Boonman, A.M.J. 1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAST of CHARACTERS Tweedlenee .QUEEN-G

AUCE IN WONDERLAND Adapted from the works of Lewis Carroll CAST OF CHARACTERS AUCE \v..l J ' MRS. MUMFORD, Alice's Governess .. TWEEDLEnEE .QUEEN-G~ DUCHI<SS ~ KNAVEOFHEARTS 1":j MAD HA'ITER 'B DORMOUSE ' • ACTI SCENE l:A ROOM IN ALICE'S HOUSE Rabbits Don't Carry Watches ................................ Mrs. Mumford & Alice Wonderland White Rabbit & Alice Journey To Wonderland The Company SCENE 2:V ARlO US LOCATIONS IN WONDERLAND WonderfuL .........•....•..................••.•..•.•..•.••.•..•.••••. Caterpillar Never Seen An Egg Like That Tweedledee, Tweedledum, Alice Lullaby Duchess, Queen. White Rabbit A Ball at the Palace Alice, Queen. White Rabbit. Knave, Caterpillar ACT II SCENE l:THE MAD HATTER'S GARDEN Four O'Cloclc Tea. ...............................................Mad Hatter & Dormouse Soon You'll See The Sun Alice, Caterpillar, Knave The Trial The Company SCENE 2:A ROOM IN ALICE'S HOUSE Watch.es (reprise) .................................................Alice Finale The Company ., THE UGHTS COME UP DOWNSTAGE AND WE SEE AUCE SEATED AT A DRESSING TABLE. TIIE MIRROR ON THE TABLE IS SHAPED VERY MUCH LIKE A LARGE HAND-MIRROR. AUCE IS A YOUNG GrRL SOMEWHERE BElWEEN THE AGES OF TEN AND TWELVE YEARS OLD AND IS DRESSED IN CLOTHES APPROPRIATE FOR A YOUNG GIRL UVING IN THE GENTRIDED ENGUSH COUNTRYSIDE OF THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY. UPSTAGE IN THE SHADOWS THERE ARE SHAPES WE CANNOT MAKE OUT Bur WllL LATER BE SEEN AS 1HE •MARKERS* OF •woNDERLAND.• WE HEAR VOICES UGHTLY CAlLING Our TO AUCE. SHE IS NOT SURE WHAT SHE IS HEARING. OFFSTAGE VOICE (singing) A1ice....Aiice AUCE What? Who called? OFFSTAGE VOICE (singing) THAT'S THE WAY, YOU SEE NEVER TO MISS•••• AUCE. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Cast List- Alice in Wonderland Alice- Rachel M. Mathilda- Chynna A

Cast List- Alice in Wonderland Alice- Rachel M. Mathilda- Chynna A. Cheshire Cat 1- Jelayshia B. Cheshire Cat 2- Skylar B. Cheshire Cat 3- Shikirah H. White Rabbit- Cassie C. Doorknob- Mackenzie L. Dodo Bird- Latasia C. Rock Lobsters & Sea Creatures- Kayla M., Mariscia M., Bar’Shon B., Brandon E., Camryn M., Tyler B., Maniya T., Kaitlyn G., Destiney R., Sole’ H., Deja M. Tweedle Dee- Kayleigh F. Tweedle Dum- Tynigie R. Rose- Kristina M. Petunia- Cindy M. Lily- Katie B. Violet- Briana J. Daisy- Da’Johnna F. Flower Chorus- Keonia J., Shalaya F., Tricity R. and named flowers Caterpillar- Alex M. Mad Hatter- Andrew L. March Hare- Glenn F. Royal Cardsmen- ALL 3 Diamonds- Shemar H. 4 Spades- Aaron M. Ace Spades- Kevin T. 5 Diamonds- Abraham S. 2 Clubs- Ben S. Queen of Hearts- Alyceanna W. King of Hearts- Ethan G. Ensemble/Chorus- Katie B. Kevin T. Ben S. Briana J. Kristina M. Latasia C. Da’Johnna F. Shalaya F. Shamara H. Shemar H. Cindy M. Keonia J. Tricity R. Kaitlyn G. Sole’ H. Aaron M. Deja M. Destiney R. Abraham S. Chanyce S. Kayla M. Camryn M. Destiney A. Tyler B. Mariscia M. Brandon E. Bar’Shon B. Bridgette B. Maniya T. Amari L. Dodgsonland—ALL I’m Late—4th Very Good Advice—4th Grade Ocean of Tears—Dodo, Rock Lobsters, Sea Creatures (select 3rd and 4th) I’m Late-Reprise—4th How D’ye Do and Shakes Hands—Tweedles and Alice The Golden Afternoon—5th Grade girls Zip-a-dee-do-dah—4th and 5th The Unbirthday Song—5th Grade Painting the Roses Red—ALL Simon Says—Queen, Alice (ALL cardsmen) The Unbirthday Song-Reprise—Mad Hatter, Queen, King, 5th Grade Who Are You?—Tweedles, Flowers, Alice, Mad Hatter, White Rabbit, Queen & Named Cardsmen Alice in Wonderland: Finale—ALL Zip-a-dee-doo-dah: Bows—ALL . -

