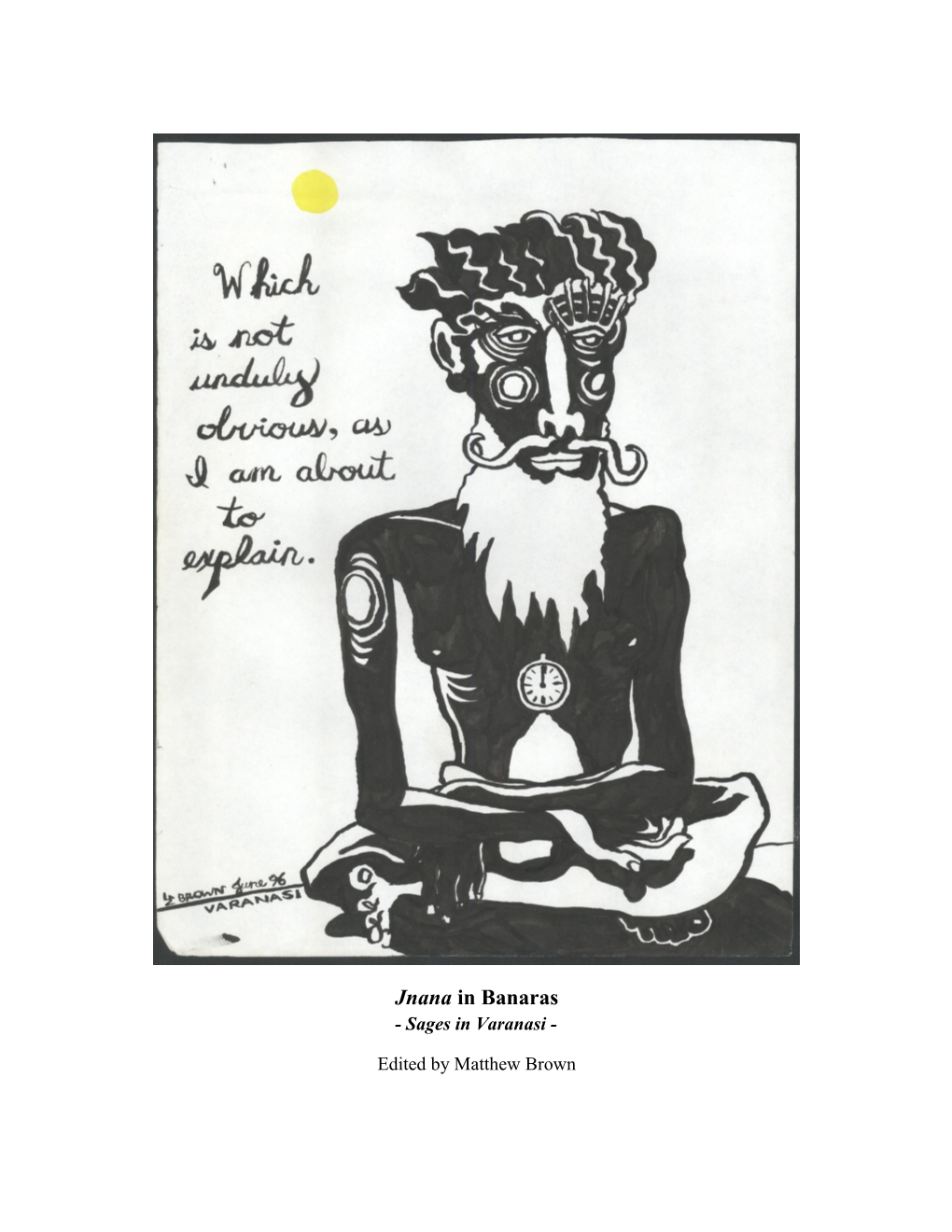

Jnana in Banaras - Sages in Varanasi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GANDHI a Pictorial Biography

