A Daring Declaration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC Documents Creation of Israel DBQ Document A

AC Documents Creation of Israel DBQ Document A SOURCE: Torah portion, Lekh L'kha, taken from the Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures. The Jewish Publication Society. Philadelphia, PA. 1985. Genesis 12:1 - 7 1 The Lord said to Abram, Go forth from your native land and from your father's house to the land that I will show you. 2 I will make of you a great nation, And I will bless you; I will make your name great, And you shall be a blessing. 3 I will bless those who bless you And curse him that curses you; And all the families of the earth Shall bless themselves by you." 4 Abram went forth as the Lord had commanded him, and Lot went with him. Abram was seventy-five years old when he left Haran. 5 Abram took his wife Sarai and his brother's son Lot, and all the wealth that they had amassed, and the persons that they had acquired in Haran; and they set out for the land of Canaan. When they arrived in the land of Canaan, 6 Abram passed through the land as far as the site of Shechem, at the terebinth of Moreh. The Canaanites were then in the land. 7 The Lord appeared to Abram and said, "I will assign this land to your heirs." And he built an altar there to the Lord who had appeared to him. AC Documents Creation of Israel DBQ Document B SOURCE: published in the Official Gazette: Number 1; Tel Aviv, 5 Iyar 5708, 14.5.1948. -

The Religious Meaning of Israel Rosh Hashanah 5775 Day 1, September 25, 2014 R

The Religious Meaning of Israel Rosh Hashanah 5775 Day 1, September 25, 2014 R. Steven A. Lewis As many of you know, I went to Israel this summer for a very brief visit. At the core of it, I wanted to be there in solidarity with friends and the whole country during a difficult period. I found the article I sent out to the membership written by my friend Bonna Haberman very compelling. In this article she encouraged people who cared about Israel to express their concerns in person. She wrote that she understood it was inconvenient, but she hadn't planned to spend the summer in a bomb shelter worrying about her three sons in active duty in the army. I am so grateful that I was able to go. Another reason for the trip was to visit a friend who is battling a very serious illness. So I was also fulfilling the mitzvah of Bikor Holim, "visiting the sick." In discussing this mitzvah, the Talmud says One who visits the sick must not sit upon the bed, or on a stool or a chair, but must be respectfully dressed and sit upon the ground, because the Divine Presence rests above an invalid's bed. (Bavli Nedarim 40a) מפני שהשכינה שרויה למעלה ממטתו של חולה So those images raise the interesting question of God's location. The liturgy is inconsistent on this point, most specifically it identifies God as Shochain Yerushalyim "The One who dwells in Jerusalem," but also, in the very same passage as "the One whose presence fills all of creation." I'd like to talk about Israel today. -

Palestine About the Author

PALESTINE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Professor Nur Masalha is a Palestinian historian and a member of the Centre for Palestine Studies, SOAS, University of London. He is also editor of the Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. His books include Expulsion of the Palestinians (1992); A Land Without a People (1997); The Politics of Denial (2003); The Bible and Zionism (Zed 2007) and The Pales- tine Nakba (Zed 2012). PALESTINE A FOUR THOUSAND YEAR HISTORY NUR MASALHA Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History was first published in 2018 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK. www.zedbooks.net Copyright © Nur Masalha 2018. The right of Nur Masalha to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by seagulls.net Index by Nur Masalha Cover design © De Agostini Picture Library/Getty All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑272‑7 hb ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑274‑1 pdf ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑275‑8 epub ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑276‑5 mobi CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 1. The Philistines and Philistia as a distinct geo‑political entity: 55 Late Bronze Age to 500 BC 2. The conception of Palestine in Classical Antiquity and 71 during the Hellenistic Empires (500‒135 BC) 3. -

