Marine Shell Working at Harlaa, Ethiopia, and the Implications for Red Sea Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cone Collector N°23

THE CONE COLLECTOR #23 October 2013 THE Note from CONE the Editor COLLECTOR Dear friends, Editor The Cone scene is moving fast, with new papers being pub- António Monteiro lished on a regular basis, many of them containing descrip- tions of new species or studies of complex groups of species that Layout have baffled us for many years. A couple of books are also in André Poremski the making and they should prove of great interest to anyone Contributors interested in Cones. David P. Berschauer Pierre Escoubas Our bulletin aims at keeping everybody informed of the latest William J. Fenzan developments in the area, keeping a record of newly published R. Michael Filmer taxa and presenting our readers a wide range of articles with Michel Jolivet much and often exciting information. As always, I thank our Bernardino Monteiro many friends who contribute with texts, photos, information, Leo G. Ros comments, etc., helping us to make each new number so inter- Benito José Muñoz Sánchez David Touitou esting and valuable. Allan Vargas Jordy Wendriks The 3rd International Cone Meeting is also on the move. Do Alessandro Zanzi remember to mark it in your diaries for September 2014 (defi- nite date still to be announced) and to plan your trip to Ma- drid. This new event will undoubtedly be a huge success, just like the two former meetings in Stuttgart and La Rochelle. You will enjoy it and of course your presence is indispensable! For now, enjoy the new issue of TCC and be sure to let us have your opinions, views, comments, criticism… and even praise, if you feel so inclined. -

References Please Help Making This Preliminary List As Complete As Possible!

Cypraeidae - important references Please help making this preliminary list as complete as possible! ABBOTT, R.T. (1965) Cypraea arenosa Gray, 1825. Hawaiian Shell News 14(2):8 ABREA, N.S. (1980) Strange goings on among the Cypraea ziczac. Hawaiian Shell News 28 (5):4 ADEGOKE, O.S. (1973) Paleocene mollusks from Ewekoro, southern Nigeria. Malacologia 14:19-27, figs. 1-2, pls. 1-2. ADEGOKE, O.S. (1977) Stratigraphy and paleontology of the Ewekoro Formation (Paleocene) of southeastern Nigeria. Bulletins of American Paleontology 71(295):1-379, figs. 1-6, pls. 1-50. AIKEN, R. P. (2016) Description of two undescribed subspecies and one fossil species of the Genus Cypraeovula Gray, 1824 from South Africa. Beautifulcowries Magazine 8: 14-22 AIKEN, R., JOOSTE, P. & ELS, M. (2010) Cypraeovula capensis - A specie of Diversity and Beauty. Strandloper 287 p. 16 ff AIKEN, R., JOOSTE, P. & ELS, M. (2014) Cypraeovula capensis. A species of diversity and beauty. Beautifulcowries Magazine 5: 38–44 ALLAN, J. (1956) Cowry Shells of World Seas. Georgian House, Melbourne, Australia, 170 p., pls. 1-15. AMANO, K. (1992) Cypraea ohiroi and its associated molluscan species from the Miocene Kadonosawa Formation, northeast Japan. Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum 19:405-411, figs. 1-2, pl. 57. ANCEY, C.F. (1901) Cypraea citrina Gray. The Nautilus 15(7):83. ANONOMOUS. (1971) Malacological news. La Conchiglia 13(146-147):19-20, 5 unnumbered figs. ANONYMOUS. (1925) Index and errata. The Zoological Journal. 1: [593]-[603] January. ANONYMOUS. (1889) Cypraea venusta Sowb. The Nautilus 3(5):60. ANONYMOUS. (1893) Remarks on a new species of Cypraea. -

