Just-In-Time Collision Avoidance (JCA) Using a Cloud of Particles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10. Collisions • Use Conservation of Momentum and Energy and The

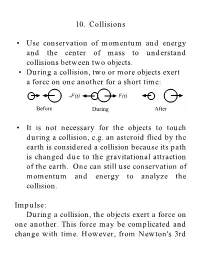

10. Collisions • Use conservation of momentum and energy and the center of mass to understand collisions between two objects. • During a collision, two or more objects exert a force on one another for a short time: -F(t) F(t) Before During After • It is not necessary for the objects to touch during a collision, e.g. an asteroid flied by the earth is considered a collision because its path is changed due to the gravitational attraction of the earth. One can still use conservation of momentum and energy to analyze the collision. Impulse: During a collision, the objects exert a force on one another. This force may be complicated and change with time. However, from Newton's 3rd Law, the two objects must exert an equal and opposite force on one another. F(t) t ti tf Dt From Newton'sr 2nd Law: dp r = F (t) dt r r dp = F (t)dt r r r r tf p f - pi = Dp = ò F (t)dt ti The change in the momentum is defined as the impulse of the collision. • Impulse is a vector quantity. Impulse-Linear Momentum Theorem: In a collision, the impulse on an object is equal to the change in momentum: r r J = Dp Conservation of Linear Momentum: In a system of two or more particles that are colliding, the forces that these objects exert on one another are internal forces. These internal forces cannot change the momentum of the system. Only an external force can change the momentum. The linear momentum of a closed isolated system is conserved during a collision of objects within the system. -

The Physics of a Car Collision by Andrew Zimmerman Jones, Thoughtco.Com on 09.10.19 Word Count 947 Level MAX

The physics of a car collision By Andrew Zimmerman Jones, ThoughtCo.com on 09.10.19 Word Count 947 Level MAX Image 1. A crash test dummy sits inside a Toyota Corolla during the 2017 North American International Auto Show in Detroit, Michigan. Crash test dummies are used to predict the injuries that a human might sustain in a car crash. Photo by: Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images During a car crash, energy is transferred from the vehicle to whatever it hits, be it another vehicle or a stationary object. This transfer of energy, depending on variables that alter states of motion, can cause injuries and damage cars and property. The object that was struck will either absorb the energy thrust upon it or possibly transfer that energy back to the vehicle that struck it. Focusing on the distinction between force and energy can help explain the physics involved. Force: Colliding With A Wall Car crashes are clear examples of how Newton's Laws of Motion work. His first law of motion, also referred to as the law of inertia, asserts that an object in motion will stay in motion unless an external force acts upon it. Conversely, if an object is at rest, it will remain at rest until an unbalanced force acts upon it. Consider a situation in which car A collides with a static, unbreakable wall. The situation begins with car A traveling at a velocity (v) and, upon colliding with the wall, ending with a velocity of 0. The force of this situation is defined by Newton's second law of motion, which uses the equation of This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. -

Carbon Monoxide in Jupiter After Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9

ICARUS 126, 324±335 (1997) ARTICLE NO. IS965655 Carbon Monoxide in Jupiter after Comet Shoemaker±Levy 9 1 1 KEITH S. NOLL AND DIANE GILMORE Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, Maryland 21218 E-mail: [email protected] 1 ROGER F. KNACKE AND MARIA WOMACK Pennsylvania State University, Erie, Pennsylvania 16563 1 CAITLIN A. GRIFFITH Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011 AND 1 GLENN ORTON Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California 91109 Received February 5, 1996; revised November 5, 1996 for roughly half the mass. In high-temperature shocks, Observations of the carbon monoxide fundamental vibra- most of the O is converted to CO (Zahnle and MacLow tion±rotation band near 4.7 mm before and after the impacts 1995), making CO one of the more abundant products of of the fragments of Comet Shoemaker±Levy 9 showed no de- a large impact. tectable changes in the R5 and R7 lines, with one possible By contrast, oxygen is a rare element in Jupiter's upper exception. Observations of the G-impact site 21 hr after impact atmosphere. The principal reservoir of oxygen in Jupiter's do not show CO emission, indicating that the heated portions atmosphere is water. The Galileo Probe Mass Spectrome- of the stratosphere had cooled by that time. The large abun- ter found a mixing ratio of H OtoH of X(H O) # 3.7 3 dances of CO detected at the millibar pressure level by millime- 2 2 2 24 P et al. ter wave observations did not extend deeper in Jupiter's atmo- 10 at P 11 bars (Niemann 1996). -

"Ringing" from an Asteroid Collision Event Which Triggered the Flood?

