The Olive Family in Cultivation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

What Is a Tree in the Mediterranean Basin Hotspot? a Critical Analysis

Médail et al. Forest Ecosystems (2019) 6:17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-019-0170-6 RESEARCH Open Access What is a tree in the Mediterranean Basin hotspot? A critical analysis Frédéric Médail1* , Anne-Christine Monnet1, Daniel Pavon1, Toni Nikolic2, Panayotis Dimopoulos3, Gianluigi Bacchetta4, Juan Arroyo5, Zoltán Barina6, Marwan Cheikh Albassatneh7, Gianniantonio Domina8, Bruno Fady9, Vlado Matevski10, Stephen Mifsud11 and Agathe Leriche1 Abstract Background: Tree species represent 20% of the vascular plant species worldwide and they play a crucial role in the global functioning of the biosphere. The Mediterranean Basin is one of the 36 world biodiversity hotspots, and it is estimated that forests covered 82% of the landscape before the first human impacts, thousands of years ago. However, the spatial distribution of the Mediterranean biodiversity is still imperfectly known, and a focus on tree species constitutes a key issue for understanding forest functioning and develop conservation strategies. Methods: We provide the first comprehensive checklist of all native tree taxa (species and subspecies) present in the Mediterranean-European region (from Portugal to Cyprus). We identified some cases of woody species difficult to categorize as trees that we further called “cryptic trees”. We collected the occurrences of tree taxa by “administrative regions”, i.e. country or large island, and by biogeographical provinces. We studied the species-area relationship, and evaluated the conservation issues for threatened taxa following IUCN criteria. Results: We identified 245 tree taxa that included 210 species and 35 subspecies, belonging to 33 families and 64 genera. It included 46 endemic tree taxa (30 species and 16 subspecies), mainly distributed within a single biogeographical unit. -

Olea Europaea L. a Botanical Contribution to Culture

American-Eurasian J. Agric. & Environ. Sci., 2 (4): 382-387, 2007 ISSN 1818-6769 © IDOSI Publications, 2007 Olea europaea L. A Botanical Contribution to Culture Sophia Rhizopoulou National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Department of Biology, Section of Botany, Panepistimioupoli, Athens 157 84, Greece Abstract: One of the oldest known cultivated plant species is Olea europaea L., the olive tree. The wild olive tree is an evergreen, long-lived species, wide-spread as a native plant in the Mediterranean province. This sacred tree of the goddess Athena is intimately linked with the civilizations which developed around the shores of the Mediterranean and makes a starting point for mythological and symbolic forms, as well as for tradition, cultivation, diet, health and culture. In modern times, the olive has spread widely over the world. Key words: Olea • etymology • origin • cultivation • culture INTRODUCTION Table 1: Classification of Olea ewopaea Superdivi&on Speimatophyta-seed plants Olea europaea L. (Fig. 1 & Table 1) belongs to a Division Magnohophyta-flowenng plants genus of about 20-25 species in the family Oleaceae [1-3] Class Magn olio psi da- dicotyledons and it is one of the earliest cultivated plants. The olive Subclass Astendae- tree is an evergreen, slow-growing species, tolerant to Order Scrophulanale- drought stress and extremely long-lived, with a life Family Oleaceae- olive family expectancy of about 500 years. It is indicative that Genus Olea- olive Species Olea europaea L. -olive Theophrastus, 24 centuries ago, wrote: 'Perhaps we may say that the longest-lived tree is that which in all ways, is able to persist, as does the olive by its trunk, by its power of developing sidegrowth and by the fact its roots are so hard to destroy' [4, book IV. -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database. -

Winter Blooming Shrubs by RICHARD E

Winter Blooming Shrubs by RICHARD E. WEAVER, JR. Winters in the eastern part of this country south of Washington, D.C. are seldom as unpleasant as they are here in the Northeast. Of course the temperatures there are less extreme, but for those of us who appreciate plants and flowers, the real difference is perhaps due to the Camellias. Blooming through the worst weather that January and February have to offer, these wonderful plants with their bright and showy blooms make winter something almost worth anticipating. Although there are some hopeful new developments through con- centrated breeding efforts, we in most of the Northeast still must do without Camellias in our gardens. Nevertheless, there are a sur- prising number of hardy shrubs, perhaps less showy but still charm- ing and attractive, that will bloom for us through the winter and the early days of spring. Some, such as the Witch Hazels, are foolproof; others present a challenge for they are susceptible to our capricious winters and may lose their opening flowers to a cold March. For those gardeners willing to take the chance, a few of the best early- flowering shrubs displayed in the border, or as the focal point in a winter garden, will help to soften the harshness of the season. Many plants that bloom in the early spring have their flowers per- fectly formed by the previous fall. Certain of these do not require a period of cold dormancy, and in mild climates will flower intermit- tently during the fall and winter. Most species, however, do require an environmental stimulus, usually a period of cold temperatures, before the buds will break and the flowers open. -

