Part Fourteen Kinematics of Elastic Neutron Scattering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10. Collisions • Use Conservation of Momentum and Energy and The

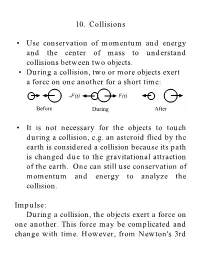

10. Collisions • Use conservation of momentum and energy and the center of mass to understand collisions between two objects. • During a collision, two or more objects exert a force on one another for a short time: -F(t) F(t) Before During After • It is not necessary for the objects to touch during a collision, e.g. an asteroid flied by the earth is considered a collision because its path is changed due to the gravitational attraction of the earth. One can still use conservation of momentum and energy to analyze the collision. Impulse: During a collision, the objects exert a force on one another. This force may be complicated and change with time. However, from Newton's 3rd Law, the two objects must exert an equal and opposite force on one another. F(t) t ti tf Dt From Newton'sr 2nd Law: dp r = F (t) dt r r dp = F (t)dt r r r r tf p f - pi = Dp = ò F (t)dt ti The change in the momentum is defined as the impulse of the collision. • Impulse is a vector quantity. Impulse-Linear Momentum Theorem: In a collision, the impulse on an object is equal to the change in momentum: r r J = Dp Conservation of Linear Momentum: In a system of two or more particles that are colliding, the forces that these objects exert on one another are internal forces. These internal forces cannot change the momentum of the system. Only an external force can change the momentum. The linear momentum of a closed isolated system is conserved during a collision of objects within the system. -

The Physics of a Car Collision by Andrew Zimmerman Jones, Thoughtco.Com on 09.10.19 Word Count 947 Level MAX

The physics of a car collision By Andrew Zimmerman Jones, ThoughtCo.com on 09.10.19 Word Count 947 Level MAX Image 1. A crash test dummy sits inside a Toyota Corolla during the 2017 North American International Auto Show in Detroit, Michigan. Crash test dummies are used to predict the injuries that a human might sustain in a car crash. Photo by: Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images During a car crash, energy is transferred from the vehicle to whatever it hits, be it another vehicle or a stationary object. This transfer of energy, depending on variables that alter states of motion, can cause injuries and damage cars and property. The object that was struck will either absorb the energy thrust upon it or possibly transfer that energy back to the vehicle that struck it. Focusing on the distinction between force and energy can help explain the physics involved. Force: Colliding With A Wall Car crashes are clear examples of how Newton's Laws of Motion work. His first law of motion, also referred to as the law of inertia, asserts that an object in motion will stay in motion unless an external force acts upon it. Conversely, if an object is at rest, it will remain at rest until an unbalanced force acts upon it. Consider a situation in which car A collides with a static, unbreakable wall. The situation begins with car A traveling at a velocity (v) and, upon colliding with the wall, ending with a velocity of 0. The force of this situation is defined by Newton's second law of motion, which uses the equation of This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. -

