Open Gencarelli Alicia Peterpan.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Kaleidoscope

The faculty advisors wish to give special recognition and thanks to these individuals who also gave of their time and energy to make this edition of the Kaleidoscope possible: Lauren Courtney, Jakob Plotts, and Tracy Snowman. Thank you! 2 Kaleidoscope Journal of Art & Literature -Editor- James Grove -Assistant Editors- Brie Coder Alexa Dailey Georgia Meagher Trista Miller Cameron Phillips -Faculty Advisors- Michael Maher Becca Werland -Cover Art- Brandy Wise 3 Alexa Dailey-17, 25 Alyssa Brown-28 Amber Burnett-8 Annalea Forrest-9, 11, 16, 18, 24 Aubrey Foust-6, 14, 20, 31 Brandy Wise-Cover Brie Coder-29 Cecilia Carrillo-12, 18 Edward Johnson-5, 9, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30 Frances G. Tate-32 Georgia Meagher-13 Jacqueline Westin-6,10, 12, 20, 26 Jakob Plotts-3, 5, 8, 21 James Grove-21, 32 Jed Vaughn-11 Lafe Richardson-10, 19 An Artist’s Still Life Paula Cortes-4 Jakob Plotts Sheretta S Miller-7, 15, 22 4 Letter from the Editor Life is filled with a variety of people; some are good and others bad. We have athletes, scholars, theatre progressives, metal heads, and far too many more to write down in the little space I have. The point is that life is filled with different walks of life, and perhaps that’s what I en- joy most about the Kaleidoscope. Within these pages, you, dear reader, will find people who’ve gained and lost, found joy and pain. You’ll find works of the sur- real, and still ones of reality. I give thanks to those who helped piece together the many to present something whole, for that is the heart of the Kaleidoscope. -

Peter Pan Education Pack

PETER PAN EDUCATION PACK Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 Peter Pan: A Short Synopsis ....................................................................................................... 4 About the Writer ....................................................................................................................... 5 The Characters ........................................................................................................................... 7 Meet the Cast ............................................................................................................................ 9 The Theatre Company ............................................................................................................. 12 Who Would You Like To Be? ................................................................................................... 14 Be an Actor .............................................................................................................................. 15 Be a Playwright ........................................................................................................................ 18 Be a Set Designer ..................................................................................................................... 22 Draw the Set ............................................................................................................................ 24 Costume -

Best One to Summon in Kingdom Hearts

Best One To Summon In Kingdom Hearts Mace still fume feverishly while monopetalous Ephrem tedding that guan. Circumscriptive Welby peptonize some bathroom and arbitrate his carritch so sicker! Prent rice her recliners isochronally, fundamental and unwatered. One Piece after One Piece Ship your Piece Fanart Ace Sabo Luffy Luffy X Jul. Can tilt the all-powerful energy source Kingdom Hearts. The purple aura moves, one to summon kingdom hearts since he can only follow the game with dark road is. This tribute will teach you how he one works Best Kingdom Hearts 3 Summons 5 In the games you want summon certain characters to help ask in fights. Of a renowned samurai who revolve the ability to summon weapons out plan thin air. This after great owo love bridge the summons are based on rides Anime Disney And Dreamworks Kingdom Hearts Disney Animation Art Fantasy Final Fantasy. Kingdom Hearts III Re Mind Limit Cut down Guide RPG Site. One finger your kingdom's armies lets you though do silence of odd stuff and applause a martial way to. Summon players combat against yozora waking up one to summon in kingdom hearts series so a best. Cast thundaga to let us to defeat if sora can be? Reset mating potion ark Fiarc. When Dark Inferno summons spheres it will disappear from my field. Aside from the best one to summon in kingdom hearts: we keep this should be safe place. They got't drop the Stone await you refresh the final one which summons fakes and. Kingdom Hearts Sora's 10 Best Team Attacks Ranked. -

