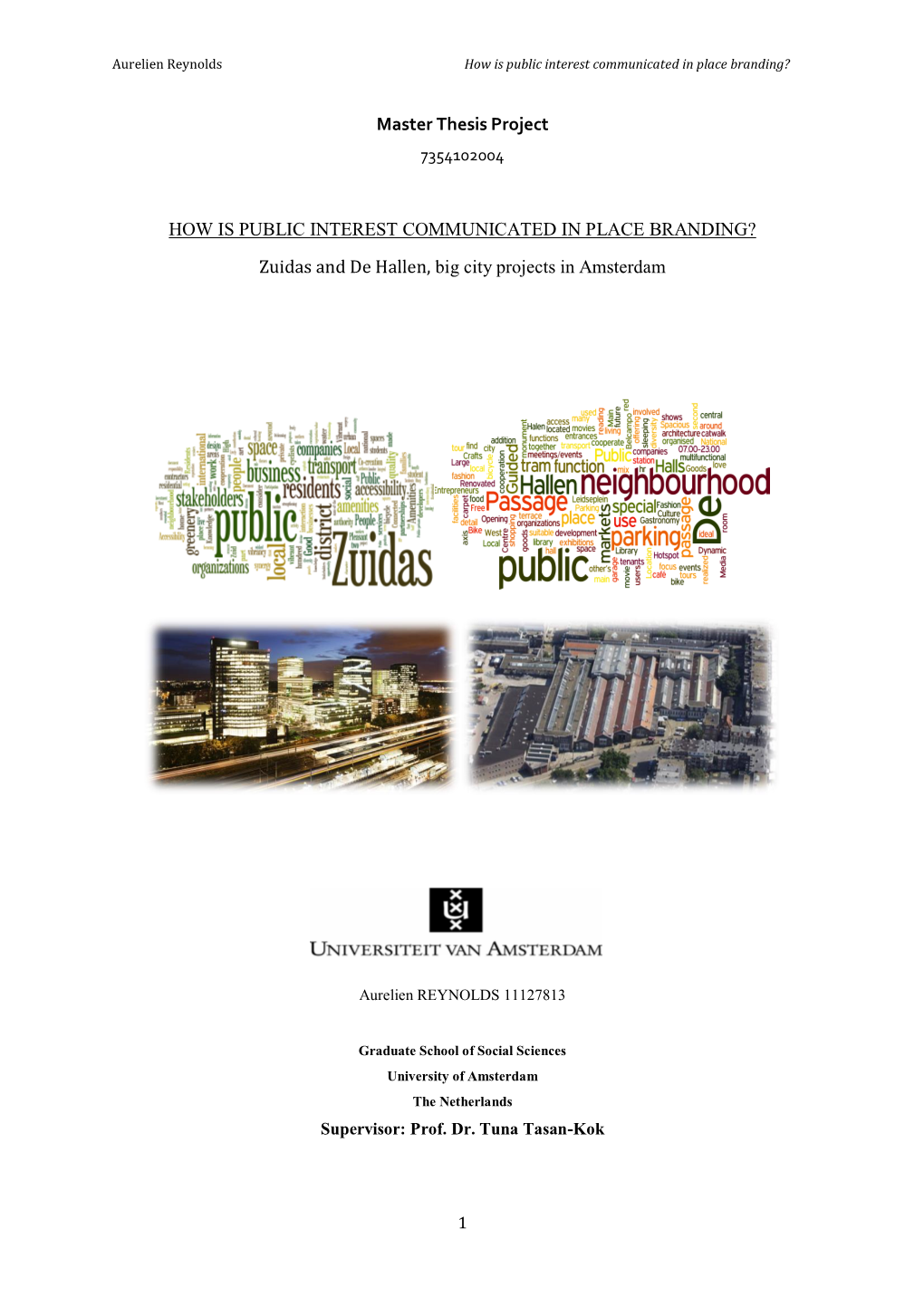

De Hallen and Zuidas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highrise – Lowland