The Hawaiian Species of Conus (Mollusca: Gastropoda)1

The Hawaiian Species of Conus (Mollusca: Gastropoda) 1 ALAN J. KOHN2 IN THECOURSE OF a comparative ecological currents are factors which could plausibly study of gastropod mollus ks of the genus effect the isolation necessary for geographic Conus in Hawaii (Ko hn, 1959), some 2,400 speciation . specimens of 25 species were examined. Un Of the 33 species of Conus considered in certainty ofthe correct names to be applied to this paper to be valid constituents of the some of these species prompted the taxo Hawaiian fauna, about 20 occur in shallow nomic study reported here. Many workers water on marine benches and coral reefs and have contributed to the systematics of the in bays. Of these, only one species, C. ab genus Conus; nevertheless, both nomencla breviatusReeve, is considered to be endemic to torial and biological questions have persisted the Hawaiian archipelago . Less is known of concerning the correct names of a number of the species more characteristic of deeper water species that occur in the Hawaiian archi habitats. Some, known at present only from pelago, here considered to extend from Kure dredging? about the Hawaiian Islands, may (Ocean) Island (28.25° N. , 178.26° W.) to the in the future prove to occur elsewhere as island of Hawaii (20.00° N. , 155.30° W.). well, when adequate sampling methods are extended to other parts of the Indo-West FAUNAL AFFINITY Pacific region. As is characteristic of the marine fauna of ECOLOGY the Hawaiian Islands, the affinities of Conus are with the Indo-Pacific center of distribu Since the ecology of Conus has been dis tion . -

The Marine Zoologist, Volume 1, Number 7, 1959

The Marine Zoologist, Volume 1, Number 7, 1959 Item Type monograph Publisher Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales Download date 23/09/2021 18:13:28 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/32615 TI I LIBRAR THE MARINE ZOOLOGIST Vol 1. No.". Sydney, September 18, -1959 Donated by BAMFIELD MARINE STATION Dr. Ian McTaggart Cowan ~~THE some of the molluscs these were replaced as soon as the "danger" had MARINE ZOOLOGIST" passed. Owing to the darkness and depth of water it was difficult to make detailed observations of parental care. The mother used her siphon to Vol. 1. No.7. squirt water over the eggs, and her tentacles were usually weaving in and out among the egg-strings. The same thing was observed with the female in (Incorporated with the Proceedings of the Royal Zoological Society of April 1957, and Le Souef & Allan recorded the fact in some detail in New South Wales, 1957-58, published September 18, 1959.) 1933 and 1937. Unfortunately on 29th October 1957 the tank had to be emptied and cleaned and the octopus was released into the sea in a rather weak state. Her "nest" was destroyed and the eggs removed and examined. It came as a surprise to find that hatching had commenced and was progressing at a rapid rate because the eggs examined on 8th October showed little sign Some Observations on the Development of Two of development and it was believed that, as reported by Le Souef & Allan (1937), 5-6 weeks had to elapse between laying and hatching. -

Bab Iv Hasil Penelitian Dan Pembahasan

BAB IV HASIL PENELITIAN DAN PEMBAHASAN A. Hasil Penelitian dan Pembahasan Tahap 1 1. Kondisi Faktor Abiotik Ekosistem perairan dapat dipengaruhi oleh suatu kesatuan faktor lingkungan, yaitu biotik dan abiotik. Faktor abiotik merupakan faktor alam non-organisme yang mempengaruhi proses perkembangan dan pertumbuhan makhluk hidup. Dalam penelitian ini, dilakukan analisis faktor abiotik berupa faktor kimia dan fisika. Faktor kimia meliputi derajat keasaman (pH). Sedangkan faktor fisika meliputi suhu dan salinitas air laut. Hasil pengukuran suhu, salinitas, dan pH dapat dilihat sebagai tabel berikut: Tabel 4.1 Faktor Abiotik Pantai Peh Pulo Kabupaten Blitar Faktor Abiotik No. Letak Substrat Suhu Salinitas Ph P1 29,8 20 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir S1 1. P2 30,1 23 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir P3 30,5 28 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir 2. P1 29,7 38 8 Berbatu dan Berpasir S2 P2 29,7 40 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir P3 29,7 33 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir 3. P1 30,9 41 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir S3 P2 30,3 42 8 Berbatu dan Berpasir P3 30,1 41 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir 77 78 Tabel 4.2 Rentang Nilai Faktor Abiotik Pantai Peh Pulo Faktor Abiotik Nilai Suhu (˚C) 29,7-30,9 Salinitas (%) 20-42 Ph 7-8 Berdasarkan pengukuran faktor abiotik lingkungan, masing-masing stasiun pengambilan data memiliki nilai yang berbeda. Hal ini juga mempengaruhi kehidupan gastropoda yang ditemukan. Kehidupan gastropoda sangat dipengaruhi oleh besarnya nilai suhu. Suhu normal untuk kehidupan gastropoda adalah 26-32˚C.80 Sedangkan menurut Sutikno, suhu sangat mempengaruhi proses metabolisme suatu organisme, gastropoda dapat melakukan proses metabolisme optimal pada kisaran suhu antara 25- 32˚C. -

