History of Meteorology 5 (2009) 126

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Chapter (PDF)

LIST OF COLLABORATORS: EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, BENJAMIN E. SMITH, A.M., L.H.D. EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTORS, CLEVELAND ABBE, A.M., LL.D. JOHN MASON CLARKE, Ph.D., LL.D. Professor of Meteorology, United States New York State Geologist and Paleon- WILLIAM HALLOCK, Ph.D. Weather Bureau. tologist; Director of the State Museum Professor of Physics in Columbia and of the Scicncc Division of the De- University. M ctcorology. partment of Education of the State of New York. Color Photography. LIBERTY HYDE BAILEY, M.S., LL.D. Paleontology; Stratigraphy. Director of the New York State College GEORGE BRUCE HALSTED, Ph.D. of Agriculture, Cornell University. Professor of Mathematics in the Horticulture. FREDERICK VERNON COVILLE, A.B. Colorado State Normal School. Curator of the United States National Mathematics. ITcrbariu m. ADOLPH FRANCIS BANDELIER, Systematic and Economic Botany. Lecturer on American Archaeology in FRANK E. HOBBS, Columbia University. LIEUTENANT-COLONEL, ORDNANCE DEPARTMENT, South American Ethnology and STEWART CULIN. UNITED STATES ARMY. Archeology. Commanding Officer of the Rock Island Numismatics. Arsenal. Ordnajice; Military Arms; Explo- EDWIN ATLEE BARBER, A.M., Ph.D. sives. Director of the Museum of the Pennsylvania EDWARD SALISBURY DANA, Museum and School of Industrial Art. A.M., Ph.D. Ceramics; Glass-making. Professor of Physics and Curator of LELAND OSSIAN HOWARD, Mineralogy in Yale University. M.S., Ph.D. Mineralogy. Chief Entomologist of the United States CHARLES BARNARD. Department of Agriculture; Honorary Curator of the United States National Museum; Consulting Entomologist of Tools and Appliances. the United States Public Health and WILLIAM MORRIS DAVIS, Marine Hospital Service. M.E., Sc.D., Ph.D. -

5. Cleveland Abbe and the Birth of the National Weather Service, 1870

Proceedings of the International Commission on History of Meteorology 1.1 (2004) 5. Cleveland Abbe and the Birth of the National Weather Service, 1870-1891 Edmund P. Willis Kinsale Research Alexandria, Virginia, USA and William H. Hooke American Meteorological Society Washington, DC, USA Cleveland Abbe (1838-1916) made substantial scientific and administrative contributions to nascent national weather services during their first twenty years under the aegis of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Prior studies of the Signal Service, however, give short shrift to Abbe’s work. In particular most accounts barely mention Abbe’s scientific endeavors during the initial decade, 1871-1880.1 This paper examines three aspects of Abbe’s career: (a) his background; (b) the science he initiated; and (c) his administrative accomplishments. Two conclusions emerge: first, Abbe initiated significant, broad-based scientific research, beginning in the 1870s; and second, Abbe’s scientific contributions deserve recognition for their part in the evolution of 19th century meteorology. Abbe shared the background and many of the characteristics of American scientists in the 19th century. His father, George W. Abbe, was a New York merchant of New England ancestry. His parents raised him in the Baptist tradition of service and respect for others. He took his undergraduate degree in 1857 from the Free Academy, forerunner of the City College of New York, where he demonstrated an interest in meteorology. He went on to study astronomy in 1859 at the University of Michigan, and began work with the U. S. Coast Survey in 1860 at its office in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There he acquired a desire for graduate study abroad. -

Catalogue #19

Back of Beyond Books proudly releases Catalogue #19. We continue to feature books and ephemera from the American West but you’ll also find numerous pages of Americana, Travel and Photographic material along with Explora- tion, Mining and Native Americana. We’ve also picked up small collections of Poetry and Art Books which have been fun to catalogue. Perhaps my favorite genre of Catalogue #19 are the 21 Promotional items from western states and communities. These colorful pamphlets, mostly from the early 20th century, would make any Chamber of Commerce proud. It’s always interesting to see what items sell quickly in each catalogue. I of- ten guess wrong so I’ll leave the decisions up to you. Several items of note, however, include: The best association copy known of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian--inscribed to Edward Abbey, a beautifully bright advertising poster for the ‘Field Self Discharging Rake’, a scarce promotional for the Salt River Valley of Arizona, a full-plate tintype from Volcano, California, and six large format albumen photographs depicting archaeological sites of Arizona and New Mexico by John K. Hillers. I’m also taken with the striking and rare Broadside for the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, the very clean re- view copy of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and the atlas from the Pike Expe- dition published in 1810. Thanks to my staff at the store for working around the piles and boxes of books. If you’re ever in Moab our shop is open daily; please stop in. Sophie Tomkiewicz used the skills she learned at the Colorado Rare Books School in developing Catalogue #19 and Eric Trenbeath is our designer. -

