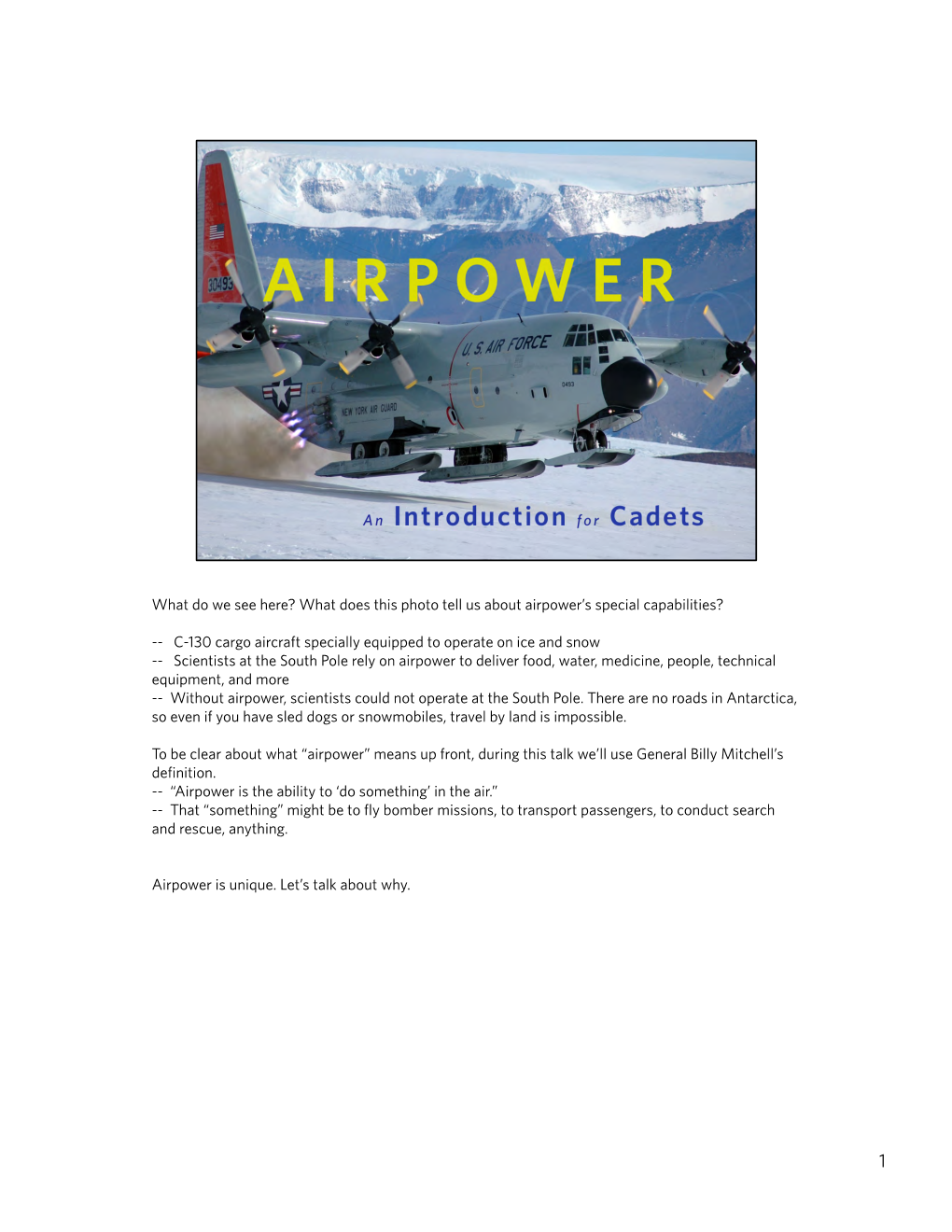

What Does This Photo Tell Us About Airpower's Special Capabilities?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B-25 Mitchell