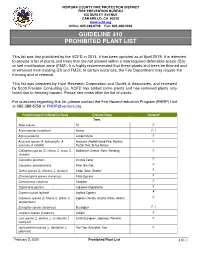

Guideline 410 Prohibited Plant List

VENTURA COUNTY FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT FIRE PREVENTION BUREAU 165 DURLEY AVENUE CAMARILLO, CA 93010 www.vcfd.org Office: 805-389-9738 Fax: 805-388-4356 GUIDELINE 410 PROHIBITED PLANT LIST This list was first published by the VCFD in 2014. It has been updated as of April 2019. It is intended to provide a list of plants and trees that are not allowed within a new required defensible space (DS) or fuel modification zone (FMZ). It is highly recommended that these plants and trees be thinned and or removed from existing DS and FMZs. In certain instances, the Fire Department may require the thinning and or removal. This list was prepared by Hunt Research Corporation and Dudek & Associates, and reviewed by Scott Franklin Consulting Co, VCFD has added some plants and has removed plants only listed due to freezing hazard. Please see notes after the list of plants. For questions regarding this list, please contact the Fire Hazard reduction Program (FHRP) Unit at 085-389-9759 or [email protected] Prohibited plant list:Botanical Name Common Name Comment* Trees Abies species Fir F Acacia species (numerous) Acacia F, I Agonis juniperina Juniper Myrtle F Araucaria species (A. heterophylla, A. Araucaria (Norfolk Island Pine, Monkey F araucana, A. bidwillii) Puzzle Tree, Bunya Bunya) Callistemon species (C. citrinus, C. rosea, C. Bottlebrush (Lemon, Rose, Weeping) F viminalis) Calocedrus decurrens Incense Cedar F Casuarina cunninghamiana River She-Oak F Cedrus species (C. atlantica, C. deodara) Cedar (Atlas, Deodar) F Chamaecyparis species (numerous) False Cypress F Cinnamomum camphora Camphor F Cryptomeria japonica Japanese Cryptomeria F Cupressocyparis leylandii Leyland Cypress F Cupressus species (C. -

Towards Resolving Lamiales Relationships

Schäferhoff et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2010, 10:352 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/10/352 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Towards resolving Lamiales relationships: insights from rapidly evolving chloroplast sequences Bastian Schäferhoff1*, Andreas Fleischmann2, Eberhard Fischer3, Dirk C Albach4, Thomas Borsch5, Günther Heubl2, Kai F Müller1 Abstract Background: In the large angiosperm order Lamiales, a diverse array of highly specialized life strategies such as carnivory, parasitism, epiphytism, and desiccation tolerance occur, and some lineages possess drastically accelerated DNA substitutional rates or miniaturized genomes. However, understanding the evolution of these phenomena in the order, and clarifying borders of and relationships among lamialean families, has been hindered by largely unresolved trees in the past. Results: Our analysis of the rapidly evolving trnK/matK, trnL-F and rps16 chloroplast regions enabled us to infer more precise phylogenetic hypotheses for the Lamiales. Relationships among the nine first-branching families in the Lamiales tree are now resolved with very strong support. Subsequent to Plocospermataceae, a clade consisting of Carlemanniaceae plus Oleaceae branches, followed by Tetrachondraceae and a newly inferred clade composed of Gesneriaceae plus Calceolariaceae, which is also supported by morphological characters. Plantaginaceae (incl. Gratioleae) and Scrophulariaceae are well separated in the backbone grade; Lamiaceae and Verbenaceae appear in distant clades, while the recently described Linderniaceae are confirmed to be monophyletic and in an isolated position. Conclusions: Confidence about deep nodes of the Lamiales tree is an important step towards understanding the evolutionary diversification of a major clade of flowering plants. The degree of resolution obtained here now provides a first opportunity to discuss the evolution of morphological and biochemical traits in Lamiales. -

