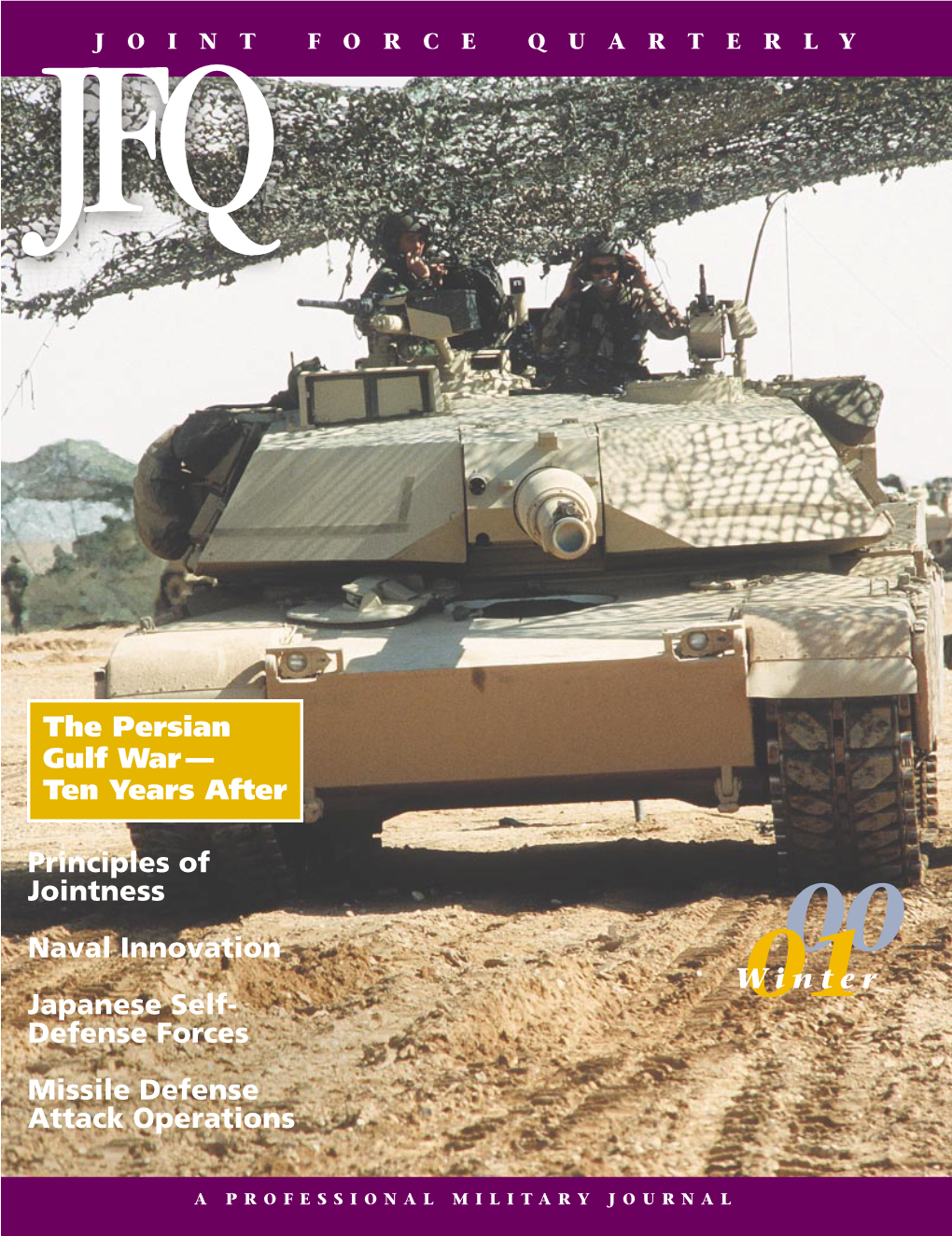

Joint Force Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contributed by Darryl Baker