—PALESTINE and the MIDDLE EAST-N

PALESTINE AND MIDDLE EAST 409 —PALESTINE AND THE MIDDLE EAST-n By H. Lowenberg— PALESTINE THE YEAR BEGINNINO June, 1947, and ending May, 1948 was among the most crucial and critical periods in Palestine's modern history. The United Nations' historic partition decision of November 29, 1947, divided the year into two halves, each of different importance for the Yishuv and indeed for all Jewry: the uneasy peace before, and the commu- nal war after the UN decision; the struggle to find a solution to the Palestine problem before, and to prepare for and defend the Jewish state after that fateful day. Outside Palestine, in the Middle East as a whole, the UN partition decision and the Arab rebellion against it, left a mark scarcely less profound than in Palestine itself. UNSCOP On May 13, 1947, the special session of the General As- sembly of the United Nations created the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) with instructions to "prepare and report to the General Assembly and submit such proposals as it may consider appropriate for the solution of the problem of Palestine . not later than September ,1, 1947." In Palestine, the Arabs followed news of UNSCOP with apparent indifference. They adopted an attitude of hostil- ity towards the Committee, and greeted it with a two-day protest strike starting on June 15, 1947. Thereafter, they 410 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK took no further notice of the Committee, the Arab press even obeying the Mufti's orders not to print any mention of UNSCOP. This worried the Committee, as boycott by one side to the dispute might mean a serious gap in its fact finding. -

List of the Archives of Organizations and Bodies Held at the Central

1 Guide to the Archival Record Groups and Collections Notation Record group / Collection Dates Scanning Quantity 1. Central Offices of the World Zionist Organization and of the Jewish Agency for Palestine/Israel abroad Z1 Central Zionist Office, Vienna 1897-1905 scanned 13.6 Z2 Central Zionist Office, Cologne 1905-1911 scanned 11.8 not Z3 Central Zionist Office, Berlin 1911-1920 31 scanned The Zionist Organization/The Jewish Agency for partially Z4 1917-1955 215.2 Palestine/Israel - Central Office, London scanned The Jewish Agency for Palestine/Israel - American Section 1939 not Z5 (including Palestine Office and Zionist Emergency 137.2 onwards scanned Council), New York Nahum Goldmann's offices in New York and Geneva. See Z6 1936-1982 scanned 33.2 also Office of Nahum Goldmann, S80 not Z7 Mordecai Kirshenbloom's Office 1957-1968 7.8 scanned 2. Departments of the Executive of the World Zionist Organization and the Jewish Agency for Palestine/Israel in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv and Haifa not S1 Treasury Department 1918-1978 147.7 scanned not S33 Treasury Department, Budget Section 1947-1965 12.5 scanned not S105 Treasury Department, Section for Financial Information 1930-1959 12.8 scanned partially S6 Immigration Department 1919-1980 167.5 scanned S3 Immigration Department, Immigration Office, Haifa 1921-1949 scanned 10.6 S4 Immigration Department, Immigration Office, Tel Aviv 1920-1948 scanned 21.5 not S120 Absorption Department, Section for Yemenite Immigrants 1950-1957 1.7 scanned S84 Absorption Department, Jerusalem Regional Section 1948-1960 scanned 8.3 2 Guide to the Archival Record Groups and Collections not S112 Absorption Department, Housing Division 1951-1967 4 scanned not S9 Department of Labour 1921-1948 25.7 scanned Department of Labour, Section for the Supervision of not S10 1935-1947 3.5 Labour Exchanges scanned Agricultural Settlement Department. -

