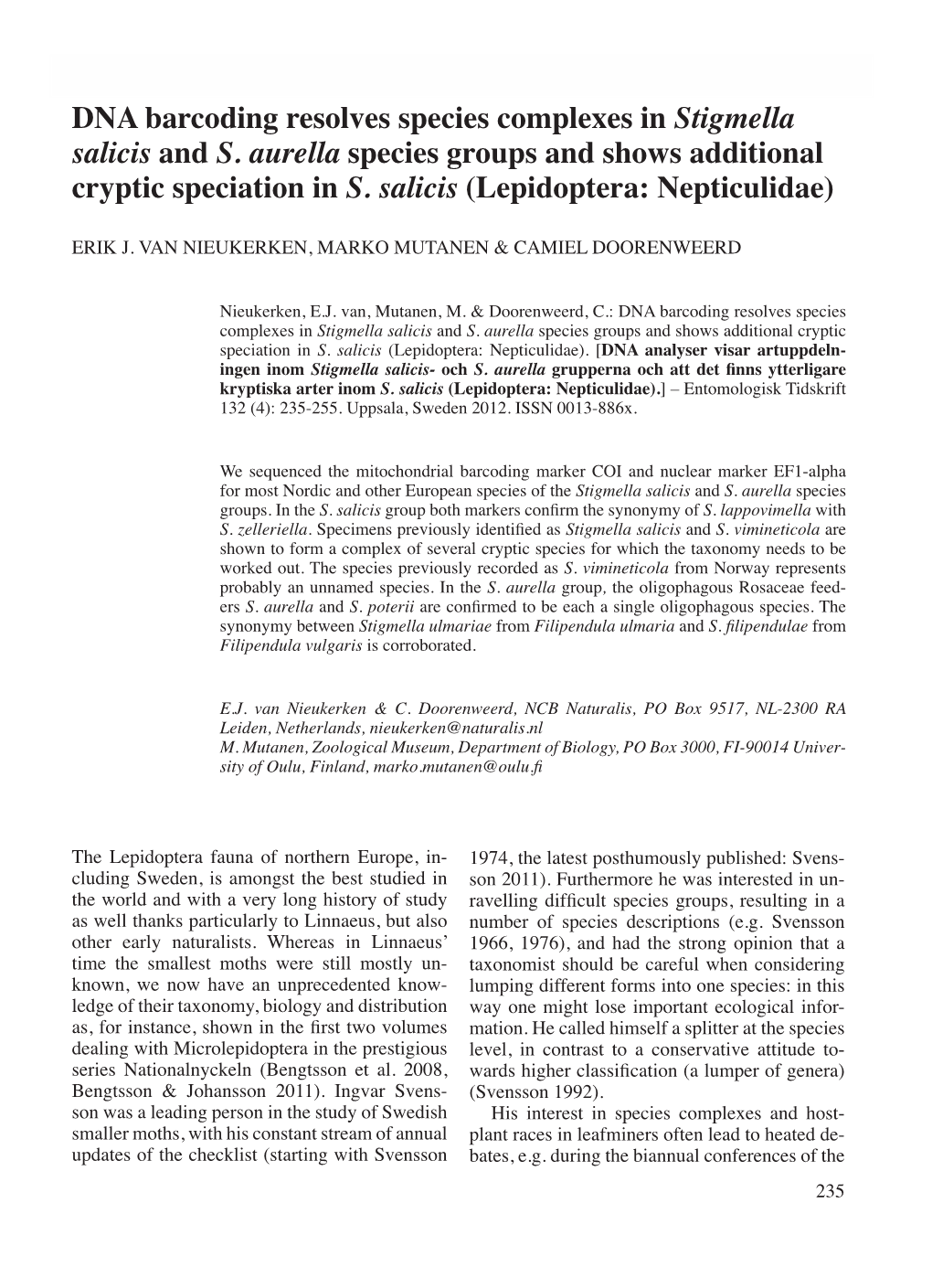

DNA Barcoding Resolves Species Complexes in Stigmella Salicis and S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYSTEMATICS of the MEGADIVERSE SUPERFAMILY GELECHIOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTEA) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of T

