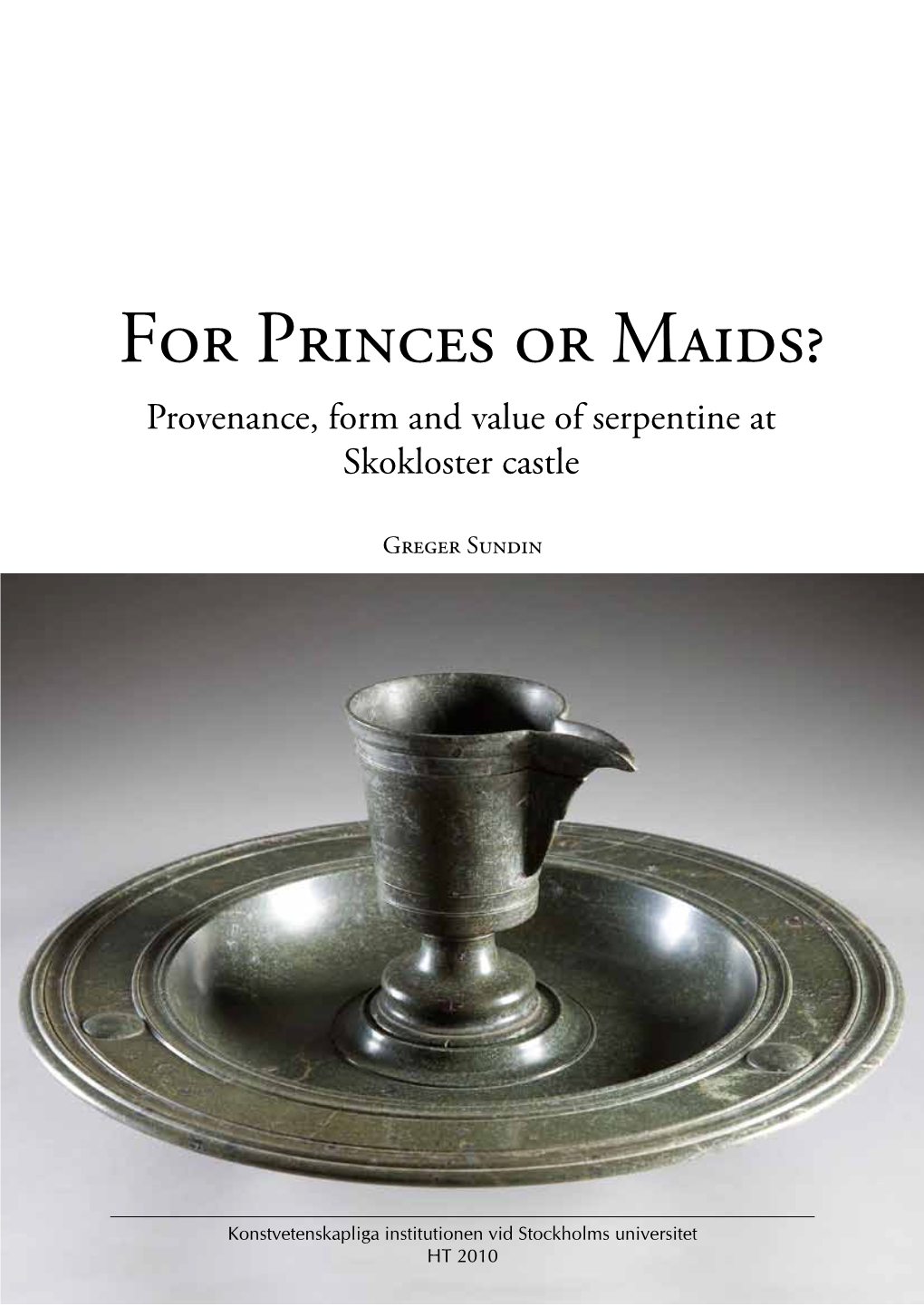

For Princes Or Maids?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strömsholm Skokloster