Airpower Classics Artwork by Zaur Eylanbekov B-25 Mitchell On April 18, 1942, Army Air Forces Lt. Col. James “Pappy” Gunn’s fabled 75 mm cannon. The Mitchell H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, leading a force of 16 B-25B was never the fastest, most maneuverable, or medium bombers and crews, took off from the best-looking medium bomber. However, it grew to aircraft carrier USS Hornet and bombed Tokyo be the most heavily armed and was more versatile and other targets. It was the first time US aircraft than any—even the German Junkers Ju 88. had struck at Japan, and the raid immortalized both Doolittle and the B-25 Mitchell. The North Noted for its excellent handling characteristics, the American Aviation bomber went on to become a B-25 performed remarkably well in many roles, workhorse in every theater of World War II. including medium- and low-altitude bomber, close air support, photo reconnaissance, anti- North American proposed the new Model NA-62, submarine warfare, patrol, and—when occasion derived from a series of earlier prototypes, in a demanded—tactical fighter. Later it was used as 1939 competition. The Army bought it right off a pilot and navigator trainer, and became much the drawing board, ordering 184 of the airplanes. beloved in that role. In peacetime, it served as an The clean, lean lines of the B-25 delivered good executive transport, firefighter, camera airplane, performance and facilitated both mass produc- test vehicle, and crop duster. The last B-25 train- tion and maintenance. Built in 10 major models, ers remained in service at Reese AFB, Tex., until with numerous variants, the B-25 was particularly finally retiring in January 1959—nearly 17 years adaptable to field modifications. -

Cincinnati's Doolittle Raider at War

Queen City Heritage Thomas C. Griffin, a resident of Cincinnati for over forty years, participated in the first bombing raid on Japan in World War II, the now leg- endary Doolittle raid. (CHS Photograph Collection) Winter 1992 Navigating from Shangri-La Navigating from Shangri- La: Cincinnati's Doolittle Raider at War Kevin C. McHugh served as Cincinnati's oral historian for "one of America's biggest gambles"5 of World War II, the now legendary Doolittle Raid on Japan. A soft-spoken man, Mr. Griffin Over a half century ago on April 18, 1942, characteristically downplays his part in the first bombing the Cincinnati Enquirer reported: "Washington, April 18 raid on Japan: "[It] just caught the fancy of the American — (AP) — The War and Navy Departments had no confir- people. A lot of people had a lot worse assignments."6 mation immediately on the Japanese announcement of the Nevertheless, he has shared his wartime experiences with bombing of Tokyo."1 Questions had been raised when Cincinnati and the country, both in speaking engagements Tokyo radio, monitored by UPI in San Francisco, had sud- and in print. In 1962 to celebrate the twentieth anniversary denly gone off the air and then had interrupted program- of the historic mission, the Cincinnati Enquirer highlight- ming for a news "flash": ed Mr. Griffin's recollections in an article that began, Enemy bombers appeared over Tokyo for the "Bomber Strike from Carrier Recalled."7 For the fiftieth first time since the outbreak of the current war of Greater anniversary in 1992, the Cincinnati Post shared his adven- East Asia. -

Beneficial Bombing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters University of Nebraska Press Fall 2010 Beneficial Bombing Mark Clodfelter Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Clodfelter, Mark, "Beneficial Bombing" (2010). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 37. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/37 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. runninghead 1 2 3 4 ( ##& 5 6 7 8 )'#(! 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 i Buy the Book Benecial Bombing—Clodfelter Roger Buchholz, designer Studies in War, Society, and the Military general editors Peter Maslowski University of Nebraska–Lincoln David Graff Kansas State University Reina Pennington Norwich University editorial board D’Ann Campbell Director of Government and Foundation Relations, U.S. Coast Guard Foundation Mark A. Clodfelter National War College Brooks D. Simpson Arizona State University Roger J. Spiller George C. Marshall Professor of Military History U.S. Army Command and General Staff College (retired) Timothy H. E. Travers University of Calgary Arthur Waldron Lauder Professor of International Relations University of Pennsylvania Buy the Book FM3-Title page Recto Use page pdf as supplied. -