SYSTEMATICS OF THE MEGADIVERSE SUPERFAMILY GELECHIOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTEA) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sibyl Rae Bucheli, M.S. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. John W. Wenzel, Advisor Dr. Daniel Herms Dr. Hans Klompen _________________________________ Dr. Steven C. Passoa Advisor Graduate Program in Entomology ABSTRACT The phylogenetics, systematics, taxonomy, and biology of Gelechioidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) are investigated. This superfamily is probably the second largest in all of Lepidoptera, and it remains one of the least well known. Taxonomy of Gelechioidea has been unstable historically, and definitions vary at the family and subfamily levels. In Chapters Two and Three, I review the taxonomy of Gelechioidea and characters that have been important, with attention to what characters or terms were used by different authors. I revise the coding of characters that are already in the literature, and provide new data as well. Chapter Four provides the first phylogenetic analysis of Gelechioidea to include molecular data. I combine novel DNA sequence data from Cytochrome oxidase I and II with morphological matrices for exemplar species. The results challenge current concepts of Gelechioidea, suggesting that traditional morphological characters that have united taxa may not be homologous structures and are in need of further investigation. Resolution of this problem will require more detailed analysis and more thorough characterization of certain lineages. To begin this task, I conduct in Chapter Five an in- depth study of morphological evolution, host-plant selection, and geographical distribution of a medium-sized genus Depressaria Haworth (Depressariinae), larvae of ii which generally feed on plants in the families Asteraceae and Apiaceae. -

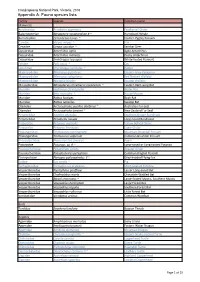

Micro-Moth Grading Guidelines (Scotland) Abhnumber Code

Micro-moth Grading Guidelines (Scotland) Scottish Adult Mine Case ABHNumber Code Species Vernacular List Grade Grade Grade Comment 1.001 1 Micropterix tunbergella 1 1.002 2 Micropterix mansuetella Yes 1 1.003 3 Micropterix aureatella Yes 1 1.004 4 Micropterix aruncella Yes 2 1.005 5 Micropterix calthella Yes 2 2.001 6 Dyseriocrania subpurpurella Yes 2 A Confusion with fly mines 2.002 7 Paracrania chrysolepidella 3 A 2.003 8 Eriocrania unimaculella Yes 2 R Easier if larva present 2.004 9 Eriocrania sparrmannella Yes 2 A 2.005 10 Eriocrania salopiella Yes 2 R Easier if larva present 2.006 11 Eriocrania cicatricella Yes 4 R Easier if larva present 2.007 13 Eriocrania semipurpurella Yes 4 R Easier if larva present 2.008 12 Eriocrania sangii Yes 4 R Easier if larva present 4.001 118 Enteucha acetosae 0 A 4.002 116 Stigmella lapponica 0 L 4.003 117 Stigmella confusella 0 L 4.004 90 Stigmella tiliae 0 A 4.005 110 Stigmella betulicola 0 L 4.006 113 Stigmella sakhalinella 0 L 4.007 112 Stigmella luteella 0 L 4.008 114 Stigmella glutinosae 0 L Examination of larva essential 4.009 115 Stigmella alnetella 0 L Examination of larva essential 4.010 111 Stigmella microtheriella Yes 0 L 4.011 109 Stigmella prunetorum 0 L 4.012 102 Stigmella aceris 0 A 4.013 97 Stigmella malella Apple Pigmy 0 L 4.014 98 Stigmella catharticella 0 A 4.015 92 Stigmella anomalella Rose Leaf Miner 0 L 4.016 94 Stigmella spinosissimae 0 R 4.017 93 Stigmella centifoliella 0 R 4.018 80 Stigmella ulmivora 0 L Exit-hole must be shown or larval colour 4.019 95 Stigmella viscerella -

Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) 321-356 ©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Entomofauna Jahr/Year: 2007 Band/Volume: 0028 Autor(en)/Author(s): Yefremova Zoya A., Ebrahimi Ebrahim, Yegorenkova Ekaterina Artikel/Article: The Subfamilies Eulophinae, Entedoninae and Tetrastichinae in Iran, with description of new species (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) 321-356 ©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Entomofauna ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR ENTOMOLOGIE Band 28, Heft 25: 321-356 ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 30. November 2007 The Subfamilies Eulophinae, Entedoninae and Tetrastichinae in Iran, with description of new species (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) Zoya YEFREMOVA, Ebrahim EBRAHIMI & Ekaterina YEGORENKOVA Abstract This paper reflects the current degree of research of Eulophidae and their hosts in Iran. A list of the species from Iran belonging to the subfamilies Eulophinae, Entedoninae and Tetrastichinae is presented. In the present work 47 species from 22 genera are recorded from Iran. Two species (Cirrospilus scapus sp. nov. and Aprostocetus persicus sp. nov.) are described as new. A list of 45 host-parasitoid associations in Iran and keys to Iranian species of three genera (Cirrospilus, Diglyphus and Aprostocetus) are included. Zusammenfassung Dieser Artikel zeigt den derzeitigen Untersuchungsstand an eulophiden Wespen und ihrer Wirte im Iran. Eine Liste der für den Iran festgestellten Arten der Unterfamilien Eu- lophinae, Entedoninae und Tetrastichinae wird präsentiert. Mit vorliegender Arbeit werden 47 Arten in 22 Gattungen aus dem Iran nachgewiesen. Zwei neue Arten (Cirrospilus sca- pus sp. nov. und Aprostocetus persicus sp. nov.) werden beschrieben. Eine Liste von 45 Wirts- und Parasitoid-Beziehungen im Iran und ein Schlüssel für 3 Gattungen (Cirro- spilus, Diglyphus und Aprostocetus) sind in der Arbeit enthalten. -

Report-VIC-Croajingolong National Park-Appendix A

Croajingolong National Park, Victoria, 2016 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Mammals Acrobatidae Acrobates pygmaeus Feathertail Glider Balaenopteriae Megaptera novaeangliae # ~ Humpback Whale Burramyidae Cercartetus nanus ~ Eastern Pygmy Possum Canidae Vulpes vulpes ^ Fox Cervidae Cervus unicolor ^ Sambar Deer Dasyuridae Antechinus agilis Agile Antechinus Dasyuridae Antechinus mimetes Dusky Antechinus Dasyuridae Sminthopsis leucopus White-footed Dunnart Felidae Felis catus ^ Cat Leporidae Oryctolagus cuniculus ^ Rabbit Macropodidae Macropus giganteus Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropodidae Macropus rufogriseus Red Necked Wallaby Macropodidae Wallabia bicolor Swamp Wallaby Miniopteridae Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis ~ Eastern Bent-wing Bat Muridae Hydromys chrysogaster Water Rat Muridae Mus musculus ^ House Mouse Muridae Rattus fuscipes Bush Rat Muridae Rattus lutreolus Swamp Rat Otariidae Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus ~ Australian Fur-seal Otariidae Arctocephalus forsteri ~ New Zealand Fur Seal Peramelidae Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot Peramelidae Perameles nasuta Long-nosed Bandicoot Petauridae Petaurus australis Yellow Bellied Glider Petauridae Petaurus breviceps Sugar Glider Phalangeridae Trichosurus cunninghami Mountain Brushtail Possum Phalangeridae Trichosurus vulpecula Common Brushtail Possum Phascolarctidae Phascolarctos cinereus Koala Potoroidae Potorous sp. # ~ Long-nosed or Long-footed Potoroo Pseudocheiridae Petauroides volans Greater Glider Pseudocheiridae Pseudocheirus peregrinus -

Moths of Poole Harbour Species List

Moths of Poole Harbour is a project of Birds of Poole Harbour Moths of Poole Harbour Species List Birds of Poole Harbour & Moths of Poole Harbour recording area The Moths of Poole Harbour Project The ‘Moths of Poole Harbour’ project (MoPH) was established in 2017 to gain knowledge of moth species occurring in Poole Harbour, Dorset, their distribution, abundance and to some extent, their habitat requirements. The study area uses the same boundaries as the Birds of Poole Harbour (BoPH) project. Abigail Gibbs and Chris Thain, previous Wardens on Brownsea Island for Dorset Wildlife Trust (DWT), were invited by BoPH to undertake a study of moths in the Poole Harbour recording area. This is an area of some 175 square kilometres stretching from Corfe Castle in the south to Canford Heath in the north of the conurbation and west as far as Wareham. 4 moth traps were purchased for the project; 3 Mercury Vapour (MV) Robinson traps with 50m extension cables and one Actinic, Ultra-violet (UV) portable Heath trap running from a rechargeable battery. This was the capability that was deployed on most of the ensuing 327 nights of trapping. Locations were selected using a number of criteria: Habitat, accessibility, existing knowledge (previously well-recorded sites were generally not included), potential for repeat visits, site security and potential for public engagement. Field work commenced from late July 2017 and continued until October. Generally, in the years 2018 – 2020 trapping field work began in March/ April and ran on until late October or early November, stopping at the first frost. -

