A Systematic Review of Animal Predation Creating Pierced Shells: Implications for the Archaeological Record of the Old World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molluscan Studies

Journal of The Malacological Society of London Molluscan Studies Journal of Molluscan Studies (2014) 80: 412–419. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyu037 Advance Access publication date: 20 June 2014 Morphological expression and histological analysis of imposex in Gemophos viverratus (Kiener, 1834) (Gastropoda: Buccinidae): a new bioindicator of tributyltin pollution on the West African coast Ruy M. A. Lopes-dos-Santos1, Corrine Almeida2, Maria de Lourdes Pereira3, Carlos M. Barroso4 and Susana Galante-Oliveira4 1Biology Department, University of Aveiro, Campus Universita´rio de Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal; 2Department of Engineering and Sea Sciences (DECM), University of Cabo Verde, Campus da Ribeira de Julia˜o, CP 163 Sa˜o Vicente, Cabo Verde; 3Biology Department & CICECO, University of Aveiro, Campus Universita´rio de Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal; and 4Biology Department & CESAM, University of Aveiro, Campus Universita´rio de Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal Correspondence: R. M. A. Lopes-dos-Santos; e-mail: [email protected] (Received 8 January 2014; accepted 24 March 2014) ABSTRACT We describe the reproductive system and morphological expression of imposex in the marine gastropod Gemophos viverratus (Kiener, 1834) for the first time. This species can be used as a bioindicator of tributyl- tin (TBT) pollution on the west coast of Africa, a region for which there is a lack of information regard- ing levels and impacts of TBT pollution. Adult G. viverratus were collected between August 2012 and July 2013 in Sa˜o Vicente Island (Republic of Cabo Verde), at pristine sites on the northeastern and eastern coasts and at Porto Grande Bay, the major harbour in the country. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Tese1997vol1.Pdf

Dedicado à Cristina e ao João David Advertência prévia Este trabalho corresponde à dissertação escrita pelo autor para obtenção do grau de doutoramento em Pré-História pela Universidade de Lisboa. A sua redacção ficou concluída em Abril de 1995, e a respectiva arguição teve lugar em Novembro do mesmo ano. A versão agora publicada beneficiou de pequenos ajustamentos do texto, de uma actualização da biliografia e do acrescento de alguns elementos de informação novos, nomeadamente no que diz respeito a datações radiométricas. A obra compreende dois volumes. No volume II agruparam-se os capítulos sobre a história da investigação e a metodologia utilizada na análise dos materiais líticos, bem como os estudos monográficos das diferentes colecções. No volume I, sintetizaram-se as conclusões derivadas desses estudos, e procurou-se integrá-las num quadro histórico e geográfico mais lato, o das sociedades de caçadores do Paleolítico Superior do Sudoeste da Europa. A leitura do volume I é suficiente para a aquisição de uma visão de conjunto dos conhecimentos actuais respeitantes a este período em Portugal. Uma tal leitura deve ter em conta, porém, que essa síntese pressupõe uma crítica das fontes utilizadas. Em Arqueologia, o instrumento dessa crítica é a análise tafonómica dos sítios e espólios. A argumentação sobre as respectivas condições de jazida é desenvolvida no quadro dos estudos apresentados no volume II. É neles que deve ser buscada a razão de ser das opções tomadas quanto à caracterização dos contextos (ocupações singulares, palimpsestos de ocupações múltiplas), à sua homogeneidade (uma só época ou várias épocas), à sua integridade (em posição primária ou secundária), à sua representatividade (universo ou amostra, recuperação integral ou parcial) e à sua cronologia (ou cronologias). -

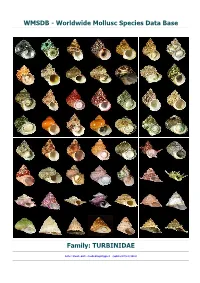

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Glossary of Major Terms and Concepts