Part B. Radiation Sources Radiation Safety

Part B. Radiation sources Radiation Safety 1. Interaction of electrons-e with the matter −31 me = 9.11×10 kg ; E = m ec2 = 0.511 MeV; qe = -e 2. Interaction of photons-γ with the matter mγ = 0 kg ; E γ = 0 eV; q γ = 0 3. Interaction of neutrons-n with the matter −27 mn = 1.68 × 10 kg ; En = 939.57 MeV; qn = 0 4. Interaction of protons-p with the matter −27 mp = 1.67 × 10 kg ; Ep = 938.27 MeV; qp = +e Note: for any nucleus A: mass number – nucleons number A = Z + N Z: atomic number – proton (charge) number N: neutron number 1 / 35 1. Interaction of electrons with the matter Radiation Safety The physical processes: 1. Ionization losses inelastic collisions with orbital electrons 2. Bremsstrahlung losses inelastic collisions with atomic nuclei 3. Rutherford scattering elastic collisions with atomic nuclei Positrons at nearly rest energy: annihilation emission of two 511 keV photons 2 / 35 1. Interaction of electrons with1.E+02 the matter Radiation Safety ) 1.E+03 -1 Graphite – Z = 6 .g 2 1.E+01 ) Lead – Z = 82 -1 .g 2 1.E+02 1.E+00 1.E+01 1.E-01 1.E+00 collision 1.E-02 radiative collision 1.E-01 stopping pow er (MeV.cm total radiative 1.E-03 stopping pow er (MeV.cm total 1.E-02 1.E-01 1.E+00 1.E+01 1.E+02 1.E+03 1.E-02 energy (MeV) 1.E-02 1.E-01 1.E+00 1.E+01 1.E+02 1.E+03 Electrons – stopping power 1.E+02 energy (MeV) S 1 dE ) === -1 Copper – Z = 29 ρρρ ρρρ dl .g 2 1.E+01 S 1 dE 1 dE === +++ ρρρ ρρρ dl coll ρρρ dl rad 1 dE 1.E+00 : mass stopping power (MeV.cm 2 g. -

The Basic Interactions Between Photons and Charged Particles With

Outline Chapter 6 The Basic Interactions between • Photon interactions Photons and Charged Particles – Photoelectric effect – Compton scattering with Matter – Pair productions Radiation Dosimetry I – Coherent scattering • Charged particle interactions – Stopping power and range Text: H.E Johns and J.R. Cunningham, The – Bremsstrahlung interaction th physics of radiology, 4 ed. – Bragg peak http://www.utoledo.edu/med/depts/radther Photon interactions Photoelectric effect • Collision between a photon and an • With energy deposition atom results in ejection of a bound – Photoelectric effect electron – Compton scattering • The photon disappears and is replaced by an electron ejected from the atom • No energy deposition in classical Thomson treatment with kinetic energy KE = hν − Eb – Pair production (above the threshold of 1.02 MeV) • Highest probability if the photon – Photo-nuclear interactions for higher energies energy is just above the binding energy (above 10 MeV) of the electron (absorption edge) • Additional energy may be deposited • Without energy deposition locally by Auger electrons and/or – Coherent scattering Photoelectric mass attenuation coefficients fluorescence photons of lead and soft tissue as a function of photon energy. K and L-absorption edges are shown for lead Thomson scattering Photoelectric effect (classical treatment) • Electron tends to be ejected • Elastic scattering of photon (EM wave) on free electron o at 90 for low energy • Electron is accelerated by EM wave and radiates a wave photons, and approaching • No -

Carbon Monoxide in Jupiter After Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9

ICARUS 126, 324±335 (1997) ARTICLE NO. IS965655 Carbon Monoxide in Jupiter after Comet Shoemaker±Levy 9 1 1 KEITH S. NOLL AND DIANE GILMORE Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, Maryland 21218 E-mail: [email protected] 1 ROGER F. KNACKE AND MARIA WOMACK Pennsylvania State University, Erie, Pennsylvania 16563 1 CAITLIN A. GRIFFITH Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011 AND 1 GLENN ORTON Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California 91109 Received February 5, 1996; revised November 5, 1996 for roughly half the mass. In high-temperature shocks, Observations of the carbon monoxide fundamental vibra- most of the O is converted to CO (Zahnle and MacLow tion±rotation band near 4.7 mm before and after the impacts 1995), making CO one of the more abundant products of of the fragments of Comet Shoemaker±Levy 9 showed no de- a large impact. tectable changes in the R5 and R7 lines, with one possible By contrast, oxygen is a rare element in Jupiter's upper exception. Observations of the G-impact site 21 hr after impact atmosphere. The principal reservoir of oxygen in Jupiter's do not show CO emission, indicating that the heated portions atmosphere is water. The Galileo Probe Mass Spectrome- of the stratosphere had cooled by that time. The large abun- ter found a mixing ratio of H OtoH of X(H O) # 3.7 3 dances of CO detected at the millibar pressure level by millime- 2 2 2 24 P et al. ter wave observations did not extend deeper in Jupiter's atmo- 10 at P 11 bars (Niemann 1996). -

"Ringing" from an Asteroid Collision Event Which Triggered the Flood?