Decomm,SS′Omng UNI丁ED SRAT格§ SHIP TORTUeA IL§D「26) ON BOARD u§§ TOR丁UeA (LiD。21) INACTlVATION SHIP MAiNTENANCE FAC看LITY, VALしEJO, CALiFORNIA MONDAY 26 JANUARY NINETEEN HUNDRED AND SEVENTY AT lO:00 O’CLOCK DECOMMl§§iON看Ne C各R格MONY DECOMMISSIONiNG Presentation o書lhe USS TORTuGA (LSD"26) to Commanding O楯cer, Inac章ivation Ship Maintenance Fac珊y Vallejo HISTORY OF USS TORTUeA (し§D〃26) U.S.S. TOR同GÅ was built a‥he U.S. Naval Shipy叫Boston, and COmmissioned on 8 June 1945. She joined 〔he Amphibious Force, U.S. Pacific FIeet and served as paJ…f 〔he Mobile Support Fbrce before being decommjssioned in Åugust 1947. The firs亡rsD to be rccommissioned ahe‥he outbrcak of Korean Hosulities’TORTUGÅ was reac`ivated at San Diego qu 15 S叩mbe[ 1950. (The ILSD’s proven capabiliries jn World War II dictaed tha' they all be re‘伽issioned for Iforcan service; this was true of no other type Ship.) TORTUGA par〔icipated in the Inchon Landing in February 195l and in various other fleet呼重atichs言ncluding the 1953 prisoner-Of-War exchangc. Now hom叩re吊n I‘Ong Beach, TORmGA dやkys rcguhrly to the Western pa。fic for drty with the U.S. Seventh Fha In recent years, the frequency of these deployments has increased jn sup叩of the Viet- namese act-On. TORTUGA and orher ISD,s have been insmmenta=n OPerational support in the Rqublic of Vierrlam, In August and Sq,〔enber 1964, TORTUGA stcaned in company Wi〔h other ships of Amphibious Squadron皿ee for 58 days con亡inuous・ ly near the Vie〔namese coast’rendy to land her embarked M壷nes and Ianding craft on a few hours・ no〔ice. -

July Slater Signals

SLATER SIGNALS The Newsletter of the USS SLATER's Volunteers By Timothy C. Rizzuto, Executive Director Destroyer Escort Historical Museum USS Slater DE-766 PO Box 1926 Albany, NY 12201-1926 Phone (518) 431-1943, Fax 432-1123 Vol. 18 No. 7, July 2015 It’s hard to believe that the summer is half over and I’m already writing the July SIGNALS. We had some very special visitors this month. First and foremost were Dale and Linda Drake. This was special because Linda is the daughter of the late Master Chief Gunner’s Mate Sam Saylor and, it’s safe to say, without Sam Saylor, there would be no USS SLATER preservation. Linda recalled that for years her visits were constantly interrupted with Sam's words, "Well, I take care of some SLATER business." It was the ship that was Sam's focus and sustained him through the last 20 years of his life. Linda and Dale made the trip from Omaha specifically to see USS SLATER because this was Linda’s first chance to see the fruit of all her father’s effort. Board President Tony Esposito greeted them as they toured the ship from stem to stern. Linda’s husband Dale is a former Marine, and he left Linda on the Observation Deck so he could take the bilge tour. He wanted to see everything. I do believe if we could get them to relocate to Albany we’d have two more dedicated volunteers. Linda brought along Sam's burial flag which we will fly for the month of August and then retire it to the USS CONNOLLY display in Sam’s honor. -

JMSDF Staff College Review Volume 1 Number 2 English Version (Selected)

JMSDF Staff College Review Volume 1 Number 2 English Version (Selected) JMSDF STAFF COLLEGE REVIEW JAPAN MARITIME SELF-DEFENSE FORCE STAFF COLLEGE REVIEW Volume1 Number2 English Version (Selected) MAY 2012 Humanitarian Assistance / Disaster Relief : Through the Great East Japan Earthquake Foreword YAMAMOTO Toshihiro 2 Japan-U.S. Joint Operation in the Great East Japan Earthquake : New Aspects of the Japan-U.S. Alliance SHIMODAIRA Takuya 3 Disaster Relief Operations by the Imperial Japanese Navy and the US Navy in the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake : Focusing on the activities of the on-site commanders KURATANI Masashi 30 of the Imperial Japanese Navy and the US Navy Contributors From the Editors Cover: Disaster Reief Operation by LCAC in the Great East Japan Earthquake 1 JMSDF Staff College Review Volume 1 Number 2 English Version (Selected) JMSDF Staff College Review Volume 1 Number 2 English Version (Selected) Foreword It is one year on that Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force Staff College Review was published in last May. Thanks to the supports and encouragements by the readers in and out of the college, we successfully published this fourth volume with a special number. It is true that we received many supports and appreciation from not only Japan but also overseas. Now that HA/DR mission has been widely acknowledged as military operation in international society, it is quite meaningful for us who have been through the Great East Japan Earthquake to provide research sources with international society. Therefore, we have selected two papers from Volume 1 Number 2, featuring HA/DR and published as an English version. -