ctbuh.org/papers Title: Highrise – Lowland Author: Pi de Bruijn, Partner, de Architekten Cie Subjects: Building Case Study Urban Design Keywords: Urban Habitat Verticality Publication Date: 2004 Original Publication: CTBUH 2004 Seoul Conference Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Pi de Bruijn Highrise – Lowland Pi de Bruijn Ir, Master of Architecture Partner in de Architekten Cie, Amsterdam, Netherlands Abstract High-rise in the Netherlands, lowland par excellence, could there be a greater contrast? In a country dominated by water and often by low roofs of cloud, high-rise construction is almost by definition a Statement. Perhaps this is the reason why it has been such a controversial topic for so long, with supporters and opponents assailing one another with contrasting ideas on urban development and urbanism. Particularly in historical settings, these ‘new icons’ were long regarded as an erosion of our historical legacy, as big- business megalomania. Such a style does not harmonize with this cosy, homely country, it was maintained, with its consultative structures and penchant for regulation. Moreover, high-rise construction hardly ever took place anyway because there were infinitely more opportunities for opponents to apply delaying tactics than there were for proponents to deploy means of acceleration, and postponement soon meant abandonment. Nevertheless, a turning point now seems to have been reached. Everyone is falling over one another to allow architectonic climaxes determine the new urban identity. Could it be more inconsistent? In order to discover the origins of the almost emotional resistance to high-rise construction and why attitudes have changed, we shall first examine the physical conditions and the socio-economic context of the Netherlands. -

4B Bijlage Bij Beantwoording V

Lijst Buurtstraatquotes, inclusief gegevens individuele grondquotes buurtstraatquote per buurtstraat voor meergezinswoningen en voor eengezinswoningen, inclusief minimum, maximum en standaard deviatie van de individuele grondquotes onder embargo tot 8 mei 2017 Lijst Buurtstraatquotes, inclusief gegevens individuele grondquotes Toelichting Deze lijst bevat de buurstraatquotes inclusief gegevens over de achterliggende individuele grondquotes. De buurtstraatquote wordt berekend door individuele grondquotes van eengezins- of meergezinswoningen in een buurtstraat te middelen. De lijst geeft de minimale, maximale en de standaarde deviatie van de individuele grondquotes in een buurtstraat. De individuele grondquotes in een buurstraat hebben niet altijd een directe relatie met de buurtstraatquote. De buurstraatquote kan gebasseerd zijn op de buurtquote en de buurstraatquote kan afgetopt zijn op 49%. Daarnaast kan de buurstraatquote begrensd zijn op de bandbreedte van 5% boven of onder de buurtquote. Indien dit het geval is, is dit aangegeven in de lijst. Indien een buurtstraat of buurt te weinig eengezins- of meergezinswoningen bevat waarvoor een individuele grondquote is berekend, kan voor de betreffende buurstraat geen buurstraatquote worden bepaald. De lijst bevat daarom buurstraten die geen buurstraatquote hebben voor eengezins-, meergezinswoningen of voor beide. In deze gevallen wordt de buurstraatquote op basis van maatwerk bepaald. 2 van 107 Lijst Buurtstraatquotes, inclusief gegevens individuele grondquotes Meergezinswoningen Eengezinswoningen -

Leefbaarheid En Veiligheid De Leefbaarheid En Veiligheid Van De Woonomgeving Heeft Invloed Op Hoe Amsterdammers Zich Voelen in De Stad

