Constituting Love in Persianate Cinemas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Digital Movies As Malaysian National Cinema A

Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Hsin-ning Chang April 2017 © 2017 Hsin-ning Chang. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema by HSIN-NING CHANG has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Erin Schlumpf Visiting Assistant Professor of Film Studies Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT CHANG, HSIN-NING, Ph.D., April 2017, Interdisciplinary Arts Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema Director of dissertation: Erin Schlumpf This dissertation argues that the alternative digital movies that emerged in the early 21st century Malaysia have become a part of the Malaysian national cinema. This group of movies includes independent feature-length films, documentaries, short and experimental films and videos. They closely engage with the unique conditions of Malaysia’s economic development, ethnic relationships, and cultural practices, which together comprise significant understandings of the nationhood of Malaysia. The analyses and discussions of the content and practices of these films allow us not only to recognize the economic, social, and historical circumstances of Malaysia, but we also find how these movies reread and rework the existed imagination of the nation, and then actively contribute in configuring the collective entity of Malaysia. 4 DEDICATION To parents, family, friends, and cats in my life 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Prof. -

Hubert Bals Fund

HUBERT BALS FUND COMPLETE RESULTS 1988-2016 • Script and Project Development support SELECTION 2016 • Post-production support Almost in Love Brzezicki, Leonardo (Argentina) • The Bridge Lotfy, Hala (Egypt) • Death Will Come and Will Have Your Eyes Torres Leiva, José Luis (Chile) • A Land Imagined Yeo Siew Hua (Singapore)• The Load Glavonic, Ognjen (Serbia) • Men in the Sun Fleifel, Mahdi (Greece) • Narges Rasoulof, Mohammad (Iran) • Octopus Skin Barragán, Ana Cristina (Ecuador) • The Orphanage Sadat, Shahrbanoo (Afghanistan) • The Reports on Sarah and Saleem Alayan, Muayad (Palestine) • Trenque Lauquen Citarella, Laura (Argentina) • White Widow Hermanus, Oliver (South Africa) • The Load, Glavonic, Ognjen (Serbia) During the NATO bombing of Serbia in 1999, Vlada is driving a freezer truck across the country. He does not want to know what the load is, but his cargo slowly becomes his burden. • Script and Project Development support SELECTION 2015 • Post-production support Alba Barragan, Ana Cristina (Ecuador) 2016 • Antigone González-Rubio, Pedro (Mexico) • Arnold Is a Model Student Prapapan, Sorayos (Thailand) • Barzagh Ismailova, Saodat (Uzbekistan) • Beauty and the Dogs Ben Hania, Kaouther (Tunisia) • Brief Story from the Green Planet Loza, Santiago (Argentina) • Burning Birds Pushpakumara, Sanjeewa (Sri Lanka) 2016 • Era o Hotel Cambridge Caffé, Eliane (Brazil) 2016 • The Fever Da-Rin, Maya (Brazil) • La flor Llinás, Mariano (Argentina) 2016 • Hedi Ben Attia, Mohamed (Tunisia) 2016 • Kékszakállú Solnicki, Gastón (Argentina) 2016 • Killing -

Olive Films Presents

Mongrel Media Presents WHEN WE LEAVE A Film by Feo Aladag (118min., German, 2011) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html Cast Umay ….SIBEL KEKILLI Kader (Umay’s father) ….SETTAR TANRIÖGEN Halime (Umay’s mother) ….DERYA ALABORA Stipe (Umay’s colleague) ….FLORIAN LUKAS Mehmet(Umay’s older brother) ….TAMER YIGIT Acar (Umay’s younger brother) ….SERHAD CAN Rana (Umay’s younger sister) ….ALMILA BAGRIACIK Atife (Umay’s best friend) ….ALWARA HÖFELS Gül (Umay’s boss) ….NURSEL KÖSE Cem (Umay’s son) ….NIZAM SCHILLER Kemal (Umay’s husband) ….UFUK BAYRAKTAR Duran (Rana’s fiancé) ….MARLON PULAT Crew Script & Direction ….FEO ALADAG Producers ….FEO ALADAG, ZÜLI ALADAG Casting ….ULRIKE MÜLLER, HARIKA UYGUR, LUCY LENNOX Director of Photography ….JUDITH KAUFMANN Editor ….ANDREA MERTENS Production Design ….SILKE BUHR Costume Design ….GIOIA RASPÉ Sound ….JÖRG KIDROWSKI Score ….MAX RICHTER, STÉPHANE MOUCHA Make-up MONIKA MÜNNICH, MINA GHORAISHI Germany, 2010 Length: 119 minutes Format: CinemaScope 1:2.35 Sound system: Dolby Digital In German and in Turkish with English subtitles Synopsis What would you sacrifice for your family’s love? Your values? Your freedom? Your life? German-born Umay flees from her oppressive marriage in Istanbul, taking her young son Cem with her. She hopes to find a better life with her family in Berlin, but her unexpected arrival creates intense conflict. -

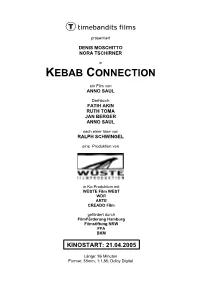

Kebab Connection

präsentiert DENIS MOSCHITTO NORA TSCHIRNER in KEBAB CONNECTION ein Film von ANNO SAUL Drehbuch FATIH AKIN RUTH TOMA JAN BERGER ANNO SAUL nach einer Idee von RALPH SCHWINGEL eine Produktion von in Ko-Produktion mit WÜSTE Film WEST WDR ARTE CREADO Film gefördert durch FilmFörderung Hamburg Filmstiftung NRW FFA BKM KINOSTART: 21.04.2005 Länge: 96 Minuten Format: 35mm, 1:1,85; Dolby Digital KEBAB CONNECTION VERLEIH timebandits films GmbH Stubenrauchstraße 2 14482 Potsdam Tel.: 0331 70 44 50 Fax.: 0331 70 44 529 [email protected] PRESSEBETREUUNG boxfish films Graf Rudolph Steiner GbR Senefelderstrasse 22 10437 Berlin Tel: 030 / 44044 751 Fax: 030 / 44044 691 E-mail: [email protected] Die offizielle Website des Films lautet: www.kebabconnection.de Weiteres Pressematerial steht online für Sie bereit unter: www.boxfish-films.de Seite 2 von 30 KEBAB CONNECTION INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Besetzung / Stab .......................................................................................4 Kurzinhalt / Pressenotiz.............................................................................5 Langinhalt..................................................................................................6 Produktionsnotizen ....................................................................................8 Interview mit Anno Saul.............................................................................11 Interview mit Nora Tschirner......................................................................14 Interview mit Denis Moschitto....................................................................16 -

Die Mechanik Der Erregung

Kultur SHOWGESCHÄFT Die Mechanik der Erregung Der inszenierte Wirbel um die Porno-Vergangenheit Sibel Kekillis, der deutschtürkischen Hauptdarstellerin im Berlinale-Siegerfilm „Gegen die Wand“, enthüllt vor allem eines: So freizügig sich eine Gesellschaft auch gibt – pseudoprüde Empörung zieht immer noch. KERSTIN STELTER / WÜSTE FILM / WÜSTE STELTER KERSTIN „Gegen die Wand“-Darsteller Ünel, Kekilli: Verschwitzte Enthüllungsarbeit nach dem Jubel über den Festivaltriumph uf der ersten Seite von „Bild“ bietet Hilfe an), tapfere Sibel (Wir sind stolz prangte am vergangenen Mittwoch auf sie) – das Blatt deklinierte den Fall nach AUschi Glas, 59, das sorgenfaltige allen Regeln des Boulevards durch. Reh. „Uschi Glas steht sündiger Film-Diva Dank der Enthüllung zog Kekilli, 23, in mutig bei“, lautete die Zeile. der Woche nach dem Triumph des „Gegen Heilige Uschi, da kam sie tatsächlich auf die Wand“-Melodrams bei der Berlinale- die Frontpage gewackelt, die Frau Sünde, Preisverleihung so viel Interesse auf sich, die „Bösartigkeit der menschlichen Natur“ dass der Regisseur des Films, der Ham- (Immanuel Kant). Ein anderes Wild, die burger Fatih Akin, neben der in Heilbronn rehäugige Sibel Kekilli, Hauptdarstellerin aufgewachsenen Jungschauspielerin nur des mit dem Goldenen Berlinale-Bären aus- noch eine Nebenrolle zu spielen schien. gezeichneten deutschen Films „Gegen die „Warum drehte die zarte Diva so harte Wand“, war auf dem Porno-Lotterlager er- Pornos?“, lautete die fürsorglich-kultur- wischt worden – „Bild“ fuhr seine neueste kritische Schlüsselfrage der „Bild“-Kam- Kampagne: Schlimme Sibel (Wie kann sie uns so täuschen), arme Sibel (Die Eltern „Bild“-Zeitung vom 17. Februar (Ausriss) verstoßen sie), hilfsbedürftige Sibel (Uschi Schlimme Sibel, arme Sibel 160 der spiegel 9/2004 pagne. -

South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation

The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation By Jisung Catherine Kim A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kristen Whissel, Chair Professor Mark Sandberg Professor Elaine Kim Fall 2013 The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation © 2013 by Jisung Catherine Kim Abstract The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation by Jisung Catherine Kim Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Kristen Whissel, Chair In The Intimacy of Distance, I reconceive the historical experience of capitalism’s globalization through the vantage point of South Korean cinema. According to world leaders’ discursive construction of South Korea, South Korea is a site of “progress” that proves the superiority of the free market capitalist system for “developing” the so-called “Third World.” Challenging this contention, my dissertation demonstrates how recent South Korean cinema made between 1998 and the first decade of the twenty-first century rearticulates South Korea as a site of economic disaster, ongoing historical trauma and what I call impassible “transmodernity” (compulsory capitalist restructuring alongside, and in conflict with, deep-seated tradition). Made during the first years after the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the films under consideration here visualize the various dystopian social and economic changes attendant upon epidemic capitalist restructuring: social alienation, familial fragmentation, and widening economic division. -

Dvd Digital Cinema System Systema Dvd Digital Cinema Sistema De Cinema De Dvd Digital Th-A9

DVD DIGITAL CINEMA SYSTEM SYSTEMA DVD DIGITAL CINEMA SISTEMA DE CINEMA DE DVD DIGITAL TH-A9 Consists of XV-THA9, SP-PWA9, SP-XCA9, and SP-XSA9 Consta de XV-THA9, SP-PWA9, SP-XCA9, y SP-XSA9 Consiste em XV-THA9, SP-PWA9, SP-XCA9, e SP-XSA9 STANDBY/ON TV/CATV/DBS AUDIO VCR AUX FM/AM DVD TITLE SUBTITLE DECODE AUDIO ZOOM DIGEST TIME DISPLAY RETURN ANGLE CHOICE SOUND CONTROL SUBWOOFER EFFECT VCR CENTER TEST TV REAR-L SLEEP REAR-R SETTING TV RETURN FM MODE 100+ AUDIO/ PLAY TV/VCR MODE CAT/DBS ENTER SP-XSA9 SP-XCA9 SP-XSA9 THEATER DSP POSITION MODE TV VOLCHANNEL VOLUME TV/VIDEO MUTING B.SEARCH F.SEARCH /REW PLAY FF DOWN TUNING UP REC STOP PAUSE MEMORY STROBE DVD MENU RM-STHA9U DVD CINEMA SYSTEM SP-PWA9 XV-THA9 INSTRUCTIONS For Customer Use: INSTRUCCIONES Enter below the Model No. and Serial No. which are located either on the rear, INSTRUÇÕES bottom or side of the cabinet. Retain this information for future reference. Model No. Serial No. LVT0562-010A [ UW ] Warnings, Cautions and Others Avisos, Precauciones y otras notas Advertêcias, precauções e outras notas Caution - button! CAUTION Disconnect the XV-THA9 and SP-PWA9 main plugs to To reduce the risk of electrical shocks, fire, etc.: shut the power off completely. The button on the 1. Do not remove screws, covers or cabinet. XV-THA9 in any position do not disconnect the mains 2. Do not expose this appliance to rain or moisture. line. The power can be remote controlled. -

The Black Gangster and the Latino Cleaning Lady DISCRIMINATION and PREJUDICES on TELEVISION

RESEARCH DOCUMENTATION The Black gangster and the Latino cleaning lady DISCRIMINATION AND PREJUDICES ON TELEVISION Ana Eckhardt Rodriguez The article summarises the stereo- of minority groups and the roles that nic minorities and religion (see, e.g., typical roles assigned to members are offered to them on television. Posi- Katz & Braly, 1993, 1935; Karlins et al., of minorities in TV and points out tive feedback and examples are then 1969). In earlier studies, results showed recognisable changes. presented. that black people and African Ameri- Eurodata (2018). One Television Year in the World. cans were characterised, for example, In 2017, the global average TV viewing Available at: https://www.eurodatatv.com/en/one- as ”athletic”, “rhythmic” (both posi- time stood at 2 hours and 56 minutes. television-year-world [4.3.18] tive stereotypes), but also as ”low in Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung (2010). Rassismus & Diskri- However, this figure varies a lot around minierung in Deutschland. Available at: https:// intelligence”. Pettigrew and Meertens the regions of the world (Asia: 2 hours heimatkunde.boell.de/sites/default/files/ dossier_ras- (1995) analysed both blatant and subtle and 25 minutes, Europe: 3 hours and 49 sismus_und_diskriminierung.pdf [8.10.18] racism in Western European countries. Browne Graves, Sherryl (1999). Television and preju- minutes, North America: 4 hours and dice reduction: When does television as a vicarious Amongst others they found that the 3 minutes; Eurodata, 2018). During this experience make a difference? Journal of Social Issues, French study participants voiced more 55(4), 707-727. time, people are often confronted with prejudice against North Africans than Harwood, Jake & Anderson, Karen (2002). -

Die Fremde) Phenomenon, That Is the Determining Factor

EN Foreword Textboxes offer a closer exploration of ideas and Honour crimes take place in many countries, within Her mother, speaking from within her own frame When We Leave issues raised by specific scenes in the film, and ask patriarchal communities. It is not religion but rather of reference, is the first to say: ‘You want too much’. a number of questions that invite debate about it. the patriarchal system, as a cultural and sociological She tells her daughter to ‘Stop dreaming!’ – being Europe’s cultural landscape is highly fragmented. the 23 official languages and the 27 Member States (Die Fremde) phenomenon, that is the determining factor. While a woman and a mother means making sacrifices. As dynamic as they may be, European sculptures, of the European Union during this month of May Winner of the European Parliament patriarchy is commonly found in Muslim com- But Umay’s immediate response is to challenge paintings, music, poetry, dance and literature are as part of the Festival of Europe. LUX Prize 2010 munities, these crimes cannot be laid at the door that idea. difficult to export outside their place of production. Background of Islam. The problem is an outmoded worldview As someone who has grown up in Germany, in Only a few artists and works make it abroad and find The aim is to create a European public space – a time A film by Feo Aladag that requires women and girls to submit to the contact with Western values, it is not surprising an audience outside their place of origin. and place where you, together with other European Germany, 2010; running time 119 minutes Honour crimes: bringing authority of the men in their families. -

Winner- Golden Bear (Top Prize) 54Th International Film Festival Berlin Winner – FIVE LOLAS (GERMAN ACADEMY AWARDS)

Winner- Golden Bear (Top Prize) 54th International Film Festival Berlin Winner – FIVE LOLAS (GERMAN ACADEMY AWARDS) Mongrel Media presents Head-On German Title: GEGEN DIE WAND A film by Fatih Akin with Sibel Kekilli, Birol Ünel, Catrin Striebeck, Güven Kiraç, Meltem Cumbul Running Time: 118 mins In German/Turkish with English subtitles Distribution 1028 Queen Street West Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR Tel: 416-488-4436 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] High res stills may be downloaded from http://mongrelmedia.com/press.html 1 THE CAST Cahit Birol Ünel Sibel Sibel Kekilli Maren Catrin Striebeck Seref Güven Kıraç Selma Meltem Cumbul Yilmaz Güner Cem Akin Birsen Güner Aysel Iscan Yunus Güner Demir Gökgöl Nico Stefan Gebelhoff Dr. Schiller Hermann Lause Lukas Adam Bousdoukos Ammer Ralph Misske Hüseyin Mehmet Kurtulu THE CREW Director/Script Fatih Akin Producers Ralph Schwingel Stefan Schubert Wüste Filmproduktion Coproducers NDR / arte CORAZÓN International Coproducers Fatih Akin Mehmet Kurtulu Andreas Thiel Story Editors Jeanette Würl, NDR Andreas Schreitmüller, arte Production Manager Ingrid Holzapfel Director of Photography Rainer Klausmann, bvk Editor Andrew Bird Assistant Director & Artistic Director Andreas Thiel Unit Photographer Kerstin Stelter Gaffer Torsten Lemke Sound Engineer Kai Lüde Set Design Tamo Kunz Costumes Katrin Aschendorf Make-Up Daniel Schröder & Nursen Balci Casting Mai Seck Sound Mix Richard Borowski Music Consultant Klaus Maeck 2 Synopsis 40-year-old Cahit (Birol Unel) is brought to a German psychiatric clinic after attempting suicide and sets out to start a new life, even as he longs for drugs and alcohol to numb his pain. -

Quarterly 4 · 2004

German Films Quarterly 4 · 2004 DOWNFALL by Oliver Hirschbiegel Competes for the OSCAR DIRECTORS’ PORTRAITS Dagmar Knoepfel & Oskar Roehler PRODUCERS' PORTRAIT Moneypenny Fosters New Talents SPECIAL REPORT German Films: Redefining the Role of Film Promotion Abroad german films quarterly 4/2004 focus on 4 GERMAN FILMS directors’ portraits 10 TRILOGY OF FEMININE STRENGTH A portrait of Dagmar Knoepfel 12 LEARNING TO LOVE LIFE A portrait of Oskar Roehler producers’ portrait 14 FOSTERING NEW TALENTS A portrait of Moneypenny Film actress’ portrait 16 TYPICAL GEMINI A portrait of Sibel Kekilli 18 news in production 22 CROSSING THE BRIDGE Fatih Akin 22 ERKAN & STEFAN III, FETTES MERCI FUER DIE LEICHE Michael Karen 23 GISELA Isabelle Stever 24 DIE HEXEN VOM PRENZLAUER BERG Diethard Kuester 24 ICH BIN EIN MOERDER Bernd Boehlich 25 KEIN HIMMEL UEBER AFRIKA Roland Suso Richter 26 MAX UND MORITZ Thomas Frydetzki 26 NVA Leander Haussmann 27 DER ROTE KAKADU Dominik Graf 28 DER SCHATZ DER WEISSEN FALKEN Christian Zuebert 28 SEHNSUCHT Valeska Grisebach 29 DIE WILDEN KERLE 2 Joachim Masannek new german films 30 24-7-365 Roland Reber 31 AUS DER TIEFE DES RAUMES Gil Mehmert 32 BERGKRISTALL ROCK CRYSTAL Joseph Vilsmaier 33 BIBI BLOCKSBERG UND DAS GEHEIMNIS DER BLAUEN EULEN BIBI BLOCKSBERG AND THE SECRET OF THE BLUE OWLS Franziska Buch 34 COWGIRL Mark Schlichter 35 ERBSEN AUF HALB 6 PEAS ON HALF PAST FIVE Lars Buechel 36 GOODBYE Steve Hudson 37 JENA PARADIES Marco Mittelstaedt 38 KAETHCHENS TRAUM Juergen Flimm 39 KATZE IM SACK LET THE CAT OUT OF THE BAG Florian -

Nation, Fantasy, and Mimicry: Elements of Political Resistance in Postcolonial Indian Cinema

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA Aparajita Sengupta University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sengupta, Aparajita, "NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA" (2011). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 129. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Aparajita Sengupta The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2011 NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aparajita Sengupta Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Michel Trask, Professor of English Lexington, Kentucky 2011 Copyright© Aparajita Sengupta 2011 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA In spite of the substantial amount of critical work that has been produced on Indian cinema in the last decade, misconceptions about Indian cinema still abound. Indian cinema is a subject about which conceptions are still muddy, even within prominent academic circles. The majority of the recent critical work on the subject endeavors to correct misconceptions, analyze cinematic norms and lay down the theoretical foundations for Indian cinema.