GANDHI a pictorial biography Written by: B. R. Nanda First Published : January 1972 Published by: The Director, Publications Division Ministry of Information and Broadcasting Government of India Patiala House, New Delhi 110 001 Website: www.publicationsdivision.nic.in GANDHI a pictorial biography This is the first pictorial biography of Gandhi in which the narrative-concise, readable and incisive is illustrated with contemporary photographs and facsimiles of letters, newspaper reports and cartoons, adding up to a fascinating flash-back on the life of Mahatma Gandhi and the struggle for Indian freedom led by him. There is a skilful matching in this book of text and illustrations, of description and analysis and of concrete detail and large perspective. This pictorial biography will revive many memories in those who have lived through the Gandhian era; it should also be of interest to the post- independence generation. www.mkgandhi.org Page 2 GANDHI a pictorial biography Sevagram ashram near Wardha in Maharashtra founded by Gandhiji in 1936. In January 1948, before three pistol shots put an end to his life, Gandhi had been on the political stage for more than fifty years. He had inspired two generations of India, patriots, shaken an empire and sparked off a revolution which was to change the face of Africa and Asia. To millions of his own people, he was the Mahatma- the great soul- whose sacred glimpse was a reward in itself. By the end of 1947 he had lived down much of the suspicion, ridicule and opposition which he had to face, when he first raised the banner of revolt against racial exclusiveness and imperial domination. -

How Chinmaya Mission Trains Leaders

e d u cati o N How Chinmaya Mission Trains Leaders The two-year Vedanta course at Sandeepany Sadhanalaya in Mumbai demands rigorous personal discipline, deep devotion and intense scriptural study Chinmaya Mission’s training program is practice. Here the acharyas (teachers) of no ordinary course of study. It is a 24/7 Chinmaya Mission are trained in a two-year commitment of body, mind and soul to an program which begins and ends on Ganesha immersive spiritual adventure. A recent Chathurti. A year later, a new course begins. graduate, Acharya Vivek, recounts his I was honored to join the 13th course, which extraordinary experience. commenced in 2005. I was born and raised in Niagara Falls, By Acharya Vivek, Canada, to devotees of Swami Tejomayanan- Chinmaya Mission da, the current head of Chinmaya Mission. I Niagara, Canada pursued all that any young Canadian would: ome great men try to improve the higher education, travelling, fancy posses- world by changing the outer settings sions. Like everyone else, I followed these of economic and societal conditions. pursuits for the sake of happiness. And like S A few greater men try to change the everyone else, happiness eluded me—time processes and the vision of the masses. The and time again. This was an intensely tiring very greatest achieve a complete and last- period of my life. ing transformation, one individual at a time. Relief came from a most unexpected That was Swami Chinmayananda’s vision source. I had learned that Swami Tejoma- when he created Sandeepany Sadhanalaya yananda himself was going to be the Resi- in 1963. -

108 Names of Anandamayi Ma

108 Names of Shrī Ānandamayī Ma 1) Shrī Mātre Supreme Mother encompassing both female and male forms 2) Hridayavasinī She who resides in the heart 3) Sanātanī The Eternal one 4) Ānandamayī Bliss permeated 5) Bhuvana Ujjāla One who illuminates the universe 6) Jananī She who gives birth 7) Shūddhya Pure 8) Nirmala Without karmic limitation 9) Punyavistārinī She who spreads virtue all around 10) Rajrajeshwari Queen of queens 11) Swāhā The essence of devotional offering 12) Swadha ̄ The essence of offerings to the ancestors 13) Gourī Fair complexioned 14) Pranavarūpinī The manifest form of OM 15) Saumya Pleasing 16) Saumyatāra Pleasing to a higher degree 17) Satya Supreme Reality 18) Manohara One who steals the mind 19) Pūrna Fullness itself 20) Parātpara Superior to the superior 21) Ravishashi Kundala Wearing the Sun and Moon as Her earrings 22) Mahāvyoma Kuntala Having the vast expanse of the sky as Her hair 23) Viswarūpinī Assuming all forms in the universe 24) Aishwarya Bhātima Splendor of riches 25) Mādhurya Pratima ̄ Image of sweetness 26) Mahimā Mandita Possessing the greatness/divine power of Yogis 27) Rāma Avatar of Lord Vishnu 28) Manorama Pleasing (to) the mind 29) Shānti Peace itself 30) Shānta Peaceful; composed 31) Kshamā Forgiveness itself 32) Sarva Devamayī Full of all gods 33) Sarva Devimayī Full of all goddesses 34) Sukhadāyini One who gives happiness 35) Varadāyini One who gives boons 36) Bhaktidāyini One who provides devotional mentality 37) Jñānadāyini One who gives wisdom 38) Kaivalya Dāyini One who gives emancipation -