13 Leefbaarheid en veiligheid De leefbaarheid en veiligheid van de woonomgeving heeft invloed op hoe Amsterdammers zich voelen in de stad. De mate waarin buurtgenoten met elkaar contact hebben en de manier waarop zij met elkaar omgaan zijn daarbij van belang. Dit hoofdstuk gaat over de leefbaar- heid, sociale cohesie en veiligheid in de stad. Auteurs: Hester Booi, Laura de Graaff, Anne Huijzer, Sara de Wilde, Harry Smeets, Nathalie Bosman & Laurie Dalmaijer 150 De Staat van de Stad Amsterdam X Kernpunten Leefbaarheid op te laten groeien. Dat is het laagste Veiligheid ■ De waardering voor de eigen buurt cijfer van de Metropoolregio Amster- ■ Volgens de veiligheidsindex is Amster- is stabiel en goed. Gemiddeld geven dam. dam veiliger geworden sinds 2014. Amsterdammers een 7,5 als rapport- ■ De tevredenheid met het aanbod aan ■ Burgwallen-Nieuwe Zijde en Burgwal- cijfer voor tevredenheid met de buurt. winkels voor dagelijkse boodschap- len-Oude Zijde zijn de meest onveilige ■ In Centrum neemt de tevredenheid pen in de buurt is toegenomen en buurten volgens de veiligheidsindex. met de buurt af. Rond een kwart krijgt gemiddeld een 7,6 in de stad. ■ Er zijn minder misdrijven gepleegd in van de bewoners van Centrum vindt Alleen in Centrum is men hier minder Amsterdam (ruim 80.000 bij de politie dat de buurt in het afgelopen jaar is tevreden over geworden. geregistreerde misdrijven in 2018, achteruitgegaan. ■ In de afgelopen tien jaar hebben –15% t.o.v. 2015). Het aantal over- ■ Amsterdammers zijn door de jaren steeds meer Amsterdammers zich vallen neemt wel toe. heen positiever geworden over het ingezet voor een onderwerp dat ■ Slachtofferschap van vandalisme komt uiterlijk van hun buurt. -

Baetostraat 21-II Te Amsterdam

Baetostraat 21-II te Amsterdam Vraagprijs € 239.000,- k.k. Amsterdam Baetostraat 21-II Vraagprijs: € 239.000,-- k.k. Aanvaarding: in overleg Thuis in de regio Lichte en goed onderhouden driekamerhoekwoning van ca. 55m², met twee slaapkamers, balkon en twee eigen bergingen op de zolderetage! Door de hoekligging hebben alle ruimten voldoende ramen en is het huis als zeer licht te omschrijven! Omgeving: Deze woning is gelegen in stadsdeel West in Bos & Lommer. Deze wijk heeft vele voorzieningen. Voor uw dagelijkse boodschappen kunt u terecht in de Jan van Galenstraat of de Bos en Lommerweg en Bos en Lommerplein, beide korte loopafstand. Het Bos en Lommerplein beschikt over een gezellige markt. Ook de karakteristieke wijk de Jordaan met haar gezellige terrasjes en winkels is nabij, net als de Kinkerbuurt (De Hallen) en de Overtoom. De Dam bereikt u binnen 8 minuten fietsen en het Centraal Station kost u slechts 10 minuten. Qua uitvalswegen zijn de A4 en A10 zeer nabij en is er een goed openbaar vervoer- netwerk (diverse tram- en busverbindingen). Recreatie is mogelijk in het Erasmuspark, Westerpark en Rembrandtpark (op loopafstand). Mocht u meer behoefte hebben aan de natuur, dan fietst u in 10 minuten naar het veelzijdige recreatiegebied Spaarn- woude. Sportgelegenheden zijn te vinden in het nabij gelegen Sportcomplex Mercator, met fitnesscen- trum, groot zwembad en sauna & solarium faciliteiten. Voor een leuke voorstelling in de buurt kan je te- recht bij Podium Mozaïek. Daar worden allerlei voorstellingen georganiseerd op het gebied van dans, theater en muziek. Daarnaast zijn er in deze buurt vele gezellige restaurantjes te vinden. -

