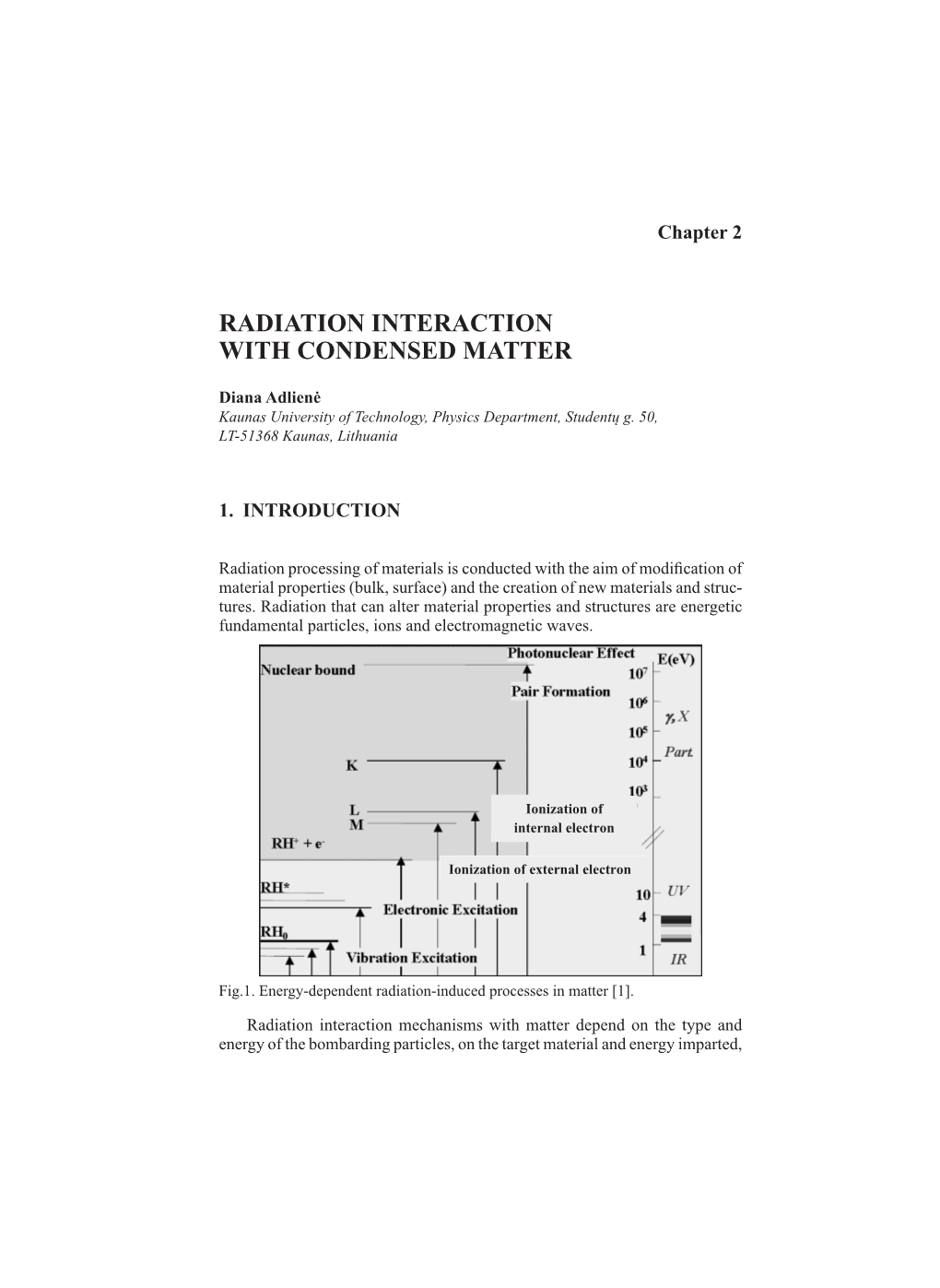

Radiation Interaction with Condensed Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part B. Radiation Sources Radiation Safety

