ˁabbās Wasīm Efendi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Chapter (PDF)

LIST OF COLLABORATORS: EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, BENJAMIN E. SMITH, A.M., L.H.D. EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTORS, CLEVELAND ABBE, A.M., LL.D. JOHN MASON CLARKE, Ph.D., LL.D. Professor of Meteorology, United States New York State Geologist and Paleon- WILLIAM HALLOCK, Ph.D. Weather Bureau. tologist; Director of the State Museum Professor of Physics in Columbia and of the Scicncc Division of the De- University. M ctcorology. partment of Education of the State of New York. Color Photography. LIBERTY HYDE BAILEY, M.S., LL.D. Paleontology; Stratigraphy. Director of the New York State College GEORGE BRUCE HALSTED, Ph.D. of Agriculture, Cornell University. Professor of Mathematics in the Horticulture. FREDERICK VERNON COVILLE, A.B. Colorado State Normal School. Curator of the United States National Mathematics. ITcrbariu m. ADOLPH FRANCIS BANDELIER, Systematic and Economic Botany. Lecturer on American Archaeology in FRANK E. HOBBS, Columbia University. LIEUTENANT-COLONEL, ORDNANCE DEPARTMENT, South American Ethnology and STEWART CULIN. UNITED STATES ARMY. Archeology. Commanding Officer of the Rock Island Numismatics. Arsenal. Ordnajice; Military Arms; Explo- EDWIN ATLEE BARBER, A.M., Ph.D. sives. Director of the Museum of the Pennsylvania EDWARD SALISBURY DANA, Museum and School of Industrial Art. A.M., Ph.D. Ceramics; Glass-making. Professor of Physics and Curator of LELAND OSSIAN HOWARD, Mineralogy in Yale University. M.S., Ph.D. Mineralogy. Chief Entomologist of the United States CHARLES BARNARD. Department of Agriculture; Honorary Curator of the United States National Museum; Consulting Entomologist of Tools and Appliances. the United States Public Health and WILLIAM MORRIS DAVIS, Marine Hospital Service. M.E., Sc.D., Ph.D. -

5. Cleveland Abbe and the Birth of the National Weather Service, 1870

Proceedings of the International Commission on History of Meteorology 1.1 (2004) 5. Cleveland Abbe and the Birth of the National Weather Service, 1870-1891 Edmund P. Willis Kinsale Research Alexandria, Virginia, USA and William H. Hooke American Meteorological Society Washington, DC, USA Cleveland Abbe (1838-1916) made substantial scientific and administrative contributions to nascent national weather services during their first twenty years under the aegis of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Prior studies of the Signal Service, however, give short shrift to Abbe’s work. In particular most accounts barely mention Abbe’s scientific endeavors during the initial decade, 1871-1880.1 This paper examines three aspects of Abbe’s career: (a) his background; (b) the science he initiated; and (c) his administrative accomplishments. Two conclusions emerge: first, Abbe initiated significant, broad-based scientific research, beginning in the 1870s; and second, Abbe’s scientific contributions deserve recognition for their part in the evolution of 19th century meteorology. Abbe shared the background and many of the characteristics of American scientists in the 19th century. His father, George W. Abbe, was a New York merchant of New England ancestry. His parents raised him in the Baptist tradition of service and respect for others. He took his undergraduate degree in 1857 from the Free Academy, forerunner of the City College of New York, where he demonstrated an interest in meteorology. He went on to study astronomy in 1859 at the University of Michigan, and began work with the U. S. Coast Survey in 1860 at its office in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There he acquired a desire for graduate study abroad. -

