes zhaoi difers from other known caenagnathids in having a unique combination of features: femoral head anteroposteriorly narrow and with signifcant posterior orientation; accessory trochanter low and confuent with lesser trochanter; lateral ridge present on femoral lateral surface; weak fourth trochanter present; metatarsal III with triangular proximal articular surface, prominent anterior fange near proximal end, highly asymmetrical hemicondyles, and longitudinal groove on distal articular surface; and ungual of pedal digit II with lateral collateral groove deeper and more dorsally located than medial groove. The holotype of Anomalipes zhaoi is smaller than is typical for Caenagnathidae but larger than is typical for the other major oviraptorosaurian subclade, Oviraptoridae. Size comparisons among oviraptorisaurians show that the Caenagnathidae vary much more widely in size than the Oviraptoridae. Oviraptorosauria is a clade of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs characterized by a short, high skull, long neck and short tail. -

The Mesozoic Era Alvarez, W.(1997)

Alles Introductory Biology: Illustrated Lecture Presentations Instructor David L. Alles Western Washington University ----------------------- Part Three: The Integration of Biological Knowledge Vertebrate Evolution in the Late Paleozoic and Mesozoic Eras ----------------------- Vertebrate Evolution in the Late Paleozoic and Mesozoic • Amphibians to Reptiles Internal Fertilization, the Amniotic Egg, and a Water-Tight Skin • The Adaptive Radiation of Reptiles from Scales to Hair and Feathers • Therapsids to Mammals • Dinosaurs to Birds Ectothermy to Endothermy The Evolution of Reptiles The Phanerozoic Eon 444 365 251 Paleozoic Era 542 m.y.a. 488 416 360 299 Camb. Ordov. Sil. Devo. Carbon. Perm. Cambrian Pikaia Fish Fish First First Explosion w/o jaws w/ jaws Amphibians Reptiles 210 65 Mesozoic Era 251 200 180 150 145 Triassic Jurassic Cretaceous First First First T. rex Dinosaurs Mammals Birds Cenozoic Era Last Ice Age 65 56 34 23 5 1.8 0.01 Paleo. Eocene Oligo. Miocene Plio. Ple. Present Early Primate First New First First Modern Cantius World Monkeys Apes Hominins Humans A modern Amphibian—the toad A modern day Reptile—a skink, note the finely outlined scales. A Comparison of Amphibian and Reptile Reproduction The oldest known reptile is Hylonomus lyelli dating to ~ 320 m.y.a.. The earliest or stem reptiles radiated into therapsids leading to mammals, and archosaurs leading to all the other reptile groups including the thecodontians, ancestors of the dinosaurs. Dimetrodon, a Mammal-like Reptile of the Early Permian Dicynodonts were a group of therapsids of the late Permian. Web Reference http://www.museums.org.za/sam/resource/palaeo/cluver/index.html Therapsids experienced an adaptive radiation during the Permian, but suffered heavy extinctions during the end Permian mass extinction. -

The Dazzling Diversity of Avian Feet I I Text Lisa Nupen Anisodactyl

BIOLOGY insight into the birds’ different modes of life. THE BONES IN THE TOES Birds’ feet are not only used for n almost all birds, the number of bones locomotion (walking or running, Iin each toe is preserved: there are two swimming, climbing), but they bones in the first toe (digit I), three bones serve other important functions in in the second toe (II), four in the third (III) perching, foraging, preening, re- and five in the fourth (IV). Therefore, the production and thermoregulation. identity of a toe (I to IV) can be determined Because of this, the structure of a quite reliably from the number of bones in bird’s foot often provides insight it. When evolutionary toe-loss occurs, this into the species’ ecology. Often, makes it possible to identify which digit distantly related species have con- has been lost. verged on similar foot types when adapting to particular environ- ments. For example, the four fully demands of a particular niche or The first, and seemingly ances- webbed, forward-pointing toes environment. The arrangement tral, configuration of birds’ toes – called totipalmate – of pelicans, of toes in lovebirds, barbets and – called anisodactyly – has three gannets and cormorants are an ad- cuckoos, for example, is differ- digits (numbered II, III and IV) aptation to their marine habitat. ent from that in passerines (such orientated forwards and digit I The closely related Shoebill as finches, shrikes or starlings) in (the ‘big toe’, or hallux) pointing does not have webbed feet, per- the same environment. The func- backwards. This arrangement is haps because of its wetland habi- tional reasons for differences in shared with theropod fossils and The toes of penguins tat, but the tropicbirds, which foot structure can be difficult to is the most common, being found (below left) and gan- fancy form their own relatively ancient explain. -