Glossary of Major Terms and Concepts The following terms and concepts form the core of much of this book. Generally, they appear in boldface type in the text. The chapters in which they are more fully discussed are also given. Acceleration: Faster rate of developmenral evenrs (at any level: cell, organ, individual) in the descendanr; produces peramorphie traits when expressed in the adult pheno type. (Chapters 1 and 2) Allometric heterochrony: Change in a trair as a function of size (as opposed to a function of age in " true" heterochrony); it is useful as adescriptor and can be inrerpretive considering that body size is often a beuer metric of " inrrinsic" age than chronologi cal age. The same categories apply as in " true" heterochrony, only the adjective "allometric" is prefixed: e.g. , " allometric progenesis" is when the descendant ter minates growth at a smaller size (as opposed to age) than the ancestor. (Chapter 2) Allometry: The study of size and shape, usually using biometrie data; the change in size and shape observed. Basic kinds of allometric change include the following. Com plex allometry: occurs when the ratio of the specific growth rates of the traits compared are not constant, a log-log plot comparing the traits will not yield a straight line (i.e., " k" in the allometric formula is inconstanr). Isometry: occurs when there is no change in shape with size increase; that is, when the traits being compared on a log-log plot yield a straight line with a slope (k in the allometric formula) that is effectively equal to 1. -

Shells from the Excavation of Yavne-Yam (North)

‘Atiqot 81, 2015 SHELLS FROM THE EXCAVATION OF YAVNE-YAM (NORTH) HENK K. MIENIS1 The salvage excavation at Yavne-Yam (North), Only the freshwater mussel Unio mancus carried out by Moshe Ajami and Uzi ‘Ad (this eucirrus has disappeared from Nahal Soreq due volume),2 yielded several samples of shells. to severe pollution of its waters in recent times. The presence of the land snail Theba pisana Material and Methods within a Roman-period context at Yavne-Yam The eight mollusc samples submitted for (North) is interesting. Heller and Tchernov identification were collected in six loci: three in (1978) considered Theba pisana a possible Area B and three in Area C. Most of the shells ancient introduction, since they did not find it could be identified on site. In a few cases, shell among the Pleistocene land snails occurring fragments were compared with recent samples in the coastal plain of Israel. However, in the Mollusc Collection of Tel Aviv University. that species has already been found in the The bulk of the sample was collected in the so- underwater Neolithic wells off ‘Atlit (Mienis, called shell-pit in Area C (L321; see Ajami and unpublished). ‘Ad, this volume: Plan 8); only the presence of None of the marine shells show clear-cut the various species was noted. markings of manipulation; however, some of the Glycymeris valves with a hole in the umbo Results might have served as a shell pendant. The The results of the studied material are listed in same is true for some of the holed valves of systematic order in Table 1. -

Portadas 21 (1)

© Sociedad Española de Malacología Iberus , 21 (1): 115-127, 2003 Four new Euthria (Mollusca, Buccinidae) from the Cape Verde archipelago, with comments on the validity of the genus Cuatro nuevas Euthria (Mollusca, Buccinidae) del archipiélago de Cabo Verde con comentarios sobre la validez del género Emilio ROLÁN *, António MONTEIRO ** and Koen FRAUSSEN *** Recibido el 2-XII-2002. Aceptado el 22-I-2003 ABSTRACT Four species, collected in the Cape Verde Islands, are described as new and assigned to the genus Euthria M. E. Gray, 1830. The new species are compared with other taxa from the Mediterranean Sea and the Cape Verde Archipelago. The genera Euthria , and Buccin - ulum are compared and the significance of the differences between them is discussed, leading to the conclusion that both genera are valid and should be kept separated. RESUMEN Se describen cuatro especies nuevas del género Euthria M. E. Gray, 1830 recogidas en aguas circalitorales del archipiélago de Cabo Verde. Las nuevas especies son compara - das con otros taxones congenéricos existentes en el Mediterráneo y en el propio archip - iélago. Recientemente, el género Euthria, únicamente conocido del Atlántico oriental, ha sido sinonimizado con Buccinulum , que posee especies en el Indo-Pacífico, por lo que se comparan ambos géneros y se discute el valor de las diferencias entre ellos, considerando finalmente que ambos son válidos, y deben mantenerse separados. KEY WORDS: Euthria , Buccinulum , Cape Verde Archipelago, new taxa. PALABRAS CLAVE : Euthria , Buccinulum , Archipiélago de Cabo Verde, nuevos táxones. INTRODUCTION During the last few years, the genus them separate, as commented upon in Euthria Gray, 1850 has frequently been “Remarks” of this paper. -

