Delving Deeper Critical Challenges for 21St Century Deep-Sea Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 REVISED J Caveorum Profile

Document SPRFMO-III-SWG-12 Information describing Jasus caveorum fisheries relating to the South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation REVISED 20 February 2007 DRAFT 1. Overview.......................................................................................................................2 2. Taxonomy.....................................................................................................................3 2.1 Phylum..................................................................................................................3 2.2 Class.....................................................................................................................3 2.3 Order.....................................................................................................................3 2.4 Family...................................................................................................................3 2.5 Genus and species.................................................................................................3 2.6 Scientific synonyms...............................................................................................3 2.7 Common names.....................................................................................................3 2.8 Molecular (DNA or biochemical) bar coding.........................................................3 3. Species characteristics....................................................................................................3 3.1 Global distribution -

Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems – Processes and Practices in the High Seas Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems Processes and Practices in the High Seas

ISSN 2070-7010 FAO 595 FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE TECHNICAL PAPER 595 Vulnerable marine ecosystems – Processes and practices in the high seas Vulnerable marine ecosystems Processes and practices in the high seas This publication, Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems: processes and practices in the high seas, provides regional fisheries management bodies, States, and other interested parties with a summary of existing regional measures to protect vulnerable marine ecosystems from significant adverse impacts caused by deep-sea fisheries using bottom contact gears in the high seas. This publication compiles and summarizes information on the processes and practices of the regional fishery management bodies, with mandates to manage deep-sea fisheries in the high seas, to protect vulnerable marine ecosystems. ISBN 978-92-5-109340-5 ISSN 2070-7010 FAO 9 789251 093405 I5952E/2/03.17 Cover photo credits: Photo descriptions clockwise from top-left: Acanthagorgia spp., Paragorgia arborea, Vase sponges (images courtesy of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada); and Callogorgia spp. (image courtesy of Kirsty Kemp, the Zoological Society of London). FAO FISHERIES AND Vulnerable marine ecosystems AQUACULTURE TECHNICAL Processes and practices in the high seas PAPER 595 Edited by Anthony Thompson FAO Consultant Rome, Italy Jessica Sanders Fisheries Officer FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Rome, Italy Merete Tandstad Fisheries Resources Officer FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Rome, Italy Fabio Carocci Fishery Information Assistant FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Rome, Italy and Jessica Fuller FAO Consultant Rome, Italy FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2016 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

New Zealand Fishes a Field Guide to Common Species Caught by Bottom, Midwater, and Surface Fishing Cover Photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola Lalandi), Malcolm Francis

New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing Cover photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola lalandi), Malcolm Francis. Top left – Snapper (Chrysophrys auratus), Malcolm Francis. Centre – Catch of hoki (Macruronus novaezelandiae), Neil Bagley (NIWA). Bottom left – Jack mackerel (Trachurus sp.), Malcolm Francis. Bottom – Orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), NIWA. New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No: 208 Prepared for Fisheries New Zealand by P. J. McMillan M. P. Francis G. D. James L. J. Paul P. Marriott E. J. Mackay B. A. Wood D. W. Stevens L. H. Griggs S. J. Baird C. D. Roberts‡ A. L. Stewart‡ C. D. Struthers‡ J. E. Robbins NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Wellington 6241 ‡ Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, 6011Wellington ISSN 1176-9440 (print) ISSN 1179-6480 (online) ISBN 978-1-98-859425-5 (print) ISBN 978-1-98-859426-2 (online) 2019 Disclaimer While every effort was made to ensure the information in this publication is accurate, Fisheries New Zealand does not accept any responsibility or liability for error of fact, omission, interpretation or opinion that may be present, nor for the consequences of any decisions based on this information. Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries website at http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-and-resources/publications/ A higher resolution (larger) PDF of this guide is also available by application to: [email protected] Citation: McMillan, P.J.; Francis, M.P.; James, G.D.; Paul, L.J.; Marriott, P.; Mackay, E.; Wood, B.A.; Stevens, D.W.; Griggs, L.H.; Baird, S.J.; Roberts, C.D.; Stewart, A.L.; Struthers, C.D.; Robbins, J.E. -

