Motifs of Passage Into Worlds Imaginary and Fantastic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Kaleidoscope

The faculty advisors wish to give special recognition and thanks to these individuals who also gave of their time and energy to make this edition of the Kaleidoscope possible: Lauren Courtney, Jakob Plotts, and Tracy Snowman. Thank you! 2 Kaleidoscope Journal of Art & Literature -Editor- James Grove -Assistant Editors- Brie Coder Alexa Dailey Georgia Meagher Trista Miller Cameron Phillips -Faculty Advisors- Michael Maher Becca Werland -Cover Art- Brandy Wise 3 Alexa Dailey-17, 25 Alyssa Brown-28 Amber Burnett-8 Annalea Forrest-9, 11, 16, 18, 24 Aubrey Foust-6, 14, 20, 31 Brandy Wise-Cover Brie Coder-29 Cecilia Carrillo-12, 18 Edward Johnson-5, 9, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30 Frances G. Tate-32 Georgia Meagher-13 Jacqueline Westin-6,10, 12, 20, 26 Jakob Plotts-3, 5, 8, 21 James Grove-21, 32 Jed Vaughn-11 Lafe Richardson-10, 19 An Artist’s Still Life Paula Cortes-4 Jakob Plotts Sheretta S Miller-7, 15, 22 4 Letter from the Editor Life is filled with a variety of people; some are good and others bad. We have athletes, scholars, theatre progressives, metal heads, and far too many more to write down in the little space I have. The point is that life is filled with different walks of life, and perhaps that’s what I en- joy most about the Kaleidoscope. Within these pages, you, dear reader, will find people who’ve gained and lost, found joy and pain. You’ll find works of the sur- real, and still ones of reality. I give thanks to those who helped piece together the many to present something whole, for that is the heart of the Kaleidoscope. -

CAST of CHARACTERS Tweedlenee .QUEEN-G

AUCE IN WONDERLAND Adapted from the works of Lewis Carroll CAST OF CHARACTERS AUCE \v..l J ' MRS. MUMFORD, Alice's Governess .. TWEEDLEnEE .QUEEN-G~ DUCHI<SS ~ KNAVEOFHEARTS 1":j MAD HA'ITER 'B DORMOUSE ' • ACTI SCENE l:A ROOM IN ALICE'S HOUSE Rabbits Don't Carry Watches ................................ Mrs. Mumford & Alice Wonderland White Rabbit & Alice Journey To Wonderland The Company SCENE 2:V ARlO US LOCATIONS IN WONDERLAND WonderfuL .........•....•..................••.•..•.•..•.••.•..•.••••. Caterpillar Never Seen An Egg Like That Tweedledee, Tweedledum, Alice Lullaby Duchess, Queen. White Rabbit A Ball at the Palace Alice, Queen. White Rabbit. Knave, Caterpillar ACT II SCENE l:THE MAD HATTER'S GARDEN Four O'Cloclc Tea. ...............................................Mad Hatter & Dormouse Soon You'll See The Sun Alice, Caterpillar, Knave The Trial The Company SCENE 2:A ROOM IN ALICE'S HOUSE Watch.es (reprise) .................................................Alice Finale The Company ., THE UGHTS COME UP DOWNSTAGE AND WE SEE AUCE SEATED AT A DRESSING TABLE. TIIE MIRROR ON THE TABLE IS SHAPED VERY MUCH LIKE A LARGE HAND-MIRROR. AUCE IS A YOUNG GrRL SOMEWHERE BElWEEN THE AGES OF TEN AND TWELVE YEARS OLD AND IS DRESSED IN CLOTHES APPROPRIATE FOR A YOUNG GIRL UVING IN THE GENTRIDED ENGUSH COUNTRYSIDE OF THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY. UPSTAGE IN THE SHADOWS THERE ARE SHAPES WE CANNOT MAKE OUT Bur WllL LATER BE SEEN AS 1HE •MARKERS* OF •woNDERLAND.• WE HEAR VOICES UGHTLY CAlLING Our TO AUCE. SHE IS NOT SURE WHAT SHE IS HEARING. OFFSTAGE VOICE (singing) A1ice....Aiice AUCE What? Who called? OFFSTAGE VOICE (singing) THAT'S THE WAY, YOU SEE NEVER TO MISS•••• AUCE. -

