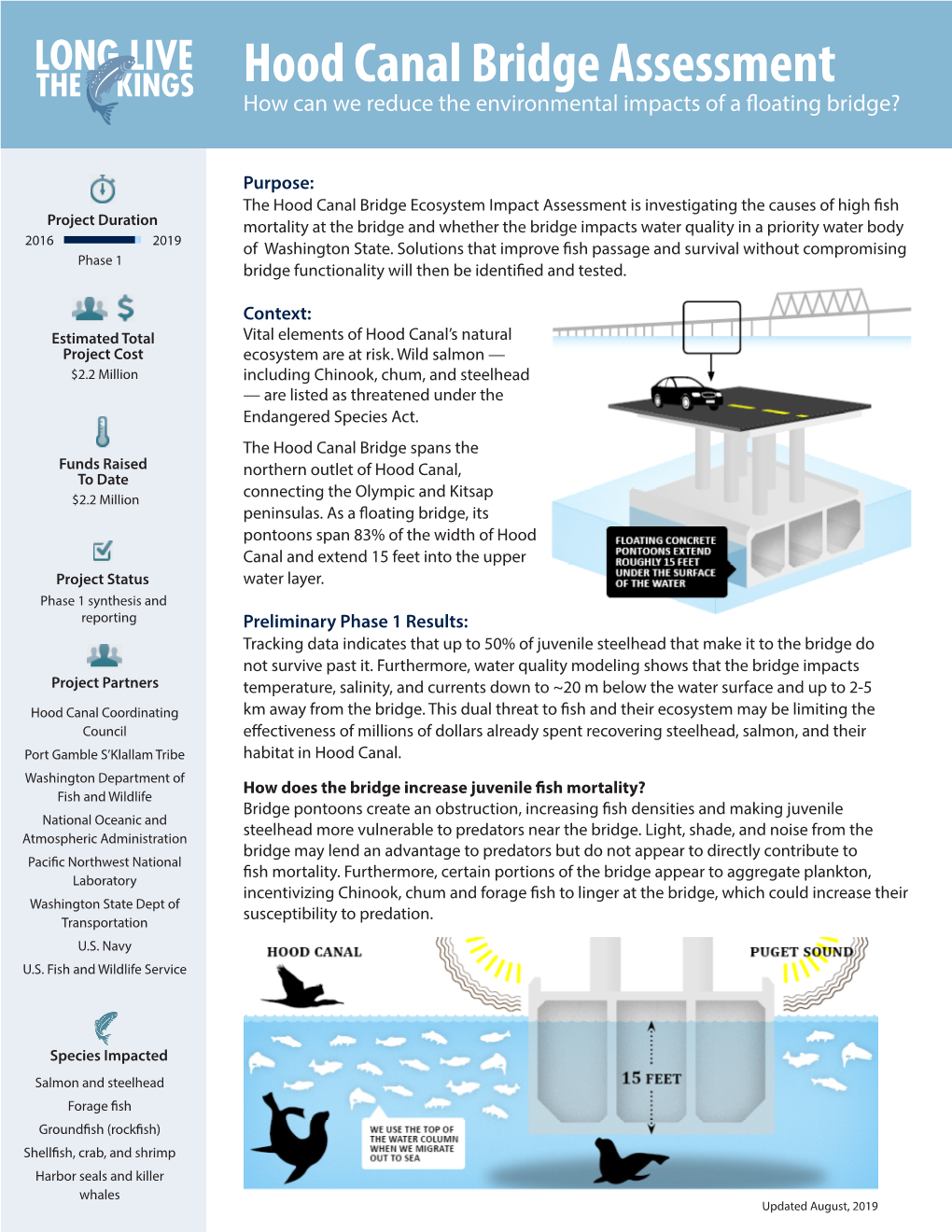

Hood Canal Bridge Assessment How Can We Reduce the Environmental Impacts of a Floating Bridge?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement of Qualifications Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project