Order ZEIFORMES PARAZENIDAE Parazens P.C

click for previous page Zeiformes: Parazenidae 1203 Order ZEIFORMES PARAZENIDAE Parazens P.C. Heemstra, South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity, South Africa iagnostic characters: Small to moderate-sized (to 30 cm) oblong fishes, the head and body com- Dpressed; body depth slightly less than head length, contained 2.6 to 2.9 times in standard length; head naked, the bones thin and soft; opercular bones weakly serrate; mouth large, terminal, the upper jaw extremely protrusile; maxilla widely expanded posteriorly, and mostly exposed when mouth is closed; no supramaxilla; jaws with 1 or 2 rows of small, slender, conical teeth; vomer with a few short stout teeth;gill rakers (including rudiments) 2 on upper limb, 8 on lower limb.Eye diameter about 1/3 head length and slightly less than snout length.Branchiostegal rays 7.Dorsal fin divided, with 8 slender spines and 26 to 30 soft rays; anal fin with 1 minute spine and 30 to 32 soft rays; dorsal-, anal-, and pectoral-fin rays un- branched; caudal fin forked, with 11 principal rays and 9 branched rays; pectoral fin with 15 or 16 rays, shorter than eye diameter; pelvic fins with 1 unbranched and 5 or 6 branched soft rays, but no spine, fin origin posterior to a vertical at pectoral-fin base. Scales moderate in size, weakly ctenoid, and deciduous; 2 lateral lines originating on body at upper end of operculum and running posteriorly about 4 scale rows apart, gradually converging to form a single line on caudal peduncle. Caudal peduncle stout, the least depth about equal to its length and slightly less than eye diameter.Vertebrae 34.Colour: body reddish or silvery; large black blotch on anterior margin of dorsal fin. -

Climate Change Impacts on the Distribution of Coastal Lobsters

Marine Biology (2018) 165:186 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-018-3441-9 SHORT NOTE Climate change impacts on the distribution of coastal lobsters Joana Boavida‑Portugal1,2 · Rui Rosa2 · Ricardo Calado3 · Maria Pinto4 · Inês Boavida‑Portugal5 · Miguel B. Araújo1,6,7 · François Guilhaumon8,9 Received: 17 January 2018 / Accepted: 26 October 2018 / Published online: 16 November 2018 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Coastal lobsters support important fsheries all over the world, but there is evidence that climate-induced changes may jeopardize some stocks. Here we present the frst global forecasts of changes in coastal lobster species distribution under climate change, using an ensemble of ecological niche models (ENMs). Global changes in richness were projected for 125 coastal lobster species for the end of the century, using a stabilization scenario (4.5 RCP). We compared projected changes in diversity with lobster fsheries data and found that losses in suitable habitat for coastal lobster species were mainly projected in areas with high commercial fshing interest, with species projected to contract their climatic envelope between 40 and 100%. Higher losses of spiny lobsters are projected in the coasts of wider Caribbean/Brazil, eastern Africa and Indo-Pacifc region, areas with several directed fsheries and aquacultures, while clawed lobsters are projected to shifts their envelope to northern latitudes likely afecting the North European, North American and Canadian fsheries. Fisheries represent an important resource for local and global economies and understanding how they might be afected by climate change scenarios is paramount when developing specifc or regional management strategies. -

Global Drivers of Diversification in a Marine Species Complex 2 3 Catarina N.S

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.13.874883; this version posted December 15, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Global drivers of diversification in a marine species complex 2 3 Catarina N.S. Silva1, Nicholas P. Murphy2, James J. Bell3, Bridget S. Green4, Guy Duhamel5, Andrew C. 4 Cockcroft6, Cristián E. Hernández7, Jan M. Strugnell1, 2 5 6 7 1 Centre of Sustainable Tropical Fisheries and AQuaculture, James Cook University, Townsville, Qld 4810, 8 Australia 9 2 Department of Ecology, Environment & Evolution, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Vic 3086, Australia 10 3 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, 6140, New Zealand 11 4 Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS 7001, Australia 12 5 Département Adaptations du Vivant, BOREA, MNHN, Paris, 75005, France 13 6 Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Cape Town, 8012, South Africa 14 7 Departamento de Zoología, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas, Universidad de Concepción, 15 Casilla 160C, Concepción, Chile 16 17 18 Abstract 19 Investigating historical gene flow in species complexes can indicate how environmental and reproductive 20 barriers shape genome divergence before speciation. The processes influencing species diversification under 21 environmental change remain one of the central focal points of evolutionary biology, particularly for marine 22 organisms with high dispersal potential. We investigated genome-wide divergence, introgression patterns and 23 inferred demographic history between species pairs of all extant rock lobster species (Jasus spp.), a complex 24 with long larval duration, that has populated continental shelf and seamount habitats around the globe at 25 approximately 40oS. -