Winter 2020 Full Issue

Naval War College Review Volume 73 Number 1 Winter 2020 Article 1 2020 Winter 2020 Full Issue The U.S. Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The U.S. (2020) "Winter 2020 Full Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 73 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol73/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naval War College: Winter 2020 Full Issue Winter 2020 Volume 73, Number 1 Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2020 1 Naval War College Review, Vol. 73 [2020], No. 1, Art. 1 Cover Two modified Standard Missile 2 (SM-2) Block IV interceptors are launched from the guided-missile cruiser USS Lake Erie (CG 70) during a Missile Defense Agency (MDA) test to intercept a short-range ballistic-missile target, conducted on the Pacific Missile Range Facility, west of Hawaii, in 2008. The SM-2 forms part of the Aegis ballistic-missile defense (BMD) program. In “A Double-Edged Sword: Ballistic-Missile Defense and U.S. Alli- ances,” Robert C. Watts IV explores the impact of BMD on America’s relationship with NATO, Japan, and South Korea, finding that the forward-deployed BMD capability that the Navy’s Aegis destroyers provide has served as an important cement to these beneficial alliance relationships. -

Pull Together Fall/Winter 2014

Preservation, Education, and Commemoration Vol. 53, No. 1 Fall-Winter 2013/2014 PULL TOGETHER Newsletter of the Naval Historical Foundation An AEGIS Legacy: Wayne Meyer’s History War Rooms, Page 3 Remembering September 16, 2013. Page 6 Also in the issue: Olympia update, pp. 9–10 ; Navy Museum News, pp. 12–13; Naval History News, pp. 14–16; News from the NHF, pp. 17–20; Remembering Rear Admiral Kane pp. 22-23. Message From the Chairman Last month, you received the Foundation’s year-end appeal from our president, Rear Adm. John Mitchell. If you sent your donations earlier this year, or in response to this appeal, thank you! For those of you contemplating a gift, I hope you’ll refl ect on our successes in “preserving and honoring the legacy of those who came before us; educating and inspiring the generations who will follow.” We’ve got much left to do, and your support makes all the difference. This is a great time to make that tax-deductible donation or IRA distribution direct to NHF! The year-end appeal featured a 1948 letter from then-NHF Vice President Fleet Adm. Chester W. Nimitz to then-NHF President Fleet Adm. Ernest J. King referring to the budget and political woes encountered 65 years ago in the nation’s capital: “I, for one, am glad to be away from that trouble spot….” Yet despite the challenges King faced, including a series of debilitating strokes, he remained strongly committed to growing the NHF and educating the American public about this nation’s great naval heritage. -

American Naval Policy, Strategy, Plans and Operations in the Second Decade of the Twenty- First Century Peter M

American Naval Policy, Strategy, Plans and Operations in the Second Decade of the Twenty- first Century Peter M. Swartz January 2017 Select a caveat DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. CNA’s Occasional Paper series is published by CNA, but the opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of CNA or the Department of the Navy. Distribution DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. PUBLIC RELEASE. 1/31/2017 Other requests for this document shall be referred to CNA Document Center at [email protected]. Photography Credit: A SM-6 Dual I fired from USS John Paul Jones (DDG 53) during a Dec. 14, 2016 MDA BMD test. MDA Photo. Approved by: January 2017 Eric V. Thompson, Director Center for Strategic Studies This work was performed under Federal Government Contract No. N00014-16-D-5003. Copyright © 2017 CNA Abstract This paper provides a brief overview of U.S. Navy policy, strategy, plans and operations. It discusses some basic fundamentals and the Navy’s three major operational activities: peacetime engagement, crisis response, and wartime combat. It concludes with a general discussion of U.S. naval forces. It was originally written as a contribution to an international conference on maritime strategy and security, and originally published as a chapter in a Routledge handbook in 2015. The author is a longtime contributor to, advisor on, and observer of US Navy strategy and policy, and the paper represents his personal but well-informed views. The paper was written while the Navy (and Marine Corps and Coast Guard) were revising their tri- service strategy document A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, finally signed and published in March 2015, and includes suggestions made by the author to the drafters during that time. -