Leafminers Nunn & Warrington

More dots on the map: further records of leafmining moths in East Yorkshire Andy D. Nunn1 and Barry Warrington2 1Hull International Fisheries Institute, School of Biological, Biomedical & Environmental Sciences, University of Hull, Hull, HU6 7RX, UK. Email: [email protected] 236 Marlborough Avenue, Hessle, HU13 0PN, UK. Email: [email protected] The apparent scarcity of many leafmining moths in East Yorkshire (see Sutton & Beaumont, 1989) is at least partly due to a lack of recorder effort, and a number of previously presumed scarce or rare moths are actually relatively widespread (Chesmore, 2008; Nunn, 2015). One of the aims of a previous article (Nunn, op. cit.) was, hopefully, to encourage searches for leafminers in an attempt to redress the imbalance of records in Yorkshire. This article summarises our 'leafminering' highlights from 2015. A number of sites in VC61 were searched for leafmining moths (Table 1). Sampling effort varied considerably between sites. AN’s ‘leafminering’ opportunities were mostly restricted to casual observations while on family outings; BW’s focussed on sites that could be reached using public transport. The most time was spent in the Hessle area and a productive site in Hull. In October, the authors joined Charlie Fletcher and Ian Marshall for a day in an under- recorded 10km square, concentrating on the Settrington area. North Cliffe Wood was visited only in late spring and early summer, and other sites were visited briefly in the autumn. Table 1. Most notable records by the authors of leafmining moths -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to An

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) WITH A CONCISE CHECKLIST OF IRISH SPECIES AND ELACHISTA BIATOMELLA (STAINTON, 1848) NEW TO IRELAND K. G. M. Bond1 and J. P. O’Connor2 1Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, School of BEES, University College Cork, Distillery Fields, North Mall, Cork, Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 2Emeritus Entomologist, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. Abstract Additions, deletions and corrections are made to the Irish checklist of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera). Elachista biatomella (Stainton, 1848) is added to the Irish list. The total number of confirmed Irish species of Lepidoptera now stands at 1480. Key words: Lepidoptera, additions, deletions, corrections, Irish list, Elachista biatomella Introduction Bond, Nash and O’Connor (2006) provided a checklist of the Irish Lepidoptera. Since its publication, many new discoveries have been made and are reported here. In addition, several deletions have been made. A concise and updated checklist is provided. The following abbreviations are used in the text: BM(NH) – The Natural History Museum, London; NMINH – National Museum of Ireland, Natural History, Dublin. The total number of confirmed Irish species now stands at 1480, an addition of 68 since Bond et al. (2006). Taxonomic arrangement As a result of recent systematic research, it has been necessary to replace the arrangement familiar to British and Irish Lepidopterists by the Fauna Europaea [FE] system used by Karsholt 60 Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) and Razowski, which is widely used in continental Europe. -

Salix L.) in the European Alps

diversity Review The Evolutionary History, Diversity, and Ecology of Willows (Salix L.) in the European Alps Natascha D. Wagner 1 , Li He 2 and Elvira Hörandl 1,* 1 Department of Systematics, Biodiversity and Evolution of Plants (with Herbarium), University of Goettingen, Untere Karspüle 2, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; [email protected] 2 College of Forestry, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou 350002, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The genus Salix (willows), with 33 species, represents the most diverse genus of woody plants in the European Alps. Many species dominate subalpine and alpine types of vegetation. Despite a long history of research on willows, the evolutionary and ecological factors for this species richness are poorly known. Here we will review recent progress in research on phylogenetic relation- ships, evolution, ecology, and speciation in alpine willows. Phylogenomic reconstructions suggest multiple colonization of the Alps, probably from the late Miocene onward, and reject hypotheses of a single radiation. Relatives occur in the Arctic and in temperate Eurasia. Most species are widespread in the European mountain systems or in the European lowlands. Within the Alps, species differ eco- logically according to different elevational zones and habitat preferences. Homoploid hybridization is a frequent process in willows and happens mostly after climatic fluctuations and secondary contact. Breakdown of the ecological crossing barriers of species is followed by introgressive hybridization. Polyploidy is an important speciation mechanism, as 40% of species are polyploid, including the four endemic species of the Alps. Phylogenomic data suggest an allopolyploid origin for all taxa analyzed Citation: Wagner, N.D.; He, L.; so far. -