The Evolution of the Molluscan Biota of Sabaudia Lake: a Matter of Human History

SCIENTIA MARINA 77(4) December 2013, 649-662, Barcelona (Spain) ISSN: 0214-8358 doi: 10.3989/scimar.03858.05M The evolution of the molluscan biota of Sabaudia Lake: a matter of human history ARMANDO MACALI 1, ANXO CONDE 2,3, CARLO SMRIGLIO 1, PAOLO MARIOTTINI 1 and FABIO CROCETTA 4 1 Dipartimento di Biologia, Università Roma Tre, Viale Marconi 446, I-00146 Roma, Italy. 2 IBB-Institute for Biotechnology and Bioengineering, Center for Biological and Chemical Engineering, Instituto Superior Técnico (IST), 1049-001, Lisbon, Portugal. 3 Departamento de Ecoloxía e Bioloxía Animal, Universidade de Vigo, Lagoas-Marcosende, Vigo E-36310, Spain. 4 Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, Villa Comunale, I-80121 Napoli, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY: The evolution of the molluscan biota in Sabaudia Lake (Italy, central Tyrrhenian Sea) in the last century is hereby traced on the basis of bibliography, museum type materials, and field samplings carried out from April 2009 to Sep- tember 2011. Biological assessments revealed clearly distinct phases, elucidating the definitive shift of this human-induced coastal lake from a freshwater to a marine-influenced lagoon ecosystem. Records of marine subfossil taxa suggest that previous accommodations to these environmental features have already occurred in the past, in agreement with historical evidence. Faunal and ecological insights are offered for its current malacofauna, and special emphasis is given to alien spe- cies. Within this framework, Mytilodonta Coen, 1936, Mytilodonta paulae Coen, 1936 and Rissoa paulae Coen in Brunelli and Cannicci, 1940 are also considered new synonyms of Mytilaster Monterosato, 1884, Mytilaster marioni (Locard, 1889) and Rissoa membranacea (J. -

Systematics and Phylogenetic Species Delimitation Within Polinices S.L. (Caenogastropoda: Naticidae) Based on Molecular Data and Shell Morphology

Org Divers Evol (2012) 12:349–375 DOI 10.1007/s13127-012-0111-5 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Systematics and phylogenetic species delimitation within Polinices s.l. (Caenogastropoda: Naticidae) based on molecular data and shell morphology Thomas Huelsken & Daniel Tapken & Tim Dahlmann & Heike Wägele & Cynthia Riginos & Michael Hollmann Received: 13 April 2011 /Accepted: 10 September 2012 /Published online: 19 October 2012 # Gesellschaft für Biologische Systematik 2012 Abstract Here, we present the first phylogenetic analysis of callus) to be informative, while many characters show a a group of species taxonomically assigned to Polinices high degree of homoplasy (e.g. umbilicus, shell form). sensu latu (Naticidae, Gastropoda) based on molecular data Among the species arranged in the genus Polinices s.s., four sets. Polinices s.l. represents a speciose group of the infau- conchologically very similar taxa often subsumed under the nal gastropod family Naticidae, including species that have common Indo-Pacific species P. mammilla are separated often been assigned to subgenera of Polinices [e.g. P. distinctly in phylogenetic analyses. Despite their striking (Neverita), P. (Euspira), P.(Conuber) and P. (Mammilla)] conchological similarities, none of these four taxa are relat- based on conchological data. The results of our molecular ed directly to each other. Additional conchological analyses phylogenetic analysis confirm the validity of five genera, of available name-bearing type specimens and type figures Conuber, Polinices, Mammilla, Euspira and Neverita, in- reveal the four “mammilla”-like white Polinices species to cluding four that have been used previously mainly as sub- include true P. mammilla and three additional species, which genera of Polinices s.l. -

