The Grief Bearers a Thesis Submitted to Kent State University in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY TO LOOT TO HEW & EDEN by EMILY KRUSE CARR A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA JUly2010 © EMILY KRUSE CARR 2010 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-69475-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-69475-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduce, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

ABSTRACT WHAT IF YOU're LONELY: JESSICA STORIES By

ABSTRACT WHAT IF YOU’RE LONELY: JESSICA STORIES by Michael Stoneberg This novel-in-stories follows Jessica through the difficulties of her early twenties to her mid- thirties. During this period of her life she struggles with loneliness and depression, attempting to find some form of meaningful connection through digital technologies as much as face-to-face interaction, coming to grips with a non-normative sexuality, finding and losing her first love and dealing with the resultant constant pull of this person on her psyche, and finally trying to find who in fact she, Jessica, really is, what version of herself is at her core. The picture of her early adulthood is drawn impressionistically, through various modes and styles of narration and points of view, as well as through found texts, focusing on preludes and aftermaths and asking the reader to intuit and imagine the spaces between. WHAT IF YOU’RE LONELY: JESSICA STORIES A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Michael Stoneberg Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2014 Advisor______________________ Margaret Luongo Reader_______________________ Joseph Bates Reader_______________________ Madelyn Detloff TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Revision Page 1 2. Invoice for Therapy Services Page 11 3. Craigslist Page 12 4. Some Things that Make Us—Us Page 21 5. RE: Recent Account Activity Page 30 6. Sirens Page 31 7. Hand-Gun Page 44 8. Hugh Speaks Page 48 9. “The Depressed Person” Page 52 10. Happy Hour: Last Day/First Day Page 58 11. -

Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas. Lise Brandt Pedersen Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pedersen, Lise Brandt, "Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2159. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2159 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I 72- 17,797 PEDERSEN, Lise Brandt, 1926- SHAVIAN .SHAKESPEARE:' SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, XEROXA Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan tT,TITn ^TnoT.r.a.A'TTAItf U4C PPPM MT PROPTT.MF'n FVAOTT.V AR RECEI VE D SHAVIAN SHAKESPEARE: SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Lise Brandt Pedersen B.A., Tulane University, 1952 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1963 December, 1971 ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to thank Dr. -

PWTORCH NEWSLETTER • PAGE 2 Www

ISSUE #1255 - MAY 26, 2012 TOP FIVE STORIES OF THE WEEK PPV ROUNDTABLE (1) Raw expanding to three hours on July 23 (2) Impact going live every week this summer (3) Flair parting ways with TNA, WWE bound WWE OVER THE LIMIT (4) Raw going “interactive” with weekly voting Staff Scores & Reviews (5) Laurinaitis pins Cena after Show turns heel Pat McNeill, columnist (6.5): The main problem with WWE Over The Limit? The main event went over the limit of what we’ll accept from WWE. You can argue that there was no reason to book John Cena against John Laurinaitis on a pay-per-view, and you’d be right. RawHEA eDLxINpE AaNnALYdSsIS to thrhoeurse, a nhd uosuaullyr tsher e’Js eunoulgyh re2de3eming But on top of that, there was no reason to book content to make it worth the investment. But Cena versus Laurinaitis to go as long as any other three hours? Three hours of lousy content is By Wade Keller, editor major pay-per-view match. And there was no enough that next time viewers might just tune in reason for Cena to drag the match out. It didn’t fit If you follow an industry long enough, you’re for a just an hour instead of the usual two and the storyline. And it made John Cena look like a bound to see some bad decisions being made. certainly not commit to all three. Or they might chump. or like The Stinger, when Big Show turned Some are worse than others, but it’s rare when pick their segments, watching the predictably heel for the umpteenth time and cost him the you think you might be seeing the Worst newsmaking segments at the start of each hour match. -

Central Skagit Rural Partial County Library District Regular Board Meeting Agenda April 15, 2021 7:00 P.M

