The First American Doctorate in Meteorology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Chapter (PDF)

LIST OF COLLABORATORS: EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, BENJAMIN E. SMITH, A.M., L.H.D. EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTORS, CLEVELAND ABBE, A.M., LL.D. JOHN MASON CLARKE, Ph.D., LL.D. Professor of Meteorology, United States New York State Geologist and Paleon- WILLIAM HALLOCK, Ph.D. Weather Bureau. tologist; Director of the State Museum Professor of Physics in Columbia and of the Scicncc Division of the De- University. M ctcorology. partment of Education of the State of New York. Color Photography. LIBERTY HYDE BAILEY, M.S., LL.D. Paleontology; Stratigraphy. Director of the New York State College GEORGE BRUCE HALSTED, Ph.D. of Agriculture, Cornell University. Professor of Mathematics in the Horticulture. FREDERICK VERNON COVILLE, A.B. Colorado State Normal School. Curator of the United States National Mathematics. ITcrbariu m. ADOLPH FRANCIS BANDELIER, Systematic and Economic Botany. Lecturer on American Archaeology in FRANK E. HOBBS, Columbia University. LIEUTENANT-COLONEL, ORDNANCE DEPARTMENT, South American Ethnology and STEWART CULIN. UNITED STATES ARMY. Archeology. Commanding Officer of the Rock Island Numismatics. Arsenal. Ordnajice; Military Arms; Explo- EDWIN ATLEE BARBER, A.M., Ph.D. sives. Director of the Museum of the Pennsylvania EDWARD SALISBURY DANA, Museum and School of Industrial Art. A.M., Ph.D. Ceramics; Glass-making. Professor of Physics and Curator of LELAND OSSIAN HOWARD, Mineralogy in Yale University. M.S., Ph.D. Mineralogy. Chief Entomologist of the United States CHARLES BARNARD. Department of Agriculture; Honorary Curator of the United States National Museum; Consulting Entomologist of Tools and Appliances. the United States Public Health and WILLIAM MORRIS DAVIS, Marine Hospital Service. M.E., Sc.D., Ph.D. -

5. Cleveland Abbe and the Birth of the National Weather Service, 1870

Proceedings of the International Commission on History of Meteorology 1.1 (2004) 5. Cleveland Abbe and the Birth of the National Weather Service, 1870-1891 Edmund P. Willis Kinsale Research Alexandria, Virginia, USA and William H. Hooke American Meteorological Society Washington, DC, USA Cleveland Abbe (1838-1916) made substantial scientific and administrative contributions to nascent national weather services during their first twenty years under the aegis of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Prior studies of the Signal Service, however, give short shrift to Abbe’s work. In particular most accounts barely mention Abbe’s scientific endeavors during the initial decade, 1871-1880.1 This paper examines three aspects of Abbe’s career: (a) his background; (b) the science he initiated; and (c) his administrative accomplishments. Two conclusions emerge: first, Abbe initiated significant, broad-based scientific research, beginning in the 1870s; and second, Abbe’s scientific contributions deserve recognition for their part in the evolution of 19th century meteorology. Abbe shared the background and many of the characteristics of American scientists in the 19th century. His father, George W. Abbe, was a New York merchant of New England ancestry. His parents raised him in the Baptist tradition of service and respect for others. He took his undergraduate degree in 1857 from the Free Academy, forerunner of the City College of New York, where he demonstrated an interest in meteorology. He went on to study astronomy in 1859 at the University of Michigan, and began work with the U. S. Coast Survey in 1860 at its office in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There he acquired a desire for graduate study abroad. -