The Inner Light: the Beatles, India, Gurus, and the Legacy

The Inner Light: The Beatles, India, Gurus, and the Legacy John Covach Institute for Popular Music, University of Rochester Arthur Satz Department of Music Eastman School of Music Main Points The Beatles’ “road to India” is mostly navigated by George Harrison John Lennon was also enthusiastic, Paul somewhat, Ringo not so much Harrison’s “road to India” can be divided into two kinds of influence: Musical influences—the actual sounds and structures of Indian music Philosophical and spiritual influences—elements that influence lyrics and lifestyle The musical influences begin in April 1965, become focused in fall 1966, and extend to mid 1968 The philosophical influences begin in late 1966 and continue through the rest of Harrison’s life Note: Harrison began using LSD in the spring of 1965 and discontinued in August 1967 Songs by other Beatles, Lennon especially, also reflect Indian influences The Three “Indian” songs of George Harrison “Love You To” recorded April 1966, released on Revolver, August 1966 “Within You Without You” recorded March, April 1967, released on Sgt Pepper, June 1967 “The Inner Light” recorded January, February 1968, released as b-side to “Lady Madonna,” March 1968 Three Aspects of “Indian” characteristics Use of some aspect of Indian philosophy or spirituality in the lyrics Use of Indian musical instruments Use of Indian musical features (rhythmic patterns, drone, texture, melodic elements) Musical Influences Ravi Shankar is principal influence on Harrison, though he does not enter the picture until mid 1966 April 1965: Beatles film restaurant scene for Help! Harrison falls in love with the sitar, buys one cheap Summer 1965: Beatles in LA hear about Shankar from McGuinn, Crosby (meet Elvis, discuss Yogananda) October 1965: “Norwegian Wood” recorded, released in December on Rubber Soul. -

The Rise of Bengali Yoga (Excerpt from Sun, Moon and Earth: the Sacred Relationship of Yoga and Ayurveda)

The Rise of Bengali Yoga (Excerpt from Sun, Moon and Earth: The Sacred Relationship of Yoga and Ayurveda) By Mas Vidal To set the stage for a moment, the state of Bengal is an eastern state of India and is one of the most densely populated regions on the planet. It is home to the Ganges river delta at the confluence of the Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers. Rivers have always been a sacred part of yoga and the Indian lifestyle. The capital of Bengal is Kolkata, which was the center of the Indian independence movement. As yoga began to expand at the turn of the century through the 1950s, as a counter-cultural force opposed to British occupation, the region also struggled against a tremendous set-back, the Great Bengal Famine of 1943- 44, which took an estimated two to three million lives. India battled through this and eventually gained independence in 1947. Bengal managed to become a womb for bhakti yogis and the nectar that would sustain the renaissance of yoga in India and across the globe. Bengali seers like Sri Aurobindo promoted yoga as an integral system, a way of life that cultivated a dynamic relationship between mind, body, and soul. Some of the many styles of yoga that provide this pure synthesis remain extant in India, but only through a few living yoga teachers and lineages. This synthesis may even still exist sporadically in commercial yoga. One of the most influential figures of yoga in the West was Paramahansa Yogananda, who formulated a practical means of integrating ancient themes and techniques for the spiritual growth of people in Western societies, and for Eastern cultures to reestablish their balance between spirituality and the material. -

Modern Indian Political Thought Ii Modern Indian Political Thought Modern Indian Political Thought Text and Context