Legends in a Snowfall

LEGENDS IN A SNOWFALL By Claudia Haas Performance Rights It is an infringement of the federal copyright law to copy or reproduce this script in any manner or to perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co., Inc. Call the publisher for additional scripts and further licensing information. The author’s name must appear on all programs and advertising with the notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Company.” PUBLISHED BY ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING COMPANY www.histage.com © 1999 by Claudia Haas Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing http://www.histage.com/playdetails.asp?PID=1605 Legends in a Snowfall - 2 - STORY OF THE PLAY Winter tales from around the world come together to celebrate the joys and wonders of this dark and cold season. Ellisandra, a weather spirit who hopes to become Frost Queen, takes Faith, a frazzled mother, on a journey of imagination. They first meet the Snow Maiden, a beautiful woman who can only live during winter, in a legend from Russia. Tempesta, a stormy weather spirit who also seeks the title of Frost Queen, follows with her own Native American tale from Minnesota. It’s about a young poet at odds with a warrior lifestyle and his encounter with a Great White Bear. The tales are threaded together with an Eskimo story about the Northern Lights. The characters are a wonderful mix of humans, spirits, mischievous snowflakes and sparkling northern lights. Suggested music adds a grace note to creating the perfect winter solstice program. This play promises winter enchantment for all. -

00:00:02 Jesse Thorn Host Welcome to the Judge John Hodgman Podcast

00:00:00 Sound Effect Transition [Three gavel bangs.] 00:00:02 Jesse Thorn Host Welcome to the Judge John Hodgman podcast. I'm Bailiff Jesse Thorn. This week: "Neverlandmark Case." Jessie files suit against her husband Ryan. During a past relationship, Ryan's ex-girlfriend made him a Peter Pan–themed painting, and he still has it. Jessie wants to get rid of the painting, but Ryan can't bring himself to do it. Who's right? Who's wrong? Only one can decide. 00:00:26 Sound Effect Sound Effect [As Jesse speaks below: Door opens, chairs scrape on the floor, footsteps.] 00:00:27 Jesse Host Please rise as Judge John Hodgman enters the courtroom and presents an obscure cultural reference. 00:00:32 Sound Effect Sound Effect [Door shuts.] 00:00:33 John Host We all know Peter Pan. Peter Pan is the story of a young woman Hodgman who gets ensnared in a relationship with an adulterous narcissist, a guy who literally commands his partner to be his mother, but it's okay, 'cause the young woman thinks her love can fix him! But the narcissist cannot be fixed! And he eventually leaves Wendy for a younger woman, who happens to be Wendy's own daughter! Bailiff Jesse Thorn, swear them in. 00:00:59 Jesse Host Jesse, Ryan, please rise and raise your right hands. 00:01:00 Sound Effect Sound Effect [Chairs scrape.] 00:01:02 Jesse Host Do you swear to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God or whatever? 00:01:07 Jessie Guest I do. -