Review on Production Techniques of GI Crop, Udupi Mallige

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2018; SP3: 50-52 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 National conference on “Conservation, Cultivation and JPP 2018; SP3: 50-52 Utilization of medicinal and Aromatic plants" HS Chaitanya (College of Horticulture, Mudigere Karnataka, 2018) Scientist (Horticulture), Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Brahmavar, Udupi District. Karnataka, India Review on production techniques of GI Crop, Udupi Nataraja S Mallige (Jasminum sambac (L.) Aiton) Associate Professor, Dept. of Botany, Sayadhri Science College, Shivamogga District, Karnataka, India HS Chaitanya, Nataraja S, Vikram HC and Jayalakshmi Narayan Hegde Vikram HC Abstract Assistant Professor (Contract), Jasmine, Jasminum sambac (L.) Aiton cv. Udupi Mallige belonging to family Oleaceae, is a fragrant ZAHRS, Brahmavara, Udupi commercial flower crop of coastal Karnataka. Udupi Mallige is being cultivated in homestead gardens District, Karnataka, India and is concentrated in the surrounding villages of Shanakarpura, in Udupi district. The crop has been tagged under Geographical Indication (GI) due to its unique fragrance and quality flowers from Udupi Jayalakshmi Narayan Hegde region. Udupi Mallige is extensively used in religious functions and perfumery industry as it is having Associate Professor, College of Agriculture, University of mild fragrance, which gives a feeling of optimism, euphoria and confidence. Its fragrance is also known Agricultural and Horticultural to cure depression, nervous exhaustion and stress. Udupi Mallige which has been recognised Sciences, Shivamogga, internationally for its fragrance has got potential demand for export market, especially to Gulf countries. Karnataka, India The crop flowers thought the year and the peak flowering is observed during March-April (on season). There is a demand for Udupi Mallige flowers during October to February (off season), as most of the religious functions and marriage ceremonies tend to occur during off season. -

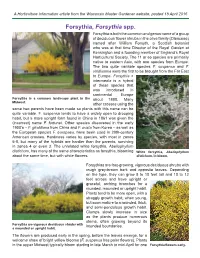

Forsythia.Pdf

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 18 April 2016 Forsythia, Forsythia spp. Forsythia is both the common and genus name of a group of deciduous fl ower shrubs in the olive family (Oleaceae) named after William Forsyth, a Scottish botanist who was at that time Director of the Royal Garden at Kensington and a founding member of England’s Royal Horticultural Society. The 11 or so species are primarily native to eastern Asia, with one species from Europe. The two quite variable species F. suspensa and F. viridissima were the fi rst to be brought from the Far East to Europe. Forsythia × intermedia is a hybrid of these species that was introduced in continental Europe Forsythia is a common landscape plant in the about 1880. Many Midwest. other crosses using the same two parents have been made so plants with this name can be quite variable. F. suspensa tends to have a widely open to drooping habit, but a more upright form found in China in 1861 was given the (incorrect) name F. fortunei. Other species discovered in the early 1900’s – F. giraldiana from China and F. ovata from Korea – as well as the European species F. europaea, have been used in 20th-century American crosses. Hardiness varies by species, with most in zones 5-8, but many of the hybrids are hardier than the parents, surviving in zones 4 or even 3. The unrelated white forsythia, Abeliophyllum distichum, has many of the same characteristics as forsythia, blooming White forsythia, Abeliophyllum about the same time, but with white fl owers. -