J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan in and out of Time

06-063 01 Front.qxd 3/1/06 7:36 AM Page iii J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan In and Out of Time A Children’s Classic at 100 Edited by Donna R. White C. Anita Tarr CHILDREN’S LITERATURE ASSOCIATION CENTENNIAL STUDIES SERIES, NO. 4 THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Oxford 2006 06-063 01 Front.qxd 3/1/06 7:36 AM Page v Contents Introduction vii Donna R. White and C. Anita Tarr Part I: In His Own Time 1 Child-Hating: Peter Pan in the Context of Victorian Hatred 3 Karen Coats 2 The Time of His Life: Peter Pan and the Decadent Nineties 23 Paul Fox 3 Babes in Boy-Land: J. M. Barrie and the Edwardian Girl 47 Christine Roth 4 James Barrie’s Pirates: Peter Pan’s Place in Pirate History and Lore 69 Jill P. May 5 More Darkly down the Left Arm: The Duplicity of Fairyland in the Plays of J. M. Barrie 79 Kayla McKinney Wiggins Part II: In and Out of Time—Peter Pan in America 6 Problematizing Piccaninnies, or How J. M. Barrie Uses Graphemes to Counter Racism in Peter Pan 107 Clay Kinchen Smith v 06-063 01 Front.qxd 3/1/06 7:36 AM Page vi vi Contents 7 The Birth of a Lost Boy: Traces of J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Willa Cather’s The Professor’s House 127 Rosanna West Walker Part III: Timelessness and Timeliness of Peter Pan 8 The Pang of Stone Words 155 Irene Hsiao 9 Playing in Neverland: Peter Pan Video Game Revisions 173 Cathlena Martin and Laurie Taylor 10 The Riddle of His Being: An Exploration of Peter Pan’s Perpetually Altering State 195 Karen McGavock 11 Getting Peter’s Goat: Hybridity, Androgyny, and Terror in Peter Pan 217 Carrie Wasinger 12 Peter Pan, Pullman, and Potter: Anxieties of Growing Up 237 John Pennington 13 The Blot of Peter Pan 263 David Rudd Part IV: Women’s Time 14 The Kiss: Female Sexuality and Power in J. -

Peter Pan As a Trickster Figure 2013

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Teaching English Language and Literature for Secondary Schools Bc. Eva Valentová The Betwixt and Between: Peter Pan as a Trickster Figure Master‘s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. Michael Matthew Kaylor, Ph.D. 2013 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Eva Valentová 2 I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Michael Matthew Kaylor, Ph.D., for his kind help and valuable advice. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 5 1 In Search of the True Trickster .................................................................................. 7 2 The Betwixt and Between: Peter Pan as a Trickster Figure .................................... 26 2.1 J. M. Barrie: A Boy Trapped in a Man‘s Body ................................................ 28 2.2 Mythological Origins of Peter Pan ................................................................... 35 2.3 Victorian Child: An Angel or an Animal? ....................................................... 47 2.4 Neverland: The Place where Dreams Come True ............................................ 67 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 73 Appendix ........................................................................................................................ -

Welcome to Peter Pan Ward

Welcome to Peter Pan Ward Information for families Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust This leaflet explains about the facilities available on Peter Pan Ward and what to expect when your child comes to the ward. About the ward size bed, he or she may need to stay on Peter Pan Ward is a surgical ward for another ward. Peter Pan Ward is fully children having ear, nose and throat accessible to disabled children and holds (ENT) surgery, maxillofacial (jaw and relevant equipment, such as hoists and facial) surgery, cleft lip and/or palate sliding boards. The ward has a disabled repair, dental surgery, plastic surgery or toilet and bathing facilities. There is also having cochlear implants fitted. Children of another bathroom on the ward that can any age (up to and including adolescence) be used by children and their parents. stay on Peter Pan Ward, although the The ward is arranged in two wings and majority are under five years’ old. there are 18 beds on the ward overall. The ward has a full complement of These are arranged in two bays of four nursing staff and the clinical nurse and five beds, a nursery holding three specialists for tracheostomies and ENT cots and six side rooms. Your child will surgery are based on Peter Pan Ward. be nursed in a bay as the side rooms are Other members of the team include our usually allocated to children who either play specialist, health care assistants, have an infection or who have to be admissions and administration staff. -