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 6 Print Reference: Pages 255-261 Article 23 2008 Is the Moon's Orbit "Ringing" from an Asteroid Collision Event which Triggered the Flood? Ronald G. Samec Bob Jones University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Samec, Ronald G. (2008) "Is the Moon's Orbit "Ringing" from an Asteroid Collision Event which Triggered the Flood?," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 6 , Article 23. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol6/iss1/23 In A. A. Snelling (Ed.) (2008). Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Creationism (pp. 255–261). Pittsburgh, PA: Creation Science Fellowship and Dallas, TX: Institute for Creation Research. Is the Moon’s Orbit “Ringing” from an Asteroid Collision Event which Triggered the Flood? Ronald G. Samec, Ph. D., M. A., B. A., Physics Department, Bob Jones University, Greenville, SC 29614 Abstract We use ordinary Newtonian orbital mechanics to explore the possibility that near side lunar maria are giant impact basins left over from a catastrophic impact event that caused the present orbital configuration of the moon. -

Particles and Deep Inelastic Scattering

Heidi Schellman Northwestern Particles and Deep Inelastic Scattering Heidi Schellman Northwestern University HUGS - JLab - June 2010 June 2010 HUGS 1 Heidi Schellman Northwestern k’ k q P P’ A generic scatter of a lepton off of some target. kµ and k0µ are the 4-momenta of the lepton and P µ and P 0µ indicate the target and the final state of the target, which may consist of many particles. qµ = kµ − k0µ is the 4-momentum transfer to the target. June 2010 HUGS 2 Heidi Schellman Northwestern Lorentz invariants k’ k q P P’ 2 2 02 2 2 2 02 2 2 2 The 5 invariant masses k = m` , k = m`0, P = M , P ≡ W , q ≡ −Q are invariants. In addition you can define 3 Mandelstam variables: s = (k + P )2, t = (k − k0)2 and u = (P − k0)2. 2 2 2 2 s + t + u = m` + M + m`0 + W . There are also handy variables ν = (p · q)=M , x = Q2=2Mµ and y = (p · q)=(p · k). June 2010 HUGS 3 Heidi Schellman Northwestern In the lab frame k’ k θ q M P’ The beam k is going in the z direction. Confine the scatter to the x − z plane. µ k = (Ek; 0; 0; k) P µ = (M; 0; 0; 0) 0µ 0 0 0 k = (Ek; k sin θ; 0; k cos θ) qµ = kµ − k0µ June 2010 HUGS 4 Heidi Schellman Northwestern In the lab frame k’ k θ q M P’ 2 2 2 s = ECM = 2EkM + M − m ! 2EkM 2 0 0 2 02 0 t = −Q = −2EkEk + 2kk cos θ + mk + mk ! −2kk (1 − cos θ) 0 ν = (p · q)=M = Ek − Ek energy transfer to target 0 y = (p · q)=(p · k) = (Ek − Ek)=Ek the inelasticity P 02 = W 2 = 2Mν + M 2 − Q2 invariant mass of P 0µ June 2010 HUGS 5 Heidi Schellman Northwestern In the CM frame k’ k q P P’ The beam k is going in the z direction. -