Crustacea, Malacostraca, Bathynellacea, 16S Rdna

Contributions to Zoology, 71 (4) 123-129 (2002) SPB AcademicPublishing bv. The Hague A note on the systematic position of the Bathynellacea (Crustacea, Malacostraca) using molecular evidence Ana+Isabel Camacho Isabel Rey²,Beatriz+A. Dorda Annie ³ ², Machordom Antonio+G. Valdecasas ¹ ³, 'Museo Naturales Nacional de Ciencias (CSIC). Dpto. Biodiversidady Biologia Evolutiva. C/ Jose Gutierrez Ahascal 28006- 2 2, Madrid. Spain, [email protected]; Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC), de Colecciones. Jose Gutierrez 3 Dpto. C/ Ahascal 2, 28006- Madrid; Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC), Dpto. Biodiversidady Biologia Evolutiva. C/ Jose Gutierrez Ahascal 2, 28006- Madrid. Keywords: Systematics, Crustacea, Malacostraca, Bathynellacea, 16S rDNA. lar, is the Abstract usually homogeneous amongst special- ists. The traditional of way working is to use the latest information or the latest Molecular data for the 16S of ba- hypothesis mt rDNA gene fragment a published in order to thynellacean is here presented for the first time and used to select those views that are going to be the of within the analyze relationship the group crustacean class compared. However, it must be universal that where Malacostraca Two (Arthropoda, Bathynellacea). contrasting there is more than one taxonomist working on a views have classified the bathynelids as being cither within the there will be group not a single hypothesis or in- order Syncarida or in a separate super-order Podophallocarida of the How terpretation descent. or small based group’s big belonging to the infra-class Eonomostraca, a disagreement are these irrelevant on debates internal The discrepancies and does it not mainly over external and morphology. -

Provisional Agenda*

CBD Distr. GENERAL UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/16/INF/6 11 April 2012 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH SUBSIDIARY BODY ON SCIENTIFIC, TECHNICAL AND TECHNOLOGICAL ADVICE Sixteenth meeting Montreal, 30 April-5 May 2012 Item 6.1 of the provisional agenda* REPORT OF THE WESTERN SOUTH PACIFIC REGIONAL WORKSHOP TO FACILITATE THE DESCRIPTION OF ECOLOGICALLY OR BIOLOGICALLY SIGNIFICANT MARINE AREAS INTRODUCTION 1. At its tenth meeting, the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP 10) requested the Executive Secretary to work with Parties and other Governments as well as competent organizations and regional initiatives, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), regional seas conventions and action plans, and, where appropriate, regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs), with regard to fisheries management, to organize, including the setting of terms of reference, a series of regional workshops, with a primary objective to facilitate the description of ecologically or biologically significant marine areas through the application of scientific criteria in annex I to decision IX/20 as well as other relevant compatible and complementary nationally and intergovernmentally agreed scientific criteria, as well as the scientific guidance on the identification of marine areas beyond national jurisdiction, which meet the scientific criteria in annex I to decision IX/20 (paragraph 36, decision X/29). 2. In the same decision (paragraph 41), the Conference of the Parties requested that the Executive Secretary make available the scientific and technical data and information and results collated through the workshops referred to above to participating Parties, other Governments, intergovernmental agencies and the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA) for their use according to their competencies. -

A Preliminary Assessment of the Deepwater Benthic Communities of the Great Australian Bight Marine Park

MMaarriinnee EEnnvviirroonnmmeenntt && EEccoollooggyy A preliminary assessment of the deepwater benthic communities of the Great Australian Bight Marine Park David R. Currie and Shirley J. Sorokin SARDI Publication No. F2011/000526-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 592 SARDI Aquatic Sciences 2 Hamra Avenue West Beach SA 5024 December 2011 Report to the South Australian Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the Commonwealth Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities A preliminary assessment of the deepwater benthic communities of the Great Australian Bight Marine Park Report to the South Australian Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the Commonwealth Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities David R. Currie and Shirley J. Sorokin SARDI Publication No. F2011/000526-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 592 December 2011 Currie, D.R. and Sorokin, S.J. (2011) Deepwater benthos of the GABMP This Publication may be cited as: Currie, D.R. and Sorokin, S.J (2011). A preliminary assessment of the deepwater benthic communities of the Great Australian Bight Marine Park. Report to the South Australian Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the Commonwealth Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2011/000526- 1. SARDI Research Report Series No. 592. 61pp. South Australian Research and Development Institute SARDI Aquatic Sciences 2 Hamra Avenue West Beach SA 5024 Telephone: (08) 8207 5400 Facsimile: (08) 8207 5406 http://www.sardi.sa.gov.au DISCLAIMER The authors warrant that they have taken all reasonable care in producing this report. -