Eossibilitvof Your Going Far Wrong If

In th<* picturesque b^roujrh of Bristol on the "res* nt> drlc^St*- from Wm>hin?toa to AX jfSPKDITION AKTKR T11K SIN. * Africa*. < )f tbf mulrr* WIVES OF WELL-KNOWN MEN. batiks or territory j binam-n, the Delaware ;u the fertile the Conferees. but. his be¬ a. wi.h 'U< . 011. I ". and i^-riraltur.il FROM THE NEW STATES. Fifty-fir,it territory Eumpua tongu al:. xwjit A. Sri.town*. ^ suburban county ot Bucks in Pennsylvania coming a state. bo Kive»u;> that position to rep¬ The I»cnsacola's Trl>> to the African believe. o( tlie Uurt>Kf< of Turkey and Fin¬ TMi. \\!X: AkU IJQron MIIICHAHT. la a a wocwU'ii with resent. in imrt. the new state spaciou> old-timo mansion of Washington in Cornt land. are spoken among the sailors. If Sunday Uu take* loairMloi of kia many interesting aud sometimessad experience*! the United States Senate. morning in a pleasant one. an-l instead of at¬ Some Ladies Who Are Prominent in of this was MAGNIFICENT NEW STORES AND family history. For many years Some I SEMATOB SQVIRK. scientists who jtovkbed to sea sickness. tending church, where few sailors are to be the home of F. Gi'lke-on. in the of the Senators Who we roam about tnc deck of the WISE VAII.TR. Benjamin Represent His colleague. Watson C. is a native life ON BOARD A MAN-OF-WAR DESCRIBED BT found, upper Washington Society. restoration of rule the influence of Squire, shiD, we shall see men at cards, bask¬ 1500and 170V Banna. -

Tradition Versus History in American Meteorology

FEBRUARY,1930 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW 65 TRADITION VERSUS HISTORY IN AMERICAN METEOROLOGY ERICR. MILLER The claims of the biographers of Matthew Font,aine The incident referred to in the foregoing quotat)ions, Maury that he was the founder of our national weather the initiation of meteorological telegrams for the benefit of service have been discounted by Charles F. Brooks (l), commerce and navigation as a function of the Signal but in trying to avoid Scylla, Brooks runs into Charybdis Service of the Army, is easily accessible in the official when lie says that Cleveland Abbe’s forec,asting service at records. Cincinnati grew into the national weather servke.’ A memorial written by Increase A. Lapham, of Mil- Inasmuch as the intere.st in the history of science and wauke,e, Wis., on December 8, 1869, and addressed to in the lives of scientists is now inc.reasing, it may be of Gen. Halbert E. Paine, Member of Congress from the interest to writers of test,books and of enayclopedias, t’o congressional district in which Milwaukae is located, learn of other c,lrtirns that have no more basis than those induced Paine to prepare a bill (H. R. 603) whic.h he just ment,ioned. The following have been estracted from int,roduced on December 16, 1869. Paine obtained let- sources that would naturally be regarded as of the highest t,ers in support of his bill from the following persons: authority: J. K. Barnes, Surgeon General, United States Army. James Pollard Espy “organized a sen7ic.e of daily Joseph Henry, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. -

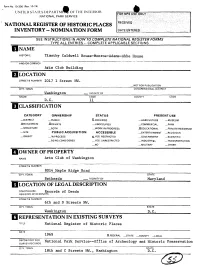

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNiTEDSTATES DEPARTMlW Oh THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Timothy Caldwell House-Monroe-Adams-Abbe House AND/OR COMMON Arts Club Building LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER 2017 I Street NW, —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Washington _ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE D.C. 11 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) _XPRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -XEDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED — INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Arts Club of Washington STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Maryland LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, Records of Deeds REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. STREET & NUMBER 6th and D Streets NW. CITY, TOWN STATE Washington D.C. 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE National Register of Historic Places DATE 1969 XFEDERAL _STATE _COUNTY __LOCAL DEPOSITORYFOR National Park Service—Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE 18th and C Streets NW., Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^.EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED ^.UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The following architectural description is taken from the National Register Nomination Form for 2017 I Street. The form was prepared in 1969 and there have been no significant changes to the property since then. -