History of Meteorology 5 (2009) 126

History of Meteorology 5 (2009) 126 The International Bibliography of Meteorology: Revisiting a nineteenth-century classic James Rodger Fleming Science, Technology and Society Program Colby College, Waterville, Maine, USA [email protected] The International Bibliography of Meteorology, published in 1994, is a new edition of a nineteenth century bibliography supervised by Oliver L. Fassig and issued in four volumes by the U.S. Army Signal Corps between 1889 and 1891. The original volumes are not easy to find, read, or use. They were lithographed in small quantities on acidic paper. Only a few copies are still in existence and, for the most part, are now in poor condition. The 1994 edition, prepared by Roy E. Goodman and me, is still in print and is available in 120 research libraries and via interlibrary loan. This essay is a reintroduction to the history and importance of the project. A perusal of the bibliography is a humbling experience in the richness, breadth and value of past observations. The volumes contain over 16,000 items on temperature, moisture, winds, and storms, “from the beginning of printing to 1889,” with two-thirds of the entries in languages other than English and ten percent of the entries dated before 1750. Meteorological and Geo-astrophysical Abstracts called the effort “the most ambitious and intensive bibliographic project ever undertaken in meteorology.”1 Documented here are accounts of environmental changes prior to 1890, temperature and rainfall records, descriptions of hurricanes, snowstorms, shipwrecks, acid rain events, and numerous other topics of interest to researchers in such diverse fields as agriculture, forestry, exploration, geography, hydrology, oceanography, geology and geophysics, maritime history, environmental history, literature and folklore. -

Catalogue #19

Back of Beyond Books proudly releases Catalogue #19. We continue to feature books and ephemera from the American West but you’ll also find numerous pages of Americana, Travel and Photographic material along with Explora- tion, Mining and Native Americana. We’ve also picked up small collections of Poetry and Art Books which have been fun to catalogue. Perhaps my favorite genre of Catalogue #19 are the 21 Promotional items from western states and communities. These colorful pamphlets, mostly from the early 20th century, would make any Chamber of Commerce proud. It’s always interesting to see what items sell quickly in each catalogue. I of- ten guess wrong so I’ll leave the decisions up to you. Several items of note, however, include: The best association copy known of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian--inscribed to Edward Abbey, a beautifully bright advertising poster for the ‘Field Self Discharging Rake’, a scarce promotional for the Salt River Valley of Arizona, a full-plate tintype from Volcano, California, and six large format albumen photographs depicting archaeological sites of Arizona and New Mexico by John K. Hillers. I’m also taken with the striking and rare Broadside for the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, the very clean re- view copy of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and the atlas from the Pike Expe- dition published in 1810. Thanks to my staff at the store for working around the piles and boxes of books. If you’re ever in Moab our shop is open daily; please stop in. Sophie Tomkiewicz used the skills she learned at the Colorado Rare Books School in developing Catalogue #19 and Eric Trenbeath is our designer. -

Professionalizing Science and Engineering Education in Late- Nineteenth Century America Paul Nienkamp Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2008 A culture of technical knowledge: professionalizing science and engineering education in late- nineteenth century America Paul Nienkamp Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Other History Commons, Science and Mathematics Education Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Nienkamp, Paul, "A culture of technical knowledge: professionalizing science and engineering education in late-nineteenth century America" (2008). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15820. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15820 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A culture of technical knowledge: Professionalizing science and engineering education in late-nineteenth century America by Paul Nienkamp A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: History of Technology and Science Program of Study Committee: Amy Bix, Co-major Professor Alan I Marcus, Co-major Professor Hamilton Cravens Christopher Curtis Charles Dobbs Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2008 Copyright © Paul Nienkamp, 2008. All rights reserved. 3316176 3316176 2008 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ABSTRACT v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION – SETTING THE STAGE FOR NINETEENTH CENTURY ENGINEERING EDUCATION 1 CHAPTER 2. EDUCATION AND ENGINEERING IN THE AMERICAN EAST 15 The Rise of Eastern Technical Schools 16 Philosophies of Education 21 Robert Thurston’s System of Engineering Education 36 CHAPTER 3. -

Forestry Education at the University of California: the First Fifty Years

fORESTRY EDUCRTIOfl T THE UflIVERSITY Of CALIFORflffl The first fifty Years PAUL CASAMAJOR, Editor Published by the California Alumni Foresters Berkeley, California 1965 fOEUJOD T1HEhistory of an educational institution is peculiarly that of the men who made it and of the men it has helped tomake. This books tells the story of the School of Forestry at the University of California in such terms. The end of the first 50 years oi forestry education at Berkeley pro ides a unique moment to look back at what has beenachieved. A remarkable number of those who occupied key roles in establishing the forestry cur- riculum are with us today to throw the light of personal recollection and insight on these five decades. In addition, time has already given perspective to the accomplishments of many graduates. The School owes much to the California Alumni Foresters Association for their interest in seizing this opportunity. Without the initiative and sustained effort that the alunmi gave to the task, the opportunity would have been lost and the School would have been denied a valuable recapitulation of its past. Although this book is called a history, this name may be both unfair and misleading. If it were about an individual instead of an institution it might better be called a personal memoir. Those who have been most con- cerned with the task of writing it have perhaps been too close to the School to provide objective history. But if anything is lost on this score, it is more than regained by the personalized nature of the account. -