The Effects of Elastic Scattering in Neutral Atom Transport D

The effects of elastic scattering in neutral atom transport D. N. Ruzic Citation: Phys. Fluids B 5, 3140 (1993); doi: 10.1063/1.860651 View online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.860651 View Table of Contents: http://pop.aip.org/resource/1/PFBPEI/v5/i9 Published by the American Institute of Physics. Related Articles Dissociation mechanisms of excited CH3X (X = Cl, Br, and I) formed via high-energy electron transfer using alkali metal targets J. Chem. Phys. 137, 184308 (2012) Efficient method for quantum calculations of molecule-molecule scattering properties in a magnetic field J. Chem. Phys. 137, 024103 (2012) Scattering resonances in slow NH3–He collisions J. Chem. Phys. 136, 074301 (2012) Accurate time dependent wave packet calculations for the N + OH reaction J. Chem. Phys. 135, 104307 (2011) The k-j-j′ vector correlation in inelastic and reactive scattering J. Chem. Phys. 135, 084305 (2011) Additional information on Phys. Fluids B Journal Homepage: http://pop.aip.org/ Journal Information: http://pop.aip.org/about/about_the_journal Top downloads: http://pop.aip.org/features/most_downloaded Information for Authors: http://pop.aip.org/authors Downloaded 23 Dec 2012 to 192.17.144.173. Redistribution subject to AIP license or copyright; see http://pop.aip.org/about/rights_and_permissions The effects of elastic scattering in neutral atom transport D. N. Ruzic University of Illinois, 103South Goodwin Avenue, Urbana Illinois 61801 (Received 14 December 1992; accepted21 May 1993) Neutral atom elastic collisions are one of the dominant interactions in the edge of a high recycling diverted plasma. Starting from the quantum interatomic potentials, the scattering functions are derived for H on H ‘, H on Hz, and He on Hz in the energy range of 0. -

Relativistic Kinematics of Particle Interactions Introduction

le kin rel.tex Relativistic Kinematics of Particle Interactions byW von Schlipp e, March2002 1. Notation; 4-vectors, covariant and contravariant comp onents, metric tensor, invariants. 2. Lorentz transformation; frequently used reference frames: Lab frame, centre-of-mass frame; Minkowski metric, rapidity. 3. Two-b o dy decays. 4. Three-b o dy decays. 5. Particle collisions. 6. Elastic collisions. 7. Inelastic collisions: quasi-elastic collisions, particle creation. 8. Deep inelastic scattering. 9. Phase space integrals. Intro duction These notes are intended to provide a summary of the essentials of relativistic kinematics of particle reactions. A basic familiarity with the sp ecial theory of relativity is assumed. Most derivations are omitted: it is assumed that the interested reader will b e able to verify the results, which usually requires no more than elementary algebra. Only the phase space calculations are done in some detail since we recognise that they are frequently a bit of a struggle. For a deep er study of this sub ject the reader should consult the monograph on particle kinematics byByckling and Ka jantie. Section 1 sets the scene with an intro duction of the notation used here. Although other notations and conventions are used elsewhere, I present only one version which I b elieveto b e the one most frequently encountered in the literature on particle physics, notably in such widely used textb o oks as Relativistic Quantum Mechanics by Bjorken and Drell and in the b o oks listed in the bibliography. This is followed in section 2 by a brief discussion of the Lorentz transformation. -

Cosmic Collisions” Planetarium Show

“Cosmic Collisions” Planetarium Show Theme: A Tour of the Universe within the context of “Things Colliding with Other Things” The educational value of NASM Theater programming is that the stunning visual images displayed engage the interest and desire to learn in students of all ages. The programs do not substitute for an in-depth learning experience, but they do facilitate learning and provide a framework for additional study elaborations, both as part of the Museum visit and afterward. See the “Alignment with Standards” table for details regarding how Cosmic Collisions and its associated classroom extensions meet specific national standards of learning (SoL’s). Cosmic Collisions takes its audience on a tour of the Universe, from the very small (nuclear fusion processes powering our Sun) to the very large (galaxies), all in the context of the role “collisions” have in the overall scheme of things. Since the concept of large-scale collisions engages the attention of most learners of any age, Cosmic Collisions can be the starting point of a broader learning experience. What you will see in the Cosmic Collisions program: • Meteors (“shooting stars”) – fragments of a comet colliding with Earth’s atmosphere • The Impact Theory of the formation of the Moon • Collisions between hydrogen atoms in solar interior, resulting in nuclear fusion • Charged particles in the Solar Wind creating an aurora display when they hit Earth’s atmosphere • The very large impact that “killed the dinosaurs” • Future impact risk?!? – Perhaps flying a spaceship alongside would deflect enough… • Stellar collisions within a globular cluster • The Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies collide Learning Elaboration While Visiting the National Air and Space Museum Thousands of books and articles have been written about astronomy, but a good starting point is the many books and related materials available at the Museum Store in each NASM building. -

