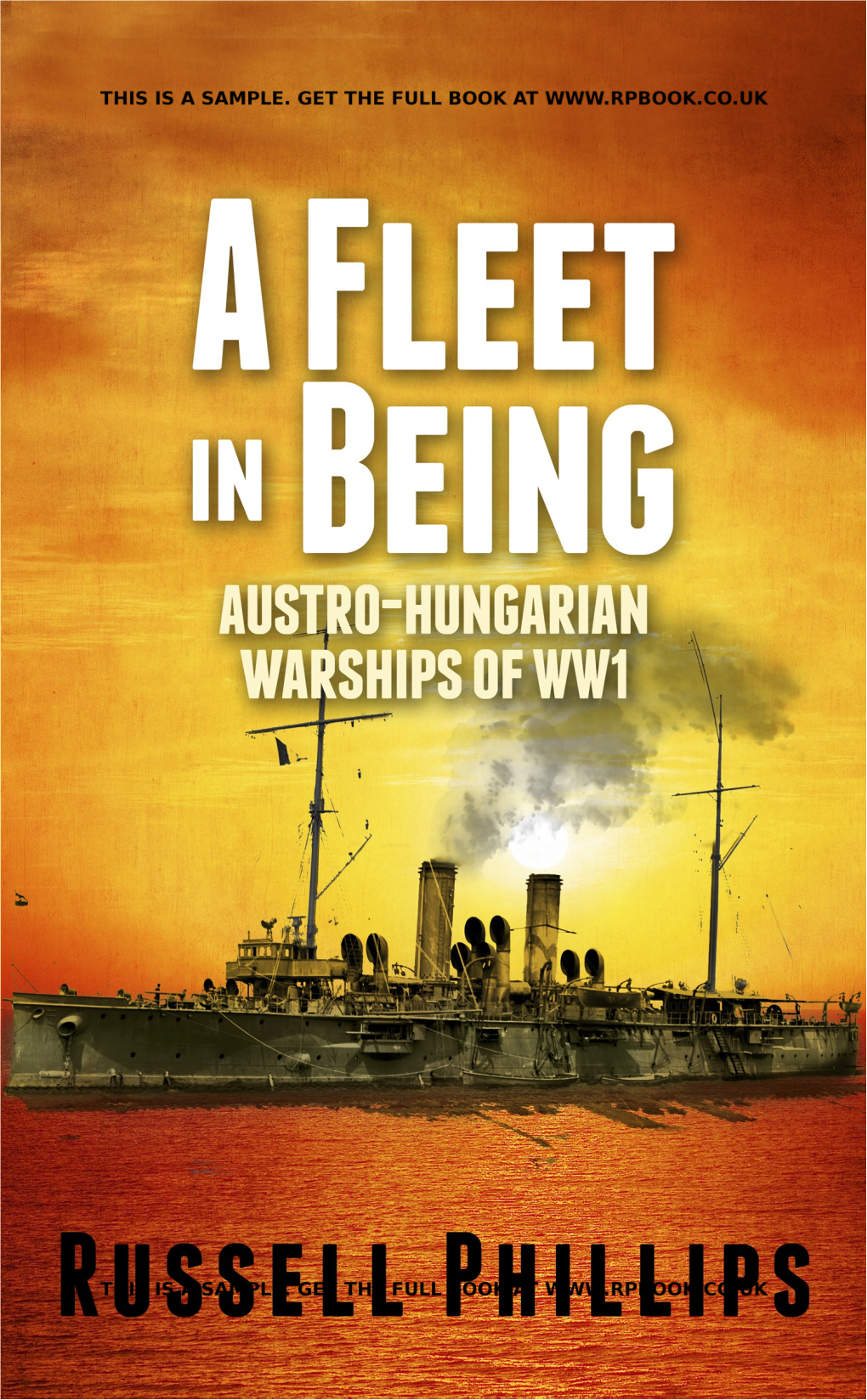

A Fleet in Being: Austro-Hungarian Warships of WWI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Am Descending Into the Depths, Something I Have Done So Many Times Before