Part B. Radiation sources Radiation Safety 1. Interaction of electrons-e with the matter −31 me = 9.11×10 kg ; E = m ec2 = 0.511 MeV; qe = -e 2. Interaction of photons-γ with the matter mγ = 0 kg ; E γ = 0 eV; q γ = 0 3. Interaction of neutrons-n with the matter −27 mn = 1.68 × 10 kg ; En = 939.57 MeV; qn = 0 4. Interaction of protons-p with the matter −27 mp = 1.67 × 10 kg ; Ep = 938.27 MeV; qp = +e Note: for any nucleus A: mass number – nucleons number A = Z + N Z: atomic number – proton (charge) number N: neutron number 1 / 35 1. Interaction of electrons with the matter Radiation Safety The physical processes: 1. Ionization losses inelastic collisions with orbital electrons 2. Bremsstrahlung losses inelastic collisions with atomic nuclei 3. Rutherford scattering elastic collisions with atomic nuclei Positrons at nearly rest energy: annihilation emission of two 511 keV photons 2 / 35 1. Interaction of electrons with1.E+02 the matter Radiation Safety ) 1.E+03 -1 Graphite – Z = 6 .g 2 1.E+01 ) Lead – Z = 82 -1 .g 2 1.E+02 1.E+00 1.E+01 1.E-01 1.E+00 collision 1.E-02 radiative collision 1.E-01 stopping pow er (MeV.cm total radiative 1.E-03 stopping pow er (MeV.cm total 1.E-02 1.E-01 1.E+00 1.E+01 1.E+02 1.E+03 1.E-02 energy (MeV) 1.E-02 1.E-01 1.E+00 1.E+01 1.E+02 1.E+03 Electrons – stopping power 1.E+02 energy (MeV) S 1 dE ) === -1 Copper – Z = 29 ρρρ ρρρ dl .g 2 1.E+01 S 1 dE 1 dE === +++ ρρρ ρρρ dl coll ρρρ dl rad 1 dE 1.E+00 : mass stopping power (MeV.cm 2 g. -

The Basic Interactions Between Photons and Charged Particles With

Outline Chapter 6 The Basic Interactions between • Photon interactions Photons and Charged Particles – Photoelectric effect – Compton scattering with Matter – Pair productions Radiation Dosimetry I – Coherent scattering • Charged particle interactions – Stopping power and range Text: H.E Johns and J.R. Cunningham, The – Bremsstrahlung interaction th physics of radiology, 4 ed. – Bragg peak http://www.utoledo.edu/med/depts/radther Photon interactions Photoelectric effect • Collision between a photon and an • With energy deposition atom results in ejection of a bound – Photoelectric effect electron – Compton scattering • The photon disappears and is replaced by an electron ejected from the atom • No energy deposition in classical Thomson treatment with kinetic energy KE = hν − Eb – Pair production (above the threshold of 1.02 MeV) • Highest probability if the photon – Photo-nuclear interactions for higher energies energy is just above the binding energy (above 10 MeV) of the electron (absorption edge) • Additional energy may be deposited • Without energy deposition locally by Auger electrons and/or – Coherent scattering Photoelectric mass attenuation coefficients fluorescence photons of lead and soft tissue as a function of photon energy. K and L-absorption edges are shown for lead Thomson scattering Photoelectric effect (classical treatment) • Electron tends to be ejected • Elastic scattering of photon (EM wave) on free electron o at 90 for low energy • Electron is accelerated by EM wave and radiates a wave photons, and approaching • No -