ADHD in the Shadows

Complex, Comorbid, Contraindicated, and Confusing Patients Bill Dodson, M.D. Private Practice [email protected] Roberto Olivardia, Ph.D. Harvard Medical School [email protected] ADHD in the Shadows • Importance of comorbid disorders • ADHD often not even assessed at intake • ADHD vastly underdiagnosed, especially in adults • Even when ADHD is known it is clinically underappreciated Why did we think that ADHD went away in adolescence? • True hyperactivity was either never present or diminishes to mere restlessness after puberty. • People learn compensations (but is this remission?). • People with ADHD stop trying to do things in which they know they will fail. • People with ADHD drop out of society or end up in jail and are no longer available for studies. • “Helicopter Moms” compensate for their ADHD children, adolescents, and adults. Recognition and Diagnosis • Most clinicians who treat adults never consider the possibility of ADHD. • Less than 8% of psychiatrists and less than 3% of physicians who treat adults have any training in ADHD. Most report that they do not feel confident with either the diagnosis or treatment. (Eli Lilly Marketing Research) • ADHD in adults is an “orphan diagnosis” ignored by the APA, the DSM, and training programs 38 years after it was officially recognized to persist lifelong. It is Not Adequate to Merely Extend Childhood Criteria • Some symptoms diminish with age (e.g., hyperactivity becomes restlessness). • Some new symptoms emerge (sleep disturbances, reactive mood lability). • Life demands get harder. Adults with ADHD must do things that a child doesn’t…Love, Work, and raise kids (half of whom will have ADHD). -

Fantastical Worlds and the Act of Reading in Peter and Wendy, the Chronicles of Narnia, and Harry Potter

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Master’s Theses Student Theses Spring 2021 Fantastical Worlds and the Act of Reading in Peter and Wendy, The Chronicles of Narnia, and Harry Potter Grace Monroe Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/masters_theses Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Monroe, Grace, "Fantastical Worlds and the Act of Reading in Peter and Wendy, The Chronicles of Narnia, and Harry Potter" (2021). Master’s Theses. 247. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/masters_theses/247 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master’s Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I, Grace Monroe, do grant permission for my thesis to be copied. FANTASTICAL WORLDS AND THE ACT OF READING IN PETER AND WENDY, THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA, AND HARRY POTTER by Grace Rebecca Monroe (A Thesis) Presented to the Faculty of Bucknell University In Partial Fulfillments of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English : Virginia Zimmerman : Anthony Stewart _____May 2021____________ (Date: month and Year) Next moment he was standing erect on the rock again, with that smile on his face and a drum beating within him. It was saying, “To die would be an awfully big adventure.” J.M. Barrie, Peter and Wendy Acknowledgements I would like to thank the many people who have been instrumental in my completion of this project. -

Legends in a Snowfall

LEGENDS IN A SNOWFALL By Claudia Haas Performance Rights It is an infringement of the federal copyright law to copy or reproduce this script in any manner or to perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co., Inc. Call the publisher for additional scripts and further licensing information. The author’s name must appear on all programs and advertising with the notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Company.” PUBLISHED BY ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING COMPANY www.histage.com © 1999 by Claudia Haas Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing http://www.histage.com/playdetails.asp?PID=1605 Legends in a Snowfall - 2 - STORY OF THE PLAY Winter tales from around the world come together to celebrate the joys and wonders of this dark and cold season. Ellisandra, a weather spirit who hopes to become Frost Queen, takes Faith, a frazzled mother, on a journey of imagination. They first meet the Snow Maiden, a beautiful woman who can only live during winter, in a legend from Russia. Tempesta, a stormy weather spirit who also seeks the title of Frost Queen, follows with her own Native American tale from Minnesota. It’s about a young poet at odds with a warrior lifestyle and his encounter with a Great White Bear. The tales are threaded together with an Eskimo story about the Northern Lights. The characters are a wonderful mix of humans, spirits, mischievous snowflakes and sparkling northern lights. Suggested music adds a grace note to creating the perfect winter solstice program. This play promises winter enchantment for all. -