Dunn (2013) Ecosystem Impacts of Orange Roughy Fisheries

Please do not cite without prior reference to the author ECOSYSTEM IMPACTS OF ORANGE ROUGHY FISHERIES Dr Matthew Dunn School of Biological Sciences Victoria University of Wellington [email protected] July 2013 Summary This document provides background information and a perspective on the ecosystem impact of orange roughy fishing. It is not comprehensive, but intended to be indicative of current knowledge and understanding. My objective was to consider how we might best monitor the orange roughy ecosystem for signs of significant or informative change in function, and in its ability to maintain ecosystem services. I have structured the text into sections; (1) the orange roughy ecosystem, (2) ecosystem outcome, (3) ecosystem management, and (4) ecosystem monitoring. My focus is on (1) and (2). Within these first two sections, I have kept a summary of key existing knowledge separate from a discussion of theory and research. The latter may include further detail on existing research and data sets, other pertinent findings, and ideas for research which may improve our understanding. Orange roughy fishing has two main impacts. The first is capture of target species and by‐catch, and the second is damage to the seabed by bottom trawls (including incidental mortality). I have tended to focus on the ecosystem impacts of the former. This is because of my expertise, and because bottom trawl impacts may be reduced, minimised or mitigated through reduction in the trawl footprint, whereas a Bmsy objective does, by definition, require a persistent and substantial reduction in the biomass of the target species (and potentially the closely associated by‐catch). -

SPRFMO4 SWG 11 Species Profile

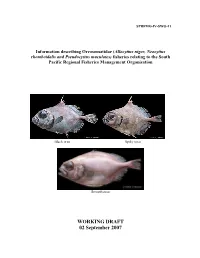

SPRFMO-IV-SWG-11 Information describing Oreosomatidae (Allocyttus niger, Neocyttus rhomboidalis and Pseudocyttus maculates) fisheries relating to the South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation Black oreo Spiky oreo Smooth oreo WORKING DRAFT 02 September 2007 1 Overview...........................................................................................................................2 2 Taxonomy.........................................................................................................................3 2.1 Phylum......................................................................................................................3 2.2 Class..........................................................................................................................3 2.3 Order.........................................................................................................................3 2.4 Family.......................................................................................................................3 2.5 Genus and species......................................................................................................3 2.6 Scientific synonyms...................................................................................................3 2.7 Common names.........................................................................................................3 2.8 Molecular (DNA or biochemical) bar coding..............................................................3 3 Species Characteristics.....................................................................................................4 -

Orange Roughy (Hoplostethus Atlanticus)

Seafood Watch Seafood Report Orange Roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) Final Report March 28, 2003 Melissa M Stevens Fisheries Research Analyst Monterey Bay Aquarium Orange_Roughy_SFW _MS_Final.doc 28 March 2003 About Seafood Watch® and the Seafood Reports Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch® program evaluates the ecological sustainability of wild-caught and farmed seafood commonly found in the United States marketplace. Seafood Watch defines sustainable seafood as species, whether fished or farmed, that can exist into the long-term by maintaining or increasing stock abundance and conserving the structure, function, biodiversity and productivity of the surrounding ecosystem. Seafood Watch® makes its science- based recommendations available to the public in the form of regional pocket guides that can be downloaded from the web (www.montereybayaquarium.org) or obtained from the program by emailing [email protected]. The program’s goals are to raise awareness of important ocean conservation issues and to shift the buying habits of consumers, restaurateurs and other seafood purveyors to support sustainable fishing and aquaculture practices. Each sustainability recommendation on the regional pocket guides is supported by a Seafood Report. Each report synthesizes and analyzes the most current ecological, fisheries and ecosystem science on a species then evaluates this information against the program’s conservation ethic to arrive at a recommendation of “Best Choices”, “Proceed with Caution” or “Avoid”. In producing the Seafood Reports, Seafood Watch seeks out research published in academic, peer-reviewed journals whenever possible. Other sources of information include government technical publications, fishery management plans and supporting documents, and other scientific reviews of ecological sustainability. Seafood Watch Fishery Analysts also communicate regularly with ecologists, fisheries and aquaculture scientists, and members of industry and conservation organizations when evaluating fisheries and aquaculture practices.