Strömsholm Skokloster On an islet in the Kolbäck River, Gustav Vasa Skokloster Castle, one of Europe´s best pre- built a fortress in the early 1550s, which was served baroque castles, lies in a scenic setting on largely dismantled in the late 1660s. At this the shores of Lake Mälaren, close to Arlanda time, Strömsholm was part of a cluster of Airport, and between Stockholm and Uppsala. properties at the disposal of Dowager Queen Skokloster Castle dates from the 17th century, Hedvig Eleonora. It was her idea to tear Sweden’s period as a great power in Europe. down the old fortress and build something The Castle is the largest private residence ever entirely new. Just as with Drottningholm, built in the country. The building was commis- the Dowager Queen consulted the architect sioned by Field Marshal, Count Carl Gustaf Nicodemus Tessin the Elder. Wrangel. The State Apartment is open for Strömsholm consists of a large edifice free flow, but you can also join a more extensive framed by four square towers. Facing the tour with a guide. Stroll through beautiful park, a central tower rises to a large dome. rooms with furniture, paintings and textiles. During the reign of Hedvig Eleonora, Guided tours end up in one of the largest some twenty buildings were erected on the and best preserved 17th century armouries in grounds. A large park, inspired by the French the world. In the Museum Shop you will find baroque, was also landscaped. books, postcards and souvenirs. Enjoy a break Open daily throughout the summer, when in the Castle Café under 17th century vaults, you can enjoy dining in the stone kitchen. -

Archaeology of Denmark and Sweden 23 – 30 September 2019 from £2295.00

Archaeology of Denmark and Sweden 23 – 30 September 2019 from £2295.00 The neighbouring Nordic nations of Sweden and Denmark offer a host of archaeological and historical sites, from Neolithic megaliths to Viking forts, from fairytale castles to a magnificent royal warship. We begin in Uppsala in Sweden, with visits to the archaeological sites at Gamla Uppsala and Anundshög and the baroque Skokloster Castle. In Stockholm we tour the excellent Historical Museum and visit the Vasa Museum, which houses the heavily armed and richly decorated royal warship which sank on its maiden voyage in 1628. A relaxing high-speed rail journey follows as we travel from Stockholm to Malmö in the south of Sweden. Here we tour the Osterlen region, with visits to the megalithic monuments known as Ales Stenar before crossing the Öresund Bridge to Copenhagen. We have a day touring the Danish capital, including the renaissance castle of Rosenborg Slot, then transfer to Aarhus in mainland Denmark. From here we visit the Moesgård Viking Museum and the Viking Castle at Fyrkat, learning much about the real story behind those notorious Norsemen. We also come face to face with some former inhabitants of the region as we visit Silkeborg Museum, home to the ‘bog bodies’, the amazingly well-preserved remains of a man and woman who died here around 350BC. Itinerary Monday 23 September 2019 We depart this morning on a direct flight from Manchester to Stockholm Arlanda in Sweden (provisional times with SAS: 0945/1345). On arrival we transfer by coach to Uppsala and a visit to the archaeological site at Gamla Uppsala. -

Gustavplaybook.Pdf

GustavUnder theAdolf Lily the Banners Great 11 Dirschau 1627 • Honigfelde 1629 • Breitenfeld 1631 • Alte Veste 1632 • Lützen 1632 PLAY BOOK Table of Contents All Scenarios .................................................................. 2 Dramatis Personae.................................................. 36 Polish Wars Special Rules.............................................. 4 Swedish Kings and Queens .................................... 37 Dirschau / Tczew ............................................................ 5 The Swedish-Polish Wars of the 17th Centure ...... 38 Honingfelde / Trzciano................................................... 9 Polish Army of the 1620s ....................................... 38 Breitenfeld ...................................................................... 12 The Swedish Army of Gustav Adolf ...................... 38 Alte Veste ....................................................................... 20 Game Tactics III ............................................................. 41 Lützen .......................................................................... 26 Bibliography ................................................................... 44 Edgehill Variant .............................................................. 33 Counterscans .................................................................. 45 Historical Notes .............................................................. 36 Charts and Tables ........................................................... 48 GMT Games, LLC 0602 -

Giuseppe Arcimboldo's Composite Portraits and The

Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s Composite Portraits and the Alchemical Universe of the Early Modern Habsburg Court (1546-1612) By Rosalie Anne Nardelli A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Art History in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada July, 2014 Copyright © Rosalie Anne Nardelli, 2014 Abstract At the Renaissance noble court, particularly in the principalities of the Holy Roman Empire, alchemical pursuits were wildly popular and encouraged. By the reign of Rudolf II in the late sixteenth century, Prague had become synonymous with the study of alchemy, as the emperor, renowned for his interest in natural magic, welcomed numerous influential alchemists from across Europe to his imperial residence and private laboratory. Given the prevalence of alchemical activities and the ubiquity of the occult at the Habsburg court, it seems plausible that the art growing out of this context would have been shaped by this unique intellectual climate. In 1562, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, a previously little-known designer of windows and frescoes from Milan, was summoned across the Alps by Ferdinand I to fulfil the role of court portraitist in Vienna. Over the span of a quarter-century, Arcimboldo continued to serve faithfully the Habsburg family, working in various capacities for Maximilian II and later for his successor, Rudolf II, in Prague. As Arcimboldo developed artistically at the Habsburg court, he gained tremendous recognition for his composite portraits, artworks for which he is most well- known today. Through a focused investigation of his Four Seasons, Four Elements, and Vertumnus, a portrait of Rudolf II under the guise of the god of seasons and transformation, an attempt will be made to reveal the alchemical undercurrents present in Arcimboldo’s work. -