Particles and Deep Inelastic Scattering

Heidi Schellman Northwestern Particles and Deep Inelastic Scattering Heidi Schellman Northwestern University HUGS - JLab - June 2010 June 2010 HUGS 1 Heidi Schellman Northwestern k’ k q P P’ A generic scatter of a lepton off of some target. kµ and k0µ are the 4-momenta of the lepton and P µ and P 0µ indicate the target and the final state of the target, which may consist of many particles. qµ = kµ − k0µ is the 4-momentum transfer to the target. June 2010 HUGS 2 Heidi Schellman Northwestern Lorentz invariants k’ k q P P’ 2 2 02 2 2 2 02 2 2 2 The 5 invariant masses k = m` , k = m`0, P = M , P ≡ W , q ≡ −Q are invariants. In addition you can define 3 Mandelstam variables: s = (k + P )2, t = (k − k0)2 and u = (P − k0)2. 2 2 2 2 s + t + u = m` + M + m`0 + W . There are also handy variables ν = (p · q)=M , x = Q2=2Mµ and y = (p · q)=(p · k). June 2010 HUGS 3 Heidi Schellman Northwestern In the lab frame k’ k θ q M P’ The beam k is going in the z direction. Confine the scatter to the x − z plane. µ k = (Ek; 0; 0; k) P µ = (M; 0; 0; 0) 0µ 0 0 0 k = (Ek; k sin θ; 0; k cos θ) qµ = kµ − k0µ June 2010 HUGS 4 Heidi Schellman Northwestern In the lab frame k’ k θ q M P’ 2 2 2 s = ECM = 2EkM + M − m ! 2EkM 2 0 0 2 02 0 t = −Q = −2EkEk + 2kk cos θ + mk + mk ! −2kk (1 − cos θ) 0 ν = (p · q)=M = Ek − Ek energy transfer to target 0 y = (p · q)=(p · k) = (Ek − Ek)=Ek the inelasticity P 02 = W 2 = 2Mν + M 2 − Q2 invariant mass of P 0µ June 2010 HUGS 5 Heidi Schellman Northwestern In the CM frame k’ k q P P’ The beam k is going in the z direction. -

The Effects of Elastic Scattering in Neutral Atom Transport D

The effects of elastic scattering in neutral atom transport D. N. Ruzic Citation: Phys. Fluids B 5, 3140 (1993); doi: 10.1063/1.860651 View online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.860651 View Table of Contents: http://pop.aip.org/resource/1/PFBPEI/v5/i9 Published by the American Institute of Physics. Related Articles Dissociation mechanisms of excited CH3X (X = Cl, Br, and I) formed via high-energy electron transfer using alkali metal targets J. Chem. Phys. 137, 184308 (2012) Efficient method for quantum calculations of molecule-molecule scattering properties in a magnetic field J. Chem. Phys. 137, 024103 (2012) Scattering resonances in slow NH3–He collisions J. Chem. Phys. 136, 074301 (2012) Accurate time dependent wave packet calculations for the N + OH reaction J. Chem. Phys. 135, 104307 (2011) The k-j-j′ vector correlation in inelastic and reactive scattering J. Chem. Phys. 135, 084305 (2011) Additional information on Phys. Fluids B Journal Homepage: http://pop.aip.org/ Journal Information: http://pop.aip.org/about/about_the_journal Top downloads: http://pop.aip.org/features/most_downloaded Information for Authors: http://pop.aip.org/authors Downloaded 23 Dec 2012 to 192.17.144.173. Redistribution subject to AIP license or copyright; see http://pop.aip.org/about/rights_and_permissions The effects of elastic scattering in neutral atom transport D. N. Ruzic University of Illinois, 103South Goodwin Avenue, Urbana Illinois 61801 (Received 14 December 1992; accepted21 May 1993) Neutral atom elastic collisions are one of the dominant interactions in the edge of a high recycling diverted plasma. Starting from the quantum interatomic potentials, the scattering functions are derived for H on H ‘, H on Hz, and He on Hz in the energy range of 0. -

Elastic Scattering, Fusion, and Breakup of Light Exotic Nuclei

Eur. Phys. J. A (2016) 52: 123 THE EUROPEAN DOI 10.1140/epja/i2016-16123-1 PHYSICAL JOURNAL A Review Elastic scattering, fusion, and breakup of light exotic nuclei J.J. Kolata1,a, V. Guimar˜aes2, and E.F. Aguilera3 1 Physics Department, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 46556-5670, USA 2 Instituto de F`ısica,Universidade de S˜aoPaulo, Rua do Mat˜ao,1371, 05508-090, S˜aoPaulo, SP, Brazil 3 Departamento de Aceleradores, Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Nucleares, Apartado Postal 18-1027, C´odigoPostal 11801, M´exico, Distrito Federal, Mexico Received: 18 February 2016 Published online: 10 May 2016 c The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Communicated by N. Alamanos Abstract. The present status of fusion reactions involving light (A<20) radioactive projectiles at energies around the Coulomb barrier (E<10 MeV per nucleon) is reviewed, emphasizing measurements made within the last decade. Data on elastic scattering (providing total reaction cross section information) and breakup channels for the involved systems, demonstrating the relationship between these and the fusion channel, are also reviewed. Similarities and differences in the behavior of fusion and total reaction cross section data concerning halo nuclei, weakly-bound but less exotic projectiles, and strongly-bound systems are discussed. One difference in the behavior of fusion excitation functions near the Coulomb barrier seems to emerge between neutron-halo and proton-halo systems. The role of charge has been investigated by comparing the fusion excitation functions, properly scaled, for different neutron- and proton-rich systems. Possible physical explanations for the observed differences are also reviewed. -