An Improbable Venture

AN IMPROBABLE VENTURE A HISTORY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO NANCY SCOTT ANDERSON THE UCSD PRESS LA JOLLA, CALIFORNIA © 1993 by The Regents of the University of California and Nancy Scott Anderson All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Anderson, Nancy Scott. An improbable venture: a history of the University of California, San Diego/ Nancy Scott Anderson 302 p. (not including index) Includes bibliographical references (p. 263-302) and index 1. University of California, San Diego—History. 2. Universities and colleges—California—San Diego. I. University of California, San Diego LD781.S2A65 1993 93-61345 Text typeset in 10/14 pt. Goudy by Prepress Services, University of California, San Diego. Printed and bound by Graphics and Reproduction Services, University of California, San Diego. Cover designed by the Publications Office of University Communications, University of California, San Diego. CONTENTS Foreword.................................................................................................................i Preface.........................................................................................................................v Introduction: The Model and Its Mechanism ............................................................... 1 Chapter One: Ocean Origins ...................................................................................... 15 Chapter Two: A Cathedral on a Bluff ......................................................................... 37 Chapter Three: -

Eossibilitvof Your Going Far Wrong If

In th<* picturesque b^roujrh of Bristol on the "res* nt> drlc^St*- from Wm>hin?toa to AX jfSPKDITION AKTKR T11K SIN. * Africa*. < )f tbf mulrr* WIVES OF WELL-KNOWN MEN. batiks or territory j binam-n, the Delaware ;u the fertile the Conferees. but. his be¬ a. wi.h 'U< . 011. I ". and i^-riraltur.il FROM THE NEW STATES. Fifty-fir,it territory Eumpua tongu al:. xwjit A. Sri.town*. ^ suburban county ot Bucks in Pennsylvania coming a state. bo Kive»u;> that position to rep¬ The I»cnsacola's Trl>> to the African believe. o( tlie Uurt>Kf< of Turkey and Fin¬ TMi. \\!X: AkU IJQron MIIICHAHT. la a a wocwU'ii with resent. in imrt. the new state spaciou> old-timo mansion of Washington in Cornt land. are spoken among the sailors. If Sunday Uu take* loairMloi of kia many interesting aud sometimessad experience*! the United States Senate. morning in a pleasant one. an-l instead of at¬ Some Ladies Who Are Prominent in of this was MAGNIFICENT NEW STORES AND family history. For many years Some I SEMATOB SQVIRK. scientists who jtovkbed to sea sickness. tending church, where few sailors are to be the home of F. Gi'lke-on. in the of the Senators Who we roam about tnc deck of the WISE VAII.TR. Benjamin Represent His colleague. Watson C. is a native life ON BOARD A MAN-OF-WAR DESCRIBED BT found, upper Washington Society. restoration of rule the influence of Squire, shiD, we shall see men at cards, bask¬ 1500and 170V Banna. -

Tradition Versus History in American Meteorology

FEBRUARY,1930 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW 65 TRADITION VERSUS HISTORY IN AMERICAN METEOROLOGY ERICR. MILLER The claims of the biographers of Matthew Font,aine The incident referred to in the foregoing quotat)ions, Maury that he was the founder of our national weather the initiation of meteorological telegrams for the benefit of service have been discounted by Charles F. Brooks (l), commerce and navigation as a function of the Signal but in trying to avoid Scylla, Brooks runs into Charybdis Service of the Army, is easily accessible in the official when lie says that Cleveland Abbe’s forec,asting service at records. Cincinnati grew into the national weather servke.’ A memorial written by Increase A. Lapham, of Mil- Inasmuch as the intere.st in the history of science and wauke,e, Wis., on December 8, 1869, and addressed to in the lives of scientists is now inc.reasing, it may be of Gen. Halbert E. Paine, Member of Congress from the interest to writers of test,books and of enayclopedias, t’o congressional district in which Milwaukae is located, learn of other c,lrtirns that have no more basis than those induced Paine to prepare a bill (H. R. 603) whic.h he just ment,ioned. The following have been estracted from int,roduced on December 16, 1869. Paine obtained let- sources that would naturally be regarded as of the highest t,ers in support of his bill from the following persons: authority: J. K. Barnes, Surgeon General, United States Army. James Pollard Espy “organized a sen7ic.e of daily Joseph Henry, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. -