1635: the DREESON INCIDENT-ARC Eric Flint &

1635-The Dreeson Incident-ARC Table of Contents PROLOGUE PART ONE Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 PART TWO Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 PART THREE Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 PART FOUR Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Chapter 26 Chapter 27 Chapter 28 Chapter 29 PART FIVE Chapter 30 Chapter 31 Chapter 32 Chapter 33 PART SIX Page 1 Chapter 34 Chapter 35 Chapter 36 Chapter 37 Chapter 38 Chapter 39 Chapter 40 Chapter 41 PART SEVEN Chapter 42 Chapter 43 PART EIGHT Chapter 44 Chapter 45 Chapter 46 Chapter 47 Chapter 48 Chapter 49 Chapter 50 Chapter 51 Chapter 52 Chapter 53 Chapter 54 Chapter 55 PART NINE Chapter 56 Chapter 57 Chapter 58 Chapter 59 Chapter 60 PART TEN Chapter 61 Chapter 62 Chapter 63 Chapter 64 Chapter 65 Chapter 66 PART ELEVEN Chapter 67 Chapter 68 Chapter 69 EPILOGUE 1635: THE DREESON INCIDENT-ARC Eric Flint & Page 2 Virginia DeMarce Advance Reader Copy Unproofed This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental. Copyright © 2008 by Eric Flint & Virginia DeMarce All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form. A Baen Books Original Baen Publishing Enterprises P.O. Box 1403 Riverdale, NY 10471 www.baen.com ISBN 10: 1-4165-5589-7 ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-5589-6 Cover art by Tom Kidd Maps by t/k First printing, December 2008 Distributed by Simon & Schuster 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data t/k 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Pages by Joy Freeman (www.pagesbyjoy.com) Printed in the United States of America The Ring of Fire series: 1632by Eric Flint 1633by Eric Flint & David Weber 1634: The Baltic Warby Eric Flint & David Weber Page 3 Ring of Fireed. -

Förteckning Över

Förteckning över: 1) De la Gardieska släktarkivet från Löberöd; 2) Varia; 3) De övriga släktarkiven i De la Gardieska arkivet (dvs Barnekow, Bille, Boije, Douglas, Ekeblad, Forbus, Gyllenkrook, Horn - von Gertten, Hägerstierna, Kruus, Kämpe, Königsmarck, Lillie, Månsson, Nils, i Skumparp, Oxenstierna, Ramel, Reenstierna, von Reiser, Sparre, Stenbock, Sture, Wrangel, Wrede) upprättad 2008 av Annika Böregård Vapenförbättringsbrev för Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie, 1650 Universitetsbiblioteket, Lunds universitet 1 De la Gardieska samlingen Släktarkiven De la Gardie De la Gardie är en grevlig släkt, härstammande från en fransk borgarsläkt som på oklara grunder tillskrivits adlig status. En del av släkten var dock möjligen lokal lantadel; om det råder delade meningar i forskningen. I Frankrike hette släkten d´Escouperie och den förste kände stamfadern var Robert d´Escouperie (levde omkr. 1387), som uppges ha ägt gårdarna Château Russol och La Gardie i departementet Aude. Släktens svenska gren härstammar från köpmannen Jacques Scoperier (†1565) i staden Caunes nära Carcassonne i södra Frankrike. Hans son Ponce d´Escouperie invandrade till Sverige 1565 och antog namnet Pontus De la Gardie efter en av släktens gårdar i Languedoc. I sitt äktenskap med en illegitim dotter till Johan III blev han far till riksmarsken Jakob de la Gardie som "upphöjdes i grefligt stånd" 10 maj 1615 och introducerades 1625 på Sveriges Riddarhus med nr 3 bland grevar. Denna gren finns fortfarande. I Sverige fanns en gren som 1571 fick friherrelig värdighet men som utslocknade 1640. Samtliga ättemedlemmar, bortsett från stamfadern Pontus, härstammar via hans fru Sofia Johansdotter från hennes far, Johan III. Nuvarande (2007) huvudman för ätten De la Gardie är greve Carl Gustaf De la Gardie, f.1946 och bosatt i Linköping. -