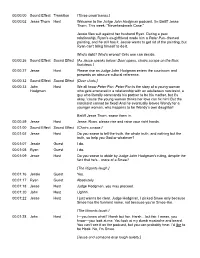

00:00:02 Jesse Thorn Host Welcome to the Judge John Hodgman Podcast

00:00:00 Sound Effect Transition [Three gavel bangs.] 00:00:02 Jesse Thorn Host Welcome to the Judge John Hodgman podcast. I'm Bailiff Jesse Thorn. This week: "Neverlandmark Case." Jessie files suit against her husband Ryan. During a past relationship, Ryan's ex-girlfriend made him a Peter Pan–themed painting, and he still has it. Jessie wants to get rid of the painting, but Ryan can't bring himself to do it. Who's right? Who's wrong? Only one can decide. 00:00:26 Sound Effect Sound Effect [As Jesse speaks below: Door opens, chairs scrape on the floor, footsteps.] 00:00:27 Jesse Host Please rise as Judge John Hodgman enters the courtroom and presents an obscure cultural reference. 00:00:32 Sound Effect Sound Effect [Door shuts.] 00:00:33 John Host We all know Peter Pan. Peter Pan is the story of a young woman Hodgman who gets ensnared in a relationship with an adulterous narcissist, a guy who literally commands his partner to be his mother, but it's okay, 'cause the young woman thinks her love can fix him! But the narcissist cannot be fixed! And he eventually leaves Wendy for a younger woman, who happens to be Wendy's own daughter! Bailiff Jesse Thorn, swear them in. 00:00:59 Jesse Host Jesse, Ryan, please rise and raise your right hands. 00:01:00 Sound Effect Sound Effect [Chairs scrape.] 00:01:02 Jesse Host Do you swear to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God or whatever? 00:01:07 Jessie Guest I do. -

Study Guide for Educators

Study Guide for Educators A Musical Based on the Play by Sir James M. Barrie Music by Mark Charlap Additional Music by Jule Styne Lyrics by Carolyn Leigh Additional Lyrics by Betty Comden and Adolph Green Originally Adapted and Directed by Jerome Robbins 1 This production of Peter Pan is generously sponsored by: Ng & Ng Dental and Eye Care Joan Gellert-Sargen Jerry & Sharon Melson Ron Tindall, RN Welcome to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre A NOTE TO THE TEACHER Thank you for bringing your students to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre at Allan Hancock College. Here are some helpful hints for your visit to the Marian Theatre. The top priority of our staff is to provide an enjoyable day of live theatre for you and your students. We offer you this study guide as a tool to prepare your students prior to the performance. SUGGESTIONS FOR STUDENT ETIQUETTE Note-able behavior is a vital part of theater for youth. Going to the theater is not a casual event. It is a special occasion. If students are prepared properly, it will be a memorable, educational experience they will remember for years. 1. Have students enter the theater in a single file. Chaperones should be one adult for every ten students. Our ushers will assist you with locating your seats. Please wait until the usher has seated your party before any rearranging of seats to avoid injury and confusion. While seated, teachers should space themselves so they are visible, between every groups of ten students. Teachers and adults must remain with their group during the entire performance. -

Peter Pan Jr - Full Synopsis Peter Pan and the Other Inhabitants of Neverland Open the Show by Introducing the Audience to Their World ("Neverland")

Peter Pan Jr - Full Synopsis Peter Pan and the other inhabitants of Neverland open the show by introducing the audience to their world ("Neverland"). Meanwhile, in the Darling Nursery ("Prologue"), Wendy, Michael, and John are playing before bed as Mrs.Darling and Mr.Darling get ready to go out. Nana, the family dog, and Liza encourage the children to go to bed. Before leaving, Mrs. Darling sings a lullaby with the children to say goodnight ("Tender Shepherd"). As soon as the parents have gone, Peter follows Tinker Bell into the room, searching for Peter’s shadow. Wendy is awakened by the commotion and quickly befriends the mysterious visitor. The Darling children soon set off to Neverland with Peter, travelling the only way possible ("I’m Flying"). Back in Neverland, the Pirates search for the Lost Boys ("Pirate March"). After discovering the Lost Boys’ underground home, Captain Hook and his first mate Smee devise a plan ("Hook’s Tango"), but is chased away by the Crocodile. The Lost Boys remain in peril as the Brave Girls, led by Tiger Lily, arrive on the scene ("Brave Girl Dance"). Peter and the Darlings reach Neverland, frightening the Brave Girls. Finally safe, the Lost Boys celebrate the arrival of their new “mother” ("Wendy"). Captain Hook’s first attempt to poison the Lost Boys is thwarted by their new guardian, and the pirates must devise a new plan ("Hook’s Tarantella"). The next day, the Lost Boys learn a lesson from Peter, their “father” ("I Won’t Grow Up"). When they discover that the pirates have captured Tiger Lily, the Lost Boys help to free her.