Hclassification

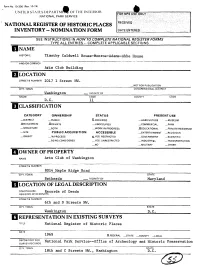

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNiTEDSTATES DEPARTMlW Oh THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Timothy Caldwell House-Monroe-Adams-Abbe House AND/OR COMMON Arts Club Building LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER 2017 I Street NW, —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Washington _ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE D.C. 11 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) _XPRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -XEDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED — INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Arts Club of Washington STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Maryland LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, Records of Deeds REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. STREET & NUMBER 6th and D Streets NW. CITY, TOWN STATE Washington D.C. 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE National Register of Historic Places DATE 1969 XFEDERAL _STATE _COUNTY __LOCAL DEPOSITORYFOR National Park Service—Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE 18th and C Streets NW., Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^.EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED ^.UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The following architectural description is taken from the National Register Nomination Form for 2017 I Street. The form was prepared in 1969 and there have been no significant changes to the property since then. -

UC Berkeley Research and Occasional Papers Series

UC Berkeley Research and Occasional Papers Series Title CLARK KERR: TRIUMPHS AND TURMOIL Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7192n8sb Author Gardner, David P Publication Date 2012-07-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Research & Occasional Paper Series: CSHE.10.12 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY http://cshe.berkeley.edu/ CLARK KERR: TRIUMPHS AND TURMOIL* July 2012 David P. Gardner President Emeritus, University of California and University of Utah Copyright 2012 David P. Gardner, all rights reserved. ABSTRACT This paper is a personal recollection of Clark Kerr and his presidency of the University of California by a friend of 43 years, not from a distance, but as a former student, colleague and successor president of the University. It is also a summary remembrance of the contributions made by his three most influential predecessors. These three presidents: Gilman (1872-75), Wheeler (1899-1919), and Sproul (1930-1958), essentially defined the trail of history that led to and helped shape Kerr’s own presidency (1958-1967). The principal focus of this paper is Kerr’s beliefs, values, style, personality, ways of working, priorities and life-experiences that so informed his professional and personal lives. Few such private persons have held such a public position as that of president of the University of California. The interplay between the man and his duties helps one better to understand and more deeply to appreciate Kerr’s remarkable accomplishments and the triumphs and turmoil that defined both his presidency and legacy alike. The University of California, while chartered in 1868 by the state Legislature, was mostly formed and fashioned as to its mission, structure and governance by the vision, fortitude and personality of four of its presidents – Daniel Coit Gilman (1872-1875); Benjamin Ide Wheeler (1899-1919); Robert Gordon Sproul (1930-1958); and Clark Kerr (1958-1967). -

A New Starr in Berkeley's Firmament

— Not for citation without permission — A New Starr in Berkeley’s Firmament: The Dedication of the C. V. Starr East Asian Library and the Chang-Lin Tien Center for East Asian Studies Opening of the C. V. Starr East Asian Library University of California, Berkeley October 17, 2007 Berkeley, California Pauline Yu President, American Council of Learned Societies As you may know, I received my doctorate—a few years ago, now—from Stanford University, fierce rival of Berkeley at Big Game every fall. And I spent almost 10 years as dean at the University of California, Los Angeles, which has chafed at being considered this campus’s ”Southern Branch” since its founding in 1919. So why am I here? There are extremely compelling reasons for me to resist participating in the dedication of yet another splendid building on this already impossibly beautiful campus with every fiber of my being. And yet, to the contrary, I am both pleased and honored to take part in this morning’s program along with my distinguished colleagues. We’re here, after all, to celebrate something whose significance transcends even the noblest of petty rivalries, a true milestone in the academic world: the construction of the first freestanding East Asian library in North America. It will also house the Chang-Lin Tien Center for East Asian Studies, named for Chancellor Tien, who was so devoted to his engineering lab he often made it—and not his home—his first stop after returning to Berkeley from a trip. This morning we inaugurate a great laboratory for the humanities and social sciences.