ˁabbās Wasīm Efendi

A A ˁAbbās Wasīm Efendi which was originally written in Persian and was used as the main reference book by the chief astronomers and timekeepers of the Ottoman State for their astrological and astronomical Born Bursa, (Turkey), 1689 studies. ˁAbbās Wasīm Efendi worked on this book beginning Died Istanbul, (Turkey), 1760 in 1745, at the request of the historian and astronomer Aḥmad Miṣrī, who convinced him of the importance of a Turkish ˁAbbās Wasīm Efendi was a scholar who made many valuable translation. Upon completion, ˁAbbās Wasīm Effendi presented contributions to Ottoman astronomy. These included writing a it to the Ottoman Sultan Maḥmūd I (reigned: 1730–1754). His Turkish commentary on the famous astronomical handbook (Zīj) commentary is written in clear Turkish, in the same style of of Ulugh Beg as well as translating ˁAbd al-ˁAlī al-Bīrjandī’s Mīram Chelebī’s (d. 1525) commentary on the same work. work on solar and lunar eclipses into Turkish. In addition to The worked examples given in the book are all based onˁ Abbās being an astronomer, he was also a physician, calligrapher, and Wasīm Effendi’s own calculations for the longitude and latitude a poet, and he was a member of the Khalwatiyya and Qādiriyya of Istanbul. He includes findings from ancient Turkish, Hebrew, religious orders. Besides Turkish, ˁAbbās Wasīm Efendi knew and Roman Calendars, which were not in the original. He also a number of languages that included Arabic, Persian, Latin, explains Ulugh Beg’s method for finding the sine of one degree, French, and ancient Greek. which was based upon the work of Jamshīd al-Kāshī. -

Library of Richard Weiss Astronomy Chemistry Mathematics Mineralogy Physics Part II

JEFF WEBER RARE BOOKS 1815 Oak Ave, Carlsbad CA 92008 Phone: 323 333 4140 [email protected] MEMBER: ABAA ILAB From the Library oF richard Weiss Astronomy Chemistry Mathematics Mineralogy Physics part II NOTE: See PICTURES for all items available on-line at: WeberRareBooks.com [284] 140 JEFF WEBER RARE BOOKS First English Edition 284. AGRICOLA, Georgius (1494-1555); HOOVER, Herbert [trans.] (1874- 1964); HOOVER, Lou Henry (1874-1944). De Re Metallica. Translated from the First Latin Edition of 1556 with Biographical Introduction, Annotations and Appendices upon the Development of Mining Methods, Metallurgical Processes, Geology, Mineralogy & Mining Law from the earliest times to the 16th Century. London: The Mining Magazine, 1912. ¶ Thick folio. [2], xxxi, [1], 640 pp. Copiously illustrated with engraved plates and figures. Original vellum over boards. Bookplate of Marcus Crahan, illegible ownership inscription on front endpaper. Fine. SW1291 $ 750 First edition in English of this classic of technology. Limited edition of 1476 copies. The valuable bibliographical information provided in the introduction and appendices is not widely appreciated, but probably should be. Notable not only for the clarity of its language, but for its extensive footnotes, which identify the numerous classical references to mining and metals. In exceptionally good condition. Provenance: Marcus Crahan was the Los Angeles County coroner, and a remarkable book collector of the history of gastronomy. He also enjoyed fine printing and bookbinding (for he was himself an amateur binder). ☼ Duveen, Bibliotheca Alchemica et Chemica, p. 5; Honeyman I, 36; Hoover 28; Norman 21; Printing and the Mind of Man 69. 141 JEFF WEBER RARE BOOKS Lunar and Planetary Theories 285. -

Cleveland Abbe and American Meteorology, 1871-1901

CLEVELAND ABBE AND AMERICAN METEOROLOGY, 1871-1901 BY EDMUND P. WILLIS AND WILLIAM H. HOOKE A reexamination and reappraisal of Cleveland Abbe's role in the development of meteorological science and services is made. "[to Abbe] we are indebted for the very existence of the Weather Bureau" —BRIGADIER GENERAL WILLIAM B. HAZEN (testimony before Congress, 1886) n 1871 Cleveland Abbe (1838-1916) took a risk and joined the U.S. Government s completely new weather service as its first chief meteorologist. This move took him from the well-established field of astronomy into what was then a developmental science. He brought to the endeavor scientific rigor and a far-reaching vision of worldwide scientific cooperation. From the outset he focused on two ma- jor scientific goals: the optimization of the weather service, and the study and advocacy of theoretical meteorology. As he tutored the neophytes at the headquarters in Washington, D.C., he symbolized for them what they might achieve as meteorologists (Reingold 1964). During the formative years of gov- ernment weather services, he fostered, and in some respects embodied, the essential linkage between institutional and theoretical development (Fleming 1990). In that role he came to recognize the three dimensions of meteorology: forecasting, climatol- ogy, and physical theory. He brought together his insights in 1901. In a comprehensive scientific paper, published in the Monthly Weather Review (MWR), he argued against long-range weather forecasts based on Fig. I. Cleveland Abbe (1838-1916). empirical methodology, by which he meant forecasts AMERICAN METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY MARCH 2006 BAHS* | 315 Unauthenticated | Downloaded 10/03/21 10:15 PM UTC that are "generalizations based upon observations" In spite of a promising start, his focus on climatology without the benefit of physical theories (Abbe 1901). -