Walt Disneys Alice in Wonderland Free

FREE WALT DISNEYS ALICE IN WONDERLAND PDF Rh Disney | 24 pages | 05 Jan 2010 | Random House USA Inc | 9780736426701 | English | New York, United States Alice in Wonderland | Disney Movies Published by Simon and Schuster. Seller Rating:. About this Item: Simon and Schuster. Condition: Fair. First edition copy. Reading copy only. Spine Walt Disneys Alice in Wonderland. Seller Inventory Q12C More information about this seller Contact this seller 1. Condition: Near Fine. First Thus. Illustrated Glazed Board Covers; Covers are clean and bright; Walt Disneys Alice in Wonderland right front corner is rubbed and spine panel has a small chip at gutter edge near bottom; Pictorial endpapers; Fixed front endpaper has previous owner's name in upper left corner; Book interior is clean and tight and unmarked; 4to; 96 pages. Seller Inventory More information about this seller Contact this seller 2. Pictorial Cover. Condition: Poor. No Jacket. The Walt Disney Studio illustrator. Color and three color illust. Pages yellowed. Hairline tears on pages. Pen markings on title page. Owners name inscribed on inside of front cover. Spine worn. Covers worn around edges. Corners of covers bent. Seller Inventory B. More information about this seller Contact this seller 3. Published by Disney Enterprises, US Condition: Fine. More information about this seller Contact this seller 4. Cloth Hardbound. Condition: Near Very Good. Walt Disney Studios illustrator. First Edition. Unpaginated Interior is clean, bright and Walt Disneys Alice in Wonderland Small scribble on front cover Wear at corners of cover Small chips at base of spine. More information about this seller Contact this seller 5. -

Through the Mirror Free

FREE THROUGH THE MIRROR PDF G. M. Berrow | 224 pages | 02 Oct 2014 | Hachette Children's Group | 9781408336601 | English | London, United Kingdom Through the Looking-Glass - Wikipedia From " Veronica Mars " to Rebecca take a look back at the career of Armie Hammer on and off the screen. See the full gallery. Biographical documentary of Lee Miller aka Elizabeth Miller,her early years in USA under her father's influence, later became a model turned artist and celebrated photographer, including her photojournalism during WWII, and her second marriage to British surrealism painter Roland Penrose postwar. Film is told through interviews with Miller's son, Antony Penrose. The various phases of Lee Miller's life and works are accounted and revealed by writer-director Sylvain Roumette, with the collaboration of Lee's son, Antony Penrose, Lee's Through the Mirror wartime journalist friend David Scherman, and Patsy I. Murray whom Lee brought in as the 'second mother' to Through the Mirror. Early in the film: "I longed to be loved, just once, somewhat purely and chastely, to have youth and innocence so. The film provided personal insights and fond reminiscences of their times with Lee from Antony, Scherman and Murray. And by the end, we can tell that Antony Penrose, with the help and understanding of Scherman, is resolved with his differences towards his mother. Anyone who appreciates photography, art, surrealism, Man Ray, woman influences, or simply a worthwhile documentary - do check out Through the Mirror film available on DVD. The "Portfolio" option gives a photo synopsis of the eight stages of Lee Miller's life. -

Open Gencarelli Alicia Peterpan.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH “TO LIVE WOULD BE AN AWFULLY BIG ADVENTURE”: MASCULINITY IN J.M. BARRIE’S PETER PAN AND ITS CINEMATIC ADAPTATIONS ALICIA GENCARELLI SUMMER 2017 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Garrett Sullivan Liberal Arts Research Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Marcy North English Honors Advisor Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This thesis discusses the representation of masculinity in J.M. Barrie’s novel, Peter Pan, as well as in two of its cinematic adaptations: Disney’s Peter Pan and P.J. Hogan’s Peter Pan. In particular, I consider the question: What exactly keeps Peter from growing up and becoming a man? Furthermore, I examine the cultural ideals of masculinity contemporary to each work, and consider how they affected the work’s illustration of masculinity. Then, drawing upon adaptation theory, I argue that with each adaptation comes a slightly variant image of masculinity, producing new meanings within the overall narrative of Peter Pan. This discovery provides insight into the continued relevance of Peter Pan in Western society, and subsequently, how a Victorian children’s adventure fiction is adapted to reflect contemporary ideologies and values. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... iii Introduction -