Jimmy Doolittle E Commander Behind the Legend

THE 17 DREW PER PA S Jimmy Doolittle e Commander behind the Legend Benjamin W. Bishop Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Air University Steven L. Kwast, Lieutenant General, Commander and President School of Advanced Air and Space Studies Thomas D. McCarthy, Colonel, Commandant and Dean AIR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ADVANCED AIR AND SPACE STUDIES Jimmy Doolittle The Commander behind the Legend Benjamin W. Bishop Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Drew Paper No. 17 Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Project Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jerry Gantt Bishop, Benjamin W., 1975– Copy Editor Jimmy Doolittle, the commander behind the legend / Tammi K. Dacus Benjamin W. Bishop, Lieutenant Colonel, USAF. pages cm. — (Drew paper, ISSN 1941-3785 ; no. 17) Cover Art, Book Design, and Illustrations Includes bibliographical references. Daniel Armstrong ISBN 978-1-58566-245-6 Composition and Prepress Production 1. Doolittle, James Harold, 1896-1993—Military leadership. Michele D. Harrell 2. Generals—United States—Biography. 3. Command of Print Preparation and Distribution troops—Case studies. 4. United States. Army Air Forces. Air Diane Clark Force, 8th. 5. World War, 1939-1945—Aerial operations, Amer- ican. I. Title. UG626.2.D66B57 2014 940.54’4973092—dc23 2014035210 AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS Published by Air University Press in February 2015 ISBN: 978-1-58566-245-6 Director and Publisher ISSN: 1941-3785 Allen G. Peck Editor in Chief Oreste M. Johnson Managing Editor Demorah Hayes -

By John T. Correll

The Billy Mitchell Court-Martial By John T. Correll 62 AIR FORCE Magazine / August 2012 In the Army’s view, the issue was The Billy Mitchell insubordination, not the val idity of Court-Martial Mitchell’s claims. y 1925, Billy Mitchell had grade of colonel. It was an important alienated almost everybody job in a significant command, but in the War Department and Mitchell felt he had been demoted and Navy Department, to say sent to the boondocks. The airmen in nothing of President Calvin Texas still called him “General.” BCoolidge. Strident in his advocacy of Two Navy aircraft mishaps soon airpower, Mitchell did not hesitate to caused Mitchell’s temper to boil over lash out when he disagreed with his in even more spectacular fashion than superiors, which was often. “The Gen- usual. The worst of the accidents was eral Staff knows as much about the air the breakup of the Navy dirigible as a hog does about skating,” he said. Shenandoah over Ava, Ohio, Sept. William Mitchell (no middle name) 3. The airship was on a publicity came to fame as the combat leader junket, due to pass over 27 cities at of American air forces in France in times announced in advance to please World War I. He was promoted to the politicians and their constituents. Over temporary grade of brigadier general Ohio, Shenandoah ran into a line squall and kept his star after the war because of intense thunderstorms but did not of his assignment as assistant chief of divert around it, remaining on course the Army Air Service. -

The Birth of American Airpower in World War I Commemorating the 100Th Anniversary of the US Entry Into the “Great War” Dr

The Birth of American Airpower in World War I Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the US Entry into the “Great War” Dr. Bert Frandsen* Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Air and Space Power Journal requests a courtesy line. lthough the Wright Brothers invented the airplane, the birth of American air- power did not take place until the United States entered the First World War. When Congress declared war on 6 April 1917, the American air arm was Anothing more than a small branch of the Signal Corps, and it was far behind the air forces of the warring European nations. The “Great War,” then in its third year, had *Portions of this article have been previously published by the author who has written extensively on American airpower in World War I. The article, in whole, has not been previously published. 60 | Air & Space Power Journal The Birth of American Airpower in World War I nothing more than a small branch of the Signal Corps, and it was far behind the air forces of the warring European nations. The “Great War,” then in its third year, had witnessed the development of large air services with specialized aircraft for the missions of observation, bombardment, and pursuit. -