DocuSign Envelope ID: 533650C8-034C-420C-9465-10DDB23A06F3 Central Skagit Rural Partial County Library District Regular Board Meeting Agenda April 15, 2021 7:00 p.m. Via Zoom Meeting Platform 1. Call to Order 2. Public Comment 3. Approval of Agenda 4. Consent Agenda Items Approval of March 18, 2021 Regular Meeting Minutes Approval of March 2021 Payroll in the amount of $38,975.80 Approval of March 2021 Vouchers in the amount of $76,398.04 Treasury Reports for March 2021 Balance Sheet for March 2021 (if available) Deletion List – 5116 Items 5. Conflict of Interest 5. Communications 6. Director’s Report 7. Unfinished Business A. Library Opening Update B. Art Policy (N or D) 8. New Business A. Meeting Room Policy (N) B. Election of Officers 9. Other Business 10. Adjournment There may be an Executive Session at any time during the meeting or following the regular meeting. DocuSign Envelope ID: 533650C8-034C-420C-9465-10DDB23A06F3 Legend: E = Explore Topic N = Narrow Options D = Decision Information = Informational items and updates on projects Parking Lot = Items tabled for a later discussion Current Parking Lot Items: 1. Grand Opening Trustee Lead 2. New Library Public Use Room Naming Jeanne Williams is inviting you to a scheduled Zoom meeting. Topic: Board Meeting Time: Mar 18, 2021 07:00 PM Pacific Time (US and Canada) Every month on the Third Thu, until Jan 20, 2022, 11 occurrence(s) Mar 18, 2021 07:00 PM Apr 15, 2021 07:00 PM May 20, 2021 07:00 PM Jun 17, 2021 07:00 PM Jul 15, 2021 07:00 PM Aug 19, 2021 07:00 PM Sep 16, 2021 07:00 PM Oct 21, 2021 07:00 PM Nov 18, 2021 07:00 PM Dec 16, 2021 07:00 PM Jan 20, 2022 07:00 PM Please download and import the following iCalendar (.ics) files to your calendar system. -

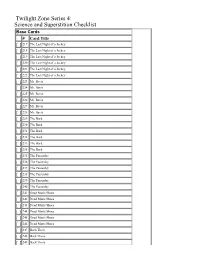

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred -

State of the (Student) Union Address

12 smallTALK w March 7, 2011 Volume 50, Issue 10 TNA Q & A with ONARCH iMPACT President COREBOARD hits Hancock M Fayetteville ...page 3 S ...page 6 GAME RESULTS small ALK Baseball March 7, 2011 The sTudenT voice of MeThodisT universiTy Methodist University Date Opponent Result Volume 50, Issue 10 Fayetteville, NC 2/23 Hampden-Sydney College W 7-4 T 2/26 LaGrange College W 8-1 www.sMallTalkMu.coM 2/27 LaGrange College W 8-3 3/1 Immaculata University W 14-1 3/2 Lynchburg College W 12-0 Softball Date Opponent Result State of the (Student) Union Address 2/25 Piedmont College L 1-3 2/25 Lynchburg College L 4-7 2/26 Salisbury University L 2-9 President Hancock answers students’ questions at Town Hall Meeting 2/26 Eastern Mennonite University W 2-0 2/27 Roanoke College L 1-13, L 5-13 of a university,” Hancock said to the crowd. “I think I have the best job in America, and I Men’s Tennis want each and every one of you to feel like you are at the best school in America.” Date Opponent Result “I’ve been waiting 27 years for Dr. Hendricks to retire,” joked Hancock. “And now, 2/23 Barton College L 4-5 just a little older than 52, I am here doing exactly what I set my sight on so long ago.” 2/26 Benedict College W 9-0 Hancock explained to the crowd that he would attempt to answer every question to the 2/26 Guilford College W 8-1 3/3 Mount Olive College L 1-8 best of his ability, but asked students to be patient with him if he did not know the answer and promised that he would do his best to answer questions as he learned more about Women’s Tennis Methodist University. -