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 6 Print Reference: Pages 255-261 Article 23 2008 Is the Moon's Orbit "Ringing" from an Asteroid Collision Event which Triggered the Flood? Ronald G. Samec Bob Jones University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Samec, Ronald G. (2008) "Is the Moon's Orbit "Ringing" from an Asteroid Collision Event which Triggered the Flood?," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 6 , Article 23. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol6/iss1/23 In A. A. Snelling (Ed.) (2008). Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Creationism (pp. 255–261). Pittsburgh, PA: Creation Science Fellowship and Dallas, TX: Institute for Creation Research. Is the Moon’s Orbit “Ringing” from an Asteroid Collision Event which Triggered the Flood? Ronald G. Samec, Ph. D., M. A., B. A., Physics Department, Bob Jones University, Greenville, SC 29614 Abstract We use ordinary Newtonian orbital mechanics to explore the possibility that near side lunar maria are giant impact basins left over from a catastrophic impact event that caused the present orbital configuration of the moon. -

Relativistic Kinematics of Particle Interactions Introduction

le kin rel.tex Relativistic Kinematics of Particle Interactions byW von Schlipp e, March2002 1. Notation; 4-vectors, covariant and contravariant comp onents, metric tensor, invariants. 2. Lorentz transformation; frequently used reference frames: Lab frame, centre-of-mass frame; Minkowski metric, rapidity. 3. Two-b o dy decays. 4. Three-b o dy decays. 5. Particle collisions. 6. Elastic collisions. 7. Inelastic collisions: quasi-elastic collisions, particle creation. 8. Deep inelastic scattering. 9. Phase space integrals. Intro duction These notes are intended to provide a summary of the essentials of relativistic kinematics of particle reactions. A basic familiarity with the sp ecial theory of relativity is assumed. Most derivations are omitted: it is assumed that the interested reader will b e able to verify the results, which usually requires no more than elementary algebra. Only the phase space calculations are done in some detail since we recognise that they are frequently a bit of a struggle. For a deep er study of this sub ject the reader should consult the monograph on particle kinematics byByckling and Ka jantie. Section 1 sets the scene with an intro duction of the notation used here. Although other notations and conventions are used elsewhere, I present only one version which I b elieveto b e the one most frequently encountered in the literature on particle physics, notably in such widely used textb o oks as Relativistic Quantum Mechanics by Bjorken and Drell and in the b o oks listed in the bibliography. This is followed in section 2 by a brief discussion of the Lorentz transformation. -

Cosmic Collisions” Planetarium Show

“Cosmic Collisions” Planetarium Show Theme: A Tour of the Universe within the context of “Things Colliding with Other Things” The educational value of NASM Theater programming is that the stunning visual images displayed engage the interest and desire to learn in students of all ages. The programs do not substitute for an in-depth learning experience, but they do facilitate learning and provide a framework for additional study elaborations, both as part of the Museum visit and afterward. See the “Alignment with Standards” table for details regarding how Cosmic Collisions and its associated classroom extensions meet specific national standards of learning (SoL’s). Cosmic Collisions takes its audience on a tour of the Universe, from the very small (nuclear fusion processes powering our Sun) to the very large (galaxies), all in the context of the role “collisions” have in the overall scheme of things. Since the concept of large-scale collisions engages the attention of most learners of any age, Cosmic Collisions can be the starting point of a broader learning experience. What you will see in the Cosmic Collisions program: • Meteors (“shooting stars”) – fragments of a comet colliding with Earth’s atmosphere • The Impact Theory of the formation of the Moon • Collisions between hydrogen atoms in solar interior, resulting in nuclear fusion • Charged particles in the Solar Wind creating an aurora display when they hit Earth’s atmosphere • The very large impact that “killed the dinosaurs” • Future impact risk?!? – Perhaps flying a spaceship alongside would deflect enough… • Stellar collisions within a globular cluster • The Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies collide Learning Elaboration While Visiting the National Air and Space Museum Thousands of books and articles have been written about astronomy, but a good starting point is the many books and related materials available at the Museum Store in each NASM building. -

Collision-Free Kinematics for Redundant Manipulators in Dynamic Scenes Using Optimal Reciprocal Velocity Obstacles*