Submitted by: Kiewit Pacific Co. Statement of Qualifications Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project Specification No. PW10-0128F Submitted to: Purchasing Office, Tacoma Public Utilities 3628 South 35th Street, Tacoma, WA 98409 June 8, 2010 Tab No. 1 - General Company Information & Team Structure Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project Project TAB NO.1 - GENERAL COMPANY INFORMATION AND TEAM STRUCTURE Kiewit Pacific Co., a wholly-owned subsidiary of Kiewit Infrastructure Group, Inc., will be the contracting party for this project, as indicated on Forms 3 and 4 in Tab No. 4 - Appendix C. As a wholly-owned subsidiary, none of the officers of Kiewit Pacific Co. (Kiewit) own stock. Incorporated on May 18, 1982, we can trace our history back to 1884, when Peter and Andrew Kiewit formed Kiewit Brothers, an Omaha masonry contracting partnership. Today, we are part of one of North America's largest and most respected construction and mining organizations. We take our place in the corporate structure of our parent company, Kiewit Infrastructure Group Inc., alongside Kiewit Construction Company and Kiewit Southern Co. Our affiliates and subsidiaries, as well as those of our parent company, operate from a network of offices throughout North America. We draw upon the Kiewit Corporation’s collective experience and personnel to assemble the strongest team possible for a given project. Therefore, work experience of such affiliates and subsidiaries is relevant in demonstrating our capabilities. For the Murray Morgan Bridge, we are supplementing our local talent with extensive moveable bridge expertise from our east coast operations, Kiewit Constructors, Inc. We are also utilizing our local subsidiary, General Construction Company (General), for mechanical and electrical expertise. -

Hood Canal Bridge Assessment Is a Floating Bridge Impacting the Hood Canal Ecosystem?

Hood Canal Bridge Assessment Is a Floating Bridge Impacting the Hood Canal Ecosystem? Purpose: The Hood Canal Bridge Ecosystem Impact Assessment will pinpoint the causes of high fish Project Duration mortality at the bridge and determine whether the bridge is lowering water quality in a 2016 2018 priority water body of Washington State. Solutions that do not substantially impact the bridge Phase 1 will then be identified and tested. Context: Estimated Total Coined “the wild side of Washington”, Project Cost many tourists and locals go to Hood $2.4 Million Canal to experience nature. However, vital elements of Hood Canal’s natural ecosystem are at risk. Wild salmon — including Chinook, chum, and Funds Raised steelhead — are listed as threatened To Date under the Endangered Species Act. Low $800,000 dissolved oxygen events periodically kill fish and ocean acidification threatens commercially important Project Status shellfish beds. Research Underway The Hood Canal Bridge carries State Route 104 across the northern outlet of Hood Canal, connecting the Olympic and Kitsap peninsulas. As a floating bridge, its pontoons span 83% of the width of Hood Canal and extend 15 feet into the upper water layer. Recent studies show higher mortality of juvenile steelhead Project Partners as they migrate past the bridge. Research also suggests that the bridge may disrupt water Hood Canal Coordinating circulation for all of Hood Canal, potentially increasing water temperatures, lowering dissolved Council oxygen levels and exacerbating the effects of ocean acidification and climate change. This dual Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe threat to migrating fish and their local marine ecosystem may be limiting the effectiveness of Washington Department of millions already spent recovering steelhead, salmon and their habitat in Hood Canal. -

Chapter 13 -- Puget Sound, Washington

514 Puget Sound, Washington Volume 7 WK50/2011 123° 122°30' 18428 SKAGIT BAY STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA S A R A T O 18423 G A D A M DUNGENESS BAY I P 18464 R A A L S T S Y A G Port Townsend I E N L E T 18443 SEQUIM BAY 18473 DISCOVERY BAY 48° 48° 18471 D Everett N U O S 18444 N O I S S E S S O P 18458 18446 Y 18477 A 18447 B B L O A B K A Seattle W E D W A S H I N ELLIOTT BAY G 18445 T O L Bremerton Port Orchard N A N 18450 A 18452 C 47° 47° 30' 18449 30' D O O E A H S 18476 T P 18474 A S S A G E T E L N 18453 I E S C COMMENCEMENT BAY A A C R R I N L E Shelton T Tacoma 18457 Puyallup BUDD INLET Olympia 47° 18456 47° General Index of Chart Coverage in Chapter 13 (see catalog for complete coverage) 123° 122°30' WK50/2011 Chapter 13 Puget Sound, Washington 515 Puget Sound, Washington (1) This chapter describes Puget Sound and its nu- (6) Other services offered by the Marine Exchange in- merous inlets, bays, and passages, and the waters of clude a daily newsletter about future marine traffic in Hood Canal, Lake Union, and Lake Washington. Also the Puget Sound area, communication services, and a discussed are the ports of Seattle, Tacoma, Everett, and variety of coordinative and statistical information. -

SR 104/SR 307: West Access to WSF (Kingston Ferry Terminal) the 15-Mile Long Corridor in Kitsap County Is Comprised of Two Segments Which Converge, Forming a Wye