The Signatories of the Israel Declaration of Independence

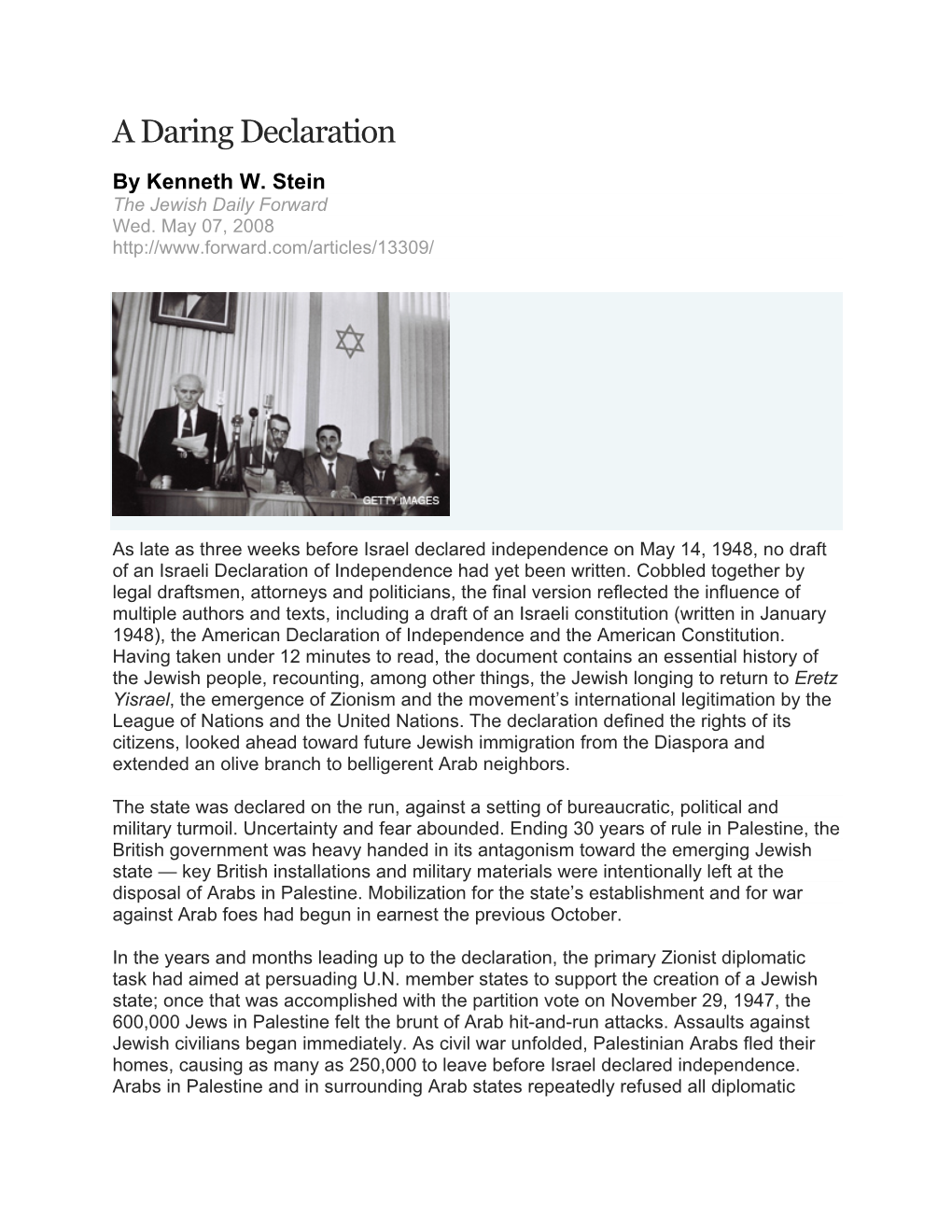

Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs The Signatories of the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel The British Mandate over Palestine was due to end on May 15, 1948, some six months after the United Nations had voted to partition Palestine into two states: one for the Jews, the other for the Arabs. While the Jews celebrated the United Nations resolution, feeling that a truncated state was better than none, the Arab countries rejected the plan, and irregular attacks of local Arabs on the Jewish population of the country began immediately after the resolution. In the United Nations, the US and other countries tried to prevent or postpone the establishment of a state, suggesting trusteeship, among other proposals. But by the time the British Mandate was due to end, the United Nations had not yet approved any alternate plan; officially, the partition plan was still "on the books." A dilemma faced the leaders of the yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine. Should they declare the country's independence upon the withdrawal of the British mandatory administration, despite the threat of an impending attack by Arab states? Or should they wait, perhaps only a month or two, until conditions were more favorable? Under the leadership of David Ben-Gurion, who was to become the first Prime Minister of Israel, theVa'ad Leumi - the representative body of the yishuv under the British mandate - decided to seize the opportunity. At 4:00 PM on Friday, May 14, the national council, which had directed the Jewish community's affairs under the British Mandate, met in the Tel Aviv Museum on Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv. -

Israel's Rights As a Nation-State in International Diplomacy

Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Institute for Research and Policy המרכז הירושלמי לענייני ציבור ומדינה )ע"ר( ISRAEl’s RiGHTS as a Nation-State in International Diplomacy Israel’s Rights as a Nation-State in International Diplomacy © 2011 Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs – World Jewish Congress Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 13 Tel Hai Street, Jerusalem, Israel Tel. 972-2-561-9281 Fax. 972-2-561-9112 Email: [email protected] www.jcpa.org World Jewish Congress 9A Diskin Street, 5th Floor Kiryat Wolfson, Jerusalem 96440 Phone : +972 2 633 3000 Fax: +972 2 659 8100 Email: [email protected] www.worldjewishcongress.com Academic Editor: Ambassador Alan Baker Production Director: Ahuva Volk Graphic Design: Studio Rami & Jaki • www.ramijaki.co.il Cover Photos: Results from the United Nations vote, with signatures, November 29, 1947 (Israel State Archive) UN General Assembly Proclaims Establishment of the State of Israel, November 29, 1947 (Israel National Photo Collection) ISBN: 978-965-218-100-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Overview Ambassador Alan Baker .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The National Rights of Jews Professor Ruth Gavison ........................................................................................................................................................................... 9 “An Overwhelmingly Jewish State” - From the Balfour Declaration to the Palestine Mandate -