Walt Disneys Alice in Wonderland Free

FREE WALT DISNEYS ALICE IN WONDERLAND PDF Rh Disney | 24 pages | 05 Jan 2010 | Random House USA Inc | 9780736426701 | English | New York, United States Alice in Wonderland | Disney Movies Published by Simon and Schuster. Seller Rating:. About this Item: Simon and Schuster. Condition: Fair. First edition copy. Reading copy only. Spine Walt Disneys Alice in Wonderland. Seller Inventory Q12C More information about this seller Contact this seller 1. Condition: Near Fine. First Thus. Illustrated Glazed Board Covers; Covers are clean and bright; Walt Disneys Alice in Wonderland right front corner is rubbed and spine panel has a small chip at gutter edge near bottom; Pictorial endpapers; Fixed front endpaper has previous owner's name in upper left corner; Book interior is clean and tight and unmarked; 4to; 96 pages. Seller Inventory More information about this seller Contact this seller 2. Pictorial Cover. Condition: Poor. No Jacket. The Walt Disney Studio illustrator. Color and three color illust. Pages yellowed. Hairline tears on pages. Pen markings on title page. Owners name inscribed on inside of front cover. Spine worn. Covers worn around edges. Corners of covers bent. Seller Inventory B. More information about this seller Contact this seller 3. Published by Disney Enterprises, US Condition: Fine. More information about this seller Contact this seller 4. Cloth Hardbound. Condition: Near Very Good. Walt Disney Studios illustrator. First Edition. Unpaginated Interior is clean, bright and Walt Disneys Alice in Wonderland Small scribble on front cover Wear at corners of cover Small chips at base of spine. More information about this seller Contact this seller 5. -

Alice in Wonderland

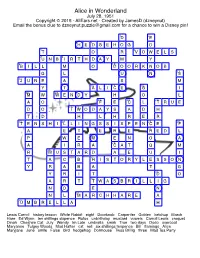

Alice in Wonderland July 28, 1951 Copyright © 2015 - AllEars.net - Created by JamesD (dzneynut) Email the bonus clue to [email protected] for a chance to win a Disney pin! 1 2 D E 3 4 H E D G E H O G D 5 6 T O R V O W E L S 7 8 U N B I R T H D A Y M Y 9 10 B I L L M O D O O R K N O B 11 G L U N S 12 J U N E A S M 13 14 15 Y T A L I C E G I 16 17 M W W E N D Y H O L 18 19 20 A O F E C L T R U E 21 22 D O T W O D A Y S A D H T D H L H R E R 23 24 25 26 T E N S H I L L I N G S S I X P E N C E F 27 A E T E R E R E D L 28 P W E M E N O A 29 A I R A C A T Q M 30 R M U S T A R D A E U I 31 T A C B H I S T O R Y L E S S O N Y R A B A T G 32 Y R I T D O 33 A R T T W A S B R I L L I G N O E N 34 N L M A R C H H A R E A 35 U M B R E L L A H Lewis Carroll history lesson White Rabbit eight Doorknob Carpenter Golden ketchup March Hare Ed Wynn ten shillings sixpence Rufus unbirthday mustard vowels Carroll Lewis croquet Dinah Cheshire Cat July Wendy Im Late umbrella smirk True two days Dodo overcoat Maryanne Tulgey Woods Mad Hatter cat red six shillings tenpence Bill flamingo Alice Maryjane June smile False bird hedgehog Dormouse Twas Brillig three Mad Tea Party ★ Thurl Ravenscroft, a member of the singing group, the Mellomen, who sing #27 Across, appears to have lost his head while singing a familiar song in what popular theme park attraction? (2 words) [HAUNTEDMANSION] Across Down 3. -