(Approx) Mixed Micro Shells (22G Bags) Philippines € 10,00 £8,64 $11,69 Each 22G Bag Provides Hours of Fun; Some Interesting Foraminifera Also Included

Special Price £ US$ Family Genus, species Country Quality Size Remarks w/o Photo Date added Category characteristic (€) (approx) (approx) Mixed micro shells (22g bags) Philippines € 10,00 £8,64 $11,69 Each 22g bag provides hours of fun; some interesting Foraminifera also included. 17/06/21 Mixed micro shells Ischnochitonidae Callistochiton pulchrior Panama F+++ 89mm € 1,80 £1,55 $2,10 21/12/16 Polyplacophora Ischnochitonidae Chaetopleura lurida Panama F+++ 2022mm € 3,00 £2,59 $3,51 Hairy girdles, beautifully preserved. Web 24/12/16 Polyplacophora Ischnochitonidae Ischnochiton textilis South Africa F+++ 30mm+ € 4,00 £3,45 $4,68 30/04/21 Polyplacophora Ischnochitonidae Ischnochiton textilis South Africa F+++ 27.9mm € 2,80 £2,42 $3,27 30/04/21 Polyplacophora Ischnochitonidae Stenoplax limaciformis Panama F+++ 16mm+ € 6,50 £5,61 $7,60 Uncommon. 24/12/16 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Acanthopleura gemmata Philippines F+++ 25mm+ € 2,50 £2,16 $2,92 Hairy margins, beautifully preserved. 04/08/17 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Acanthopleura gemmata Australia F+++ 25mm+ € 2,60 £2,25 $3,04 02/06/18 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Acanthopleura granulata Panama F+++ 41mm+ € 4,00 £3,45 $4,68 West Indian 'fuzzy' chiton. Web 24/12/16 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Acanthopleura granulata Panama F+++ 32mm+ € 3,00 £2,59 $3,51 West Indian 'fuzzy' chiton. 24/12/16 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Chiton tuberculatus Panama F+++ 44mm+ € 5,00 £4,32 $5,85 Caribbean. 24/12/16 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Chiton tuberculatus Panama F++ 35mm € 2,50 £2,16 $2,92 Caribbean. 24/12/16 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Chiton tuberculatus Panama F+++ 29mm+ € 3,00 £2,59 $3,51 Caribbean. -

Systematics and Paleoenvironment of Quaternary Corals and Ostracods in Dallol Carbonates, North Afar

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF EARTH SCIENCES SYSTEMATICS AND PALEOENVIRONMENT OF QUATERNARY CORALS AND OSTRACODS IN DALLOL CARBONATES, NORTH AFAR ADDIS HAILU ENDESHAW NOV., 2017 ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA i Systematics and Paleoenvironments of Quaternary Corals and Ostracods in Dallol Carbonates; North Afar Addis Hailu Endeshaw Advisor – Dr. Balemwal Atnafu A Thesis Submitted to School of Earth Sciences Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science in Earth Sciences (Paleontology and Paleoenvironment) Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Nov., 2017 ii iii ABSTRACT Systematics and Paleoenvironment of Quaternary Corals and Ostracods in Dallol Carbonates, North Afar Addis Hailu Endeshaw Addis Ababa University, 2017 There are reef structures developed in Dallol during the Quaternary Period as a result of flooding of the area by the Red Sea at least two times. Dallol area is situated in the northern most part of the Eastern African Rift system. The studied coral outcrops are aligned along the northwestern margin of the Afar rift. This research focused on the investigation of systematics of corals and associated fossils of mollusca, echinoidea, ostracoda and foraminifera together with the reconstruction of past environmental conditions. Different scientific methods were followed in order to achieve the objectives of the study. These are detailed insitu morphological descriptions; field observations and measurements; laboratory preparations and microscopic examinations; comparison of the described specimens with type specimens; and paleoecological calculations using PAST-3 software. Total of 164 fossil and 9 sediment samples are collected from the field and examined. The Dallol corals are classified into 12 Families, 29 Genera and 60 Species. -