Elastic Scattering, Fusion, and Breakup of Light Exotic Nuclei

Eur. Phys. J. A (2016) 52: 123 THE EUROPEAN DOI 10.1140/epja/i2016-16123-1 PHYSICAL JOURNAL A Review Elastic scattering, fusion, and breakup of light exotic nuclei J.J. Kolata1,a, V. Guimar˜aes2, and E.F. Aguilera3 1 Physics Department, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 46556-5670, USA 2 Instituto de F`ısica,Universidade de S˜aoPaulo, Rua do Mat˜ao,1371, 05508-090, S˜aoPaulo, SP, Brazil 3 Departamento de Aceleradores, Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Nucleares, Apartado Postal 18-1027, C´odigoPostal 11801, M´exico, Distrito Federal, Mexico Received: 18 February 2016 Published online: 10 May 2016 c The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Communicated by N. Alamanos Abstract. The present status of fusion reactions involving light (A<20) radioactive projectiles at energies around the Coulomb barrier (E<10 MeV per nucleon) is reviewed, emphasizing measurements made within the last decade. Data on elastic scattering (providing total reaction cross section information) and breakup channels for the involved systems, demonstrating the relationship between these and the fusion channel, are also reviewed. Similarities and differences in the behavior of fusion and total reaction cross section data concerning halo nuclei, weakly-bound but less exotic projectiles, and strongly-bound systems are discussed. One difference in the behavior of fusion excitation functions near the Coulomb barrier seems to emerge between neutron-halo and proton-halo systems. The role of charge has been investigated by comparing the fusion excitation functions, properly scaled, for different neutron- and proton-rich systems. Possible physical explanations for the observed differences are also reviewed. -

Status of Electron Transport Cross Sections

A11102 mob2fl NBS PUBLICATIONS AlllOb MOflOAb NBSIR 82-2572 Status of Electron Transport Cross Sections U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Bureau of Standards Washington, DC 20234 September 1 982 Prepared for: Office of Naval Research Arlington, Virginia 22217 Space Science Data Center NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 20771 Office of Health and Environmental Research Department of Energy jyj Washington, DC 20545 c.2 '»AT10*AL. BURKAU OF »TAMTARJ»a LIBRARY SEP 2 0 1982 NBSIR 82-2572 STATUS OF ELECTRON TRANSPORT CROSS SECTIONS S. M. Seltzer and M. J. Berger U S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Bureau of Standards Washington, DC 20234 September 1 982 Prepared for: Office of Naval Research Arlington, Virginia 22217 Space Science Data Center NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 20771 Office of Health and Environmental Research Department of Energy Washington, DC 20545 (A Q * U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, Malcolm Baldrige, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS, Ernest Ambler, Director u r ju ' ^ l. .• .. w > - H *+ Status of Electron Transport Cross Sections Stephen M. Seltzer and Martin J. Berger National Bureau of Standards Washington, D.C. 20234 This report describes recent developments and improvements pertaining to cross sections for electron-photon transport calculations. The topics discussed include: (1) electron stopping power (mean excitation energies, density-effect correction); (2) bremsstrahlung production by electrons (radiative stopping power, spectrum of emitted photons); (3) elastic scattering of electrons by atoms; (4) electron-impact ionization of atoms. Key words: bremsstrahlung; cross sections; elastic scattering; electron- impact ionization; electrons; photons; stopping power; transport. Summary of a paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Nuclear Society, June 7-11, 1982, Los Angeles, California.