I am descending into the depths, something I have done so many times before. As always I am repeating the same actions, with the same attention and coolness; but I also realise that my desire to see the wreck is something more, almost a hunger. The water is so clear that suddenly, on the edge of my vision I think I can see the bottom, but I know that it is too soon, too shallow. I realise that it is not the seabed below as I start to discern two enormous, powerful propellers. One of them is completely wrapped by a trawl net that passes over the rudder and disappears into the depths. I start to see the other propeller and the gigantic hull of the wreck, so big that I mistake it for the bottom. I know for certain that I, and the rest of the team following me down the shot-line will soon be exploring the final resting place of the Szent Istvan. To me the Szent Istvan is more than a wreck; she is a magnet, a piece of history that has drawn a few explorers to her. Her story has come to symbolise the tumultuous events of the last year of the Great War and the lives of the men involved in her story: Admiral Miklos Horthy de Nagybanya, Commander in Chief of the Imperial Royal Austro-Hungarian Navy, and Lieutenant Commander Luigi Rizzo, Commander of the IV squadron of the Royal Italian Navy. The wreck stretches away from me. Directly ahead is one of the propellers, I can't exactly make out its dimensions, it soars over me. -

The Semaphore Circular No 661 the Beating Heart of the RNA July 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 661 The Beating Heart of the RNA July 2016 The No 3 Area Ladies getting the Friday night raffle ready at Conference! This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. Conference 2016 report 2. Remembrance Parade 13 November 2016 3. Slops/Merchandise & Membership 4. Guess Where? 5. Donations 6. Pussers Black Tot Day 7. Birds and Bees Joke 8. SAIL 9. RN VC Series – Seaman Jack Cornwell 10. RNRMC Charity Banquet 11. Mini Cruise 12. Finance Corner 13. HMS Hampshire 14. Joke Time 15. HMS St Albans Deployment 16. Paintings for Pleasure not Profit 17. Book – Wren Jane Beacon 18. Aussie Humour 19. Book Reviews 20. For Sale – Officers Sword Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General Secretary DGS Deputy General Secretary AGS Assistant General Secretary CONA Conference of Naval Associations IMC International Maritime Confederation NSM Naval Service Memorial Throughout indicates a new or substantially changed entry 2 Contacts Financial Controller 023 9272 3823 [email protected] FAX 023 9272 3371 Deputy General Secretary 023 9272 0782 [email protected] Assistant General Secretary (Membership & Slops) 023 9272 3747 [email protected] S&O Administrator 023 9272 0782 [email protected] General Secretary 023 9272 2983 [email protected] Admin 023 92 72 3747 [email protected] Find Semaphore Circular On-line ; http://www.royal-naval-association.co.uk/members/downloads or.. -

United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922

Cover: During World War I, convoys carried almost two million men to Europe. In this 1920 oil painting “A Fast Convoy” by Burnell Poole, the destroyer USS Allen (DD-66) is shown escorting USS Leviathan (SP-1326). Throughout the course of the war, Leviathan transported more than 98,000 troops. Naval History and Heritage Command 1 United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922 Frank A. Blazich Jr., PhD Naval History and Heritage Command Introduction This document is intended to provide readers with a chronological progression of the activities of the United States Navy and its involvement with World War I as an outside observer, active participant, and victor engaged in the war’s lingering effects in the postwar period. The document is not a comprehensive timeline of every action, policy decision, or ship movement. What is provided is a glimpse into how the 20th century’s first global conflict influenced the Navy and its evolution throughout the conflict and the immediate aftermath. The source base is predominately composed of the published records of the Navy and the primary materials gathered under the supervision of Captain Dudley Knox in the Historical Section in the Office of Naval Records and Library. A thorough chronology remains to be written on the Navy’s actions in regard to World War I. The nationality of all vessels, unless otherwise listed, is the United States. All errors and omissions are solely those of the author. Table of Contents 1914..................................................................................................................................................1 -

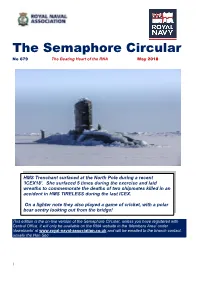

The Semaphore Circular No 679 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2018