History of Meteorology 5 (2009) 126

History of Meteorology 5 (2009) 126 The International Bibliography of Meteorology: Revisiting a nineteenth-century classic James Rodger Fleming Science, Technology and Society Program Colby College, Waterville, Maine, USA [email protected] The International Bibliography of Meteorology, published in 1994, is a new edition of a nineteenth century bibliography supervised by Oliver L. Fassig and issued in four volumes by the U.S. Army Signal Corps between 1889 and 1891. The original volumes are not easy to find, read, or use. They were lithographed in small quantities on acidic paper. Only a few copies are still in existence and, for the most part, are now in poor condition. The 1994 edition, prepared by Roy E. Goodman and me, is still in print and is available in 120 research libraries and via interlibrary loan. This essay is a reintroduction to the history and importance of the project. A perusal of the bibliography is a humbling experience in the richness, breadth and value of past observations. The volumes contain over 16,000 items on temperature, moisture, winds, and storms, “from the beginning of printing to 1889,” with two-thirds of the entries in languages other than English and ten percent of the entries dated before 1750. Meteorological and Geo-astrophysical Abstracts called the effort “the most ambitious and intensive bibliographic project ever undertaken in meteorology.”1 Documented here are accounts of environmental changes prior to 1890, temperature and rainfall records, descriptions of hurricanes, snowstorms, shipwrecks, acid rain events, and numerous other topics of interest to researchers in such diverse fields as agriculture, forestry, exploration, geography, hydrology, oceanography, geology and geophysics, maritime history, environmental history, literature and folklore. -

Catalogue #19

Back of Beyond Books proudly releases Catalogue #19. We continue to feature books and ephemera from the American West but you’ll also find numerous pages of Americana, Travel and Photographic material along with Explora- tion, Mining and Native Americana. We’ve also picked up small collections of Poetry and Art Books which have been fun to catalogue. Perhaps my favorite genre of Catalogue #19 are the 21 Promotional items from western states and communities. These colorful pamphlets, mostly from the early 20th century, would make any Chamber of Commerce proud. It’s always interesting to see what items sell quickly in each catalogue. I of- ten guess wrong so I’ll leave the decisions up to you. Several items of note, however, include: The best association copy known of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian--inscribed to Edward Abbey, a beautifully bright advertising poster for the ‘Field Self Discharging Rake’, a scarce promotional for the Salt River Valley of Arizona, a full-plate tintype from Volcano, California, and six large format albumen photographs depicting archaeological sites of Arizona and New Mexico by John K. Hillers. I’m also taken with the striking and rare Broadside for the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, the very clean re- view copy of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and the atlas from the Pike Expe- dition published in 1810. Thanks to my staff at the store for working around the piles and boxes of books. If you’re ever in Moab our shop is open daily; please stop in. Sophie Tomkiewicz used the skills she learned at the Colorado Rare Books School in developing Catalogue #19 and Eric Trenbeath is our designer. -

Eossibilitvof Your Going Far Wrong If

In th<* picturesque b^roujrh of Bristol on the "res* nt> drlc^St*- from Wm>hin?toa to AX jfSPKDITION AKTKR T11K SIN. * Africa*. < )f tbf mulrr* WIVES OF WELL-KNOWN MEN. batiks or territory j binam-n, the Delaware ;u the fertile the Conferees. but. his be¬ a. wi.h 'U< . 011. I ". and i^-riraltur.il FROM THE NEW STATES. Fifty-fir,it territory Eumpua tongu al:. xwjit A. Sri.town*. ^ suburban county ot Bucks in Pennsylvania coming a state. bo Kive»u;> that position to rep¬ The I»cnsacola's Trl>> to the African believe. o( tlie Uurt>Kf< of Turkey and Fin¬ TMi. \\!X: AkU IJQron MIIICHAHT. la a a wocwU'ii with resent. in imrt. the new state spaciou> old-timo mansion of Washington in Cornt land. are spoken among the sailors. If Sunday Uu take* loairMloi of kia many interesting aud sometimessad experience*! the United States Senate. morning in a pleasant one. an-l instead of at¬ Some Ladies Who Are Prominent in of this was MAGNIFICENT NEW STORES AND family history. For many years Some I SEMATOB SQVIRK. scientists who jtovkbed to sea sickness. tending church, where few sailors are to be the home of F. Gi'lke-on. in the of the Senators Who we roam about tnc deck of the WISE VAII.TR. Benjamin Represent His colleague. Watson C. is a native life ON BOARD A MAN-OF-WAR DESCRIBED BT found, upper Washington Society. restoration of rule the influence of Squire, shiD, we shall see men at cards, bask¬ 1500and 170V Banna. -