Collision-Free Kinematics for Redundant Manipulators in Dynamic Scenes using Optimal Reciprocal Velocity Obstacles* Liangliang Zhao1, Jingdong Zhao1, Hong Liu1, and Dinesh Manocha2 Abstract— We present a novel algorithm for collision-free kinematics of multiple manipulators in a shared workspace with moving obstacles. Our optimization-based approach simultaneously handles collision-free constraints based on reciprocal velocity obstacles and inverse kinematics constraints for high-DOF manipulators. We present an efficient method based on particle swarm optimization that can generate collision-free configurations for each redundant manipulator. Furthermore, our approach can be used to compute safe and oscillation-free trajectories in a few milli-seconds. We highlight the real-time performance of our algorithm on multiple Baxter robots with 14-DOF manipulators operating in a workspace with dynamic obstacles. Videos are available at https://sites.google.com/view/collision-free-kinematics I. INTRODUCTION Redundant manipulators are widely used in complex and cluttered environments for various kinds of tasks. Moreover, Fig 1. Solving inverse kinematics on a Baxter robots many applications use multiple manipulators that work manipulator (7-DOF) in the workspace. Our algorithm can cooperatively in an environment with moving obstacles (e.g. compute the inverse kinematics solutions for these humans). To perform the tasks, the planning algorithms must redundant manipulators, and avoid collisions (red sphere) compute trajectories that simultaneously satisfy two sets of between the robots. The blue line is the desired path of the constraints: end effector. 1. Inverse Kinematics Constraints: Given the pose of workspace among other redundant manipulators and static or each end-effector, we need to compute joint dynamic obstacles. -

Part Fourteen Kinematics of Elastic Neutron Scattering

22.05 Reactor Physics - Part Fourteen Kinematics of Elastic Neutron Scattering 1. Multi-Group Theory: The next method that we will study for reactor analysis and design is multi-group theory. This approach entails dividing the range of possible neutron energies into small regions, ΔEi and then defining a group cross-section that is averaged over each energy group i. Neutrons enter each group as the result of either fission (recall the distribution function for fission neutrons) or scattering. Accordingly, we need a thorough understanding of the scattering process before proceeding. 2. Types of Scattering: Fission neutrons are born at high energies (>1 MeV). However, the fission reaction is best sustained by neutrons that are at thermal energies with “thermal” defined as 0.025 eV. It is only at these low energies that the cross-section of U-235 is appreciable. So, a major challenge in reactor design is to moderate or slow down the fission neutrons. This can be achieved via either elastic or inelastic scattering: a) Elastic Scatter: Kinetic energy is conserved. This mechanism works well for neutrons with energies 10 MeV or below. Light nuclei, ones with low mass number, are best because the lighter the nucleus, the larger the fraction of energy lost per collision. b) Inelastic Scatter: The neutron forms an excited state with the target nucleus. This requires energy and the process is only effective for neutron energies above 0.1 MeV. Collisions with iron nuclei are the preferred approach. Neutron scattering is important in two aspects of nuclear engineering. One is the aforementioned neutron moderation. -

Exploration of the Universe with Reaction Machines

EXPLORINGTHE UNKNOWN 59 Document 1-5 Document title: A.A. Blagonravov, Editor in Chief, Collected Works of KE. Tiokovskiy, Vol- ume ZZ - Reactive Plying Machines, Translation of “K.E. Tsiolkovskiy, Sobraniye Sochmeniy, Tom II - Reaktivnyye Letatal’nyye Apparaty,” Izdatel’stvo Akademii Nauk SSSR, Moscow, 1954, NASA lT F-237,1965, pp. 72-117. Konstantin Tsiolkovskiy was a school teacher who lived in the small town of Kaluga, Russia. He is regarded by the Russians as the founder of Soviet rocketry, much as Robert Goddard and Hermann Oberth are regarded as the fathers of American and German rocketry in their respective countries. He is responsible for associating the term Sputnik, or “fellow traveller,” to artificial satellites. But Tsiolkovskiy’swork was almost entirely theo- retical and was not widely known or translated outside of Russia, until after his death. This article, written in 1898 and first published in 1903, established the fundamen- tals of orbital mechanics and proposed the then-radical use of both liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen as fuel. It appeared seventeen years before Goddard repeated much of’ the work in the United States and twenty-three years before he began the first experiments with liquid propellants. It was also the first detailed discussion of a manned space station. The fact that it was not translated until much later meant that its impact on rocket re- search around the world was minimal. Exploration of the Universe with Reaction Machines Heights Reached by Balloons; Their Size and Weight; the Temperature and Density of the Atmosphere 1. So far small unmanned aerostats carrying automatic observation equipment have risen to altitudes of not more than 22 km. -

