A Multiple Impact Origin for the Moon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-References ASTEROID IMPACT Definition and Introduction History of Impact Cratering Studies

18 ASTEROID IMPACT Tedesco, E. F., Noah, P. V., Noah, M., and Price, S. D., 2002. The identification and confirmation of impact structures on supplemental IRAS minor planet survey. The Astronomical Earth were developed: (a) crater morphology, (b) geo- 123 – Journal, , 1056 1085. physical anomalies, (c) evidence for shock metamor- Tholen, D. J., and Barucci, M. A., 1989. Asteroid taxonomy. In Binzel, R. P., Gehrels, T., and Matthews, M. S. (eds.), phism, and (d) the presence of meteorites or geochemical Asteroids II. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 298–315. evidence for traces of the meteoritic projectile – of which Yeomans, D., and Baalke, R., 2009. Near Earth Object Program. only (c) and (d) can provide confirming evidence. Remote Available from World Wide Web: http://neo.jpl.nasa.gov/ sensing, including morphological observations, as well programs. as geophysical studies, cannot provide confirming evi- dence – which requires the study of actual rock samples. Cross-references Impacts influenced the geological and biological evolu- tion of our own planet; the best known example is the link Albedo between the 200-km-diameter Chicxulub impact structure Asteroid Impact Asteroid Impact Mitigation in Mexico and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary. Under- Asteroid Impact Prediction standing impact structures, their formation processes, Torino Scale and their consequences should be of interest not only to Earth and planetary scientists, but also to society in general. ASTEROID IMPACT History of impact cratering studies In the geological sciences, it has only recently been recog- Christian Koeberl nized how important the process of impact cratering is on Natural History Museum, Vienna, Austria a planetary scale. -

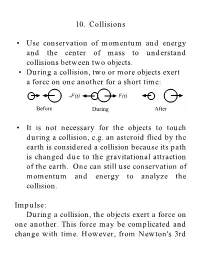

10. Collisions • Use Conservation of Momentum and Energy and The

10. Collisions • Use conservation of momentum and energy and the center of mass to understand collisions between two objects. • During a collision, two or more objects exert a force on one another for a short time: -F(t) F(t) Before During After • It is not necessary for the objects to touch during a collision, e.g. an asteroid flied by the earth is considered a collision because its path is changed due to the gravitational attraction of the earth. One can still use conservation of momentum and energy to analyze the collision. Impulse: During a collision, the objects exert a force on one another. This force may be complicated and change with time. However, from Newton's 3rd Law, the two objects must exert an equal and opposite force on one another. F(t) t ti tf Dt From Newton'sr 2nd Law: dp r = F (t) dt r r dp = F (t)dt r r r r tf p f - pi = Dp = ò F (t)dt ti The change in the momentum is defined as the impulse of the collision. • Impulse is a vector quantity. Impulse-Linear Momentum Theorem: In a collision, the impulse on an object is equal to the change in momentum: r r J = Dp Conservation of Linear Momentum: In a system of two or more particles that are colliding, the forces that these objects exert on one another are internal forces. These internal forces cannot change the momentum of the system. Only an external force can change the momentum. The linear momentum of a closed isolated system is conserved during a collision of objects within the system. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

The Physics of a Car Collision by Andrew Zimmerman Jones, Thoughtco.Com on 09.10.19 Word Count 947 Level MAX

The physics of a car collision By Andrew Zimmerman Jones, ThoughtCo.com on 09.10.19 Word Count 947 Level MAX Image 1. A crash test dummy sits inside a Toyota Corolla during the 2017 North American International Auto Show in Detroit, Michigan. Crash test dummies are used to predict the injuries that a human might sustain in a car crash. Photo by: Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images During a car crash, energy is transferred from the vehicle to whatever it hits, be it another vehicle or a stationary object. This transfer of energy, depending on variables that alter states of motion, can cause injuries and damage cars and property. The object that was struck will either absorb the energy thrust upon it or possibly transfer that energy back to the vehicle that struck it. Focusing on the distinction between force and energy can help explain the physics involved. Force: Colliding With A Wall Car crashes are clear examples of how Newton's Laws of Motion work. His first law of motion, also referred to as the law of inertia, asserts that an object in motion will stay in motion unless an external force acts upon it. Conversely, if an object is at rest, it will remain at rest until an unbalanced force acts upon it. Consider a situation in which car A collides with a static, unbreakable wall. The situation begins with car A traveling at a velocity (v) and, upon colliding with the wall, ending with a velocity of 0. The force of this situation is defined by Newton's second law of motion, which uses the equation of This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. -