Corridor Sketch Summary Printed at: 12:18 PM 10/29/2018 WSDOT's Corridor Sketch Initiative is a collaborative planning process with agency partners to identify performance gaps and select high-level strategies to address them on the 304 corridors statewide. This Corridor Sketch Summary acts as an executive summary for one corridor. Please review the User Guide for Corridor Sketch Summaries prior to using information on this corridor: SR 104/SR 307: West Access to WSF (Kingston Ferry Terminal) The 15-mile long corridor in Kitsap County is comprised of two segments which converge, forming a wye. The first segment runs along State Route 104 travelling between the SR 104/SR 3 intersection, located immediately east of the Hood Canal Bridge, and the holding area for the Kingston Ferry Terminal. The second segment runs along SR 307 running between Poulsbo at the SR 305 junction and the SR 104 intersection. Additionally, there is a .3-mile couplet in Kingston. The character of the corridor is primarily rural with some large lot homes and residential developments scattered throughout. The area along the corridor is primarily undeveloped with a significant amount of forested area. The eastern and western ends of the corridor, near Kingston and Poulsbo respectively, are more urban in character with small concentrations of residential, commercial, and industrial land uses. The corridor passes through rolling terrain and forested land. Current Function SR 104 runs east-west connecting the eastern Olympic Peninsula, Kitsap Peninsula, and central Puget Sound region and includes the Kingston-Edmonds Ferry Route. SR 307 travels within Kitsap County, providing a direct connection between Poulsbo and SR 104. -

9. Transportation Appendix

TRANSPORTATION TRANSPORTATION APPENDIX I. TRANSPORTATION INVENTORY This section of the transportation element summarizes the existing transportation facilities and services currently in use in the unincorporated portions of Kitsap County. The inventory includes a variety of multimodal facilities and describes all travel modes used in the County for mobility. A. Public Highways, Arterials, and Roadways The Kitsap County peninsula is surrounded by water on three sides, and is connected to the mainland at the southern end of the county. The two main routes into Kitsap County from the south are SR 16, from Pierce County, and SR 3 from Mason County. SR 16 connects Kitsap County to Pierce County, including the City of Tacoma, via the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. The Tacoma Narrows Bridge also provides access to all points east of Puget Sound. In contrast, SR 3 leads to rural Mason County and to the Olympic Peninsula. Figure TR-1, in Part III, Fold Out Figures, of the Comprehensive Plan, indicates the major travel corridors in Kitsap County including both state routes and county/city routes. There are three main bridges serving Kitsap County: Tacoma Narrows (SR 16), Agate Pass (SR 305), and Hood Canal (SR 104). Access to the Olympic Peninsula from the northern half of the county is near Port Gamble via the Hood Canal Bridge, which crosses the Hood Canal into Jefferson County. All other access points to Kitsap County are by ferry on the eastern side of the County. These points include Bremerton and Bainbridge in central Kitsap; Southworth in south Kitsap; and Kingston in the north. -

Hood Canal Bridge Ecosystem Impact Assessment Plan: Framework and Phase 1 Details FINAL – September 27, 2016

Hood Canal Bridge Ecosystem Impact Assessment Plan: Framework and Phase 1 Details FINAL – September 27, 2016 Prepared by: Hood Canal Bridge Assessment Team and contributing experts (see reverse) Cite document as: Hood Canal Bridge Assessment Team. 2016. Hood Canal Bridge Ecosystem Impact Assessment Plan: Framework and Phase 1 Details. Long Live the Kings, Seattle, WA. Bridge Assessment Team Megan Moore, NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center* Tarang Khangaonkar, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory* Barry Berejikian, NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center* Hans Daubenberger, Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe* Steve Jeffries, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife* Paul McCollum, Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe Erik Neatherlin, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Scott Pearson, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife* Chris Harvey, NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center* Austen Thomas, Smith-Root* Carl Ward, Washington Department of Transportation John Wynands, Washington Department of Transportation Contributors Kevin Redman, RPS Evans Hamilton Daniel Deng, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory Tim Essington, University of Washington Monique Lance, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Marshal Richmond, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory Julie Keister, University of Washington Ken Warheit, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Coordinators Michael Schmidt, Long Live the Kings+ Iris Kemp, Long Live the Kings Susan O’Neil, Long Live the Kings Lucas Hall, Long Live the Kings *Principals +Project Manager and Lead. For -

Closure Mitigation Folio Replacement Project WSDOT Has Updated the Closure Mitigation Budget Into 2009 Dollars