1.Jūras Un Iesāļu Augteņu Biotopi

1. Jūras un iesāļu augteņu biotopi Iepriekšējais nosaukums: Piekrastes un halofītiskie biotopi ārējā robeža – tāpēc Latvijā ir saglabājušās daļēji mazskartas (iepriekšējais nosaukums neprecīzi atspoguļoja biotopu un vietām neskartas pludmales, jūras seklūdens un piejūras grupas būtību). platības. Jūras un iesāļu augteņu biotopu grupā ir apvienoti gan jūras biotopi, gan biotopi, kas saistīti ar jūras ietekmi: pludmales Aizsardzības vērtība un citi ar iesāļu jūras ūdeni sezonāli vai neregulāri applūstoši Lai arī šai biotopu grupai Latvijā ir potenciāli ļoti labas izplatības biotopi Piejūras zemienē. Daudzveidīgajā biotopu grupā un attīstības iespējas, tā kopumā ir pieskaitāma ļoti retiem un apvienoti gan īslaicīgi, sezonāli mikrobiotopi, gan relatīvi apdraudētiem biotopiem. Jūras un iesāļu augteņu biotopi ilglaicīgi biotopi, gan dažāda lieluma biotopu kompleksi. nodrošina Baltijas jūras austrumu piekrastei raksturīgo sugu Šie biotopi ir vienoti funkcionējošs komplekss, kas veido un sabiedrību kompleksa saglabāšanos. Šīs sabiedrības veido jūras krastam paralēlas dažāda platuma joslas. Baltijas jūras jūras un vēja pastāvīgai ietekmei, iesāļiem vides apstākļiem piekrastē biotopu joslas ir platākas nekā Rīgas jūras līča un mainīgam mitruma režīmam piemērojušās sugas. Viena krastos. no dažām litorālo augu sugu dabiskajām augtenēm Latvijā. Jūras un tās piekrastes biotopi ir pastāvīgi un vienlaikus ļoti Nelielā sugu skaita un dinamisko apstākļu dēļ šīs sabiedrības dinamiski. Ja pludmali intensīvi pārskalo jūras ūdens un ir ļoti jutīgas pret cilvēka -

Die Palpenmotten Nordwest-Deutschlands

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Faunistisch-Ökologische Mitteilungen Jahr/Year: 2000-2007 Band/Volume: 8 Autor(en)/Author(s): Wegner Hartmut, Kayser Christoph, Loh Hans-Joachim van Artikel/Article: Die Palpenmotten Nordwest-Deutschlands - eine Dokumentation der Beobachtungen in den Jahren 1981 - 2006 (Lepidoptera: Ge- lechiidae) 417-438 ©Faunistisch-Ökologische Arbeitsgemeinschaft e.V. (FÖAG);download www.zobodat.at Faun.-Ökol.Mitt. 8, 417-438 Kiel, 2007 Die Palpenmotten Nordwest-Deutschlands - eine Dokumentation der Beobachtungen in den Jahren 1981 - 2006 (Lepidoptera: Ge- lechiidae) VonHartmut Wegner, Christoph Kayser & Hans-Joachim van Loh Summary The gelechiid moths of North-West Germany - a documentation of records made between 1981 and 2006 (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) As a result of recent observations, a first and special synopsis to the fauna of Gelechii dae in North-western Germany is compiled. Particularly remarkable species are pre sented and commented to supplementary. A checklist of all species is attached. New bionomie knowledge of some species is described, i.e. Xenolechia aethiops (H umphreys & W estwood , 1845). The zoo-geographic status of some individual species as bore- omontan is revised, i.e. Neofaculta infernella (H errich-Schàffer, 1854). A checklist of all other observed species is attached Einleitung Die Region Nordwest-Deutschland ist ein eiszeitlich geprägtes Tiefland mit höchsten Erhebungen von 169 m (Wilseder Berg in der Lüneburger Heide) und 168 m (Bungsberg in Ostholstein) über N.N., und umfasst die Bundesländer Schleswig- Holstein und das nördliche Niedersachsen inkl. Hamburg und Bremen. Die Grenze bilden im Norden Dänemark sowie die Nordsee- und Ostseeküste, im Westen die Niederlande, im Osten die Bundesländer Mecklenburg-Vorpommern und Sachsen- Anhalt und im Süden die Linie von 52° 30' nördlicher Breite. -