Mercurian Impact Ejecta: Meteorites and Mantle

Meteoritics & Planetary Science 44, Nr 2, 285–291 (2009) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org Mercurian impact ejecta: Meteorites and mantle Brett GLADMAN* and Jaime COFFEY University of British Columbia, Department of Physics and Astronomy, 6244 Agricultural Road, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z1, Canada *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] (Submitted 28 January 2008; revision accepted 15 October2008) Abstract–We have examined the fate of impact ejecta liberated from the surface of Mercury due to impacts by comets or asteroids, in order to study 1) meteorite transfer to Earth, and 2) reaccumulation of an expelled mantle in giant-impact scenarios seeking to explain Mercury’s large core. In the context of meteorite transfer during the last 30 Myr, we note that Mercury’s impact ejecta leave the planet’s surface much faster (on average) than other planets in the solar system because it is the only planet where impact speeds routinely range from 5 to 20 times the planet’s escape speed; this causes impact ejecta to leave its surface moving many times faster than needed to escape its gravitational pull. Thus, a large fraction of Mercurian ejecta may reach heliocentric orbit with speeds sufficiently high for Earth-crossing orbits to exist immediately after impact, resulting in larger fractions of the ejecta reaching Earth as meteorites. We calculate the delivery rate to Earth on a time scale of 30 Myr (typical of stony meteorites from the asteroid belt) and show that several percent of the high-speed ejecta reach Earth (a factor of 2–3 less than typical launches from Mars); this is one to two orders of magnitude more efficient than previous estimates. -

Carbon Monoxide in Jupiter After Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9

ICARUS 126, 324±335 (1997) ARTICLE NO. IS965655 Carbon Monoxide in Jupiter after Comet Shoemaker±Levy 9 1 1 KEITH S. NOLL AND DIANE GILMORE Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, Maryland 21218 E-mail: [email protected] 1 ROGER F. KNACKE AND MARIA WOMACK Pennsylvania State University, Erie, Pennsylvania 16563 1 CAITLIN A. GRIFFITH Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011 AND 1 GLENN ORTON Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California 91109 Received February 5, 1996; revised November 5, 1996 for roughly half the mass. In high-temperature shocks, Observations of the carbon monoxide fundamental vibra- most of the O is converted to CO (Zahnle and MacLow tion±rotation band near 4.7 mm before and after the impacts 1995), making CO one of the more abundant products of of the fragments of Comet Shoemaker±Levy 9 showed no de- a large impact. tectable changes in the R5 and R7 lines, with one possible By contrast, oxygen is a rare element in Jupiter's upper exception. Observations of the G-impact site 21 hr after impact atmosphere. The principal reservoir of oxygen in Jupiter's do not show CO emission, indicating that the heated portions atmosphere is water. The Galileo Probe Mass Spectrome- of the stratosphere had cooled by that time. The large abun- ter found a mixing ratio of H OtoH of X(H O) # 3.7 3 dances of CO detected at the millibar pressure level by millime- 2 2 2 24 P et al. ter wave observations did not extend deeper in Jupiter's atmo- 10 at P 11 bars (Niemann 1996). -

TESTS of the GIANT IMPACT HYPOTHESIS. J. H. Jones, Mail Code SN2, NASA Johnson Space Cen- Ter, Houston TX 77058, USA ([email protected])