Buitenveldert

Een veranderende tuinstad: Buitenveldert Auteur: Kimberley van Gent Begeleider: Stefan Metaal Datum : 20 juni 2016 Studentnummer 10451277 0 Opleiding: Planologie Inhoudsopgave 1. Inleiding ....................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Probleemstelling ........................................................................................................................ 3 2. Theoretisch kader ........................................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Veranderende wijken .......................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Verandering in de Westelijke tuinsteden ............................................................................ 5 2.3 Buitenveldert ....................................................................................................................... 6 2.4 Toestroom jonge mensen .................................................................................................... 7 2.5 Publieke familiariteit ........................................................................................................... 8 3. Methodologische verantwoording ............................................................................................ 10 3.1 Locaties .............................................................................................................................. 10 3.2 Selectie -

Meldpunt Overlastschiphol

MELDPUNT OVERLAST SCHIPHOL HET CONTRAST TUSSEN PAPIER EN WERKELIJKHEID EEN ONDERZOEK VAN SP AMSTERDAM DECEMBER 2018 Inhoud Inleiding 3 Meer dan een kwart van de Amsterdammers die overlast ervaren woont buiten de geluidszone 4 Verschillende soorten van overlast 4 De overlast op stadsdeelniveau Centrum 6 Noord 8 Oost 10 Zuid 11 West 15 Nieuw-West 17 Zuidoost 20 Conclusie 21 Aanbeveling 23 Bronvermelding 24 Bijlage 1: Voorbeelden van meldingen 25 Bijlage 2: Kaart van de geluidszone 30 2 Inleiding De geluidszone: ‘een papieren werkelijkheid’ Na een uitspraak van de Inspectie voor de Leefomgeving en Transport werd in juli 2018 duidelijk dat niet iedere klacht over Schiphol in behandeling wordt genomen. Wie wil dat zijn of haar klacht wordt meegenomen in de rapportages moet aan twee voorwaarden voldoen. De indiener van een klacht moet in een gemeente wonen die zitting heeft in de Omgevingsraad van Schiphol en de indiener moet binnen de zogeheten ‘geluidszone’ wonen in de directe omgeving van Schiphol. Voor Amsterdam betekent dit in de praktijk dat Amsterdammers uit stadsdeel centrum niet mogen klagen over geluidsoverlast. Ook grote delen van de stadsdelen West, Noord, Oost en Zuidoost vallen buiten de denkbeeldige geluidszone. Alleen stadsdeel Nieuw-West valt in zijn geheel binnen de geluidszone.1 De voorwaarde dat men binnen de gestelde geluidszone moet wonen heeft tot gevolg dat er dagelijks honderden vliegtuigen over een buurt kunnen vliegen, maar een melding van eventuele overlast niet in behandeling zal worden genomen. Anders gezegd: de geluidszone creëert een papieren werkelijkheid die geen recht doet aan de overlast die Amsterdammers ervaren. Wanneer we een blik op de kaart werpen, wordt duidelijk hoe absurd het markeren van een geluidszone op buurtniveau kan uitpakken. -

