Class, Race, Credibility, and Authenticity Within the Hip-Hop Music Genre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papeete, Tahiti

Global Aviation M A G A Z I N E Issue 69/ May 2016 Page 1 - Introduction Welcome on board this Global Aircraft. In this issue of the Global Aviation Magazine, we will take a look at two more Global Lines cities Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada and Papeete, Tahiti. We also take another look at a featured aircraft in the Global Fleet. This month’s featured aircraft is the Embraer ERJ-145. We wish you a pleasant flight. 2. Vancouver, B.C., Canada – West Meets Best 4. Papeete, Tahiti – Pacific Paradise 6. Pilot Information 8. Introducing the Embraer ERJ-145LR – With All the Frills 10. In-flight Movies/Featured Music Page 2 – Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada – West Meets Best Vancouver is a coastal city located in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, Canada. It is named for British Captain George Vancouver, who explored and first mapped the area in the 1790s. The metropolitan area is the most populous in Western Canada and the third-largest in the country, with the city proper ranked eighth among Canadian cities. According to the 2006 census Vancouver had a population of 578,041 and just over 2.1 million people resided in its metropolitan area. Over the last 30 years, immigration has dramatically increased, making the city more ethnically and linguistically diverse; 52% do not speak English as their first language. Almost 30% of the city's inhabitants are of Chinese heritage. From a logging sawmill established in 1867 a settlement named Gastown grew, around which a town site named Granville arose. With the announcement that the railhead would reach the site, it was renamed "Vancouver" and incorporated as a city in 1886. -

Is Hip Hop Dead?

IS HIP HOP DEAD? IS HIP HOP DEAD? THE PAST,PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF AMERICA’S MOST WANTED MUSIC Mickey Hess Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hess, Mickey, 1975- Is hip hop dead? : the past, present, and future of America’s most wanted music / Mickey Hess. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 (alk. paper) 1. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3531H47 2007 782.421649—dc22 2007020658 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007020658 ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 ISBN-10: 0-275-99461-9 First published in 2007 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION 1 1THE RAP CAREER 13 2THE RAP LIFE 43 3THE RAP PERSONA 69 4SAMPLING AND STEALING 89 5WHITE RAPPERS 109 6HIP HOP,WHITENESS, AND PARODY 135 CONCLUSION 159 NOTES 167 BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 INDEX 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of a Rider University Summer Fellowship helped me com- plete this book. I want to thank my colleagues in the Rider University English Department for their support of my work. -

7Th Heaven Is an Experience You Just Have to See and Hear! 7Th Heaven Has Charted #1 on the Midwest Billboard Charts Three Times in the Past Three Years

BIO 2021 7th heaven is an experience you just have to see and hear! 7th heaven has charted #1 on the Midwest Billboard Charts three times in the past three years. The band has been heard on over 7 radio stations in Chicagoland with their hits “Beautiful Life”, “This Is Where The Party’s At”, Stoplight”, "Better This Way" and "Sing". Also known for the famous "30 Songs in 30 Minutes" medley of songs from the 70's and 80's, 7th heaven has been an entertainment staple for 36 years. Playing around 200 shows a year, with an average of 100 outdoor events, 7th heaven has earned the right to say ..."We've seen a million faces and rocked them all!" • Three # 1 Hit Songs on the Billboard Charts - “Stoplight”, “Sing” & “Better This Way” • Six Major Radio Hit Songs -"This Is Where The Party's At", "Time Of Our Lives", "Beautiful Life", “Stoplight”, "Better This Way" and "Sing" • Five CD’s reached #1 on the Billboard Charts • 7th heaven’s original songs are played on many major radio stations • Opened for “Bon Jovi” & “Kid Rock” at Solider Field to 80,000 people • Opened for “Styx” to 80,000 people at a sold-out show • Written/Recorded over 5,000 songs to date • Released “Jukebox”, a collection of 700 original songs • Seen on NBC, ABC, FOX & WGN • "Beautiful Life" heard on the MTV show "Teen Mom 2" Episode 11 - Trouble in Paradise • "She Could Use a Little Sunshine" used in Ziplock TV Commercial • Started in 1985 - 34 years ago (when we were little kids) • Recognized as one of the biggest independent bands in the world • Wrote & Performed TV/Radio Commercial for “Empress Casino” • Wrote & Performed TV Commercial for “Walter E. -