Origin of the Earth and Moon Conference 4045.pdf TESTS OF THE GIANT IMPACT HYPOTHESIS. J. H. Jones, Mail Code SN2, NASA Johnson Space Cen- ter, Houston TX 77058, USA ([email protected]). Introduction: The Giant Impact hypothesis [1] mantle. The best argument against this is the observa- has gained popularity as a means of producing a vola- tion of Meisel et al. [9] that the Os isotopic composi- tile-depleted Moon, that still has a chemical affinity to tion of fertile spinel lherzolites approaches chondritic. the Earth [e.g., 2]. As Taylor’s Axiom decrees, the Because Os is compatible and Re incompatible during best models of lunar origin are testable, but this is basalt genesis, this close approach to chondritic Os difficult with the Giant Impact model [1]. The energy would not ordinarily be expected if spinel lherzolites associated with the impact is sufficient to totally melt formed by the mixing of random, differentiated litholo- and partially vaporize the Earth [3]. And this means gies. Thus, it seems likely that there are mantle sam- that there should be no geological vestige of earlier ples that have never been processed by a magma ocean. times. Accordingly, it is important to devise tests that may be used to evaluate the Giant Impact hypothesis. Are Tungsten Isotopes in the Earth and Moon Three such tests are discussed here. None of these is the Same? No. Lee and coworkers [10, 11] have pre- supportive of the Giant Impact model, but neither do sented W isotopic data for both the Earth and Moon. -

Decadal Origin

Lunar Pyroclastic Deposits and the Origin of the Moon1 Harrison H. Schmitt2 Introduction: The Consensus Debate over the origin and evolution of the Moon, and implications relative to the Earth, has remained lively and productive since the last human exploration of that small planet in 1972. More recently, issues related to the evolution of Mars, Venus and Mercury have received increasing attention from the planetary geology community and the public as many robotic missions have augmented the earlier lunar investigations. A number of generally accepted hypotheses relative to the history of the Moon and the terrestrial planets (e.g., Sputis 1996, Canup and Righter 2000, Taylor 2001, Warren 2003, Palme 2004), however, deserve intense questioning as data from many of the lunar samples suggest alternatives to some of these hypotheses. Further, how much do the known, probable and possible events in lunar history constrain what may have occurred on and in Mars? Or, indeed, do such events constrain what may have happened on and in the Earth? Strong agreement exists that at 4.567 ± 0.001 Gyr (T0) (Carlson and Lugmair 2000, Alexander et al 2001, Taylor 2001, Jacobsen 2003, Amelin et al 2004) a portion of an interstellar molecular cloud collapsed to form the solar nebula (Taylor 2001, Hester et al 2004). A sizable consensus also exists that a few tens of millions of years after T0, the Moon belatedly came into existence as a result of a "giant impact" between the very young Earth and a chondritic asteroid that was 11 to 14 percent the mass of the Earth and gave a combined angular momentum of 110-120 percent of the current Earth-Moon system (Hartmann and Davis 1975, Cameron and Ward 1976, Hartmann 1986, Cameron 2002, Canup 2004, Palme 2004). -

Moon-Earth-Sun: the Oldest Three-Body Problem

Moon-Earth-Sun: The oldest three-body problem Martin C. Gutzwiller IBM Research Center, Yorktown Heights, New York 10598 The daily motion of the Moon through the sky has many unusual features that a careful observer can discover without the help of instruments. The three different frequencies for the three degrees of freedom have been known very accurately for 3000 years, and the geometric explanation of the Greek astronomers was basically correct. Whereas Kepler’s laws are sufficient for describing the motion of the planets around the Sun, even the most obvious facts about the lunar motion cannot be understood without the gravitational attraction of both the Earth and the Sun. Newton discussed this problem at great length, and with mixed success; it was the only testing ground for his Universal Gravitation. This background for today’s many-body theory is discussed in some detail because all the guiding principles for our understanding can be traced to the earliest developments of astronomy. They are the oldest results of scientific inquiry, and they were the first ones to be confirmed by the great physicist-mathematicians of the 18th century. By a variety of methods, Laplace was able to claim complete agreement of celestial mechanics with the astronomical observations. Lagrange initiated a new trend wherein the mathematical problems of mechanics could all be solved by the same uniform process; canonical transformations eventually won the field. They were used for the first time on a large scale by Delaunay to find the ultimate solution of the lunar problem by perturbing the solution of the two-body Earth-Moon problem. -

"Ringing" from an Asteroid Collision Event Which Triggered the Flood?