May 2008 CLOSURE MITIGATION BUDGET The Hood Canal Bridge project began in October 1997. At that time, the cost estimated for Hood Canal Bridge May 2008 the closure mitigation portion of the work was $10 million. Retrofit and East-half Closure Mitigation Folio Replacement Project WSDOT has updated the Closure Mitigation Budget into 2009 dollars. The closure mitigation Hood Canal Bridge Retrofit and East Half Replacement Project budget reflects current costs spent from November 2005 through today and projected East-half Replacement expenditures through the May-June 2009 bridge closure and replacement. Completion Goal: 2009 The Hood Canal Bridge is an economic lifeline for the people and West-half Retrofit Completion Goal : 2010 CLOSURE MITIGATION businesses of the Olympic Peninsula and a gateway for visitors Our estimate is currently $11.8 million. The costs to implement the plan’s transportation PLAN HISTORY coming to experience the wonders of the region. options, including the water shuttle service, park and ride lots and transportation Q. Where is the bridge? Since 1997, community members from both connections, contributed to the increased budget estimate. the Olympic and Kitsap Peninsulas, the A. The Hood Canal Bridge is located The project is looking for ways to meet the $10 million budget through: 1) Evaluating the water Peninsula Regional Transportation and Planning shuttle service level; 2) Administering the water shuttle dock construction contract. WSDOT between Kitsap and Jefferson counties Organization (PRTPO) and Washington State will continue refining the budget numbers when the water shuttle service company is selected. at the mouth of the Hood Canal. Department of Transportation worked together Q. -

Hood Canal Bridge East-Half Replacement Closure Mitigation Plan – Preferred Options

Hood Canal Bridge East-Half Replacement Closure Mitigation Plan – Preferred Options February 2000 Washington State Department of Transportation Hood Canal Bridge Replacement Project Committees Stakeholder's Committee Advisory Committee (HCBRSC) (HCBRAC) Gary Demich, Chair Dan DiGuilio, Chair Washington State Department of Transportation--Olympic Region Clallam Transit John Law Bruce Laurie City of Bremerton Jefferson County Public Works Department Martha Ireland Curtis Stacey Clallam County Jefferson Transit Bob Smith Chuck Shank Clallam County Kitsap County Public Works Julie Garrison John Clauson & Bob Ferguson Jefferson County Emergency Services Kitsap Transit Melanie Bozak & Jeff Hamm Bill Bullock Jefferson Transit Mason County Public Works Chris Endresen Doug Parrish Kitsap County Parrish Trucking Wendy Clark Gary Kenworthy Kitsap Transit City of Port Angeles Mary Jo Cady Brad Collins Mason County Port Angeles Public Works Ken Miller & David VanderPol Ken Attebery Oak Harbor Freight Lines Port of Bremerton Harry Fulton Phil Dorn Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe Port Gamble Development Authority Forrest Rambo & David Timmons Herb Beck & Larry Crockett Port Townsend Port of Port Townsend Tim Caldwell Jim Bunger Port Townsend Chamber of Commerce Puget Sound Transfer & Storage Dan Eckstein Janet Thornbrue US Navy City of Shelton Terry McCarthy Amity Trowbridge Washington State Ferries Washington State Department of Transportation--Olympic Region Bob Jones Washington State Department of Transportation--Planning Ray Deardorf Washington State Ferries Jack Harmon Victoria Express Ferry Hood Canal Bridge East-Half Replacement Closure Mitigation Plan – Preferred Options February 2000 Our mission is to identify and prioritize options within funding limits that will lessen the impact to users of the Hood Canal Bridge during the East-Half Replacement Project. -

News from Volume 36, Issue 1 January 2015 Wakefield Contributes Patsey Family Collection

Newsfrom Volume 36, Issue 1 January 2015 Wakefield Contributes Patsey Family Collection The eldest man from the Patsey clan, George Wakefield, recently came into Blyn to record an oral history of his memories of growing up on the Patsey property in Port Hadlock owned by his great-grandparents, Young and Lucy Patsey. George was born in February 27, 1933 to Gertrude Patsey and John Malia Wakefield. Wakefield was an Englishman who had come cross- country from Maine. There are many members of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe who descend from the Old Patsey (Twana name Shubald), who died in 1911 and was thought to be the last full-blooded Georgia and George Wakefield member of the Twana (Skokomish) Tribe. Old Patsey and his wife Jennie were the parents of Young Patsey, born at Seabeck in 1854, where both Old and Young worked at the mill there. Young married Lucy Dexter, the daughter of Old Dexter from Jamestown. The family moved to Port Hadlock in 1887 when the Seabeck mill burned down, and both father and son began working at the Washington Mill in Hadlock. The Patseys lived in Port Hadlock, on land next door to the Old Alcohol Plant, near the present day Port Hadlock Marina. The Patsey’s next door neighbors were the family of the Prince of (Continued on page 2) Patsey Family Collection 1, 2 Funding Secured for Dungeness River Projects 11 Dr. Locke to Join Clinic; Tribe to Connect to City of Library Corner 12 Sequim Wastewater Utility 3 Obama Commits to Native American Youth; January Message from our Tribal Chair/CEO 4, 5 Elders Luncheon -