Tradition Versus History in American Meteorology

FEBRUARY,1930 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW 65 TRADITION VERSUS HISTORY IN AMERICAN METEOROLOGY ERICR. MILLER The claims of the biographers of Matthew Font,aine The incident referred to in the foregoing quotat)ions, Maury that he was the founder of our national weather the initiation of meteorological telegrams for the benefit of service have been discounted by Charles F. Brooks (l), commerce and navigation as a function of the Signal but in trying to avoid Scylla, Brooks runs into Charybdis Service of the Army, is easily accessible in the official when lie says that Cleveland Abbe’s forec,asting service at records. Cincinnati grew into the national weather servke.’ A memorial written by Increase A. Lapham, of Mil- Inasmuch as the intere.st in the history of science and wauke,e, Wis., on December 8, 1869, and addressed to in the lives of scientists is now inc.reasing, it may be of Gen. Halbert E. Paine, Member of Congress from the interest to writers of test,books and of enayclopedias, t’o congressional district in which Milwaukae is located, learn of other c,lrtirns that have no more basis than those induced Paine to prepare a bill (H. R. 603) whic.h he just ment,ioned. The following have been estracted from int,roduced on December 16, 1869. Paine obtained let- sources that would naturally be regarded as of the highest t,ers in support of his bill from the following persons: authority: J. K. Barnes, Surgeon General, United States Army. James Pollard Espy “organized a sen7ic.e of daily Joseph Henry, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. -

Hclassification

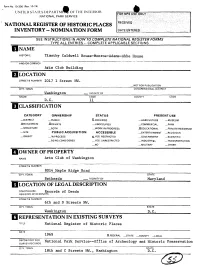

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNiTEDSTATES DEPARTMlW Oh THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Timothy Caldwell House-Monroe-Adams-Abbe House AND/OR COMMON Arts Club Building LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER 2017 I Street NW, —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Washington _ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE D.C. 11 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) _XPRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -XEDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED — INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Arts Club of Washington STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Maryland LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, Records of Deeds REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. STREET & NUMBER 6th and D Streets NW. CITY, TOWN STATE Washington D.C. 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE National Register of Historic Places DATE 1969 XFEDERAL _STATE _COUNTY __LOCAL DEPOSITORYFOR National Park Service—Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE 18th and C Streets NW., Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^.EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED ^.UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The following architectural description is taken from the National Register Nomination Form for 2017 I Street. The form was prepared in 1969 and there have been no significant changes to the property since then. -

Miscellaneous Manuscripts and Books, Circa 1854-1962

Miscellaneous Manuscripts and Books, circa 1854-1962 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Miscellaneous Manuscripts and Books https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_303964 Collection Overview Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C., [email protected] Title: Miscellaneous Manuscripts and Books Identifier: Accession T90124 Date: circa 1854-1962 Extent: 2 cu. ft. (2 record storage boxes) Creator:: Smithsonian Institution. Libraries Language: English Administrative Information Prefered Citation Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession T90124, Smithsonian Institution, Libraries, Miscellaneous Manuscripts and Books Descriptive Entry This accession consists of miscellaneous publications, notes, drafts, maps and other related materials. Authors and correspondents include Spencer -

The Historic “Aerodrome A”