Biogeography of Coral Reef Shore Gastropods in the Philippines

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274311543 Biogeography of Coral Reef Shore Gastropods in the Philippines Thesis · April 2004 CITATIONS READS 0 100 1 author: Benjamin Vallejo University of the Philippines Diliman 28 PUBLICATIONS 88 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: History of Philippine Science in the colonial period View project Available from: Benjamin Vallejo Retrieved on: 10 November 2016 Biogeography of Coral Reef Shore Gastropods in the Philippines Thesis submitted by Benjamin VALLEJO, JR, B.Sc (UPV, Philippines), M.Sc. (UPD, Philippines) in September 2003 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Marine Biology within the School of Marine Biology and Aquaculture James Cook University ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to describe the distribution of coral reef and shore gastropods in the Philippines, using the species rich taxa, Nerita, Clypeomorus, Muricidae, Littorinidae, Conus and Oliva. These taxa represent the major gastropod groups in the intertidal and shallow water ecosystems of the Philippines. This distribution is described with reference to the McManus (1985) basin isolation hypothesis of species diversity in Southeast Asia. I examine species-area relationships, range sizes and shapes, major ecological factors that may affect these relationships and ranges, and a phylogeny of one taxon. Range shape and orientation is largely determined by geography. Large ranges are typical of mid-intertidal herbivorous species. Triangualar shaped or narrow ranges are typical of carnivorous taxa. Narrow, overlapping distributions are more common in the central Philippines. The frequency of range sizesin the Philippines has the right skew typical of tropical high diversity systems. -

Training Workshop on the Taxonomy of Marine Molluscs Mauritius, October 2017

Training workshop on the taxonomy of marine molluscs Mauritius, October 2017 Introduction IOC Biodiversity and MOI organized a regional workshop in Mauritius in October 2017 for 4 days. The main objective of the workshop were (i) to train regional marine biologists to the taxonomy of molluscs, (ii) to build capacities in the description and identification of molluscs, (iii) to assess the mollusc biodiversity and its evolution in tropical marine ecosystems. Figure 1: Le Bouchon sampling site Material and Methods About 20 participants attended the workshop with about half of them from Mauritius and the others from Madagascar, Comoros, Kenya and Tanzania. The workshop was led by an Australian expert. The workshop followed these 3 steps: - Day 1: Formal classroom training about taxonomy, molluscs and shells features. Generals information slide about molluscs were projected. - Day 2: Field sampling in Mauritius at Le Bouchon (South-east coast). The sampling was performed in various biotopes provided at the location: beach, rocky shore, mangrove and lagoon. Lagoon itself provided various environments (live coral, rubbles, sand, grass, silt). Some samplers were on foot and other snorkelling. The only method used was hand picking of shells during one hour. Shells were either dead (empty or crabbed) or alive with limitation of 1 specimen per species. The objective of the sampling was not quantitative but qualitative. The shells have been washed and put to dry in the lab after the field collection. - Day 3-4: Analysis of the samples sorted and numbered by kind and appearance. Participants had to write a description of as many species as they could in group of 2-3. -

Archeology in the Chesapeake Region Saturday, February 6, 2016 – 9:00 AM ‐3:30 PM at Gunston Hall, 10709 Gunston Road, Mason Neck, VA 22079