Status of Electron Transport Cross Sections

A11102 mob2fl NBS PUBLICATIONS AlllOb MOflOAb NBSIR 82-2572 Status of Electron Transport Cross Sections U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Bureau of Standards Washington, DC 20234 September 1 982 Prepared for: Office of Naval Research Arlington, Virginia 22217 Space Science Data Center NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 20771 Office of Health and Environmental Research Department of Energy jyj Washington, DC 20545 c.2 '»AT10*AL. BURKAU OF »TAMTARJ»a LIBRARY SEP 2 0 1982 NBSIR 82-2572 STATUS OF ELECTRON TRANSPORT CROSS SECTIONS S. M. Seltzer and M. J. Berger U S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Bureau of Standards Washington, DC 20234 September 1 982 Prepared for: Office of Naval Research Arlington, Virginia 22217 Space Science Data Center NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 20771 Office of Health and Environmental Research Department of Energy Washington, DC 20545 (A Q * U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, Malcolm Baldrige, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS, Ernest Ambler, Director u r ju ' ^ l. .• .. w > - H *+ Status of Electron Transport Cross Sections Stephen M. Seltzer and Martin J. Berger National Bureau of Standards Washington, D.C. 20234 This report describes recent developments and improvements pertaining to cross sections for electron-photon transport calculations. The topics discussed include: (1) electron stopping power (mean excitation energies, density-effect correction); (2) bremsstrahlung production by electrons (radiative stopping power, spectrum of emitted photons); (3) elastic scattering of electrons by atoms; (4) electron-impact ionization of atoms. Key words: bremsstrahlung; cross sections; elastic scattering; electron- impact ionization; electrons; photons; stopping power; transport. Summary of a paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Nuclear Society, June 7-11, 1982, Los Angeles, California. -

Part Fourteen Kinematics of Elastic Neutron Scattering

22.05 Reactor Physics - Part Fourteen Kinematics of Elastic Neutron Scattering 1. Multi-Group Theory: The next method that we will study for reactor analysis and design is multi-group theory. This approach entails dividing the range of possible neutron energies into small regions, ΔEi and then defining a group cross-section that is averaged over each energy group i. Neutrons enter each group as the result of either fission (recall the distribution function for fission neutrons) or scattering. Accordingly, we need a thorough understanding of the scattering process before proceeding. 2. Types of Scattering: Fission neutrons are born at high energies (>1 MeV). However, the fission reaction is best sustained by neutrons that are at thermal energies with “thermal” defined as 0.025 eV. It is only at these low energies that the cross-section of U-235 is appreciable. So, a major challenge in reactor design is to moderate or slow down the fission neutrons. This can be achieved via either elastic or inelastic scattering: a) Elastic Scatter: Kinetic energy is conserved. This mechanism works well for neutrons with energies 10 MeV or below. Light nuclei, ones with low mass number, are best because the lighter the nucleus, the larger the fraction of energy lost per collision. b) Inelastic Scatter: The neutron forms an excited state with the target nucleus. This requires energy and the process is only effective for neutron energies above 0.1 MeV. Collisions with iron nuclei are the preferred approach. Neutron scattering is important in two aspects of nuclear engineering. One is the aforementioned neutron moderation. -