Prepared by the Home Secretary the Autumn Meetingof the Academywas

REPORT OF THE AUTUMN MEETING 753 Report of the committee appointed by the National Academy of Sciences upon the inaugu- ration of a forest policy for the forested lands of the United States to the Secretary of the Interior, May 1, 1897. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1897. Pp. 1-47. Fifty-eighth Congress, 3d Session. Senate Doc. no. 145. Report by committee appointed by Academy to consider desirability of instituting scientific explorations of Philip- pine Islands. Pp. 1-22. 8°. Ordered printed, February 7, 1905. Sixtieth Congress, 2d Session. House of Representatives, Doc. no. 1337. Conduct of scientific work under United States Government. Message from the President of the United States, transmitting report of the National Academy of Sciedces relating to the conduct of the scientific work under the United States Government. Pp. 1-5. 8°. Ordered printed, January 18, 1909. ANNUAL REPORTS For Year Pages Printed For Year Pages Prnnted For Year Pages Printed 1863 118 1864 1881 1899 39 1900 1864 15 1865 1882 1900 37 1901 1865 1883 145 1884 1901 39 1902 1866 95 1867 1884 69 1885 1902 41 1903 1867 44 1868 1885, 101 1886 1903 39 1904 1868 1886 1904 57 1905 1869 1887 55 1888 1905 41 1906 1870 1888 41 1890 1906 43 1907 1871 1889 69 1891 1907 40 1908 .1872 1890 36 1891 1908 111 1909 1873 1891 39 1892 1909 43 1910 1874 1892 39 1893 1910 48 1911 1875 1893 47 1895 1911 55 1912 1876 1894 43 1895 1912 54 1913 1877 1895 51 1896 1913 112 1914 1878 25 1879 1896 39 1897 1914 90 1915 1879 22 1880 1897 93 1898 1915 74 1916 1880 1898 33 1899 1916 94 1917 REPORT OF THE AUTUMN MEETING Prepared by the Home Secretary The Autumn Meeting of the Academy was held in the Engineering Building of the.University of Pennsylvania at Phijadelphia, on November 20 and 21, 1917. -

History of Science Society Annual Meeting Cleveland, 3-6 November

History of Science Society Annual Meeting Cleveland, 3-6 November Session Abstracts Alphabetized by Session Title. Abstracts only available for organized sessions. Paper abstracts begin on page 23. Aesthetics and Politics: Towards Building Relationships between Media Studies and History of Science Abstract: This session will explore the political implications of aesthetics with an eye towards furthering the ongoing conversation between media studies and the history of science. Each of these papers engages with a central moment or theme in the history of science and technology and analyses it through an interdisciplinary framework. Our papers are all linked by a central concern with the relationship between the embodied self and political and socials structures dominated by scientific and technological rhetoric. We all explore issues of design, the visual, images, and imagination in order to begin to build a new methodology around mediation, politics, and aesthetics in the scientific imaginary. All at Sea? Oceanography and Geopolitics in the Twentieth Century Abstract: Inspired by Ronald Doel's call for more critical analysis of the links between physical scientists and 'environmental' knowledge, specifically the desire to control as well as observe the earth, this panel examines the interface between oceanographers and the political/economic contexts in which they worked during the twentieth century. Lajus uses the under-examined history of Soviet oceanography to explore the role of major international projects -- notably the 1932-33 International Polar Year – in shaping a disciplinary community, as oceanography became an asset to state action in Arctic environments. Roberts argues that the oceanographic career of Hans Pettersson (best known to historians of science for his work in nuclear physics) reveals that the massive influx of money during the 1950s produced new geographies of patronage, most notably international networks with heavy American state influence. -

“Not As a Thing for the Moment, but for All Time”

“ N o t A s A t h i N g f o r t h e M o M e N t, B u t f o r A l l t i M e ” t h e u N iversity of Chi ca g o an d i t s h i s t o r i e s J o h n W . B o y e r o C C A s i o na l p A p e r s o N h i g h e r e d u ca t i o N X X XXt h e C o l l e g e o f t h e u N iversity of C h i ca g o Galusha Anderson, President, 1878 – 1885 An oil portrait of Galusha Anderson hangs in the Common Room in Swift Hall at the University of Chicago. Anderson served as Professor in the University of Chicago Divinity School after the re-founding of the University, retiring in 1903. His career embodies the continuous tradition of the two institutions bearing the name of the University of Chicago. “ N o t A s A t h i N g f o r t h e M o M e N t , But for All t i M e ” The University of Chicago and Its Histories his academic year begins with a College student body of slightly over 5,200 and a first-year class of 1,386 T students plus 56 transfer students. These numbers are important in several ways — some apparent and some not so apparent.