Elvis Presley Music

Vogue Madonna Take on Me a-ha Africa Toto Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) Eurythmics You Make My Dreams Daryl Hall and John Oates Taited Love Soft Cell Don't You (Forget About Me) Simple Minds Heaven Is a Place on Earth Belinda Carlisle I'm Still Standing Elton John Wake Me Up Before You Go-GoWham! Blue Monday New Order Superstition Stevie Wonder Move On Up Curtis Mayfield For Once In My Life Stevie Wonder Red Red Wine UB40 Send Me On My Way Rusted Root Hungry Eyes Eric Carmen Good Vibrations The Beach Boys MMMBop Hanson Boom, Boom, Boom!! Vengaboys Relight My Fire Take That, LuLu Picture Of You Boyzone Pray Take That Shoop Salt-N-Pepa Doo Wop (That Thing) Ms Lauryn Hill One Week Barenaked Ladies In the Summertime Shaggy, Payvon Bills, Bills, Bills Destiny's Child Miami Will Smith Gonna Make You Sweat (Everbody Dance Now) C & C Music Factory Return of the Mack Mark Morrison Proud Heather Small Ironic Alanis Morissette Don't You Want Me The Human League Just Cant Get Enough Depeche Mode The Safety Dance Men Without Hats Eye of the Tiger Survivor Like a Prayer Madonna Rocket Man Elton John My Generation The Who A Little Less Conversation Elvis Presley ABC The Jackson 5 Lessons In Love Level 42 In the Air Tonight Phil Collins September Earth, Wind & Fire In Your Eyes Kylie Minogue I Want You Back The Jackson 5 Jump (For My Love) The Pointer Sisters Rock the Boat Hues Corportation Jolene Dolly Parton Never Too Much Luther Vandross Kiss Prince Karma Chameleon Culture Club Blame It On the Boogie The Jacksons Everywhere Fleetwood Mac Beat It -

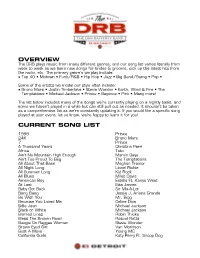

DRB Master Song List.Pages

OVERVIEW The DRB plays music from many different genres, and our song list varies literally from week to week as we learn new songs for brides & grooms, pick up the latest hits from the radio, etc. The primary genre’s we play include: • Top 40 • Motown • Funk/R&B • Hip Hop • Jazz • Big Band/Swing • Pop • Some of the artists we model our style after include: • Bruno Mars • Justin Timberlake • Stevie Wonder • Earth, Wind & Fire • The Temptations • Michael Jackson • Prince • Beyonce • Pink • Many more! The list below includes many of the songs we’re currently playing on a nightly basis, and some we haven’t played in a while but can still pull out as needed. It shouldn’t be taken as a comprehensive list as we’re constantly updating it. If you would like a specific song played at your event, let us know, we’re happy to learn it for you! CURRENT SONG LIST 1999 Prince 24K Bruno Mars 7 Prince A Thousand Years Christina Perri Africa Toto Ain’t No Mountain High Enough Marvin Gaye Ain’t Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Summer Long Kid Rock All Blues Miles Davis American Boy Estelle Ft. Kanye West At Last Etta James Baby Got Back Sir Mix-A-Lot Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande Be With You Mr. Bigg Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Billie Jean Michael Jackson Black or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Bless The Broken Road Rascal Flatts Boogie On Reggae Woman Stevie Wonder Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Bust A Move Young MC California Gurls Katy Perry Ft. -

Friday Essay: Clueless at 25—Like, a Totally Important Teen Film

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Macrossan, Phoebe & Ford, Jessica (2020) Friday Essay: Clueless at 25 - like, a totally important teen film. The Conversation, 17 July 2020. [Featured article] This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/202965/ c Consult author(s) regarding copyright matters This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] License: Creative Commons: Attribution-No Derivative Works 4.0 Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https:// theconversation.com/ friday-essay-clueless-at-25-like-a-totally-important-teen-film-140749 Friday Essay: Clueless at 25 — like, a totally important teen film 17/7/2020 Phoebe Macrossan, Jessica Ford While many teen films fade away never to be heard of again, Clueless, a loose adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma, has remained in the cultural consciousness since its 1995 release. -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

Vanilla Ice Hard to Swallow Video

Vanilla ice hard to swallow video click here to download Hard to Swallow is the third studio album by American rapper Vanilla Ice. Released by Republic Records in , the album was the first album the performer. Vanilla Ice - Hard to Swallow - www.doorway.ru Music. Stream Hard To Swallow by Vanilla Ice and tens of millions of other songs on all . Related Video Shorts. Discover releases, reviews, credits, songs, and more about Vanilla Ice - Hard To Swallow at Discogs. Complete your Vanilla Ice collection. Find a Vanilla Ice - Hard To Swallow first pressing or reissue. Complete your Vanilla Ice collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Listen free to Vanilla Ice – Hard To Swallow (Living, Scars and more). 13 tracks ( ). Discover more music, concerts, videos, and pictures with the largest. Play video. REX/Shutterstock. Vanilla Ice, “Too Cold”. Vanilla Ice guilelessly claimed his realness from the beginning, even as his image In , he tried to hop aboard the rap-rock train with Hard to Swallow, an album that. Now there's a setup for a new joke: Vanilla Ice, the tormented rocker. As a pre- emptive strike, his new album is called ''Hard to Swallow''. Hard to Swallow, an Album by Vanilla Ice. Released 28 October on Republic (catalog no. UND; CD). Genres: Nu Metal, Rap Rock. Featured. Shop Vanilla Ice's Hard to swallow CD x 2 for sale by estacio at € on CDandLP - Ref Vanilla Ice Hard To Swallow; Video. €. Add to cart. List of the best Vanilla Ice songs, ranked by fans like you. This list includes 20 3 . -

Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 12-14-2020 Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music Cervanté Pope Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Pope, Cervanté, "Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music" (2020). University Honors Theses. Paper 957. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.980 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music By Cervanté Pope Student ID #: 947767021 Portland State University Pope 2 Introduction In mass communication, gatekeeping refers to how information is edited, shaped and controlled in efforts to construct a “social reality” (Shoemaker, Eichholz, Kim, & Wrigley, 2001). Gatekeeping has expanded into other fields throughout the years, with its concepts growing more and more easily applicable in many other aspects of life. One way it presents itself is in regard to racial inclusion and equality, and despite the headway we’ve seemingly made as a society, we are still lightyears away from where we need to be. Because of this, the concept of cultural property has become even more paramount, as a means for keeping one’s cultural history and identity preserved. -

Language Contact and US-Latin Hip Hop on Youtube

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research York College 2019 Choutouts: Language Contact and US-Latin Hip Hop on YouTube Matt Garley CUNY York College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/yc_pubs/251 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Choutouts: Language contact and US-Latin hip hop on YouTube Matt Garley This paper presents a corpus-sociolinguistic analysis of lyrics and com- ments from videos for four US-Latinx hip hop songs on YouTube. A ‘post-varieties’ (Seargeant and Tagg 2011) analysis of the diversity and hybridity of linguistic production in the YouTube comments finds the notions of codemeshing and plurilingualism (Canagarajah 2009) useful in characterizing the language practices of the Chicanx community of the Southwestern US, while a focus on the linguistic practices of com- menters on Northeastern ‘core’ artists’ tracks validate the use of named language varieties in examining language attitudes and ideologies as they emerge in commenters’ discussions. Finally, this article advances the sociolinguistics of orthography (Sebba 2007) by examining the social meanings of a vast array of creative and novel orthographic forms, which often blur the supposed lines between language varieties. Keywords: Latinx, hip hop, orthography, codemeshing, language contact, language attitudes, language ideologies, computer-mediated discourse. Choutouts: contacto lingüístico y el hip hop latinx-estadounidense en YouTube. Este estudio presenta un análisis sociolingüístico de letras de canciones y comentarios de cuatro videos de hip hop latinx-esta- dounidenses en YouTube. -

Rcc the CCCCCD Brown Comes Back Strong, House of Pain Needs to Come Again

FEATURES SEPTEMBER 16, 1992 ] rcc THE CCCCCD Brown comes back strong, House of Pain needs to come again By TJ Stancil Of course, this album was the album in “Something in proud of Cypress Hill’s assistance Music Editor probably made before someone Common.” The album has slow on their album. decided to remix those tracks so jams in abundance as well as the With a song like “Jump Yo, what’s up everybody? I can’t throw out blame. The typical B. Brown dance floor jam, Around,” it would be assumed that I’m back wilh another year of album as is is a Neo-Reggae but the slow jams sometimes seem this album isp^etty hype. WRONG! giving you insight on what’s hot classic (in my opinion) which hollow since he obviously doesn’t Let me tell you why it is definitely and what ’ s not in black and urban should be looked at. Other songs mean them (or does he?). not milk. contemporary music. This year, of mention are ‘Them no care,” Also, some of the slow jams, the First, all of their songs, like with a new staff and new format. “Nuff Man a Dead,” and “Oh majority of which were written and Cypress Hill’s, talk about smoking Black Ink will go further than It’s You.” Enjoy the return of produced by L.A. and Babyface, blounts and getting messed up. before in the realm of African- Reggae, but beware cheap seem as though they would sound Secondly, most of the beats sound American journalism. -

Mother-Women and the Construction of the Maternal Body in Harriet Jacobs, Kate Chopin, and Evelyn Scott

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2013 “Taming the Maternal”: Mother-women and the Construction of the Maternal Body in Harriet Jacobs, Kate Chopin, and Evelyn Scott Kelly Ann Masterson [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Masterson, Kelly Ann, "“Taming the Maternal”: Mother-women and the Construction of the Maternal Body in Harriet Jacobs, Kate Chopin, and Evelyn Scott. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1647 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Kelly Ann Masterson entitled "“Taming the Maternal”: Mother-women and the Construction of the Maternal Body in Harriet Jacobs, Kate Chopin, and Evelyn Scott." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Mary E. Papke, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Katherine L. Chiles, William J. Hardwig Accepted