Configuring Virtue: the Emergence of Abstraction, Allegoresis and Emblem in Swedish Figural Sculpture of the Seventeenth Century

Simon McKeown CONFIGURING VIRTUE: THE EMERGENCE OF ABSTRACTION, ALLEGORESIS AND EMBLEM IN SWEDISH FIGURAL SCULPTURE OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY In 1642, the Amsterdam engraver, Crispijn de Passe the Younger pub- lished an unusual emblem book called Den Onderganck des Roomschen Arents door den Noordschen Leeuw (“The Overthrow of the Roman Eagle by the Northern Lion”).1 This work was a hagiographical memorial of the brief, but glorious, intervention of the Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus in the Thirty Years’ War published ten years after his death, and some seven years after that of the book’s author, the preacher Bartholomaeus Hulsius.2 In one of the book’s twenty-nine plates, De Passe presents us with a prospect of Gustavus Adolphus’ mausoleum in Stockholm (Fig. 1). It is depicted as an effigial monument with the figure of the king recum- bent on top of a chest-tomb. He rests under a broad canopy supported by six female statues which act as a species of caryatid. Four of the statues are fully visible to the viewer, and by their attributes are easily readable as personifications of the Cardinal Virtues. From left to right, we find Iustitia (Justice) with sword and scales, Fortitudo (Fortitude) with a col- umn, Temperantia (Temperance) diluting a flagon of wine with water, and DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/BJAH.2015.9.05 1 Bartholomaeus Hulsius, Den Onderganck des Roomschen Arents door den Noordschen Leeuw (Amsterdam: Crispijn de Passe the Younger, 1642). 2 Concerning this work, see Simon McKeown, “A Reformed and Godly Leader: Bartholomaeus Hulsius’s Typological Emblems in Praise of Gustavus Adolphus”, Reformation 5 (2000), 55-101. -

Picturing the Wake: Arcimboldo, Joyce and His ‘Monster,’

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research City College of New York 2012 Picturing the Wake: Arcimboldo, Joyce and his ‘Monster,’ Václav Paris CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_pubs/814 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] JJQ Picturing the Wake: Arcimboldo, Joyce, and His “Monster” Vaclav Paris University of Pennsylvania hrouded in its own obscurity, Finnegans Wake is a book we often think of as visually indistinct. We associate its world Swith Joyce’s near-blindness, with nighttime, and feel our way through, stumbling over words, listening for, rather than seeing, the path. For new readers in particular, the challenge of picturing Joyce’s scenes or characters is formidable. The problem is not that the visual is absent—any given page of Finnegans Wake burgeons with visual details—but rather that we do not or cannot focus on it. We lack a visual framework: a way of reconciling the many details into stable images. How can we see the Wake? What would a visual equivalent look like, and how might we employ it in introducing students to Joyce’s world? This essay attempts to address these questions, pro- posing the paintings of the Renaissance artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo as a model.1 This may seem counterintuuitive. Arcimboldo’s paint- ings, specific as they are, cannot be said to capture the whole world of the Wake, and they do not, in any real sense, illustrate Joyce’s words. -

Compilation A...L Version.Pdf

Compilation and Translation Johannes Widekindi and the Origins of his Work on a Swedish-Russian War Vetushko-Kalevich, Arsenii 2019 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Vetushko-Kalevich, A. (2019). Compilation and Translation: Johannes Widekindi and the Origins of his Work on a Swedish-Russian War. Lund University. Total number of authors: 1 Creative Commons License: Unspecified General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Compilation and Translation Johannes Widekindi and the Origins of his Work on a Swedish-Russian War ARSENII VETUSHKO-KALEVICH FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND THEOLOGY | LUND UNIVERSITY The work of Johannes Widekindi that appeared in 1671 in Swedish as Thet Swenska i Ryssland Tijo åhrs Krijgz-Historie and in 1672 in Latin as Historia Belli Sveco-Moscovitici Decennalis is an important source on Swedish military campaigns in Russia at the beginning of the 17th century. -