Overamstelstraat 101 1091 TM AMSTERDAM

Overamstelstraat 101 1091 TM AMSTERDAM VRAAGPRIJS: € 289.000,- KOSTEN KOPER Burger Elkerbout Makelaars en Taxateurs o.z. B.V. Blasiusstraat 66 hs | 1091 CV Amsterdam | t 020 622 21 99 [email protected] | www.burgerelkerbout.nl Vrijblijvende verkoopinformatie Een goed ingedeeld en heerlijk licht 3-kamerappartement van circa 80 m² gelegen op de tweede verdieping met een ruim balkon aan de voorzijde op het zuidoosten. Het appartementencomplex uit 1992 ligt in de populaire Weesperzijdebuurt, nabij de Weesperzijde en de Amstel. Een aantrekkelijke woonomgeving op steenworp afstand van de binnenstad en de Pijp. Alle denkbare voorzieningen liggen in de buurt. Zeer goed bereikbaar met de auto en het openbaar vervoer. Indeling Via de gemeenschappelijke entree gaat u naar de tweede verdieping. Entree, ruime hal met toegang tot alle vertrekken. De ruime woonkamer met open keuken (alleen de aansluitingen zijn aanwezig) ligt aan de voorzijde en geeft toegang tot het zonnige balkon (1,70 diep). De twee slaapkamers liggen aan de achterzijde en geven vrij uitzicht op de gemeenschappelijke binnentuin. De vernieuwde badkamer is voorzien van een douche, wastafel en wasmachineaansluiting. Er is een separaat toilet met fonteintje. Ruime inpandige berging en een bergkast met de CV-ketel en watermeter. De woning heeft betonnen vloeren en dubbele (isolerende) beglazing. Aan de straatzijde is een fietsenberging (6.00 x 2,92 meter) die gedeeld wordt met zes andere woningen. Algemeen Bouwjaar 1992 en gesplitst in appartementsrechten in 2003 Woonoppervlakte Circa 80 m² (gemeten volgens de NEN-2580) Inhoud Circa 216 m³ Oplevering In overleg, kan per direct Eigen grond/erfpacht Erfpachtgrond van de gemeente Amsterdam, de canon is afgekocht tot en met 15 januari 2044, Algemene Bepalingen 2000. -

Ideaalstad Buitenveldert

Ideaalstad Buitenveldert (verslag Harry Gosen) Van Eesterengesprek 16 februari 2011 Inleiding Arjan Hebly1 Aan de hand van een kaart over de stedenbouwkundige structuur en architectuur uit 2008 n.a.v. het 50 jarige bestaan van buitenveldert. Wat kengetallen per 2008 11.250 woningen 2 19.020 inwoners3 11.000 huishoudens 60% éénpersoons huishoudens 16% huishiudens met kinderen 1.6 personen per huishouden 21 % van de bevolking is Westerse Allochtoon 4 16% niet Westerse Allochtoon Inwonertal gaat de laatste jaren heel langzaam omhoog . Vernieuwing buitenveldert gaat gelijkmatig. Het is absoluut geen probleemwijk. 1 Hebly Theunissen Architecten, Oude Delft 145, 2611 HA DELFT,telefoon: 015 - 2 123 857, e-mail: [email protected] 2 In Stadsdeel Nieuw-West 2010, 60114 woningen (bron: Kerncijfers Amsterdam 2010, OenS) 3 In Stadsdeel Nieuw-west 2010, 135188 inwoners. 4 In Stadsdeel Nieuw-West 2010: 11,2 % Westerse Allochtonen, 49,1 % niet Westerse Allochtonen. 1 Bekend Buitenveldert (wat beelden) Vrije Universiteit Buitenveldert stond in het collectieve geheugen bekend om de woning van Joop den Uyl 5aan het Weldam 5 (bron: Google) of het lied “zondagmiddag Buitenveldert” van Frans Halsema. 5 Zie voor informatie over Joop den Uyl in Buitenveldert o.a. Bleich A.. Joop den Uyl 1919-1987, Dromer en Doorbouwer, Amsterdam, 2008. 2 De Zuid-as (Ing hoofkantoor) Kalfjeslaan Huis van Cornelis van Eesteren Weldam 11, ontwerper van het Algemeen Uitbreidingsplan. 3 Floriade terrein (1972) nu Amstelpark. Waarom een onderzoek over Buitenveldert? Niet alleen geïntereseerd in het ontwerp, maar ook in het verhaal er achter, de ideeën , de totstandkoming, de uitwerking. De architectuur en de stedenbouw van Buitenveldert is momenteel nog grotendeels intact. -