SINGING SYLLABUS Qualification Specifications for Graded Exams 2018–2022

BRITTEN GERSHWIN POULENC SINGING FAURÉ SYLLABUS QUILTER THIMAN Qualification specifications for graded exams 2018–2022 MENKEN PURCELL SKEMPTON BOULANGER MENDELSSOHN BERNSTEIN CRAWLEY SCHUBERT SONDHEIM WARLOCK ROREM DRING BART ROE KEEP UP TO DATE Please check trinitycollege.com/singing to make sure you are using the current version of the syllabus and for the latest information about our Singing exams. DIGITAL ASSESSMENT: DIGITAL GRADES AND DIPLOMAS To provide even more choice and flexibility in how Trinity’s regulated qualifications can be achieved, digital assessment is available for all our classical, jazz and Rock & Pop graded exams, as well as for ATCL and LTCL music performance diplomas. This enables candidates to record their exam at a place and time of their choice and then submit the video recording via our online platform to be assessed by our expert examiners. The exams have the same academic rigour as our face-to-face exams, and candidates gain full recognition for their achievements, with the same certificate and UCAS points awarded as for the face-to-face exams. Find out more at trinitycollege.com/dgd SINGING SYLLABUS Qualification specifications for graded exams 2018–2022 Charity number England & Wales: 1014792 Charity number Scotland: SC049143 Patron: HRH The Duke of Kent KG trinitycollege.com Copyright © 2017 Trinity College London Published by Trinity College London Online edition, June 2021 1 Header Left Contents 3 / Welcome 4 / Introduction to Trinity’s graded music exams 7 / Learning outcomes and assessment criteria 8 / About the exam 10 / Exam guidance: Songs 12 / Exam guidance: Technical work 13 / Exam guidance: Supporting tests 19 / Exam guidance: Marking 24 / Initial 27 / Grade 1 31 / Grade 2 35 / Grade 3 40 / Grade 4 45 / Grade 5 51 / Grade 6 60 / Grade 7 68 / Grade 8 78 / Policies 79 / Publishers 80 / Trinity publications 80 / Join us online… Trinity accepts entries for its exams on the condition that candidates conform to the requirements of the appropriate syllabus. -

WOO HOO! Time to Par-Tay!!!

A Newsletter Exclusively for Disney Enthusiasts VOLUME 19 NO. 2 SUMMER, 2010 WOO HOO! Time to Par-tay!!! There will also be a selection of limited edition merchandise This year is the 55th anniversary of Disneyland Resort, and D23 available for purchase at the event. is celebrating this milestone year with the premiere of Destina- tion D: Disneyland ’55, a brand-new, two-day event that illumi- Here is the current lineup for Destination D: Disneyland ’55 nates the fascinating history behind Disney’s flagship park. FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 2010 Destination D: Disneyland ’55 will take D23 Members on a mesmerizing journey through Mickey Mouse Club 55th Anniversary the design, creation, debut and magical his- Join original Mouseketeers including Sharon Baird, tory of the world’s first Disney theme park. Doreen Tracey, Bobby Burgess, Karen Pendleton, The event will offer two full days of special Sherry Van Meter (Alberoni), Tommy Cole, Cubby presentations, panels, screenings and guest O’Brien and Mary Geoff (Espinosa) for a magi- speakers that give fans an inside view of cal walk down memory lane as they recall their this fascinating era in Disney history and favorite behind-the-scenes stories from the classic let them meet and talk with key figures in Disneyland attraction Mickey Mouse Club Circus. Disneyland’s history. Future Destination D events will explore other important aspects Weird Disney of Disney’s amazing creative legacy. Follow- From the startling visuals of the 1930s Fanchon ing its premiere in September, Destination & Marco “Mickey Mouse Idea” vaudeville shows D will alternate annually with the enor- to Disneyland’s “Kap the Kaiser Aluminum Pig” mously popular D23 Expo. -