Commodore John Barry

Commodore John Barry Day, 13th September Commodore John Barry (1745-1803) a native of County Wexford, Ireland was a Continental Navy hero of the American War for Independence. Barry’s many victories at sea during the Revolution were important to the morale of the Patriots as well as to the successful prosecution of the War. When the First Congress, acting under the new Constitution of the United States, authorized the raising and construction of the United States Navy, President George Washington turned to Barry to build and lead the nation’s new US Navy, the successor to the Continental Navy. On 22 February 1797, President Washington conferred upon Barry, with the advice and consent of the Senate, the rank of Captain with “Commission No. 1,” United States Navy, effective 7 June 1794. Barry supervised the construction of his own flagship, the USS UNITED STATES. As commander of the first United States naval squadron under the Constitution, which included the USS CONSTITUTION (“Old Ironsides”), Barry was a Commodore with the right to fly a broad pennant, which made him a flag officer. Commodore John Barry By Gilbert Stuart (1801) John Barry served as the senior officer of the United States Navy, with the title of “Commodore” (in official correspondence) under Presidents George Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The ships built by Barry, and the captains selected, as well as the officers trained, by him, constituted the United States Navy that performed outstanding service in the “Quasi-War” with France, in battles with the Barbary Pirates and in America’s Second War for Independence (the War of 1812). -

New Vietnam War Exhibit Opens Aboard USCGC TANEY

VOLUME XIX, ISSUE NUMBER 1 Spring 2017 New Vietnam War Exhibit Opens Aboard USCGC TANEY A new exhibit has opened in the Ward Room aboard USCGC TANEY. "To Patrol and Interdict: Operation Market Time" uses artifacts, images, motion picture footage and models to tell the story of USCGC TANEY's 1969-70 deployment to Vietnam within the context of the wider war. The creation of "To Patrol and Interdict" was a truly cooperative enterprise which used the combined resources of Historic Ships in Baltimore, the AMVETS Department of Maryland, and numerous TANEY sailors from the Vietnam era to pull together a compelling exhibit with a broad range of features. Professionally produced text and graphics panels were paid for through a donation from AMVETS, the well-known veterans service and advocacy organization. Special thanks to former TANEY crew who provided many compelling artifacts for the exhibit. These include a spent 5"/38 caliber cartridge casing from one of the ship's 1969 gunfire support missions, courtesy of CAPT Ted Sampson, USCG (Ret) who had served as CIC Officer during the deployment. Artifacts include a South Vietnamese Another gift from a TANEY sailor was a DVD transfer fishing boat flag, memorabilia collected of film footage showing many of TANEY's patrol by crew and a vintage Coast Guard enlisted tropical dress white uniform. evolutions, such as boarding and searching Vietnamese vessels, naval gunfire support missions, and underway replenishment in the South China Sea. The footage, which came courtesy of CAPT Jim Devitt (Ret), who had been TANEY's First Lieutenant in Vietnam, also includes scenes from many of the foreign ports visited such as Hong Kong, Bangkok, Sasebo, and Kaohsiung, Taiwan. -

Dd215 Borie Link

A Fight to the Death: The USS Borie, 31 October to 2 November 1943 She had been designed for an earlier war. Launched in 1919, the USS Borie had been the ultimate in destroyer design. She was fast – capable of up to 35 knots (40 mph) and well armed for the time with four 4” guns, a bank of 21” torpedo tubes and depth charges. By 1943, though, she was showing her age. Borie and her sisters could keep up with the new Fast Carriers in terms of speed but little else. Newer and far more powerful designs were coming out in flocks (the Navy would commission well over one hundred of the Fletcher class alone during WWII) and nothing else would do to escort the fast-stepping and long-legged carriers across the vast Pacific. She did wind up as a carrier escort, though. She and two of her sisters, USS Goff and USS Barry were assigned to be part of a hunter-killer task group, Task Group 21.14. centered around the USS Card, an escort carrier. The escort carrier concept arose to fill in gaps in air coverage for convoys crossing the U-Boat-infested Atlantic. Unlike their larger and more glamorous kin, the escort carriers (CVE) were built on merchant or tanker hulls with a flight deck and a small “island” structure nailed on top. They usually carried 21 aircraft: nine or ten “Widcat” fighters and a dozen or so “Avenger” torpedo bombers rigged to carry depth-charges. Running flat out, with everything open but the toolbox, a CVE could make about 20 knots. -