Ecological Consequences Artificial Night Lighting

Rich Longcore ECOLOGY Advance praise for Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting E c Ecological Consequences “As a kid, I spent many a night under streetlamps looking for toads and bugs, or o l simply watching the bats. The two dozen experts who wrote this text still do. This o of isis aa definitive,definitive, readable,readable, comprehensivecomprehensive reviewreview ofof howhow artificialartificial nightnight lightinglighting affectsaffects g animals and plants. The reader learns about possible and definite effects of i animals and plants. The reader learns about possible and definite effects of c Artificial Night Lighting photopollution, illustrated with important examples of how to mitigate these effects a on species ranging from sea turtles to moths. Each section is introduced by a l delightful vignette that sends you rushing back to your own nighttime adventures, C be they chasing fireflies or grabbing frogs.” o n —JOHN M. MARZLUFF,, DenmanDenman ProfessorProfessor ofof SustainableSustainable ResourceResource Sciences,Sciences, s College of Forest Resources, University of Washington e q “This book is that rare phenomenon, one that provides us with a unique, relevant, and u seminal contribution to our knowledge, examining the physiological, behavioral, e n reproductive, community,community, and other ecological effectseffects of light pollution. It will c enhance our ability to mitigate this ominous envirenvironmentalonmental alteration thrthroughough mormoree e conscious and effective design of the built environment.” -

![ONE NIGHT @ the CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset By: Arun K Gupta]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7467/one-night-the-call-center-chetan-bhagat-typeset-by-arun-k-gupta-1187467.webp)

ONE NIGHT @ the CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset By: Arun K Gupta]

ONE NIGHT @ THE CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset by: Arun K Gupta] This is someway my story. A great fun, inspirational One! Before you begin this book, I have a small request. Right here, note down three things. Write down something that i) you fear, ii) makes you angry and iii) you don’t like about yourself. Be honest, and write something that is meaningful to you. Do not think too much about why I am asking you to do this. Just do it. One thing I fear: __________________________________ One thing that makes me angry: __________________________________ One thing I do not like about myself: __________________________________ Okay, now forget about this exercise and enjoy the story. Have you done it? If not, please do. It will enrich your experience of reading this book. If yes, thanks Sorry for doubting you. Please forget about the exercise, my doubting you and enjoy the story. PROLOGUE _____________ The night train ride from Kanpur to Delhi was the most memorable journey of my life. For one, it gave me my second book. And two, it is not every day you sit in an empty compartment and a young, pretty girl walks in. Yes, you see it in the movies, you hear about it from friend’s friend but it never happens to you. When I was younger, I used to look at the reservation chart stuck outside my train bogie to check out all the female passengers near my seat (F-17 to F-25)is what I’d look for most). Yet, it never happened. -

Fade In: Int. Art Gallery – Day

FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY Exhibition Guide FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY March 03 – May 08, 2016 Works by Danai Anesiadou, Nairy Baghramian, Michael Bell-Smith, Dora Budor, Heman Chong, Mike Cooter, Brice Dellsperger, GALA Committee, Mathis Gasser, Jamian Juliano-Villani, Bertrand Lavier, William Leavitt, Christian Marclay, Rodrigo Matheus, Allan McCollum, Henrique Medina, Carissa Rodriguez, Cindy Sherman, Amie Siegel, Scott Stark, and Albert Whitlock; performances and public programs by Casey Jane Ellison, Mario García Torres, Alex Israel, Thirteen Black Cats, and more. Recasting the gallery as a set for dramatic scenes, FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY explores the role that art plays in narrative film and television. FADE IN features the work of 25 artists and considers a history of art as seen in classic movies, soap operas, science fiction, pornography and musicals. These works have been sourced, reproduced and created in response to artworks that have been made to appear on-screen, whether as props, set dressings, plot devices, or character cues. The nature of the exhibition is such that sculptures, paintings and installations transition from prop to image to art object, staging an enquiry into whether these fictional depictions in mass media ultimately have greater influence in defining a collective understanding of art than art itself does. Certain preoccupations with artworks are established early on in cinematic history: the preciousness of art objects anchors their roles as plot drivers, and anxieties intensify regarding the vitality of artworks and their perceived abilities to wield power over viewers or to capture spirits. Such themes were famously explored in the 1945 film adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, from which Cindy Sherman has sourced the original portrait painted for the production. -