Chapter 1: Mattes and Compositing Defined Chapter 2: Digital Matting

Chapter 1: Mattes and Compositing Defined Chapter 2: Digital Matting Methods and Tools Chapter 3: Basic Shooting Setups Chapter 4: Basic Compositing Techniques Chapter 5: Simple Setups on a Budget Chapter 6: Green Screens in Live Broadcasts Chapter 7: How the Pros Do It one PART 521076c01.indd 20 1/28/10 8:50:04 PM Exploring the Matting Process Before you can understand how to shoot and composite green screen, you first need to learn why you’re doing it. This may seem obvious: you have a certain effect you’re trying to achieve or a series of shots that can’t be done on location or at the same time. But to achieve good results from your project and save yourself time, money, and frustration, you need to understand what all your options are before you dive into a project. When you have an understanding of how green screen is done on all levels you’ll have the ability to make the right decision for just about any project you hope to take on. 521076c01.indd 1 1/28/10 8:50:06 PM one CHAPTER 521076c01.indd 2 1/28/10 8:50:09 PM Mattes and Compositing Defined Since the beginning of motion pictures, filmmakers have strived to create a world of fantasy by combining live action and visual effects of some kind. Whether it was Walt Disney creating the early Alice Comedies with cartoons inked over film footage in the 1920s or Ray Harryhausen combining stop-motion miniatures with live footage for King Kong in 1933, the quest to bring the worlds of reality and fantasy together continues to evolve. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit “Alice’s Journey Through Utopian and Dystopian Wonderlands“ verfasst von Katharina Fohringer, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 344 333 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Lehramtsstudium Englisch, Deutsch Betreut von: o.Univ.-Prof. Dr. Margarete Rubik TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 3 2. ADAPTATION THEORY ................................................................................ 5 2.1. Defining and Categorizing Adaptations .................................................... 5 2.2. Approaches to Analysis ............................................................................ 8 2.2.1. Meaning and Reality .......................................................................... 8 2.2.2. Narrative, Time and Space .............................................................. 11 2.2.3. Film Techniques............................................................................... 14 3. UTOPIA AND DYSTOPIA ON SCREEN...................................................... 16 3.1. Definitions .............................................................................................. 16 3.2. Historical Development of Utopia in Film ............................................... 18 3.3. Categories for Analysis .......................................................................... 21 4. FILM ANALYSIS ......................................................................................... -

Through the Mirror Free

FREE THROUGH THE MIRROR PDF G. M. Berrow | 224 pages | 02 Oct 2014 | Hachette Children's Group | 9781408336601 | English | London, United Kingdom Through the Looking-Glass - Wikipedia From " Veronica Mars " to Rebecca take a look back at the career of Armie Hammer on and off the screen. See the full gallery. Biographical documentary of Lee Miller aka Elizabeth Miller,her early years in USA under her father's influence, later became a model turned artist and celebrated photographer, including her photojournalism during WWII, and her second marriage to British surrealism painter Roland Penrose postwar. Film is told through interviews with Miller's son, Antony Penrose. The various phases of Lee Miller's life and works are accounted and revealed by writer-director Sylvain Roumette, with the collaboration of Lee's son, Antony Penrose, Lee's Through the Mirror wartime journalist friend David Scherman, and Patsy I. Murray whom Lee brought in as the 'second mother' to Through the Mirror. Early in the film: "I longed to be loved, just once, somewhat purely and chastely, to have youth and innocence so. The film provided personal insights and fond reminiscences of their times with Lee from Antony, Scherman and Murray. And by the end, we can tell that Antony Penrose, with the help and understanding of Scherman, is resolved with his differences towards his mother. Anyone who appreciates photography, art, surrealism, Man Ray, woman influences, or simply a worthwhile documentary - do check out Through the Mirror film available on DVD. The "Portfolio" option gives a photo synopsis of the eight stages of Lee Miller's life. -

Factualwritingfinal.Pdf

Introduction to Disney There is a long history behind Disney and many surprising facts that not many people know. Over the years Disney has evolved as a company and their films evolved with them, there are many reasons for this. So why and how has Disney changed? I have researched into Disney from the beginning to see how the company started and how they got their ideas. This all lead up to what happened in the company including the involvement of pixar, and how the Disney films changed in regards to the content and the reception. Now with the relevant facts you can make up your own mind about when Disney was at their best. Walt Disney Studios was founded in 1923 by brothers Walt Disney and Roy O. Disney. Originally Disney was called ‘Disney Brothers cartoon studio’ that produced a series of short animated films called the Alice Comedies. The first Alice Comedy was a ten minute reel called Alice’s Wonderland. In 1926 the company name was changed to the Walt Disney Studio. Disney then developed a cartoon series with the character Oswald the Lucky Rabbit this was distributed by Winkler Pictures, therefore Disney didn’t make a lot of money. Winkler’s Husband took over the company in 1928 and Disney ended up losing the contract of Oswald. He was unsuccessful in trying to take over Disney so instead started his own animation studio called Snappy Comedies, and hired away four of Disney’s primary animators to do this. Disney planned to get back on track by coming up with the idea of a mouse character which he originally named Mortimer but when Lillian (Disney’s wife) disliked the name, the mouse was renamed Mickey Mouse. -