January 2016 Please join the Friends of Fairfax County Archaeology and Cultural Resources, Gunston Hall Plantation, and the Cultural Resource Management and Protection Branch of the Fairfax County Park Authority in hosting an archaeological symposium. History beneath our Feet: Archeology in the Chesapeake Region Saturday, February 6, 2016 – 9:00 AM ‐3:30 PM At Gunston Hall, 10709 Gunston Road, Mason Neck, VA 22079 Barbara Heath they can be usefully interpreted as artifacts of global, and local systems of Indo‐Pacific Cowrie Shells: Global Trade trade. and Local Exchange in Colonial Virginia Many archaeologists Barbara Heath is an associate professor of have interpreted Anthropology who specializes in the cowrie shells found archaeology of colonialism and the on sites from the African Diaspora, with a focus on the Northeast to the Chesapeake and the Caribbean. Prior to Caribbean as joining the faculty of the University of evidence of material Tennessee, Knoxville in 2006, Dr. Heath expressions of worked for more than 20 years as an African or African archaeologist at historic houses and American ethnicity or museums in Virginia, including Colonial spirituality. However, understanding the Williamsburg, Monticello, and Thomas routes by which these non‐native shells Jefferson’s Poplar Forest. made their way to the New World, and their distribution and use over time and Heath has authored Hidden Lives, The space, shows that they were global Archaeology of Slave Life at Thomas commodities with localized meanings. Jefferson’s Poplar Forest and, with Jack Gary, edited Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, Barbara Heath will present historical and Unearthing a Virginia Plantation. She is archaeological evidence relating to the currently working on Material Worlds: movement and modification of these Archaeology, Consumption, and the Road shells from harvest to delivery. -

THE LISTING of PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T

August 2017 Guido T. Poppe A LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS - V1.00 THE LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T. Poppe INTRODUCTION The publication of Philippine Marine Mollusks, Volumes 1 to 4 has been a revelation to the conchological community. Apart from being the delight of collectors, the PMM started a new way of layout and publishing - followed today by many authors. Internet technology has allowed more than 50 experts worldwide to work on the collection that forms the base of the 4 PMM books. This expertise, together with modern means of identification has allowed a quality in determinations which is unique in books covering a geographical area. Our Volume 1 was published only 9 years ago: in 2008. Since that time “a lot” has changed. Finally, after almost two decades, the digital world has been embraced by the scientific community, and a new generation of young scientists appeared, well acquainted with text processors, internet communication and digital photographic skills. Museums all over the planet start putting the holotypes online – a still ongoing process – which saves taxonomists from huge confusion and “guessing” about how animals look like. Initiatives as Biodiversity Heritage Library made accessible huge libraries to many thousands of biologists who, without that, were not able to publish properly. The process of all these technological revolutions is ongoing and improves taxonomy and nomenclature in a way which is unprecedented. All this caused an acceleration in the nomenclatural field: both in quantity and in quality of expertise and fieldwork. The above changes are not without huge problematics. Many studies are carried out on the wide diversity of these problems and even books are written on the subject. -

CONE SHELLS - CONIDAE MNHN Koumac 2018

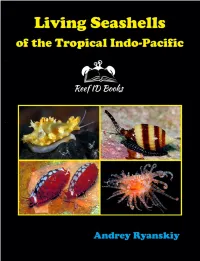

Living Seashells of the Tropical Indo-Pacific Photographic guide with 1500+ species covered Andrey Ryanskiy INTRODUCTION, COPYRIGHT, ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION Seashell or sea shells are the hard exoskeleton of mollusks such as snails, clams, chitons. For most people, acquaintance with mollusks began with empty shells. These shells often delight the eye with a variety of shapes and colors. Conchology studies the mollusk shells and this science dates back to the 17th century. However, modern science - malacology is the study of mollusks as whole organisms. Today more and more people are interacting with ocean - divers, snorkelers, beach goers - all of them often find in the seas not empty shells, but live mollusks - living shells, whose appearance is significantly different from museum specimens. This book serves as a tool for identifying such animals. The book covers the region from the Red Sea to Hawaii, Marshall Islands and Guam. Inside the book: • Photographs of 1500+ species, including one hundred cowries (Cypraeidae) and more than one hundred twenty allied cowries (Ovulidae) of the region; • Live photo of hundreds of species have never before appeared in field guides or popular books; • Convenient pictorial guide at the beginning and index at the end of the book ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The significant part of photographs in this book were made by Jeanette Johnson and Scott Johnson during the decades of diving and exploring the beautiful reefs of Indo-Pacific from Indonesia and Philippines to Hawaii and Solomons. They provided to readers not only the great photos but also in-depth knowledge of the fascinating world of living seashells. Sincere thanks to Philippe Bouchet, National Museum of Natural History (Paris), for inviting the author to participate in the La Planete Revisitee expedition program and permission to use some of the NMNH photos.