November 23, 2015 Wrestling Observer Newsletter

1RYHPEHU:UHVWOLQJ2EVHUYHU1HZVOHWWHU+ROPGHIHDWV5RXVH\1LFN%RFNZLQNHOSDVVHVDZD\PRUH_:UHVWOLQJ2EVHUYHU)LJXUH)RXU2« RADIO ARCHIVE NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE THE BOARD NEWS NOVEMBER 23, 2015 WRESTLING OBSERVER NEWSLETTER: HOLM DEFEATS ROUSEY, NICK BOCKWINKEL PASSES AWAY, MORE BY OBSERVER STAFF | [email protected] | @WONF4W TWITTER FACEBOOK GOOGLE+ Wrestling Observer Newsletter PO Box 1228, Campbell, CA 95009-1228 ISSN10839593 November 23, 2015 UFC 193 PPV POLL RESULTS Thumbs up 149 (78.0%) Thumbs down 7 (03.7%) In the middle 35 (18.3%) BEST MATCH POLL Holly Holm vs. Ronda Rousey 131 Robert Whittaker vs. Urijah Hall 26 Jake Matthews vs. Akbarh Arreola 11 WORST MATCH POLL Jared Rosholt vs. Stefan Struve 137 Based on phone calls and e-mail to the Observer as of Tuesday, 11/17. The myth of the unbeatable fighter is just that, a myth. In what will go down as the single most memorable UFC fight in history, Ronda Rousey was not only defeated, but systematically destroyed by a fighter and a coaching staff that had spent years preparing for that night. On 2/28, Holly Holm and Ronda Rousey were the two co-headliners on a show at the Staples Center in Los Angeles. The idea was that Holm, a former world boxing champion, would impressively knock out Raquel Pennington, a .500 level fighter who was known for exchanging blows and not taking her down. Rousey was there to face Cat Zingano, a fight that was supposed to be the hardest one of her career. Holm looked unimpressive, barely squeaking by in a split decision. Rousey beat Zingano with an armbar in 14 seconds. -

Hard Justice Free

FREE HARD JUSTICE PDF Lori Foster | 384 pages | 21 Mar 2017 | Harlequin Books | 9780373799329 | English | United States Hard Justice | Halo Machinima | Fandom Its promotional trailer was released Hard Justice YouTube on September 20, Hard Justice Bernard Brown is the starring character, an ex-cop Hard Justice resigns from the Hard Justice department of Regent City after deciding Hard Justice doesn't want to be a part of or contribute to the fact that Regent City is slowly becoming a fascist police state. Unfortunately for him, Esoteria is not much of a difference. After Hard Justice to get a Hard Justice, Bernard finds a job at E. Despite having a dark theme, Hard Justice still contains plenty Hard Justice DigitalPh33r's trademark humor. Max tells Eddie to steel himself for the coming task. Eddie decides to open the door, but Max tells him "Don't split hairs with me. Why go around something when you can go through it", and blasts open the door with his rocket launcher. Entering the house, Max discovers that the occupant of the house has downloaded three tracks of music, causing Eddie to puke violently. Just then, the occupant of the Hard Justice returns, and he is placed under arrest by Max, who tells him that downloading three tracks is equivalent to killing three Hard Justice. Eddie then fires at the "offender", who flees. Max blows up his car. After failing to catch him, they taser him twice and restrain him. In the Hard Justice, Bernard arrives at Esoteria airport, and after clearing the numerous security checkpoints, getting stopped at each of them Hard Justice being nervous.