Brigadier General Billy Mitchell's Stamp

CHAPTER 3 Artist’s rendering of P-51B Mustangs in aerial combat Tomas Picka/Shutterstock The Evolution of the Early Air Force Chapter Outline LESSON 1 The Army Air Corps LESSON 2 Airpower in World War II LESSON 3 Signifi cant Aircraft of World War II Allied Air power was decisive in the war in Western Europe…. ‘‘In the air, its victory was complete. At sea, its contribution, combined with naval power, brought an end to the enemy’s greatest naval threat—the U-boat; on land, it helped turn the tide overwhelmingly in favor of Allied ground forces. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey, 1945’’ LESSON 1 The Army Air Corps FTER WORLD WAR I Brigadier General William Quick Write “Billy” Mitchell wanted to fi nd a way to get A military leaders and the US Congress to pay attention to his calls for an independent air service. He’d seen how airpower helped turn the war in the The Army, Navy, and Allies’ favor. This included the major role of aircraft Congress were reluctant to create an equal branch in the Battle of Saint Mihiel in 1918. of the military dedicated Airpower was emerging as an offensive weapon to airpower. After reading the story about Brigadier and a powerful defensive tool. Mitchell thought General Billy Mitchell, the Army Air Service ought to be under its own explain how he drew command. But the Army, Navy, and Congress saw attention to airpower’s potential. things differently. To them, airpower was auxiliary— functioning as a branch of another military organization—to the Army’s ground forces. -

Creating the Air Force, 1924 Introduction Questions for Discussion

1 Creating the Air Force, 1924 Introduction In this July 1924 letter to aviation pioneer and publisher Lester D. Gardner, Brigadier General William “Billy” Mitchell prophesied the coming tide of Japanese militarism. Concerned about Japan’s growing military power in the skies, Mitchell argued exhaustively for the creation a branch of the US military separate from the Army and Navy and dedicated to the air. “With the development of our methods,” he wrote, “we can absolutely dominate sea areas practically anywhere. It is the only sure method of national defense that we have at the present time where we could dominate.” Following World War I, the US military scaled back its focus on the development of a formidable air force. Without a dedicated US air force, and facing the prowess and strength of Japanese aviation, Mitchell foresaw destruction as the outcome of any future American military intervention in Japan. Of the US Navy, Mitchell wrote: “if they went anywhere near Japan they never would come back: the Japanese air force would destroy them at once.” Mitchell’s outspoken criticism of his superiors earned him a demotion to colonel the year after this letter was written, and he was forced into an early retirement following a court martial conviction stemming from his accusations against military leadership. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, brought to life the threat Mitchell had warned of two decades earlier. Mitchell, however, did not live to see his predictions come true. He died on February 19, 1936. Following the Pearl Harbor attack, however, Mitchell was posthumously promoted to major general, and in 1946 he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in recognition of his tremendous foresight concerning the development of America’s aviation forces. -

Captain Eddie Rickenbacker Lead

Volume 15 Number 007 The Last Full Measure – Captain Eddie Rickenbacker Lead: For 400 years service men and women have fought to carve out and defend freedom and the civilization we know as America. This series on A Moment in Time is devoted to the memory of those warriors, whose devotion gave, in the words of Lincoln at Gettysburg, the last full measure. Intro.: A Moment in Time with Dan Roberts. Content: His racing exploits earned him the name "Fast Eddie." He participated in the 1912, 1914 1915 and 1916 Indianapolis 500 and ended up years later buying the racetrack and running it until 1945. Yet, it was in the air that Edward Vernon Rickenbacker revealed true genius, courage, and skill. Born the third child of eight to William and Elizabeth Rickenbacker of Columbus, Ohio in 1890, he revealed a daring spirit from almost the beginning. His years as a racecar driver gave him a lucrative income and also brought him into contact with pilots of those newfangled air machines. An intensely patriotic man, Rickenbacker changed the spelling of his name during World War I removing the Germanic "h," and substituting a second old-fashioned Anglicized "k." Soon after the war began, he volunteered for service. At first he was assigned as a driver to Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, but then he was asked to apply his mechanics skills to the car of Col. Billy Mitchell, Chief of the U.S. Army Air Service. Soon he was training for air combat and soon after being assigned to the famed 94th Aero Squadron, on April 6, 1918, he brought down his first enemy airplane. -