From the Late Neogene of Northwestern France

Cainozoic Research, 15(1-2), pp. 75-122, October 2015 75 The family Nassariidae (Gastropoda: Buccinoidea) from the late Neogene of northwestern France Frank Van Dingenen1, Luc Ceulemans2, Bernard M. Landau3, 5& Carlos Marques da Silva4 1 Cambeenboslaan A 11, B-2960 Brecht, Belgium; email: [email protected] 2 Avenue Général Naessens de Loncin 1, B-1330 Rixensart, Belgium; email: [email protected] 3 Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, Netherlands; Instituto Dom Luiz da Universidade de Lisboa, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal; and International Health Centres, Av. Infante de Henrique 7, Areias São João, P-8200 Albufeira, Portugal; email: [email protected] 4 Departamento de Geologia e Instituto Dom Luiz, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisbon, Portugal; [email protected] 5 corresponding author Received 7 July 2015, revised version accepted 4 August 2015 In this paper we revise the nassariid Plio-Pleistocene assemblages of northwestern France. Twenty-eight species are recorded, of which eleven are described as new; Nassarius brebioni nov. sp., Nassarius landreauensis nov. sp., Nassarius merlei nov. sp., Nassarius pacaudi nov. sp., Nassarius palumbis nov. sp., Nassarius columbinus nov. sp., Nassarius turpis nov. sp., Nassarius poteriensis nov. sp., Nassarius plainei nov. sp., Nassarius martae nov. sp., Nassarius gendryi nov. sp., five are left in open nomenclature. Two nassariid genera are recognised (Nassarius and Demoulia). The ‘Redonian’ assemblages and localities are grouped in four assemblages (Assemblages I – IV) corresponding to the four major stratigraphic groups of deposits recognised in the post mid-Miocene sequences of northwestern France. -

Mollusc Fauna of Iskenderun Bay with a Checklist of the Region

www.trjfas.org ISSN 1303-2712 Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 12: 171-184 (2012) DOI: 10.4194/1303-2712-v12_1_20 SHORT PAPER Mollusc Fauna of Iskenderun Bay with a Checklist of the Region Banu Bitlis Bakır1, Bilal Öztürk1*, Alper Doğan1, Mesut Önen1 1 Ege University, Faculty of Fisheries, Department of Hydrobiology Bornova, Izmir. * Corresponding Author: Tel.: +90. 232 3115215; Fax: +90. 232 3883685 Received 27 June 2011 E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 13 December 2011 Abstract This study was performed to determine the molluscs distributed in Iskenderun Bay (Levantine Sea). For this purpose, the material collected from the area between the years 2005 and 2009, within the framework of different projects, was investigated. The investigation of the material taken from various biotopes ranging at depths between 0 and 100 m resulted in identification of 286 mollusc species and 27542 specimens belonging to them. Among the encountered species, Vitreolina cf. perminima (Jeffreys, 1883) is new record for the Turkish molluscan fauna and 18 species are being new records for the Turkish Levantine coast. A checklist of Iskenderun mollusc fauna is given based on the present study and the studies carried out beforehand, and a total of 424 moluscan species are known to be distributed in Iskenderun Bay. Keywords: Levantine Sea, Iskenderun Bay, Turkish coast, Mollusca, Checklist İskenderun Körfezi’nin Mollusca Faunası ve Bölgenin Tür Listesi Özet Bu çalışma İskenderun Körfezi (Levanten Denizi)’nde dağılım gösteren Mollusca türlerini tespit etmek için gerçekleştirilmiştir. Bu amaçla, 2005 ve 2009 yılları arasında sürdürülen değişik proje çalışmaları kapsamında bölgeden elde edilen materyal incelenmiştir.