Anido FILM1 30E

FILM 1/30e No.1 The Exhibition of Mr. Mukuo Takamura Mukuo at his Studio (Photo:T.Namiki) The retrospective exhibition of Mr. Takamura Mukuo, who had passed away 3 year ago, was held at the Museum in Machida. This April under the auspices of his family. He the leading person in background painters of Japanese animation field produced numerous wonderful works. Though they offered free- entrance, it was rich in content. There were more than 100 background paintings drawn by him, from his early works such as "Marco", "Gosch, the Cellist", "The Dagger of Kamui", to his posthumous works like "Sailor Moon". They gave us the full picture of his career as a background designer for 30 years. They were enough to remind almost 600 fans, who visited exhibition at his talent. Mr. Mukuo first helped ANIDO directlywith the article on "Marco" in FILM 1/24, No. 23. The background of "Gosch, the Cellist" most of which were was so great that I can never forget that drawn by him. During its production, I worked as an animator. Even after that, I took a part in advertisement. He helped us a lot, like making a guest appearance when we held screenings, joining the discussion for the animation magazine, drawing background of the pictures for badges and other goods, and so on. It's very sad to say Mr. Mukuo had already passed away. But I believe that we, people in Japanese animation field, will never forget his earnest attitude toward creation. ANIDO is now planning to publish the book of his wonderful works. -

Manor Primary School PE Year 1: Active Play – Invasion Games

Manor Primary School PE Year 1: Active play – invasion games Overview of the Learning: In this unit of learning children will be introduced to a multi-skills approach to learning through activities that are fundamentals of movement. This approach focuses on the development of movement, balance and co- ordination which link to the long term athlete development framework. The approach also helps children develop the five multi-abilities of creative, cognitive, social, physical and personal development. Developing competence in fundamental movement skills leads to competence in more complex sports skills. E.g) an overarm throw involves co-ordinating body parts which when mastered aids the development of throwing in cricket and rounders, the javelin throw, tennis serve and the netball shoulder pass. Core Aims Pupils should be taught to acquire and develop skills by: . develop competence to excel in a broad range of physical activities . explore basic skills, actions and ideas with increasing understanding . becoming physically active for sustained periods of time . remember and repeat simple skills and actions with increasing control and coordination. engage in competitive sports and activities . lead healthy, active lives. Pupils should be taught to select and apply skills, tactics and compositional ideas: . reflect on and evaluate evidence when making personal choices or bringing about improvements in . explore how to choose and apply skills and actions in sequence and in combination performance and behaviour . vary the way they perform skills by using simple tactics and movement phrases . generate and implement ideas, plans and strategies, exploring alternatives . apply rules and conventions for different activities. move with ease, poise, stability and control in a range of physical contexts Evaluating and improving performance. -

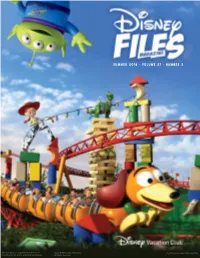

Summer 2018 • Volume 27 • Number 2

Summer 2018 • Volume 27 • Number 2 Slinky® Dog is a registered trademark of Jenga® Pokonobe Associates. Toy Story characters ©Disney/Pixar Poof-Slinky, Inc. and is used with permission. All rights reserved. WeLcOmE HoMe Leaving a Disney Store stock room with a Buzz Lightyear doll in 1995 was like jumping into a shark tank with a wounded seal.* The underestimated success of a computer-animated film from an upstart studio had turned plastic space rangers into the hottest commodities since kids were born in a cabbage patch, and Disney Store Cast Members found themselves on the front line of a conflict between scarce supply and overwhelming demand. One moment, you think you’re about to make a kid’s Christmas dream come true. The next, gift givers become credit card-wielding wildebeest…and you’re the cliffhanging Mufasa. I was one of those battle-scarred, cardigan-clad Cast Members that holiday season, doing my time at a suburban-Atlanta mall where I developed a nervous tick that still flares up when I smell a food court, see an astronaut or hear the voice of Tim Allen. While the supply of Buzz Lightyear toys has changed considerably over these past 20-plus years, the demand for all things Toy Story remains as strong as a procrastinator’s grip on Christmas Eve. Today, with Toy Story now a trilogy and a fourth film in production, Andy’s toys continue to find new homes at Disney Parks around the world, including new Toy Story-themed lands at Disney’s Hollywood Studios (pages 3-4) and Shanghai Disneyland (page 22).