ELEMENTARY PARTICLES in PHYSICS 1 Elementary Particles in Physics S

ELEMENTARY PARTICLES IN PHYSICS 1 Elementary Particles in Physics S. Gasiorowicz and P. Langacker Elementary-particle physics deals with the fundamental constituents of mat- ter and their interactions. In the past several decades an enormous amount of experimental information has been accumulated, and many patterns and sys- tematic features have been observed. Highly successful mathematical theories of the electromagnetic, weak, and strong interactions have been devised and tested. These theories, which are collectively known as the standard model, are almost certainly the correct description of Nature, to first approximation, down to a distance scale 1/1000th the size of the atomic nucleus. There are also spec- ulative but encouraging developments in the attempt to unify these interactions into a simple underlying framework, and even to incorporate quantum gravity in a parameter-free “theory of everything.” In this article we shall attempt to highlight the ways in which information has been organized, and to sketch the outlines of the standard model and its possible extensions. Classification of Particles The particles that have been identified in high-energy experiments fall into dis- tinct classes. There are the leptons (see Electron, Leptons, Neutrino, Muonium), 1 all of which have spin 2 . They may be charged or neutral. The charged lep- tons have electromagnetic as well as weak interactions; the neutral ones only interact weakly. There are three well-defined lepton pairs, the electron (e−) and − the electron neutrino (νe), the muon (µ ) and the muon neutrino (νµ), and the (much heavier) charged lepton, the tau (τ), and its tau neutrino (ντ ). These particles all have antiparticles, in accordance with the predictions of relativistic quantum mechanics (see CPT Theorem). -

Simulation of Transmission and Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopic Images Considering Elastic and Thermal Diffuse Scattering

Scanning Microscopy Vol. 11, 1997 (Pages 277-286) 0891-7035/97$5.00+.25 Scanning Microscopy International, Chicago (AMFSimulation O’Hare), of TEM IL 60666 and STEM USA images SIMULATION OF TRANSMISSION AND SCANNING TRANSMISSION ELECTRON MICROSCOPIC IMAGES CONSIDERING ELASTIC AND THERMAL DIFFUSE SCATTERING C. Dinges and H. Rose* Institute of Applied Physics, Darmstadt University of Technology, Darmstadt, Germany Abstract Introduction A reliable image simulation procedure for transmis- In the past, several attempts have been made to sion (TEM) and scanning transmission (STEM) electron include thermal diffuse scattering and inelastic scattering microscopic images must take into account plural elastic into the theory of image formation in electron microscopy. scattering, inelastic scattering and thermal diffuse scattering. The approaches of Rose (1984), Wang (1995) and Dinges et The intensity of the simulated images depends strongly on al. (1995) are based on the multislice formalism (Cowley and the elastic scattering amplitude and the models chosen to Moodie, 1957) which allows the calculation of inelastically describe inelastic and thermal diffuse scattering. Our filtered images for transmission (TEM) and scanning improved image simulation procedure utilizes the approxima- transmission (STEM) electron microscopy. Allen and tion proposed by Weickenmeier and Kohl for the elastic Roussow (1993) proposed an ansatz using the Bloch wave scattering amplitude instead of the Doyle-Turner approx- formalism. imation. Thermal diffuse scattering is treated in terms of the Thermal diffuse scattering has been included into Einstein model. In this paper, simulated TEM diffraction an image simulation procedure for the first time by Xu et al. patterns and high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) STEM (1990). -

Elastic Scattering and Reaction Mechanisms of the Halo Nucleus 11Be Around the Coulomb Barrier

week ending PRL 105, 022701 (2010) PHYSICAL REVIEW LETTERS 9 JULY 2010 Elastic Scattering and Reaction Mechanisms of the Halo Nucleus 11Be around the Coulomb Barrier A. Di Pietro,1 G. Randisi,1,2,* V. Scuderi,1,2 L. Acosta,3 F. Amorini,1,2 M. J. G. Borge,4 P. Figuera,1 M. Fisichella,1,2 L. M. Fraile,5,† J. Gomez-Camacho,6 H. Jeppesen,5,‡ M. Lattuada,1,2 I. Martel,3 M. Milin,7 A. Musumarra,1,8 M. Papa,1 M. G. Pellegriti,1,2 F. Perez-Bernal,3 R. Raabe,9 F. Rizzo,1,2 D. Santonocito,1 G. Scalia,1,2 O. Tengblad,4 D. Torresi,1,2 A. Maira Vidal,4 D. Voulot,5 F. Wenander,5 and M. Zadro10 1INFN–Laboratori Nazionali del Sud and Sezione di Catania, Catania, Italy 2Dipartimento di Fisica ed Astronomia, Universita´ di Catania, Catania, Italy 3Departamento de Fisica Aplicada, Universidad de Huelva, Huelva, Spain 4Instituto de Estructura de la Materia CSIC, Madrid, Spain 5ISOLDE, CERN, CH-1211 Geneva 23, Switzerland 6Departamento de Fisica Atomica Molecular Nuclear, Universidad de Sevilla and Centro Nacional de Aceleradores, Sevilla, Spain 7Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia 8Dipartimento di Metodologie Fisiche e Chimiche per l’Ingegneria, Universita´ di Catania, Catania, Italy 9Instituut voor Kern-en Stralingsfysica, Katholieke Universiteit, Leuven, Belgium 10Division of Experimental Physics, Ru‘er Bosˇkovic´ Institute, Zagreb, Croatia (Received 7 March 2010; published 6 July 2010) Collisions induced by 9;10;11Be on a 64Zn target at the same c.m. energy were studied. -