Hood Canal Bridge) This Seven-Mile Long North-South Corridor in Kitsap County Is Located Between the City of Poulsbo and the Hood Canal Bridge

Corridor Sketch Summary Printed at: 12:33 PM 9/20/2018 WSDOT's Corridor Sketch Initiative is a collaborative planning process with agency partners to identify performance gaps and select high-level strategies to address them on the 304 corridors statewide. This Corridor Sketch Summary acts as an executive summary for one corridor. Please review the User Guide for Corridor Sketch Summaries prior to using information on this corridor: SR 3: SR 305 Jct (Poulsbo vicinity) to SR 104 Jct (Hood Canal Bridge) This seven-mile long north-south corridor in Kitsap County is located between the city of Poulsbo and the Hood Canal Bridge. The corridor runs from the State Route 3/SR 305 interchange at Poulsbo to the intersection with RS 104. The corridor is very rural in character and does not pass through any incorporated communities. The majority of the surrounding land is undeveloped with mixed conifer forest or very low density rural residential. Other land uses along the corridor include some industrial uses scattered throughout such as gravel pits, manufacturing, and several parks. The corridor is lightly populated with commercial activities and residences having direct access to the corridor. The northern portion of the corridor runs along the Hood Canal leading up to the Hood Canal Bridge. Port Gamble Forest Heritage Park and several Olympic Resources Trails are east of the corridor. The corridor passes through rolling terrain for its entire length. Current Function SR 3 is the primary north-south route on the Kitsap Peninsula running from the city of Shelton to the Hood Canal Bridge, and the only land route into Kitsap County. -

Tracking Fish and Human Response to Abrupt Environmental Change at Tse-Whit-Zen: a Large Native American Village on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington State

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Summer 8-20-2013 Tracking Fish and Human Response to Abrupt Environmental Change at Tse-whit-zen: A Large Native American Village on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington State Kathryn Anne Mohlenhoff Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Mohlenhoff, Kathryn Anne, "Tracking Fish and Human Response to Abrupt Environmental Change at Tse- whit-zen: A Large Native American Village on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington State" (2013). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1052. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1052 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Tracking Fish and Human Response to Abrupt Environmental Change at Tse-whit-zen: A Large Native American Village on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington State by Kathryn Anne Mohlenhoff A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Anthropology Thesis Committee: Virginia L. Butler, Chair Kenneth M. Ames Shelby L. Anderson Portland State University 2013 Abstract Evidence of large earthquakes occurring along the Pacific Northwest Coast is reflected in coastal stratigraphy from Oregon to British Columbia, where there also exists an extensive archaeological record of Native American occupation. -

HOOD CANAL BRIDGE a FLOATING LIFT DRAW BRIDGE MICHAEL J. ABRAHAMS, PE Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc. New York

HOOD CANAL BRIDGE A FLOATING LIFT DRAW BRIDGE BY MICHAEL J. ABRAHAMS, P.E. parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc. New York, New York 10119 Introduction The Hood Canal is a deep channel branching off Puget Sound in the State of Washington. In 1961, a mile long floating bridge designed by the Washington Toll Bridge Authority was completed across the Canal. Because of the depth of the water, over 300 feet, a fixed bridge was not economically feasible at the site. Other site characteristics determined the features of the bridge. To allow for tidal changes of over 18 feet and to provide longitudinal restraint to the floating portion of the bridge, a 280-foot-long, hinged, transition steel truss was provided at each end of the floating portion. The bridge was transversely anchored to the canal bottom with steel cable anchor lines attached to concrete gravity anchors. In order to provide the 600 foot opening necessary for accomodating large naval ships, the center portion of the bridge incorporated two movable draw spans. The pontoons utilized cast- in-place reinforced concrete with a small amount of longitudinal prestress. Frequent storms coming off the Pacific Ocean subject the Hood Canal bridge to the dynamic forces induced by waves. On February 13, 1979, a particularly severe storm, remembered by local residents for the extensive damage it did to the surrounding forests, destroyed the western portion of the bridge. New Bridge In order to restore traffic as quickly as possible and, at the same time, provide for a new bridge, a three stage construction plan was developed (see Figure 1).