Rene Cassin Fellowship Program Rene Cassin RCFP Israel Hub

René Cassin Fellowship Program Israel Study Tour June 4-12, 2013 Program Booklet “THE STATE OF ISRAEL will be open for Jewish immigration and for the Ingathering of the Exiles; it will foster the development of the country for the benefit of all its inhabitants; it will be based on freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel; it will ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex; it will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture; it will safeguard the Holy Places of all religions; and it will be faithful to the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.” Excerpt from Israel’s Declaration of Independence Contents: Page 3 Goals of the René Cassin Fellowship Program (RCFP) Page 5 Our Partners Page 6 Program Itinerary Page 11 Biographies of speakers and organisations Page 20 Minorities of Israel Page 22 The Declaration of Independence Page 25 Blank pages for notes 2 Goals of the RCFP: 1) To deepen and broaden participant’s knowledge, understanding and engagement of Jewish visions of a just society through the study of Jewish classical and modern sources and contemporary international human rights law. 2) To wrestle with the dilemmas and value-conflicts raised by the interplay of international human rights law, Jewish tradition and the contemporary social and political reality of the Jewish People and the State of Israel. This will be achieved through the examination of examples from Israel, diaspora Jewish communities and other societies. 3) To strengthen the social capital of the Jewish people by engaging socially/politically active young Jews from three continents in a program of study, cross-cultural dialogue, travel, and internships. -

Israel 54360. Young State

-, .. ,:i -,~ , . , _ It. ,_ th. ",0{(' i . I , -, - . , " , " .' " TIllttsday, A'Ugust,24, 1900'· SEP 1ra50 THE JEWISH POST .. - ", - -.' ' -". ,- ~.' '. - nGurion/s New Stand On. Gal '~th S, . J.Dniche . 'as diScussion . Rabbi •Arthur' Chiel' "leader. -,'. " , . ' . Room and Board Room and Board Wanted 'f!;~~~!o~~n:uTt:~!~ !:. ~e:!! At North' End Schute" Mrs. 0:. P. potlieb will pre~de Room' and bOard in nice home. Home w~nted' for. young man tric stove.. Suitable. for couple, 222 Holiday ServiCe • . at' ,,:'the' luncheon' .sessioll7'- and "-Mr. OnSunday/sWestern Zoc Student preferred. Apply 321' Magnus entering .first year university, Will Pritchard Ave.· .. ..' .' Green' at the dinner.' .' .' .'. avenue .. Phone 590005. be. in Winnipeg first week. in Sept, . RabbiSch)V8rlz has recently re • to make arrangements. ,Write to Room for .,Rent turned'from Isr.ael.and it is expecte<i Ben 'Gurion's recent his... Suite to Share Mrs, H, A. Breslaw, Dauphin, Man. Room for rent,· with or '1;~~;1 that he' willgiv'e·8 ¢Otnprehensive ipcllic,y statement on the rela ! Young man under thirty wanted . -_.... board. Suitable f{)rstudent. report of"the . problems facmg tli.e "·world Jewry "-'.to Israel 54360._ young state. ~: I to share 4-room furnished apart- .Suite for R~t-2 Students last week, Will' be aired , '. I :went in central location. Reasonable Private suite for rent, suitable for SIGMA ALPHA:-·l.mJ-'--~i. for the first time by Zionist II rent. Box 163. two students. Exceptionally come '. (Cont; from page 1) .' Canada when ZOC Na 1/ of the Mid dustiee Batshaw 11 Furnished Room for Rent :;fo:;.rta.::::;b:;:;le;.:h::;;om::::;;e;;.;.;,Ph:.::o~n:::e.:58:::.::034::;;.' .... -

The Transfer Agreement and the Boycott Movement: a Jewish Dilemma on the Eve of the Holocaust