Modern Indian Political Thought ii Modern Indian Political Thought Modern Indian Political Thought Text and Context Bidyut Chakrabarty Rajendra Kumar Pandey Copyright © Bidyut Chakrabarty and Rajendra Kumar Pandey, 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2009 by SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd B1/I-1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area Mathura Road, New Delhi 110 044, India www.sagepub.in SAGE Publications Inc 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320, USA SAGE Publications Ltd 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP, United Kingdom SAGE Publications Asia-Pacifi c Pte Ltd 33 Pekin Street #02-01 Far East Square Singapore 048763 Published by Vivek Mehra for SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd, typeset in 10/12 pt Palatino by Star Compugraphics Private Limited, Delhi and printed at Chaman Enterprises, New Delhi. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chakrabarty, Bidyut, 1958– Modern Indian political thought: text and context/Bidyut Chakrabarty, Rajendra Kumar Pandey. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Political science—India—Philosophy. 2. Nationalism—India. 3. Self- determination, National—India. 4. Great Britain—Colonies—India. 5. India— Colonisation. 6. India—Politics and government—1919–1947. 7. India— Politics and government—1947– 8. India—Politics and government— 21st century. I. Pandey, Rajendra Kumar. II. Title. JA84.I4C47 320.0954—dc22 2009 2009025084 ISBN: 978-81-321-0225-0 (PB) The SAGE Team: Reema Singhal, Vikas Jain, Sanjeev Kumar Sharma and Trinankur Banerjee To our parents who introduced us to the world of learning vi Modern Indian Political Thought Contents Preface xiii Introduction xv PART I: REVISITING THE TEXTS 1. -

Baba: the Life Breath of Every Soul” Is Piercing Me from Inside

Om Sri Sai Ram SAI BABA - THE LIFE BREATH OF EVERY SOUL -I By Chandur D. Mirchandani PROLOGUE Volumes of literature have been written by various authors to sing the glory of Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba and to prove His Avatarhood, and to make people understand the purpose of His mission for taking this human form. I am only trying to add a few drops in the infinite ocean of His love and pray to Him right from the bottom of my heart to accept this humble offering as a token of my deep dedication and yearning for the touch of His Lotus Feet, and to bless me with an inner view, so that I am able to understand and put into practice His teachings and His commandments. Baba is an avatar of love. He has graciously taken this human form, for the sake of the seekers of the truth. Year after Year, and from one Yuga to another Yuga, the saints and sages had been earnestly praying to the Almighty God to descend from His heavenly abode and take a human form. In answer to their prayers and for the sake of the yearning of His devotees and to bring Dharma back to its prime position, the God out of His love and compassion has obliged. How fortunate we all human beings are, to be alive and living at the time when the Avatar Himself is moving in a human body while we can keep a personal rapport with Him and receive the benefit of His Darshan (Glimpse), Sparshan (Touch) and Sambashan (Speech). -

Sathya Sai Speaks

SATHYA SAI SPEAKS VOLUME - 34 Discourses of BHAGAWAN SRI SATHYA SAI BABA Delivered during 2001 PRASANTHI NILAYAM SRI SATHYA SAI BOOKS & PUBLICATIONS TRUST Prasanthi Nilayam - 515 134 Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh, India Grams: BOOK TRUST STD: 08555 ISD: 91-8555 Phone: 87375. FAX: 8723 © Sri Sathya Sai Books & Publications Trust Prasanthi Nilayam (India) All Rights Reserved The copyright and the rights of translation in any language are reserved by the Publisher. No part, para, passage, text or photo-graph or art work of this book should be reproduced, transmitted or utilised, in original language or by translation, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or by any information, storage or retrieval system, except with and prior permission, in writing from The Convener Sri Sathya Sai Books & Publications Trust, Prasanthi Nilayam, (Andhra Pradesh) India, except for brief passages quoted in book review. This book can be exported from India only by Sri Sathya Sai Books and Publications Trust, Prasanthi Nilayam (India). International standard book no. International Standard Book No 81 - 7208 - 308 – 4 81 - 7208 - 118 - 9 (set) First Edition: Published by The Convener, Sri Sathya Sai Books & Publications Trust Prasanthi Nilayam, India, Pin code 515 134 Phone: 87375 Fax: 87236 STD: 08555 ISD: 91 - 8555 2 CONTENTS 1. Good Thoughts Herald New Year ..... 1 02. Hospitals Are Meant To Serve The Poor And Needy ..... 13 03. Vision Of The Atma ..... 25 04. Have Steady Faith In The Atma ..... 41 05. Know Thyself ..... 55 6. Ramayana - The Essence Of The Vedas ..... 69 07. Fill All Your Actions With Love .... -