Competitie-Indeling (Veldvoetbal) District: KNVB-DISTRICT-WEST1 Comp.Jaar: 2012

Printdatum: 16-jul-2012 Competitie-indeling (veldvoetbal) District: KNVB-DISTRICT-WEST1 Comp.jaar: 2012 0531 0531 B-Junioren Zondag (A-cat) Hoofdklasse C 1 Buitenboys B1 10:15 2 Dijk De B1 11:30 3 Ouderkerk B1 12:00 4 Purmersteijn B1 10:00 5 AFC B1 14:45 6 AS 80 B1 11:30 7 Buitenveldert B1 12:15 8 Weesp FC B1 11:30 9 DSS B1 13:00 10 Always Forward B1 12:00 11 DWV B1 11:30 12 IVV B1 12:00 1e klasse 05 1 DIOS B1 11:00 2 DCG B1 12:30 3 GeuzenM'meer B1 10:00 4 VVA/Spartaan B1 11:30 5 Nieuw Sloten sv B1 11:00 6 Sporting Krommenie B1 14:00 7 OSV B1 11:30 8 Purmerend B1 11:30 9 Blauw Wit Amsterdam B1 12:00 10 Zeeburgia B1 11:00 11 EVC B1 13:00 12 Vitesse 22 B1 11:00 1e klasse 06 1 RKDES B1 14:00 2 TABA B1 12:15 3 Overbos B1 14:30 4 Sporting Almere B1 10:00 5 RAP B1 12:00 6 Pancratius B1 11:00 7 Buitenboys B2 12:45 8 Sporting Martinus B1 11:30 9 Abcoude B1 12:00 10 AFC B2 14:45 11 Zwanenburg B1 11:00 12 RODA 23 B1 12:00 1 Printdatum: 16-jul-2012 Competitie-indeling (veldvoetbal) District: KNVB-DISTRICT-WEST1 Comp.jaar: 2012 0532 0532 B-Junioren Zondag (najaar) 2e klasse 01 Always Forward B2 09:30 Andijk B1 11:00 Dynamo B1 13:30 Grasshoppers B1 14:00 Hollandia T B1 11:00 Medemblik B1 14:00 Spartanen B1 14:00 Spirit'30 B1 10:00 Succes B1 14:00 Valken De B1 11:00 VVS 46 B1 10:00 VVW B1 11:00 2e klasse 02 AFC 34 B1 12:00 Always Forward B3 09:30 Beemster B1 11:00 IVV B2 10:00 Limmen B1 12:00 Monnickendam B1 12:45 Purmerland B1 12:00 Rijp (de) B1 14:00 RKEDO B1 11:45 Vitesse 22 B2 14:00 Volendam (rkav) B1 12:00 Wherevogels De B1 11:00 2e klasse 03 DSOV B1 11:00 DSS B2 11:00 HYS B1 10:30 KFC B1 09:30 Kon. -

Cultuurhistorische Verkenning En Advies Buitenveldert 04-–

April 2012 Cultuurhistorische verkenning en advies Buitenveldert Amsterdam 2012 April 2012 Gemeente Amsterdam Bureau Monumenten & Archeologie Inhoud Inleiding 3 1 Beleidskader 4 2 Historisch stedenbouwkundige analyse 5 2.1 Voorgeschiedenis 5 2.2 Uitbreiding in de Binnendijksche Buitenveldertsche Polder 5 2.3 Infrastructuur 10 2.4 Primaire groenstructuur 10 2.5 Bebouwing 10 2.6 Gedeeltelijke decentralisatie 11 3 Typering buurten 12 Beantwoording vragen Stadsdeel Zuid 16 2 April 2012 Gemeente Amsterdam Bureau Monumenten & Archeologie Inleiding Stadsdeel Zuid heeft, in het kader van de herziening van het bestemmingsplan Buitenveldert, BMA gevraagd om te adviseren over de cultuurhistorische waarden die bij het opstellen van een bestemmingsplan van belang zijn. Dit heeft geresulteerd in een uiteenzetting van de ontstaansgeschiedenis en een typering van de verschillende buurten binnen het gebied. Naast deze uiteenzetting van algemene aard heeft BMA op verzoek van het stadsdeel in het advies een aantal specifieke kwesties behandeld, op basis van de voorlopige waarderingskaart. Het betreft de volgende vragen: - Geef een uitsplitsing in de waardering van bebouwing: 1. welke bebouwing mag absoluut niet gesloopt worden (monumentwaardig en een belangrijke bijdrage aan het tuinstedelijk ensemble); 2. welke bebouwing zou eventueel gesloopt kunnen worden, mits deze op dezelfde locatie wordt teruggebouwd (niet monumentwaardig maar wel belangrijk voor AUP); 3. welke bebouwing bezit architectonisch geringe waarde en levert geen belangrijke bijdrage aan de stedenbouwkundige opzet van Buitenveldert. 4. Geef een waardering van het gebruik van de plinten van grondgebonden woningen (waar kan een ander functie en vormgeving ervoor zorgen dat de monumentwaardigheid dan wel bijdrage aan het AUP schade wordt toegebracht) 5. Geef een waardering van de aanwezigheid van garageboxen voor de stedenbouwkundige opzet van Buitenveldert 6. -