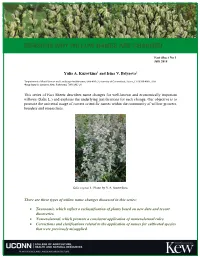

Reasons Why Willow Names Are Changed

REASONS WHY WILLOW NAMES ARE CHANGED Fact Sheet No 1 July 2018 Yulia A. Kuzovkina1 and Irina V. Belyaeva2 1Department of Plant Science and Landscape Architecture, Unit-4067, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269-4067, USA 2Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, TW9 3AE, UK This series of Fact Sheets describes name changes for well-known and economically important willows (Salix L.) and explains the underlying justifications for each change. Our objective is to promote the universal usage of correct scientific names within the community of willow growers, breeders and researchers. Salix repens L. Photo by Y.A. Kuzovkina. There are three types of willow name changes discussed in this series: Taxonomic, which reflect a reclassification of plants based on new data and recent discoveries. Nomenclatural, which promote a consistent application of nomenclatural rules. Corrections and clarifications related to the application of names for cultivated species that were previously misapplied. Taxonomic changes: Taxonomists through their research identify and describe taxa at all levels (in Salicaceae s.str. – mostly at the specific and infra-specific levels) revealing phylogenetic patterns. Modern techniques, especially morphological and molecular, are used to resolve disputed relationships among taxa, which result in a change of rankings of previously described taxa. When new information accumulates regarding the assignment of plants to specific taxa, reclassifications of organisms may take place leading to new orderings. For example, a morphological study into the group of plants that has been historically named as Salix fragilis revealed two different taxa in this group, which were proposed to be named as S. euxina I.V.Belyaeva and its hybrid with S. -

Nepticulidae from the Volga and Ural Region

Nieukerken_Nepticulidae _ final 17.12.2004 11:09 Uhr Seite 125 Nota lepid. 27 (2/3): 125–157 125 Nepticulidae from the Volga and Ural region ERIK J. VAN NIEUKERKEN1, VADIM V. Z OLOTUHIN2 & ANDREY MISTCHENKO2 1 National Museum of Natural History Naturalis PO Box 9517, NL-2300 RA Leiden, Netherlands, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Ulyanovsk State Pedagogical University, pl. 100-letiya Lenina 4, RUS-432700 Ulyanovsk, Russia, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The Nepticulidae of the Russian provinces (oblasts) Ul’yanovsk, Samara, Saratov, Volgograd, Astrakhan and Chelyabinsk and the Kalmyk Republic are listed. We record 60 species, including two only previously recorded, 28 species only on the basis of leafmines (indicated with an *). Seventeen species are recorded as new for Russia. Eleven of these are reported on the basis of adults: Stigmella glutinosae (Stainton, 1858), S. ulmiphaga (Preissecker, 1942), S. thuringiaca (Petry, 1904), S. rolandi Van Nieukerken, 1990, S. hybnerella (Hübner, 1813), Trifurcula (Trifurcula) subnitidella (Duponchel, 1843), T. (T.) silviae Van Nieukerken, 1990, T. (T.) beirnei Puplesis, 1984, T. (T.) chamaecytisi Z. & A. La√tüvka, 1994, Ectoedemia (Zimmermannia) liebwerdella Zimmermann, 1940 and Ectoedemia (Ectoedemia) caradjai (Groschke, 1944). Six species are reported on the basis of mines only: Stigmella freyella (Heyden, 1858), S. nivenburgensis (Preissecker, 1942), S. paradoxa (Frey, 1858), S. perpygmaeella (Doubleday, 1859), Ectoedemia (Ectoedemia) atricollis (Stainton, 1857) and E. spinosella (Joannis, 1908). Astigmella dissona Puplesis, 1984 is synonymised with Stigmella naturnella (Klimesch, 1936), here recorded for European Russia for the first time, bridging the gap between Far East Russia and Europe. S. juryi Puplesis, 1991 is synonymised with S.