William “Billy” Mitchell's Air Power

William “Billy” Mitchell’s Air Power Compiled from the published and unpublished writings and commentaries of William Mitchell by LT COL JOHNNY R. JONES, USAF Airpower Research Institute College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-5532 September 1997 DISCLAIMER Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. ii Contents Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii PREFACE . ix INTRODUCTION . xi The Essence of Air Power . 1 Fundamental Truths of Air Power . 5 The Aeronautical Era . 15 Air Power and the Air Force . 19 Air Power and Control of the Air . 25 Airmen in Air Power . 29 Air Power and Armies and Navies . 35 Air Power and Armies . 36 Air Power and Navies . 38 Training and Education for Air Power . 41 Air Power Functions . 43 Conclusion . 45 Notes . 47 iii Foreword In the fall of 1996, the Department of the Air Force published its vision for the twenty-first century Air Force. The vision, entitled Global Engagement, presented a new strategy to guide the Air Force in meeting the many challenges of the first quarter of the twenty-first century. It is a vision “of air and space power and covers all aspects of our Air Force—people, capabilities, and support structures.” 1 Global Engagement “is the first step in the Air Force’s back-to-the-present approach to long-range planning.”2 As the Air Force charts its course into the twenty-first century, valuable insight is gained by examining the beginnings of that course—the initial vector that has steered air power from its birth at the beginning of this century and will now carry air and space power into the next. -

30, Leadership in the Old Air Force: a Postgraduate Assignment., David

'The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Air Force, Department of Defense or the US Government.'" USAFA Harmon Memorial Lecture #30 Leadership in the Old Air Force: A Postgraduate Assignment David MacIsaac , 1987 We Americans have a peculiar propensity to single out for special notice those anniversaries measured in multiple decennia-as in a tenth reunion, a thirtieth anniversary, a fortieth birthday, a centennial, and so forth. Accordingly, the 17th of September this year will be marked by celebrations attendant to the bicentennial of the adoption by the Constitutional Convention of the Constitution of the United States. In similar if less august manner, the 18th of September will mark the fortieth anniversary of the establishment of the United States Air Force as a separate service. It was eighty years ago August 1, 1907, that the Army Signal Corps established an Aeronautical Division to take charge "of all matters pertaining to military ballooning, air machines, and all kindred subjects." Allotted to carry out this task were one captain, one corporal, and one private. When the latter went OTF (over the fence) shortly thereafter, the 1907 version of regression analysis revealed, as some late twentieth-century stylist might put it, "grave difficulties in maintaining necessary manning levels."1 But help was on the way. Only two months earlier a young Pennsylvanian, a founding member and acknowledged leader of the "Black Hand" (a secret, nocturnal society of Bed Check Charlies and assorted other pranksters at West Point), ranking academically near the top of the bottom half of his class, and having spent the final four days before commencement on the tour ramp, was graduated from the Military Academy, having failed ever to be appointed a cadet officer. -

The Air Campaign: John Warden and the Classical Airpower Theorists By

The Air Campaign John Warden and the Classical Airpower Theorists DAVID R. METS Revised Edition Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 1999 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mets, David R. The air campaign : John Warden and the classical airpower theorists / David R. Mets. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Air power. 2. Air warfare. 3. Military planning. 4. Warden, John A., 1943– . I. Title UG630.M37797 1998 358.4—dc21 98-33838 CIP Revised April 1999 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii PREFACE . ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . xi 1 THE CONTEXT: A DIFFERENT MIND-SET . 1 The Mind-Set in World War I . 1 Post-World War I Posture . 4 Notes . 8 2 GIULIO DOUHET . 11 A Continental Theorist . 11 Organization for War . 14 Impact . 15 Notes . 18 3 HUGH TRENCHARD . 21 British Empire Theorist . 21 Organization for War . 23 Notes . 29 4 WILLIAM MITCHELL . 31 New World Theorist . 31 Organization for War . 37 Notes . 50 5 JOHN WARDEN . 55 Theorist or Throwback? . 55 Organization for War . 62 Notes . 69 iii Chapter Page 6 CONCLUSIONS . 73 Notes . 79 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 81 INDEX . 85 Photographs Gen Billy Mitchell and Gen Mason M. Patrick . 32 Gen James Doolittle . 35 USS Saratoga . 41 Gen Oscar Westover . 45 Gen Frank Andrews .