The Graybeards Presidential Envoy to UN Forces: Kathleen Wyosnick the Magazine for Members and Veterans of the Korean War

Staff Officers The Graybeards Presidential Envoy to UN Forces: Kathleen Wyosnick The Magazine for Members and Veterans of the Korean War. P.O. Box 3716, Saratoga, CA 95070 The Graybeards is the official publication of the Korean War Veterans Association, PH: 408-253-3068 FAX: 408-973-8449 PO Box, 10806, Arlington, VA 22210, (www.kwva.org) and is published six times Judge Advocate: Sherman Pratt per year for members of the Association. 1512 S. 20th St., Arlington, VA 22202 PH: 703-521-7706 EDITOR Vincent A. Krepps 24 Goucher Woods Ct. Towson, MD 21286-5655 Dir. for Washington, DC Affairs: J. Norbert Reiner PH: 410-828-8978 FAX: 410-828-7953 6632 Kirkley Ave., McLean, VA 22101-5510 E-MAIL: [email protected] PH/FAX: 703-893-6313 MEMBERSHIP Nancy Monson National Chaplain: Irvin L. Sharp, PO Box 10806, Arlington, VA 22210 16317 Ramond, Maple Hights, OH 44137 PH: 703-522-9629 PH: 216-475-3121 PUBLISHER Finisterre Publishing Incorporated National Asst. Chaplain: Howard L. Camp PO Box 12086, Gainesville, FL 32604 430 S. Stadium Dr., Xenia, OH 45385 E-MAIL: [email protected] PH: 937-372-6403 National KWVA Headquarters Korean Ex-POW Associatiion: Elliot Sortillo, President PRESIDENT Harley J. Coon 2533 Diane Street, Portage, IN 56368-2609 4120 Industrial Lane, Beavercreek, OH 45430 National VA/VS Representative: Norman S. Kantor PH: 937-426-5105 or FAX: 937-426-8415 2298 Palmer Avenue, New Rochelle, NY 10801-2904 E-MAIL: [email protected] PH: 914-632-5827 FAX: 914-633-7963 Office Hours: 9am to 5 pm (EST) Mon.–Fri. -

US Navy Program Guide 2012

U.S. NAVY PROGRAM GUIDE 2012 U.S. NAVY PROGRAM GUIDE 2012 FOREWORD The U.S. Navy is the world’s preeminent cal change continues in the Arab world. Nations like Iran maritime force. Our fleet operates forward every day, and North Korea continue to pursue nuclear capabilities, providing America offshore options to deter conflict and while rising powers are rapidly modernizing their militar- advance our national interests in an era of uncertainty. ies and investing in capabilities to deny freedom of action As it has for more than 200 years, our Navy remains ready on the sea, in the air and in cyberspace. To ensure we are for today’s challenges. Our fleet continues to deliver cred- prepared to meet our missions, I will continue to focus on ible capability for deterrence, sea control, and power pro- my three main priorities: 1) Remain ready to meet current jection to prevent and contain conflict and to fight and challenges, today; 2) Build a relevant and capable future win our nation’s wars. We protect the interconnected sys- force; and 3) Enable and support our Sailors, Navy Civil- tems of trade, information, and security that enable our ians, and their Families. Most importantly, we will ensure nation’s economic prosperity while ensuring operational we do not create a “hollow force” unable to do the mission access for the Joint force to the maritime domain and the due to shortfalls in maintenance, personnel, or training. littorals. These are fiscally challenging times. We will pursue these Our Navy is integral to combat, counter-terrorism, and priorities effectively and efficiently, innovating to maxi- crisis response. -

United States Navy (USN) Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) Request Logs, 2009-2017

Description of document: United States Navy (USN) Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) request logs, 2009-2017 Requested date: 12-July-2017 Release date: 12-October-2017 Posted date: 03-February-2020 Source of document: Department of the Navy - Office of the Chief of Naval Operations FOIA/Privacy Act Program Office/Service Center ATTN: DNS 36 2000 Navy Pentagon Washington DC 20350-2000 Email:: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site, and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF NAVAL OPERATIONS 2000 NAVY PENTAGON WASHINGTON, DC 20350-2000 5720 Ser DNS-36RH/17U105357 October 12, 2017 Sent via email to= This is reference to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request dated July 12, 2017.