Nuclear Reactions (Theory)

Outline Overview of Nuclear Reactions Elastic Cross Sections Reactions Theory I Ian Thompson Nuclear Theory and Modeling Group Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory [email protected] LLNL-PRES-491271 Ian Thompson Reactions Theory I Elastic Cross Sections Phase Shifts from Potentials Integral Expressions Outline Overview of Nuclear Reactions Elastic Cross Sections Overview of Nuclear Reactions Compound and Direct Reactions Types of direct reactions Ian Thompson Reactions Theory I Outline Overview of Nuclear Reactions Elastic Cross Sections Overview of Nuclear Reactions Compound and Direct Reactions Types of direct reactions Elastic Cross Sections Phase Shifts from Potentials Integral Expressions Ian Thompson Reactions Theory I Outline Overview of Nuclear Reactions Types of direct reactions Elastic Cross Sections Classification by Outcome 1. Elastic scattering: projectile and target stay in their g.s. 2. Inelastic scattering: projectile or target left in excited state 3. Transfer reaction: 1 or more nucleons moved to the other nucleus 4. Fragmentation/Breakup/Knockout: 3 or more nuclei/nucleons in the final state 5. Charge Exchange: A is constant but Z (charge) varies, e.g. by pion exchange 6. Multistep Processes: intermediate steps can be any of the above (`virtual' rather than `real') Ian Thompson Reactions Theory I Outline Overview of Nuclear Reactions Types of direct reactions Elastic Cross Sections 7. Deep inelastic collisions: Highly excited states produced 8. Fusion: Nuclei stick together 9. Fusion-evaporation: fusion followed by particle-evaporation and/or gamma emission 10. Fusion-fission: fusion followed by fission The first 6 processes are Direct Reactions (DI) The last 3 processes give a Compound Nucleus (CN). Ian Thompson Reactions Theory I Outline Overview of Nuclear Reactions Types of direct reactions Elastic Cross Sections Compound and Direct Reactions So when two nuclei collide there are 2 types of reactions: 1. -

Electron Microscopy I

Characterization of Catalysts and Surfaces Characterization Techniques in Heterogeneous Catalysis Electron Microscopy I • Introduction • Properties of electrons • Electron-matter interactions and their applications Frank Krumeich [email protected] www.microscopy.ethz.ch How do crystals look like? Shape? SEM images of zeolithes (left) and metal organic frameworks (MOF, right) Examples: electron microscopy for catalyst characterization 1 How does the Structure of catalysts look like? Size of the particles? HRTEM image of an Ag BF-STEM image of Pt particles particle on ZnO on CeO2 Examples: electron microscopy for catalyst characterization Pd and Pt supported on alumina: Size of the particles? Alloy or separated? STEM + EDXS: Point Analyses Al C O Pt Pd Cu Pt Pt Al C HAADF-STEM image O Pt Cu Pd Pt Pt Examples: electron microscopy for catalyst characterization 2 Electron Microscopy Methods (Selection) STEM Electron diffraction HRTEM X-ray spectroscopy SEM Discovery of the Electron 1897 J. J. Thomson: Experiments with cathode rays hypotheses: (i) Cathode rays are charged particles ("corpuscles"). (ii) Corpuscles are constituents of the Joseph John Thomson (1856-1940) atom. Nobel prize 1906 Electron 3 Properties of Electrons Dualism wave-particle De Broglie (1924): = h/p = h/mv : wavelength; h: Planck constant; p: momentum 2 Accelerated electrons: E = eV = m0v /2 V: acceleration voltage e / m0 / v: charge / rest mass / velocity of the electron 1/2 p = m0v = (2m0eV) 1/2 1/2 = h / (2m0eV) ( 1.22 / V nm) Relativistic effects: 2 1/2