Lecture 16 Collisions

LECTURE 16 COLLISIONS Lecture Instructor: Kazumi Tolich Lecture 16 2 ¨ Reading chapter 9-5 to 9-6 ¤ Collisions n Completely inelastic collisions n Elastic collisions Collisions 3 ¨ The total linear momentum of the colliding objects is always conserved during any collision. ¨ In an elastic collision, the total kinetic energy of the system remains the same. ¨ In an inelastic collision, the total kinetic energy changes. ¤ In an extreme case of a completely inelastic collision, all objects share a common velocity at the end of the collision. Quiz: 1 4 ¨ A compact car and a large truck collide head-on and stick together. Which undergoes the larger momentum change? A. Car B. Truck C. The momentum change is the same for both vehicles. D. Cannot tell without knowing the final velocity of combined mass. Quiz: 16-1 answer 5 ¨ The momentum change is the same for both vehicles. ¨ Conservation of momentum tells us that the changes in momentum must add up to zero: ∆�#$#%& = ∆�#()*+ + ∆�*%(= � ¨ So the change in the car’s momentum must be equal to the change in the truck’s momentum, and the two changes must be in the opposite directions. Quiz: 2 ¨ Two cars of equal mass travel in opposite directions at equal speeds. They collide in a completely inelastic collision. Just after the collision, their velocities are A. zero. B. equal to their original velocities. C. equal in magnitude but opposite in direction from their original velocities. D. less in magnitude and in the same direction as their original velocities. Quiz: 16-2 answer ¨ zero. ¨ Since two cars of equal mass travel in opposite directions at equal speeds before the collision, the total momentum of the two-car system is zero. -

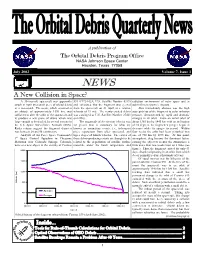

A New Collision in Space? a 30-Year-Old Spacecraft Was Apparently 539 (1972-102A, U.S

A publication of The Orbital Debris Program Office NASA Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas 77058 July 2002 Volume 7, Issue 3. NEWS A New Collision in Space? A 30-year-old spacecraft was apparently 539 (1972-102A, U.S. Satellite Number 6319) radiation environment of outer space and to struck in April by a small piece of orbital debris and calculated that the fragment was ejected sub-millimeter particle impacts. or a meteoroid. The event, which occurred at from the spacecraft on 21 April at a relative Also immediately obvious was the high an altitude of approximately 1370 km, was velocity of 19 m/s. The newly created debris susceptibility of the fragment to solar radiation sufficient to alter the orbit of the spacecraft and was cataloged as U.S. Satellite Number 27423 pressure, demonstrated by rapid and dramatic to produce a new piece of debris which was on 6 May. changes in its orbit. From an initial orbit of large enough to be tracked by several sensors in The magnitude of the ejection velocity was about 1365 km by 1445 km with an inclination the U.S. Space Surveillance Network (SSN). far greater than is customary for what are of 74 degrees, the fragment’s perigee began to Radar returns suggest the fragment diameter known as anomalous events, i.e., infrequent decrease while its apogee increased. Within was between 20 and 50 centimeters. piece separations from older spacecraft and four weeks the orbit had been perturbed into Analysts of Air Force Space Command’s upper stages of launch vehicles. -

MOON FORMATION at the END of a COLLISION CHAIN Erik Asphaug

51st Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2020) 1292.pdf MOON FORMATION AT THE END OF A COLLISION CHAIN Erik Asphaug and Alexandre Emsenhuber Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA ([email protected]) Introduction. a) Initial collision b) Further c) Subsequent collision In the standard model of Moon forma- Earth and Theia do not merge dynamical Earth and Theia merge tion, a Mars-sized planet collides with proto-Earth at a but mix evolution and a disk is formed ◦ nominal impact angle θcoll ∼ 45 and at vcoll close to vesc, i.e. v1 ≈ 0. It is a graze and merge collision (GMC), the most common kind of pairwise planetary merger [1]. Powerful torques are generated when the cores and in- ner mantles merge. Silicates, derived mainly from the Figure 1: Summary of our model. (a) Two original plan- smaller planet by proportion of angular momentum about ets mix somewhat in an HRC and the runner loses a frac- the new center of mass, go into orbit [2]. The Moon, thus − tion of its mantle. (b) Interlude for ∼ 103 6 years where composed mostly of Theia, would be isotopically dis- Theia is the runner. (c) Return collision is much slower, tinct, but it is not. Another puzzle is how such a slow col- consistent with the standard model. The two impacts are lision would come about, requiring a Mars-sized planet randomly aligned so the disk has high inclination. existing quite close to Earth [3] – a configuration that is not readily explained, and that has to go unstable in the end.