Katarzyna Byłów-Antkowiak Phd Thesis

"OTHERS BEFORE SELF" : TIBETAN PEDAGOGY AND CHILDREARING IN A TIBETAN CHILDREN'S VILLAGE IN THE INDIAN HIMALAYA Katarzyna Byłów-Antkowiak A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2017 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11352 This item is protected by original copyright “Others Before Self”: Tibetan Pedagogy and Childrearing in a Tibetan Children’s Village in the Indian Himalaya Katarzyna Byłów-Antkowiak This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the Department of Social Anthropology, School of Philosophical, Anthropological and Film Studies, University of St Andrews July 2016 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Katarzyna Byłów-Antkowiak hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 74 500 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD Social Anthropology in September 2010; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2016 (part-time). Date …… signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD Social Anthropology in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

The Mahabharata Epic, Its Translations and Its Influence on Polish Intellectual Circles and General Readers

Iuvenilia Philologorum Cracoviensium, t. V Źródła Humanistyki Europejskiej 5 Kraków 2012, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego ISBN 978-83-233-3465-1, ISSN 2080-5802 IWONA MILEWSKA Instytut Orientalistyki UJ The Mahabharata Epic, Its Translations and Its Influence on Polish Intellectual Circles and General Readers The Mahabharata, one of the two most famous Indian or, to be more precise, Sanskrit epics, is up till modern days not fully known to Polish intellectuals nor to general readers. It is, among other reasons, due to the lack of its comprehen- sive translation into Polish. Even if the general information about Sanskrit literature, and in particular about the epics, or the Mahabharata, was circulating throughout Europe since the turn of 18th and 19th centuries, its way to Poland was a long one. Nowadays in Poland it is obviously easier to find competent information on India and its literature but still in most cases the detailed descriptions of the Ma- habharata epic are included in books directed to specialists rather than to gen- eral readers not to mention fragments of its direct translations into Polish which are till now extremely rare. It is known that the Europeans became deeply interested in India when the British started to be present there. They were the first to raise the interest in their literature. In this context such names as William Jones, Charles Wilkins or Henry Thomas Colebrooke should be mentioned. Their works, mostly of linguistics character, started to circulate in Europe at the turn of 18 and 19th centuries. In France one of the first scholars who focused also on India was A. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi: a Biographical Essay Mircea Eliade: the Romanian Roots, 1907–1945 Theosophy in the Nineteenth Century: an Annotated Bibliography

Theosophical History A Quarterly Journal of Research Volume V, No. 3 July 1994 ISSN 0951-497X THEOSOPHICAL HISTORY A Quarterly Journal of Research Founded by Leslie Price, 1985 Volume V, No. 3 July 1994 EDITOR of Emanuel Swedenborg to give but a few examples) that have had an influence James A. Santucci on or displayed an affinity to modern Theosophy. California State University, Fullerton The subscription rate for residents in the U.S., Mexico, and Canada is $14.00 (one year) ot $26.00 (two years). California residents, please add $1.08 (7.75%) sales tax onto the $14 rate or $2.01 onto the $26 rate. For residents outside North ASSOCIATE EDITORS America, the subscription rate is $16.00 (one year) or $30.00 (two years). Air mail Robert Boyd is $24.00 (one year) or $45.00 (two years). Single issues are $4.00. Subscriptions may also be paid in British sterling. All inquiries should be sent to James John Cooper Santucci, Department of Religious Studies, California State University, Fuller- University of Sydney ton, CA 92634-9480 (U.S.A.). Second class postage paid at Fullerton, California 92634. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Theosophical History (c/o James April Hejka-Ekins California State University, Stanislaus Santucci), Department of Religious Studies, California State University, Fullerton, CA 92634-9480 Jerry Hejka-Ekins The Editors assume no responsibility for the views expressed by authors in Nautilus Books Theosophical History. Robert Ellwood * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * University of Southern California GUIDELINES FOR SUBMISSION OF MANUSCRIPTS Joscelyn Godwin 1 The final copy of all manuscripts must be submitted on 8 ⁄2 x11 inch paper, Colgate University 1 4 double-spaced, and with margins of at least 1 ⁄ inches on all sides.