Mousebirds Tle Focus Has Been Placed Upon Them

at all, in private aviculture, and only a few zoos have them in their col1ec tions. According to the ISIS report of September 1998, Red-hacks are not to be found in any USA collections. This is unfortunate as all six species have been imported in the past although lit Mousebirds tle focus has been placed upon them. Hopeful1y this will change in the for the New Millennium upcoming years. Speckled Mousebirds by Kateri J. Davis, Sacramento, CA Speckled Mousebirds Colius striatus, also known as Bar-breasted or Striated, are the most common mousebirds in crops and frequent village gardens. USA private and zoological aviculture he word is slowly spreading; They are considered a pest bird by today. There are 17 subspecies, differ mousebirds make great many Africans and destroyed as such. ing mainly in color of the legs, eyes, T aviary birds and, surprising Luckily, so far none of the mousebird throat, and cheek patches or ear ly, great household pets. Although still species are endangered or listed on coverts. They have reddish brown body generally unknown, they are the up CITES even though some of them have plumage with dark barrings and a very and-coming pet bird of the new mil naturally small ranges. wide, long, stiff tail. Their feathering is lennium. They share many ofthe qual Mousebirds are not closely related to soft and easily damaged. They have a ities ofsmall pet parrots, but lack many any other bird species, although they soft chattering cal1 and are the most of their vices, which helps explain share traits with parrots. -

Leptosomiformes ~ Trogoniformes ~ Bucerotiformes ~ Piciformes

Birds of the World part 6 Afroaves The core landbirds originating in Africa TELLURAVES: AFROAVES – core landbirds originating in Africa (8 orders) • ORDER ACCIPITRIFORMES – hawks and allies (4 families, 265 species) – Family Cathartidae – New World vultures (7 species) – Family Sagittariidae – secretarybird (1 species) – Family Pandionidae – ospreys (2 species) – Family Accipitridae – kites, hawks, and eagles (255 species) • ORDER STRIGIFORMES – owls (2 families, 241 species) – Family Tytonidae – barn owls (19 species) – Family Strigidae – owls (222 species) • ORDER COLIIFORMES (1 family, 6 species) – Family Coliidae – mousebirds (6 species) • ORDER LEPTOSOMIFORMES (1 family, 1 species) – Family Leptosomidae – cuckoo-roller (1 species) • ORDER TROGONIFORMES (1 family, 43 species) – Family Trogonidae – trogons (43 species) • ORDER BUCEROTIFORMES – hornbills and hoopoes (4 families, 74 species) – Family Upupidae – hoopoes (4 species) – Family Phoeniculidae – wood hoopoes (9 species) – Family Bucorvidae – ground hornbills (2 species) – Family Bucerotidae – hornbills (59 species) • ORDER PICIFORMES – woodpeckers and allies (9 families, 443 species) – Family Galbulidae – jacamars (18 species) – Family Bucconidae – puffbirds (37 species) – Family Capitonidae – New World barbets (15 species) – Family Semnornithidae – toucan barbets (2 species) – Family Ramphastidae – toucans (46 species) – Family Megalaimidae – Asian barbets (32 species) – Family Lybiidae – African barbets (42 species) – Family Indicatoridae – honeyguides (17 species) – Family -

ORIGIN and EVOLUTION of BIRDS Dr. Ramesh Pathak B.Sc. (Hons.) –II

ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF BIRDS Dr. Ramesh Pathak B.Sc. (hons.) –II Prof. Parker has shown a number of peculiarities between birds and repiles,so,he said “birds are transformed and glorified reptiles”. Huxley has established a very close relationship by saying birds are “feathered reptiles”. THEORIES OF ORIGIN OF BIRDS A. Cursorial theory : This theory was championed by Baron Nopsa who maintained that the birds evolved from cursorial bipedal dinosaurs. In attempt to move faster during running to pull themselves a bit faster they moved and beat their arms. In such condition, due to continuous use of arms as propellers brought constant increase in the length and breadth of scales present on them. As the scales lengthened ,the pressure against the air caused their edges frayed leading to scales changing into feathers. But this theory was rejected because scales and feathers are fundamentally different structures arising from different layers of skin. B.Tetrapteryx theory :It was proposed by Beebe and Gregorg. According to this theory the ancestors of birds were arboreal reptiles who used to jump from branch to branch and in doing so the scales were transformed into feathers by fraying of the edges. After developing feathers on all the four limbs (Tetrapteryx stage), they used only the anterior wings and the unused posterior wings were lost. This theory was also discarded because there is no evidence that birds had ever four wings. C. Gliding thery : It is based on the idea of Beebe and Georg.It was proposed by Heilmann but does not recognize the tetrapteryx stage.