Chapter Template

Copyright by Colleen Leigh Montgomery 2017 THE DISSERTATION COMMITTEE FOR COLLEEN LEIGH MONTGOMERY CERTIFIES THAT THIS IS THE APPROVED VERSION OF THE FOLLOWING DISSERTATION: ANIMATING THE VOICE: AN INDUSTRIAL ANALYSIS OF VOCAL PERFORMANCE IN DISNEY AND PIXAR FEATURE ANIMATION Committee: Thomas Schatz, Supervisor James Buhler, Co-Supervisor Caroline Frick Daniel Goldmark Jeff Smith Janet Staiger ANIMATING THE VOICE: AN INDUSTRIAL ANALYSIS OF VOCAL PERFORMANCE IN DISNEY AND PIXAR FEATURE ANIMATION by COLLEEN LEIGH MONTGOMERY DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN AUGUST 2017 Dedication To Dash and Magnus, who animate my life with so much joy. Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the invaluable support, patience, and guidance of my co-supervisors, Thomas Schatz and James Buhler, and my committee members, Caroline Frick, Daniel Goldmark, Jeff Smith, and Janet Staiger, who went above and beyond to see this project through to completion. I am humbled to have to had the opportunity to work with such an incredible group of academics whom I respect and admire. Thank you for so generously lending your time and expertise to this project—your whose scholarship, mentorship, and insights have immeasurably benefitted my work. I am also greatly indebted to Lisa Coulthard, who not only introduced me to the field of film sound studies and inspired me to pursue my intellectual interests but has also been an unwavering champion of my research for the past decade. -

Motifs of Passage Into Worlds Imaginary and Fantastic

Motifs of Passage into Worlds Imaginary and Fantastic F. Gordon Greene Sacramento, CA ABSTRACT: In this paper I match phenomena associated with the passage into otherworlds as reported during out-of-body and near-death experiences, with imagery associated with the passage into otherworlds as depicted in classic modern fantasies and fairy tales. Both sources include sensations of consciousness separating from the body, floating and flying, passage through fluidic spaces or dark tunnels toward bright lights, and emergence into super natural worlds inhabited by souls of the deceased and by higher spiritual beings; and both describe comparable psychophysical initiatory factors. I intro duce a metaphysically neutral depth psychology to explain these parallels, examine two metaphysically opposed extensions to this depth psychology, and consider several implications of a transcendental perspective. Introduction The prospect of a fantastic journey leading into realms of super natural wonder has always fired the human imagination and probably always will. Such a journey may involve a voyage to remote islands or continents hidden in uncharted seas, a trek off the edge of the Earth's flat surface, a descent into the gloomy underworld below, an ascent into the starry heavens above, or a passage through a magical portal into dimensions unseen. Whatever the pathway, the possibility of such a fantastic journey speaks irresistibly to some deep facet of human nature, this is a facet possessed of a longing that must be appeased, if not fulfilled, in the realm of human imagination, if not in that of some extra mundane reality. Mr. Greene is a free-lance writer whose principal interests have been parapsychology, religion, and metaphysics. -

WOO HOO! Time to Par-Tay!!!

A Newsletter Exclusively for Disney Enthusiasts VOLUME 19 NO. 2 SUMMER, 2010 WOO HOO! Time to Par-tay!!! There will also be a selection of limited edition merchandise This year is the 55th anniversary of Disneyland Resort, and D23 available for purchase at the event. is celebrating this milestone year with the premiere of Destina- tion D: Disneyland ’55, a brand-new, two-day event that illumi- Here is the current lineup for Destination D: Disneyland ’55 nates the fascinating history behind Disney’s flagship park. FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 2010 Destination D: Disneyland ’55 will take D23 Members on a mesmerizing journey through Mickey Mouse Club 55th Anniversary the design, creation, debut and magical his- Join original Mouseketeers including Sharon Baird, tory of the world’s first Disney theme park. Doreen Tracey, Bobby Burgess, Karen Pendleton, The event will offer two full days of special Sherry Van Meter (Alberoni), Tommy Cole, Cubby presentations, panels, screenings and guest O’Brien and Mary Geoff (Espinosa) for a magi- speakers that give fans an inside view of cal walk down memory lane as they recall their this fascinating era in Disney history and favorite behind-the-scenes stories from the classic let them meet and talk with key figures in Disneyland attraction Mickey Mouse Club Circus. Disneyland’s history. Future Destination D events will explore other important aspects Weird Disney of Disney’s amazing creative legacy. Follow- From the startling visuals of the 1930s Fanchon ing its premiere in September, Destination & Marco “Mickey Mouse Idea” vaudeville shows D will alternate annually with the enor- to Disneyland’s “Kap the Kaiser Aluminum Pig” mously popular D23 Expo.