Politically Incorrect The Flights and Fights Involving the Langley Aerodrome By Nick Engler As morning dawned on 28 May 1914, the “Aerodrome A” perched like a giant dragonfly on the edge of Lake Keuka, surrounded by journalists, photographers, even a videographer. Members of the scientific elite and Washington DC power structure were also there, among them Charles Doolittle Walcott, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and Albert Zahm, the director of the recently reopened Langley Aerodynamical Laboratory. They carefully spun the event for the media, explaining why they were attempting to fly the infamous Langley Aerodrome eleven years after two highly-publicized, unsuccessful, and nearly- catastrophic launch attempts. A cool breeze blew down the lake, gently rocking the four tandem wings that sprouted from the Aerodrome’s central framework. It was time to go. As the sun crept higher in the sky the winds would kick up. With a pronounced 12-degree dihedral between the pairs of 22-foot wings, even a modest crosswind could flip the old aircraft if it got under a wing. Workmen from the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company of Hammondsport, New York lined up along the pontoons and outriggers recently added to the airframe. They lifted the half-ton aircraft a foot or so above the ramp, duck-walked it into the water and turned it into the wind. 1 Glenn Curtiss waded out, stepped onto the braces between the forward pontoons and climbed into the nacelle that hung beneath the framework. He settled into the cockpit and tested the familiar Curtiss controls – wheel, post and shoulder yoke borrowed from one of his early pushers.1 This system had replaced the dual trim wheels that had steered the original Aerodrome. -

Harqua Hala Letters

BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT ARIZONA , I' .. -- Harqua Hala Letters The story of Arizona's forgotten Smithsonian Observatory Pieter Burggraaf CULTURAL RESOURCE SERIES No. 9 1996 HARQUA HALA LETTERS The story of Arizona's forgotten 1920's Smithsonian Institution Observatory By Pieter Burggraaf Cultural Resources Series Monograph No.9 Published by the Arizona State Office of the Bureau of Land Management 3707 N. 7th. Street Phoenix, Arizona 85014 May 1996 Contents Preface v Introduction IX 1. The Legacy 2. Finding a Mountain 9 3. Moving In 17 4. Aiming at the Sun 25 5. Near Disaster 31 6. Aldrich Returns 37 7. From the Comfort ofL.A. 49 8. Moore's Attitude Arrives 59 9. Troubles With Knight 67 10. After One Year 77 11. A Voice From Stockton 89 12. Taking Care of Lightning 97 13. Plans for Continued Work 107 14. Settling Down Until 1925 115 15. Finally, Good Results 125 11 HARQUA HALA LETTERS 16. A Wire to Wenden 133 17. Ready for a Real Test 141 18. Changing the Staff 149 19. Paul and Bill 157 20. The Moores Return 165 21. Moore Versus Greeley 175 22. Round Two 183 23. Between Assistants 191 24. Worthing Spits! 199 25. Changes in the Wind 205 26. Pushing for CalifornIa 213 27. Good-by Harqua Hala 221 28. Epilogue 227 29. Period Photographs 233 List of Photographs Harqua Hala Mountain from the business section of Wenden, Arizona 234 Harqua Hala field station on August 26, 1920 234 Charles Abbot and others packing equipment to summit 235 Fred Greeley and Loyal Aldrich at Harqua Hala field station 235 The observing equipment at Harqua Hala field station 236 Weather damaged field station circa December 1920 236 Dr. -

Records, 1890-1922

Records, 1890-1922 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Series 1: GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE AND ACCOUNTING RECORDS, 1890, 1898-1920................................................................................................................. 3 Series 2: PUBLICATIONS........................................................................................ 4 Series 3: NEWS CLIPPINGS................................................................................... 5 Records https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_217624 Collection Overview Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C., [email protected] Title: Records Identifier: Record Unit 7471 Date: -

Edison Pettit Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf9q2nb3w2 No online items Edison Pettit Papers: Finding Aid Processed by Ronald S. Brashear in March 1998. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 1998 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Edison Pettit Papers: Finding Aid mssPettit papers 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Edison Pettit Papers Dates (inclusive): 1920-1969 Collection Number: mssPettit papers Creator: Pettit, Edison, 1889-1962. Extent: 6 boxes (3,100 pieces) Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of astronomer Edison Pettit (1889-1962), who was on the staff of the Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories. The correspondence is chiefly with other astronomers in the United States and deals with astronomy in general including Pettit's work at Mount Wilson, telescopes, and ultraviolet light research. The rest of the collection is made up of manuscripts, notes, notebooks and printed items. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher.