Identity, Cultural Representation and Feminism in the Movie Head-On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olive Films Presents

Mongrel Media Presents WHEN WE LEAVE A Film by Feo Aladag (118min., German, 2011) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html Cast Umay ….SIBEL KEKILLI Kader (Umay’s father) ….SETTAR TANRIÖGEN Halime (Umay’s mother) ….DERYA ALABORA Stipe (Umay’s colleague) ….FLORIAN LUKAS Mehmet(Umay’s older brother) ….TAMER YIGIT Acar (Umay’s younger brother) ….SERHAD CAN Rana (Umay’s younger sister) ….ALMILA BAGRIACIK Atife (Umay’s best friend) ….ALWARA HÖFELS Gül (Umay’s boss) ….NURSEL KÖSE Cem (Umay’s son) ….NIZAM SCHILLER Kemal (Umay’s husband) ….UFUK BAYRAKTAR Duran (Rana’s fiancé) ….MARLON PULAT Crew Script & Direction ….FEO ALADAG Producers ….FEO ALADAG, ZÜLI ALADAG Casting ….ULRIKE MÜLLER, HARIKA UYGUR, LUCY LENNOX Director of Photography ….JUDITH KAUFMANN Editor ….ANDREA MERTENS Production Design ….SILKE BUHR Costume Design ….GIOIA RASPÉ Sound ….JÖRG KIDROWSKI Score ….MAX RICHTER, STÉPHANE MOUCHA Make-up MONIKA MÜNNICH, MINA GHORAISHI Germany, 2010 Length: 119 minutes Format: CinemaScope 1:2.35 Sound system: Dolby Digital In German and in Turkish with English subtitles Synopsis What would you sacrifice for your family’s love? Your values? Your freedom? Your life? German-born Umay flees from her oppressive marriage in Istanbul, taking her young son Cem with her. She hopes to find a better life with her family in Berlin, but her unexpected arrival creates intense conflict. -

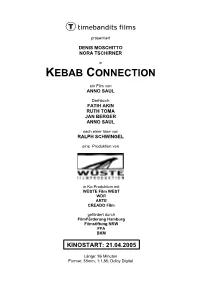

Kebab Connection

präsentiert DENIS MOSCHITTO NORA TSCHIRNER in KEBAB CONNECTION ein Film von ANNO SAUL Drehbuch FATIH AKIN RUTH TOMA JAN BERGER ANNO SAUL nach einer Idee von RALPH SCHWINGEL eine Produktion von in Ko-Produktion mit WÜSTE Film WEST WDR ARTE CREADO Film gefördert durch FilmFörderung Hamburg Filmstiftung NRW FFA BKM KINOSTART: 21.04.2005 Länge: 96 Minuten Format: 35mm, 1:1,85; Dolby Digital KEBAB CONNECTION VERLEIH timebandits films GmbH Stubenrauchstraße 2 14482 Potsdam Tel.: 0331 70 44 50 Fax.: 0331 70 44 529 [email protected] PRESSEBETREUUNG boxfish films Graf Rudolph Steiner GbR Senefelderstrasse 22 10437 Berlin Tel: 030 / 44044 751 Fax: 030 / 44044 691 E-mail: [email protected] Die offizielle Website des Films lautet: www.kebabconnection.de Weiteres Pressematerial steht online für Sie bereit unter: www.boxfish-films.de Seite 2 von 30 KEBAB CONNECTION INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Besetzung / Stab .......................................................................................4 Kurzinhalt / Pressenotiz.............................................................................5 Langinhalt..................................................................................................6 Produktionsnotizen ....................................................................................8 Interview mit Anno Saul.............................................................................11 Interview mit Nora Tschirner......................................................................14 Interview mit Denis Moschitto....................................................................16 -

Die Mechanik Der Erregung

Kultur SHOWGESCHÄFT Die Mechanik der Erregung Der inszenierte Wirbel um die Porno-Vergangenheit Sibel Kekillis, der deutschtürkischen Hauptdarstellerin im Berlinale-Siegerfilm „Gegen die Wand“, enthüllt vor allem eines: So freizügig sich eine Gesellschaft auch gibt – pseudoprüde Empörung zieht immer noch. KERSTIN STELTER / WÜSTE FILM / WÜSTE STELTER KERSTIN „Gegen die Wand“-Darsteller Ünel, Kekilli: Verschwitzte Enthüllungsarbeit nach dem Jubel über den Festivaltriumph uf der ersten Seite von „Bild“ bietet Hilfe an), tapfere Sibel (Wir sind stolz prangte am vergangenen Mittwoch auf sie) – das Blatt deklinierte den Fall nach AUschi Glas, 59, das sorgenfaltige allen Regeln des Boulevards durch. Reh. „Uschi Glas steht sündiger Film-Diva Dank der Enthüllung zog Kekilli, 23, in mutig bei“, lautete die Zeile. der Woche nach dem Triumph des „Gegen Heilige Uschi, da kam sie tatsächlich auf die Wand“-Melodrams bei der Berlinale- die Frontpage gewackelt, die Frau Sünde, Preisverleihung so viel Interesse auf sich, die „Bösartigkeit der menschlichen Natur“ dass der Regisseur des Films, der Ham- (Immanuel Kant). Ein anderes Wild, die burger Fatih Akin, neben der in Heilbronn rehäugige Sibel Kekilli, Hauptdarstellerin aufgewachsenen Jungschauspielerin nur des mit dem Goldenen Berlinale-Bären aus- noch eine Nebenrolle zu spielen schien. gezeichneten deutschen Films „Gegen die „Warum drehte die zarte Diva so harte Wand“, war auf dem Porno-Lotterlager er- Pornos?“, lautete die fürsorglich-kultur- wischt worden – „Bild“ fuhr seine neueste kritische Schlüsselfrage der „Bild“-Kam- Kampagne: Schlimme Sibel (Wie kann sie uns so täuschen), arme Sibel (Die Eltern „Bild“-Zeitung vom 17. Februar (Ausriss) verstoßen sie), hilfsbedürftige Sibel (Uschi Schlimme Sibel, arme Sibel 160 der spiegel 9/2004 pagne. -

The Black Gangster and the Latino Cleaning Lady DISCRIMINATION and PREJUDICES on TELEVISION

RESEARCH DOCUMENTATION The Black gangster and the Latino cleaning lady DISCRIMINATION AND PREJUDICES ON TELEVISION Ana Eckhardt Rodriguez The article summarises the stereo- of minority groups and the roles that nic minorities and religion (see, e.g., typical roles assigned to members are offered to them on television. Posi- Katz & Braly, 1993, 1935; Karlins et al., of minorities in TV and points out tive feedback and examples are then 1969). In earlier studies, results showed recognisable changes. presented. that black people and African Ameri- Eurodata (2018). One Television Year in the World. cans were characterised, for example, In 2017, the global average TV viewing Available at: https://www.eurodatatv.com/en/one- as ”athletic”, “rhythmic” (both posi- time stood at 2 hours and 56 minutes. television-year-world [4.3.18] tive stereotypes), but also as ”low in Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung (2010). Rassismus & Diskri- However, this figure varies a lot around minierung in Deutschland. Available at: https:// intelligence”. Pettigrew and Meertens the regions of the world (Asia: 2 hours heimatkunde.boell.de/sites/default/files/ dossier_ras- (1995) analysed both blatant and subtle and 25 minutes, Europe: 3 hours and 49 sismus_und_diskriminierung.pdf [8.10.18] racism in Western European countries. Browne Graves, Sherryl (1999). Television and preju- minutes, North America: 4 hours and dice reduction: When does television as a vicarious Amongst others they found that the 3 minutes; Eurodata, 2018). During this experience make a difference? Journal of Social Issues, French study participants voiced more 55(4), 707-727. time, people are often confronted with prejudice against North Africans than Harwood, Jake & Anderson, Karen (2002). -

Die Fremde) Phenomenon, That Is the Determining Factor

EN Foreword Textboxes offer a closer exploration of ideas and Honour crimes take place in many countries, within Her mother, speaking from within her own frame When We Leave issues raised by specific scenes in the film, and ask patriarchal communities. It is not religion but rather of reference, is the first to say: ‘You want too much’. a number of questions that invite debate about it. the patriarchal system, as a cultural and sociological She tells her daughter to ‘Stop dreaming!’ – being Europe’s cultural landscape is highly fragmented. the 23 official languages and the 27 Member States (Die Fremde) phenomenon, that is the determining factor. While a woman and a mother means making sacrifices. As dynamic as they may be, European sculptures, of the European Union during this month of May Winner of the European Parliament patriarchy is commonly found in Muslim com- But Umay’s immediate response is to challenge paintings, music, poetry, dance and literature are as part of the Festival of Europe. LUX Prize 2010 munities, these crimes cannot be laid at the door that idea. difficult to export outside their place of production. Background of Islam. The problem is an outmoded worldview As someone who has grown up in Germany, in Only a few artists and works make it abroad and find The aim is to create a European public space – a time A film by Feo Aladag that requires women and girls to submit to the contact with Western values, it is not surprising an audience outside their place of origin. and place where you, together with other European Germany, 2010; running time 119 minutes Honour crimes: bringing authority of the men in their families. -

Winner- Golden Bear (Top Prize) 54Th International Film Festival Berlin Winner – FIVE LOLAS (GERMAN ACADEMY AWARDS)

Winner- Golden Bear (Top Prize) 54th International Film Festival Berlin Winner – FIVE LOLAS (GERMAN ACADEMY AWARDS) Mongrel Media presents Head-On German Title: GEGEN DIE WAND A film by Fatih Akin with Sibel Kekilli, Birol Ünel, Catrin Striebeck, Güven Kiraç, Meltem Cumbul Running Time: 118 mins In German/Turkish with English subtitles Distribution 1028 Queen Street West Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR Tel: 416-488-4436 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] High res stills may be downloaded from http://mongrelmedia.com/press.html 1 THE CAST Cahit Birol Ünel Sibel Sibel Kekilli Maren Catrin Striebeck Seref Güven Kıraç Selma Meltem Cumbul Yilmaz Güner Cem Akin Birsen Güner Aysel Iscan Yunus Güner Demir Gökgöl Nico Stefan Gebelhoff Dr. Schiller Hermann Lause Lukas Adam Bousdoukos Ammer Ralph Misske Hüseyin Mehmet Kurtulu THE CREW Director/Script Fatih Akin Producers Ralph Schwingel Stefan Schubert Wüste Filmproduktion Coproducers NDR / arte CORAZÓN International Coproducers Fatih Akin Mehmet Kurtulu Andreas Thiel Story Editors Jeanette Würl, NDR Andreas Schreitmüller, arte Production Manager Ingrid Holzapfel Director of Photography Rainer Klausmann, bvk Editor Andrew Bird Assistant Director & Artistic Director Andreas Thiel Unit Photographer Kerstin Stelter Gaffer Torsten Lemke Sound Engineer Kai Lüde Set Design Tamo Kunz Costumes Katrin Aschendorf Make-Up Daniel Schröder & Nursen Balci Casting Mai Seck Sound Mix Richard Borowski Music Consultant Klaus Maeck 2 Synopsis 40-year-old Cahit (Birol Unel) is brought to a German psychiatric clinic after attempting suicide and sets out to start a new life, even as he longs for drugs and alcohol to numb his pain. -

Quarterly 4 · 2004

German Films Quarterly 4 · 2004 DOWNFALL by Oliver Hirschbiegel Competes for the OSCAR DIRECTORS’ PORTRAITS Dagmar Knoepfel & Oskar Roehler PRODUCERS' PORTRAIT Moneypenny Fosters New Talents SPECIAL REPORT German Films: Redefining the Role of Film Promotion Abroad german films quarterly 4/2004 focus on 4 GERMAN FILMS directors’ portraits 10 TRILOGY OF FEMININE STRENGTH A portrait of Dagmar Knoepfel 12 LEARNING TO LOVE LIFE A portrait of Oskar Roehler producers’ portrait 14 FOSTERING NEW TALENTS A portrait of Moneypenny Film actress’ portrait 16 TYPICAL GEMINI A portrait of Sibel Kekilli 18 news in production 22 CROSSING THE BRIDGE Fatih Akin 22 ERKAN & STEFAN III, FETTES MERCI FUER DIE LEICHE Michael Karen 23 GISELA Isabelle Stever 24 DIE HEXEN VOM PRENZLAUER BERG Diethard Kuester 24 ICH BIN EIN MOERDER Bernd Boehlich 25 KEIN HIMMEL UEBER AFRIKA Roland Suso Richter 26 MAX UND MORITZ Thomas Frydetzki 26 NVA Leander Haussmann 27 DER ROTE KAKADU Dominik Graf 28 DER SCHATZ DER WEISSEN FALKEN Christian Zuebert 28 SEHNSUCHT Valeska Grisebach 29 DIE WILDEN KERLE 2 Joachim Masannek new german films 30 24-7-365 Roland Reber 31 AUS DER TIEFE DES RAUMES Gil Mehmert 32 BERGKRISTALL ROCK CRYSTAL Joseph Vilsmaier 33 BIBI BLOCKSBERG UND DAS GEHEIMNIS DER BLAUEN EULEN BIBI BLOCKSBERG AND THE SECRET OF THE BLUE OWLS Franziska Buch 34 COWGIRL Mark Schlichter 35 ERBSEN AUF HALB 6 PEAS ON HALF PAST FIVE Lars Buechel 36 GOODBYE Steve Hudson 37 JENA PARADIES Marco Mittelstaedt 38 KAETHCHENS TRAUM Juergen Flimm 39 KATZE IM SACK LET THE CAT OUT OF THE BAG Florian -

Fox in a Hole

ALEKSANDAR LUNA MARIA ANDREAS SIBEL PETROVIĆ JORDAN HOFSTÄTTER LUST KEKILLI A FILM BY ARMAN T. RIAHI GOLDEN GIRLS FILM PRESENTS „FOX IN A HOLE“ WITH ALEKSANDAR PETROVIĆ MARIA HOFSTÄTTER LUNA JORDAN SIBEL KEKILLI ANDREAS LUST KARL FISCHER ANICA DOBRA AND FARIS RAHOMA D.O.P MARIO MINICHMAYR PRODUCTION DESIGN MARTIN REITER COSTUME MONIKA BUTTINGER MAKE-UP ARTIST BIRGIT BERANEK EDITING KARINA RESSLER AEA CASTING NICOLE SCHMIED CHERELLE JANECEK DENISE TEIPEL SOUND ATANAS TCHOLAKOV MANUEL MEICHSNER NILS KIRCHHOFF POSTPRODUCTION SUPERVISOR DANIEL PAZDERKA PRODUCERS ARASH T. RIAHI & KARIN C. BERGER WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY ARMAN T. RIAHI FILMLADEN FILM DISTRIBUTION presents a production of Golden Girls Film FOX IN A HOLE Written & Directed by Arman T. Riahi CINEMA RELEASE: 2021 (Austria) Press Relations: apomat* office for communication GmbH Mahnaz Tischeh [email protected] Phone: +43 699 1190 2257 Film Distribution: Filmladen Film Distribution Mariahilfer Strasse 58/7 A-1070 Vienna +43 1 523 43 62-0 [email protected] Production Company: Golden Girls Film Produktion & Film Services GmbH Seidengasse 15/3/20 A-1070 Vienna +43 1 810 56 36 [email protected] www.goldengirls.at 2 Cast ALEKSANDAR PETROVIĆ, MARIA HOFSTÄTTER, LUNA JORDAN, ANDREAS LUST, SIBEL KEKILLI, KARL FISCHER, LUKAS WATZL, MICHAELA SCHAUSBERGER, ANICA DOBRA, FARIS RAHOMA, LJUBIŠA GRUJČIĆ, u.a. Inspired by the experiences of the special education teacher of Viennese prison Josefstadt Wolfgang Riebniger Credits Director & Screenplay: ARMAN T. RIAHI Cinematography: MARIO MINICHMAYR Production Design: MARTIN REITER Costume: MONIKA BUTTINGER Make-up: BIRGIT BERANEK Editing: KARINA RESSLER Sound: ATANAS TCHOLAKOV Light: JAKOB BALLINGER Casting: NICOLE SCHMIED Producers: ARASH T. RIAHI & KARIN C. -

DVD-Liste SPIELFILME

DVD-Liste Der Bibliothek des Goethe-Instituts Krakau SPIELFILME Abgebrannt / [Darsteller:] Maryam Zaree, Tilla Kratochwil, Lukas Steltner... Regie & Buch: Verena S. Freytag. Kamera: Ali Olcay Gözkaya. Musik: Roland Satterwhite Frankfurt: PFMedia, 2012.- Bildtonträger.- 1 DVD-Video (Ländercode 0, 103 Min.) : farb. Sprache: dt. - Untertitel: engl., franz.- FSK-Freigabe ab 12 Jahren. - Spielfilm. Deutschland. 2010 The Adventures of Werner Holt / Darsteller: Klaus-Peter Thiele, Manfred Karge, Arno Wyzniewski ... Kamera: Rolf Sohre. Musik: Gerhard Wohlgemuth. Drehbuch: Claus Küchenmeister... Regie: Joachim Kunert. [Nach dem Roman von Dieter Noll] - 1 DVD (163 Min.) : s/w. Dolby digital EST: Die@Abenteuer des Werner Holt <dt.> Sprache: dt. - Untertitel: eng. - Extras: Biografien und Filmografien. - Spielfilm, Literaturverfilmung. DDR. 1964 Abfallprodukte der Liebe / Ein Film von Werner Schroeter. Mit Anita Cerquetti, Martha Mödl, Rita Gorr... Berlin: Filmgalerie 451, 2009.- Bildtonträger.- 1 DVD Abschied : Brechts letzter Sommer / Josef Bierbichler, Monika Bleibtreu, Elfriede Irrall ... Buch: Klaus Pohl. Kamera: Edward KÚosiõski. Musik: John Cale. Regie: Jan Schütte München: Goethe-Institut e.V., 2013.- Bildtonträger.- 1 DVD (PAL, Ländercode-frei, 88 Min.) : farb., DD 2.0 Stereo Sprache: dt. - Untertitel: dt., engl., span., franz., port.. - Spielfilm. Deutschland. 2000 Absolute Giganten / ein Film von Sebastian Schipper. [Darst.]: Frank Giering, Florian Lukas, Antoine Monot, Julia Hummer. Kamera: Frank Griebe. Musik: The Notwist. Drehbuch und Regie: Sebastian Schipper Notwist München: Goethe-Institut e.V., 2012.- Bildtonträger.- 1 DVD (PAL, Ländercode-frei, 81 Min.) : farb., DD 2.0 Sprache: dt. - Untertitel: dt., span., port., engl., franz., ital., indo.. - Spielfilm. Deutschland. 1999 Absurdistan / ein Film von Veit Helmer. Mit: Maximilian Mauff, Kristýna MaléÂová und Schauspielern aus 18 Ländern. -

The End of Imperialism Was the Birth of Nationalism, a Wave of Rising

New German Identity: Reworking the Past and Defining the Present in Contemporary German Cinema Constance McCarney Dr. Robert Gregg Spring 2008 General University Honors McCarney 2 The end of imperialism was the birth of nationalism, a wave of rising consciousness that swept over the conquered areas of the world and brought them to their feet with a defiant cry, “We are a Nation!” These new nations, almost all multiethnic states, struggled in defining themselves, found themselves locked in civil wars over what the citizen of this nation looked like and who s/he was. The old nations, locked in a Cold War, looked on, confident in their own national cohesion and unity. But the end of the Cold War proved to be the birth of complicated new identity concerns for Europe. Yugoslavia splintered in terrible ethnic conflict. France rioted over the expression of religious affiliation. Germany tried desperately to salvage the hope that brought down the Wall and stitch itself back together. For Germany the main questions of identity linger, not only who is a German, but what does it mean to be German? In the aftermath of the great upheavals in Germany’s recent past, the Second World War and the fall of the Third Reich, German films did their best to ignore these questions of identity and the complications of the past. But in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, a New German Cinema arose that sought to work through the complex issues of West Germany: the legacy of the Nazi Past, American occupation, the Berlin Wall and divided Germany, the radicalism of the time period in a global context, and the civil rights movements, particularly the women’s movement. -

Productlistings

02-05 Berlin listings_lg_edit c:L02THR_Fri020510_EW 2/4/10 11:55 AM Page L-2 NuImage/Millennium Films’ “The Mechanic” ProductListi ngs On Offer: THE BOXER (U.S.A./ On Offer: THE BAIT (U.S.A./Poland; 27 FILMS PRODUCTION LISTINGS NOTE Germany; action-adventure) Director: thriller) Director: Dariusz Zawislak; cast: Phone: 49-30-847-116-60 Thomas Jahn; cast: Stacy Keach, Joshua Faye Dyaway, Sonia Bohosiewicz. (90 On Offer: FRANCUSKI (Germany/ Dallas. (90 mins.; screening; debuting) mins.; screening; debuting) Listings represent product Austria/Poland; drama) Director: Goran THE LOST SAMARITAN (U.S.A./ THE MAGIC STONE (family) Director: on offer by companies that Rebic; cast: Samuel Finzi, Lars Rudolph. Germany; action-adventure) Director: Jowita Gondek; cast: Faye Dunaway, submitted titles to (development; presales; debuting) Thomas Jahn; cast: Ian Somerhalder, Majka Jezowska. (postproduction; prod - MR. LU’S BLUES (Germany/Sweden/ THR.com/listings. Ruta Gedmintas. (90 mins.; screener uct reel/trailer; debuting) China; romance) Director: Maria Von Submissions were limited cassette/DVD; debuting) Heland (development; presales; debuting) to two of the following: AFFINITY INTL. attending executives, 6 SALES ADRIANA CHIESA Berlin Office: Ritz Carlton Suite 550 ENTERPRISES Office Phone: 49-03-033-777-56 projects and cast members Berlin Office: Marriott Hotel, 1st Floor, Berlin Office: MGB 135 Attending: Bill Lischak, COO; Brian per project. Participating Office #100 Office Phone: 49-30-22000-1127 Office Phone: 49-03-024-649-7400 O’shea, president, worldwide distribution companies may have Attending: Mar Abadin, head of sales; Attending: Adriana Chiesa Di Palma, Phone: 310-652-0999 additional films on offer. Marina Fuentes, partner president; Rossella Gori, head of interna - On Offer: FROM PRADA TO NADA Phone: -34-91-636-10-54 tional sales (U.S.A.; romance) Director: Angel Gracia; On Offer: THE DANCER & THE THIEF Phone: -39-06-808-6052 cast: Adriana Barraza, Camilla Belle. -

Memorias Del Club De Cine: Más Allá De La Pantalla 2008-2015

Memorias del Club de Cine: Más allá de la pantalla 2008-2015 MAURICIO LAURENS UNIVERSIDAD EXTERNADO DE COLOMBIA Decanatura Cultural © 2016, UNIVERSIDAD EXTERNADO DE COLOMBIA Calle 12 n.º 1-17 Este, Bogotá Tel. (57 1) 342 0288 [email protected] www.uexternado.edu.co ISSN 2145 9827 Primera edición: octubre del 2016 Diseño de cubierta: Departamento de Publicaciones Composición: Precolombi EU-David Reyes Impresión y encuadernación: Digiprint Editores S.A.S. Tiraje de 1 a 1.200 ejemplares Impreso en Colombia Printed in Colombia Cuadernos culturales n.º 9 Universidad Externado de Colombia Juan Carlos Henao Rector Miguel Méndez Camacho Decano Cultural 7 CONTENIDO Prólogo (1) Más allá de la pantalla –y de su pedagogía– Hugo Chaparro Valderrama 15 Prólogo (2) El cine, una experiencia estética como mediación pedagógica Luz Marina Pava 19 Metodología y presentación 25 Convenciones 29 CUADERNOS CULTURALES N.º 9 8 CAPÍTULOS SEMESTRALES: 2008 - 2015 I. RELATOS NUEVOS Rupturas narrativas 31 I.1 El espejo - I.2 El diablo probablemente - I.3 Padre Padrone - I.4 Vacas - I.5 Escenas frente al mar - I.6 El almuerzo desnudo - I.7 La ciudad de los niños perdidos - I.8 Autopista perdida - I.9 El gran Lebowski - I.10 Japón - I.11 Elephant - I.12 Café y cigarrillos - I.13 2046: los secretos del amor - I.14 Whisky - I.15 Luces al atardecer. II. DEL LIBRO A LA PANTALLA Adaptaciones escénicas y literarias 55 II.1 La bestia humana - II.2 Hamlet - II.3 Trono de sangre (Macbeth) - II.4 El Decamerón - II.5 Muerte en Venecia - II.6 Atrapado sin salida - II.7 El resplandor - II.8 Cóndores no entierran todos los días - II.9 Habitación con vista - II.10 La casa de los espíritus - II.11 Retrato de una dama - II.12 Letras prohibidas - II.13 Las horas.