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 6 Print Reference: Pages 255-261 Article 23 2008 Is the Moon's Orbit "Ringing" from an Asteroid Collision Event which Triggered the Flood? Ronald G. Samec Bob Jones University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Samec, Ronald G. (2008) "Is the Moon's Orbit "Ringing" from an Asteroid Collision Event which Triggered the Flood?," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 6 , Article 23. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol6/iss1/23 In A. A. Snelling (Ed.) (2008). Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Creationism (pp. 255–261). Pittsburgh, PA: Creation Science Fellowship and Dallas, TX: Institute for Creation Research. Is the Moon’s Orbit “Ringing” from an Asteroid Collision Event which Triggered the Flood? Ronald G. Samec, Ph. D., M. A., B. A., Physics Department, Bob Jones University, Greenville, SC 29614 Abstract We use ordinary Newtonian orbital mechanics to explore the possibility that near side lunar maria are giant impact basins left over from a catastrophic impact event that caused the present orbital configuration of the moon. -

Dean Cain Bettina Zimmermann

DEAN CAIN BETTINA ZIMMERMANN POST IMPACT POST IMPACT In 2012, a meteor crashes into tion plane to Europe is destroyed Siberia with the force of several by a mysterious satellite signal, thousand nuclear warheads. In controlled from the ruins of Berlin, 2015, a few survivors will travel a city that was considered dead into “the death zone”, to try and and buried – under 30 feet of ice locate a device that could give and snow – the President of the mankind new hope – or forever New United Northern Sates orders finish it… a new expedition to find and destroy the base and the satellite. In 2012, a meteor strikes Earth, Tom Parker (Dean Cain) volunteers causing earthquakes, tidal waves, to lead a group of highly trained and a dust cloud that soon covers specialists on a suicide mission most of the Northern hemisphere, to Berlin – with ground vehicles, turning it into an ice-covered no reliable intel, and zero radio “death-zone”. contact. Three years later, most of the sur- In the ruins of what was once one vivors have settled in the only hab- of the most dynamic cities in itable territories below the equa- Europe, a desperate fight ensues tor. It’s a harsh life, with little hope for the power to change every- of Earth’s climate ever reverting thing – for better or for worse… back to normal. When an expedi- POST IMPACT SNOWBLIND LLC presents a TANDEM PRODUCTIONS GMBH, UFO IPS LLC in co-production with LUCKY 7 PRODUCTIONS LLC and AMERICAN FILM CINEMA in association with RTL TELEVISION GMBH and THE TOWER LIMITED LIABILITY PARTNERSHIP Production -

Post-Impact Hydrothermal Activity in Meteorite Impact Craters and Potential Opportunities for Life

Bioastronomy 2002: Life Among the Stars IAU Symposium, Vol. 213, 2004 R.P.Norris and F.H.Stootman (eds.) Post-Impact Hydrothermal Activity in Meteorite Impact Craters and Potential Opportunities for Life Christian Koeberl Department of Geological Sciences, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria, [email protected] Wolf Uwe Reimold Impact Cratering Research Group, School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2050, South Africa, [email protected] Abstract. Impact craters are prominent landforms on all objects with a solid surface in the solar system. The formation of an impact structure is a high-energy, high-temperature transient event which introduces large amounts of energy into a limited area. This energy can, in part, be expanded on the creation and activation of a hydrothermal system within and even outside of the crater. Depending on the crater size and geology of the target region, this hydrothermal system may persist for extended periods of time. Such impact-induced hydrothermal systems could well have provided conditions supportive of the development of life on the early Earth and it is not unreasonable to assume that similar conditions could have led to life-favoring circumstances on other planets and satellites. 1. Introduction Studies during the last few decades have convinced most workers that the planets formed by collision and hierarchical growth starting from small objects, Le., from dust to planetesimals to planets. All planets and satellites of the solar system that have solid surfaces (e.g., Mercury, Venus, Mars, the asteroids) are covered by craters. Impact cratering has been either the most important, or one of the most important processes that affected the shaping of their surfaces.