Holy Roman Empire

WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 1 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 CONTENT Historical Background Bohemian-Palatine War (1618–1623) Danish intervention (1625–1629) Swedish intervention (1630–1635) French intervention (1635 –1648) Peace of Westphalia SPECIAL RULES DEPLOYMENT Belligerents Commanders ARMY LISTS Baden Bohemia Brandenburg-Prussia Brunswick-Lüneburg Catholic League Croatia Denmark-Norway (1625-9) Denmark-Norway (1643-45) Electorate of the Palatinate (Kurpfalz) England France Hessen-Kassel Holy Roman Empire Hungarian Anti-Habsburg Rebels Hungary & Transylvania Ottoman Empire Polish-Lithuanian (1618-31) Later Polish (1632 -48) Protestant Mercenary (1618-26) Saxony Scotland Spain Sweden (1618 -29) Sweden (1630 -48) United Provinces Zaporozhian Cossacks BATTLES ORDERS OF BATTLE MISCELLANEOUS Community Manufacturers Thanks Books Many thanks to Siegfried Bajohr and the Kurpfalz Feldherren for the pictures of painted figures. You can see them and much more here: http://www.kurpfalz-feldherren.de/ Also thanks to the members of the Grimsby Wargames club for the pictures of painted figures. Homepage with a nice gallery this : http://grimsbywargamessociety.webs.com/ 2 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 3 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 The rulers of the nations neighboring the Holy Roman Empire HISTORICAL BACKGROUND also contributed to the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War: Spain was interested in the German states because it held the territories of the Spanish Netherlands on the western border of the Empire and states within Italy which were connected by land through the Spanish Road. The Dutch revolted against the Spanish domination during the 1560s, leading to a protracted war of independence that led to a truce only in 1609. -

The Cambridge Companion to August Strindberg Edited by Michael Robinson Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-60852-7 - The Cambridge Companion to August Strindberg Edited by Michael Robinson Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to august strindberg August Strindberg is one of the most enduring of nineteenth-century dramatists, and is also an internationally recognized novelist, autobiographer and painter. This Companion presents contributions by leading international scholars on different aspects of Strindberg’s highly colourful life and work. The essays focus primarily on his most celebrated plays; these include the naturalist dramas, The Father and Miss Julie; the experimental dramas with which he created a true modernist theatre – To Damascus and A Dream Play; and the Chamber Plays of 1908 which, like so much of his work, exerted a powerful influence on later twentieth-century drama. His plays are contextualized for what they contribute both to the history of drama and developments in theatre practice, and other essays clarify the enormous importance to these dramas of his other work, most notably the autobiographical novel Inferno, and his lifelong interest in science, the occult, sexual politics and the visual arts. michael robinson is Professor Emeritus of Drama and Scandinavian Studies at the University of East Anglia, Norwich. He is the author of Strindberg and Autobiography (1986) and Studies in Strindberg (1998), and has translated a two-volume selection of Strindberg’s letters (1992), a collection of his essays (1996) and five of the plays (1998). He has edited five volumes of essays on Strindberg and Ibsen, and is also the General Editor of the Cambridge Plays in Production series. His three-volume International Annotated Bibliography of Strindberg Studies was published by the MHRA in 2008. -

Fulltekst (Pdf)

Konstvetenskapliga institutionen ISCENSATTA RYTTARINNOR OCH PERFORMATIVA HÄSTAR EN RYTTARPORTRÄTTSVIT FRÅN TIDIG MODERN TID I SKOKLOSTERS SLOTTS SAMLING Författare: Annika Williams © Masteruppsats i konstvetenskap Vårterminen 2021 Handledare: Henrik Widmark ABSTRACT Institution/Ämne Uppsala universitet. Konstvetenskapliga institutionen, Konstvetenskap Författare Annika Williams Titel och undertitel: Iscensatta ryttarinnor och performativa hästar En ryttarporträttsvit från tidigmodern tid i Skoklosters slotts samling Engelsk titel: Enacted Equestriennes and Performative Horses A Suite of Equestrian Portraits from Early Modern Time in the Skokloster Castle Collection ! Handledare Henrik Widmark! Ventileringstermin: Höstterm. (år) Vårterm. (år) Sommartermin (år) 2021 Innehåll: This essay is a study of a suite of six small-scale equestrian portraits in the Skokloster Castle Collection. The suite represents aristocratic women at the court of Louis XIV. In the portraits, the equestriennes and their horses performe advanced dressage movements. In the 17th Century the advanced dressage riding, performed in l’art du manège, was a masculine sphere. The equestrian portraits in the Skokloster suite therefore evoke questions regarding early modern female horse- and riding culture. How do we read these equestrian portraits today? In the analysis I focus on what the horses and riders do. I discuss La Querelle des femmes and how earlymodern French elite women would search for a new female role. Horseriding would open up for a possibility for women to