Migration of the Four Largest Cities in the Netherlands

Statistics Netherlands Department of population PO Box 4000 2270 JM Voorburg The Netherlands Migration of the four largest cities in the Netherlands Mila van Huis, Han Nicolaas, Michel Croes Abstract The proportion of people who move to, from or within large cities in the Netherlands is much bigger than the corresponding figure for other municipalities. In 1997 a total number of 153 removals per thousand of the inhabitants took place in the four largest cities in the Netherlands. This is considerably higher than the corresponding mobility for the Netherlands as a whole (111). Big city mobility concerns mostly migration within the cities. Since the introduction of a new system of decentralised automated population registers in 1994, Statistics Netherlands obtains complete and timely information on this intra city migration. This paper discusses the migration flows in 1997 to, from and within the capital city of the Netherlands, Amsterdam. The results will be compared to the migration flows of Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht, the other three big cities of the Netherlands. For these big cities net migration with regard to the other municipalities in the Netherlands was negative, net international migration was positive. Attention was paid to the migration flows to and from the various city wards. Wards with highest mobility are generally situated centrally in town and have a high proportion of foreigners and young inhabitants. Most wards at the edge of town attract inhabitants from the municipality itself. Mobility from these wards to one of the municipalities in the urban agglomeration is high. 1. Introduction In recent years the four big cities in the Netherlands (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht) received considerable attention. -

Little Tokyo in Suburban Amsterdam an Analysis on Residential Clustering of Japanese Migrants in Amstelveen

UNIVERSITY OF AMSTERDAM Little Tokyo in suburban Amsterdam An analysis on residential clustering of Japanese migrants in Amstelveen Vincent Buurma 10752951 1/15/2018 Little Tokyo in Suburban Amsterdam An analysis on residential clustering of Japanese migrants in Amstelveen Vincent Buurma 10752951 Bachelor thesis Course code: 734301500Y Bachelor Human Geography and Urban Planning (Sociale Geografie en Planologie) College Social Sciences University of Amsterdam Assignment date: January 15th, 2018 Supervisor & second reader: Dr. Dennis Arnold & Dhr. M.A. Verzijl, MSc. Words: 17.500 1 Preface This thesis marks the end of my bachelor’s degree in Human Geography & Urban Planning at the University of Amsterdam. The conducted research involves multiple fields of study; Geography, Sociology, Anthropology, Economics and Urban Planning. It is therefore very representative for the bachelor. The multidisciplinary character of Human Geography & Urban Planning has always been one of the things I enjoyed most of this major. Because multiple interesting fields of study are combined within one. My interest for Japan started in my exchange semester in Asia, when I also visited Japan. Japan is in my opinion one of the most fascinating and mysterious countries in the world. I find it therefore very interesting that so many Japanese people live in the town I grew up in, Amstelveen. In my personal opinion are Amstelveen and Tokyo or Osaka two worlds apart. Perhaps Japanese people view this differently. Or perhaps there are other reasons why they live in Amstelveen. This will all be discussed in this thesis. I want to thank my supervisor Dennis Arnold for his guidance during the past five months.