Plant List by Hardiness Zones

Plant List by Hardiness Zones Zone 1 Zone 6 Below -45.6 C -10 to 0 F Below -50 F -23.3 to -17.8 C Betula glandulosa (dwarf birch) Buxus sempervirens (common boxwood) Empetrum nigrum (black crowberry) Carya illinoinensis 'Major' (pecan cultivar - fruits in zone 6) Populus tremuloides (quaking aspen) Cedrus atlantica (Atlas cedar) Potentilla pensylvanica (Pennsylvania cinquefoil) Cercis chinensis (Chinese redbud) Rhododendron lapponicum (Lapland rhododendron) Chamaecyparis lawsoniana (Lawson cypress - zone 6b) Salix reticulata (netleaf willow) Cytisus ×praecox (Warminster broom) Hedera helix (English ivy) Zone 2 Ilex opaca (American holly) -50 to -40 F Ligustrum ovalifolium (California privet) -45.6 to -40 C Nandina domestica (heavenly bamboo) Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (bearberry - zone 2b) Prunus laurocerasus (cherry-laurel) Betula papyrifera (paper birch) Sequoiadendron giganteum (giant sequoia) Cornus canadensis (bunchberry) Taxus baccata (English yew) Dasiphora fruticosa (shrubby cinquefoil) Elaeagnus commutata (silverberry) Zone 7 Larix laricina (eastern larch) 0 to 10 F C Pinus mugo (mugo pine) -17.8 to -12.3 C Ulmus americana (American elm) Acer macrophyllum (bigleaf maple) Viburnum opulus var. americanum (American cranberry-bush) Araucaria araucana (monkey puzzle - zone 7b) Berberis darwinii (Darwin's barberry) Zone 3 Camellia sasanqua (sasanqua camellia) -40 to -30 F Cedrus deodara (deodar cedar) -40 to -34.5 C Cistus laurifolius (laurel rockrose) Acer saccharum (sugar maple) Cunninghamia lanceolata (cunninghamia) Betula pendula -

Hypericaceae) Heritiana S

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 5-19-2017 Systematics, Biogeography, and Species Delimitation of the Malagasy Psorospermum (Hypericaceae) Heritiana S. Ranarivelo University of Missouri-St.Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Ranarivelo, Heritiana S., "Systematics, Biogeography, and Species Delimitation of the Malagasy Psorospermum (Hypericaceae)" (2017). Dissertations. 690. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/690 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Systematics, Biogeography, and Species Delimitation of the Malagasy Psorospermum (Hypericaceae) Heritiana S. Ranarivelo MS, Biology, San Francisco State University, 2010 A Dissertation Submitted to The Graduate School at the University of Missouri-St. Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Biology with an emphasis in Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics August 2017 Advisory Committee Peter F. Stevens, Ph.D. Chairperson Peter C. Hoch, Ph.D. Elizabeth A. Kellogg, PhD Brad R. Ruhfel, PhD Copyright, Heritiana S. Ranarivelo, 2017 1 ABSTRACT Psorospermum belongs to the tribe Vismieae (Hypericaceae). Morphologically, Psorospermum is very similar to Harungana, which also belongs to Vismieae along with another genus, Vismia. Interestingly, Harungana occurs in both Madagascar and mainland Africa, as does Psorospermum; Vismia occurs in both Africa and the New World. However, the phylogeny of the tribe and the relationship between the three genera are uncertain. -

New Records of Alien Species in the Ohio Vascular Flora1

New Records of Alien Species in the Ohio Vascular Flora1 MICHAEL A. VINCENT AND ALLISON W. CUSICK, Department of Botany, Miami University, Oxford, OH 45056, and Division of Natural Areas and Preserves, Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Fountain Square, Columbus, OH 43224 ABSTRACT. Examination of specimens of vascular plants from various herbaria, as well as field collections, have revealed 70 taxa not previously reported for Ohio, or previously reported without documentation. This paper documents these new taxa, 44% of which are escapes of woody landscape plants. The specimens cited represent 55 genera in 30 families. Of these, the following genera are first reports for the state: Achyranthes, Albizia, Carthamus, Cercidiphyllum, Cotoneaster, Dactyloctenium, Fontanesia, Gaillardia, Guizotia, Gypsophila, Stenosiphon, Tripsacum, and Zinnia. Cercidiphyllaceae is the only family reported as new for the state. Some taxa cited in this paper represent first reports as escapes for North America. These are Cotoneaster divaricatus (Rosaceae), Fontanesia fortunei (Oleaceae), Magnolia X soulangeana (Magnoliaceae), Magnolia stellata (Magnoliaceae), Viburnum buddleifolium (Capri- foliaceae), and Viburnum x rhytidiphylloides (Caprifoliaceae). OHIO J SCI 98 (2): 10-17, 1998 INTRODUCTION these proved to be new to the state. Specimens were The alien element in the Ohio vascular flora is dynamic. also examined at the following herbaria: BAYLU, BHO, Taxa appear, flourish, and, occasionally, disappear on BGSU, CINC, CLM, CM, DAO, F, GA, GB, GH, ISC, KE, waves of disturbance. Agriculture, transportation, urbani- MICH, MO, MU, NA, NLU, NY, OS, OSH, UAM, UC, US, zation and a host of anthropogenic factors constantly VDB, and VPI (herbarium acronyms from Holmgren and alter habitats and introduce novelties into our flora.