The Transfer Agreement and the Boycott Movement: A Jewish Dilemma on the Eve of the Holocaust Yf’aat Weiss In the summer of 1933, the Jewish Agency for Palestine, the German Zionist Federation, and the German Economics Ministry drafted a plan meant to allow German Jews emigrating to Palestine to retain some of the value of their property in Germany by purchasing German goods for the Yishuv, which would redeem them in Palestine local currency. This scheme, known as the Transfer Agreement or Ha’avarah, met the needs of all interested parties: German Jews, the German economy, and the Mandatory Government and the Yishuv in Palestine. The Transfer Agreement has been the subject of ramified research literature.1 Many Jews were critical of the Agreement from the very outset. The negotiations between the Zionist movement and official representatives of Nazi Germany evoked much wrath. In retrospect, and in view of what we know about the annihilation of European Jewry, these relations between the Zionist movement and Nazi Germany seem especially problematic. Even then, however, the negotiations and the agreement they spawned were profoundly controversial in broad Jewish circles. For this reason, until 1935 the Jewish Agency masked its role in the Agreement and attempted to pass it off as an economic agreement between private parties. One of the German authorities’ principal goals in negotiating with the Zionist movement was to fragment the Jewish boycott of German goods. Although in retrospect we know the boycott had only a marginal effect on German economic 1 Eliahu Ben-Elissar, La Diplomatie du IIIe Reich et les Juifs (1933-1939) (Paris: Julliard, 1969), p. -

Religion in Israel

Religion in Israel by Zvi YARON THE CONTROVERSY R.ELIGIO, N in the State of Israel has become noted for its poten- tial to generate strife. The frequent controversies over its role in society, an issue affecting the most sensitive areas of Israeli life, are acrimonious and harsh in tone. Many of them are accompanied by demonstrations and spiteful incidents instigated by extremists of all shades and opinions, rang- ing from the zealous Neture Karta to the frenetic League for the Prevention of Religious Coercion. No doubt, they reflect the acerbated feelings of many moderate Israelis. Religious disputes have arisen over education, the legal definition of "who is a Jew," the authority of the rabbinate, autopsies, marriage and divorce, the legal status of the common-law wife, the status of women, army service for girls and yeshivah students, Sabbath observ- ance, kashrut, the prohibition of pig-raising, and the closing of cinemas and theaters on religious holidays. Some people complain that Israel is a theocracy, arguing that religion intrudes into every important aspect of public and individual life and im- poses its authority on the governing of the state.1 At the same time, there is the often-heard lament that Israel is a radically secularist state, in which the religious areas are narrowly circumscribed and the decisive influences 'On the complexities of the meaning of theocracy (first used by Josephus in his Against Apion) and its application to modern Israel, see Mordecai Roshwald, "Theocracy in Israel in Antiquity and Today," Jewish Journal of Sociology, Vol. 14, No. 1, June 1972, pp. -

Zionism & Israel As the Nation-State of the Jewish People

Zionism & Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People CUTTING THROUGH THE CONFUSION BY GOING BACK TO BASICS A Resource for the Global Jewish World Zionism & Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People CUTTING THROUGH THE CONFUSION BY GOING BACK TO BASICS A Resource by The Israel Forever Foundation THE PROBLEM The debates surrounding Zionism, Israel, and the legitimacy of a Nation State for the Jewish People seem never ending. The foundations on which the Jewish State was founded are constantly being questioned – both by the anti-Israel movement as well as within the Jewish world. Is Zionism racism? Is the word “Zionist” an insult? More and more people seem to think so. Social media’s magnification of individual voices has blurred the lines between what were until very recently extremist views one would not publicly express and narrative that is being expressed on college campuses, political pulpits and even mainstream media. Are we equipped to answer these accusations? Do we want to? How can we prepare the next generations to handle what is coming? In a time of pluralism and globalism, is the Jewish State legitimate? The legitimacy of the Jewish State has been questioned since (before) her establishment. The recent passing of Israel’s Nation State Law has been the impetus for renewed questioning. Many in the Jewish world have felt uneasy about the law, fearing it undermines the inherent pluralism of the Jewish State. What is the balance between Jewish Nationalism, Israel as a homeland for the Jewish People and Israel as a modern, liberal and pluralist country? What are the concerns? How should they be addressed? Confusion within the Jewish world We know that antisemitism is on the rise.