The Semaphore Circular No 679 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2018 HMS Trenchant surfaced at the North Pole during a recent ‘ICEX18’. She surfaced 5 times during the exercise and laid wreaths to commemorate the deaths of two shipmates killed in an accident in HMS TIRELESS during the last ICEX. On a lighter note they also played a game of cricket, with a polar bear sentry looking out from the bridge! This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec 1 Daily Orders (follow each link) Orders [follow each link] 1. 2018 Dublin Conference 2. Finance Corner 3. RNVC Surgeon William Job Maillard VC 4. Joke – Golfing 5. Charity Donations 6. Guess Where 7. Branch and Recruitment and Retention Advisor 8. Conference 2019 – Wyboston Lakes 9. Veterans Gateway and Preserved Pensions 10. Assistance Request Please 11. HMS Gurkha Assistance 12. Can you Assist – HMS Arethusa 13. RNAS Yeovilton Air Day 14. HMS Collingwood Open Day 15. HMS Bristol EGM 16. Association of Wrens NSM Visit 17. Pembroke House Annual Garden Party 18. Joke – Small Cricket Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General Secretary DGS Deputy -

TIE Corps Pilot Manual, Emperor's Hammer Training Manual, Etc.)

1 2 Table of Contents I. Introduction II. Chain of Command III. Structure IV. Positions a. Line Positions Trainee (TRN) Flight Member (FM) Flight Leader (FL) Squadron Commander (CMDR) Wing Commander (WC) b. Flag Positions Commodore (COM) c. TIE Corps Command Staff Combat Operations Officer (COO/TC-3) Strategic Operations Officer (SOO/TC-2) TIE Corps Commander (TCCOM/TC-1) d. Assistants and Other Secondary Positions Squadron Executive Officer (SQXO) Warden of the Imperial Archives (WARD) Editor of the TC Newsletter (EDR) Simulations Officer (SIMS) Captain of the M/FRG Phoenix (CAPT) e. Tour of Duty f. Reserves V. Ranks a. Line Ranks b. Flag Ranks VI. Promotions a. Promotional Authority b. Position Requirements c. Rank requirements d. Promotion to LT e. TIE Corps Core VII. Medals a. Merit Awards Medal of Honor (MoH) Imperial Cross (IC) 3 Order of the Renegade (OoR) Grand Order of the Emperor (GOE) Gold Star of the Empire (GS) Silver Star of the Empire (SS) Bronze Star of the Empire (BS) Palpatine Crescent (PC) Imperial Security Medal (ISM) Imperial Achievement Ribbon (IAR) b. Service Medals Medal of Instruction (MoI) Medal of Tactics (MoT) Medal of Communication (MoC) TIE Corps Commander’s Unit Award (TUA) TIE Corps Meritorious Unit Award (MUA) Iron Star (IS) Legion of Combat (LoC) Legion of Skirmish (LoS) Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) Order of the Vanguard (OV) c. Commendations Commendation of Bravery (CoB) Commendation of Excellence (CoE) Commendation of Loyalty (CoL) Commendation of Service (CoS) Letter of Achievement (LoA) VIII. Procedures a. Appointments b. Transfers c. Promotions and Awards d. Creating Competitions e. -

Conrad Von Hötzendorf and the “Smoking Gun”: a Biographical Examination of Responsibility and Traditions of Violence Against Civilians in the Habsburg Army 55

1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. (Guest Editor) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 23 uno press innsbruck university press Copyright © 2014 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Allison Reu Cover photo: “In enemy position on the Piave levy” (Italy), June 18, 1918 WK1/ALB079/23142, Photo Kriegsvermessung 5, K.u.k. Kriegspressequartier, Lichtbildstelle Vienna Cover photo used with permission from the Austrian National Library – Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Vienna Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608010264 ISBN: 9783902936356 uno press Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Markus Habermann -

University of Rijeka - Faculty of Maritime Studies

UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA - FACULTY OF MARITIME STUDIES UNDERGRADUATE AND GRADUATE ACADEMIC PROGRAM LOGISTICS AND MANAGEMENT IN MARITIME AFFAIRS AND TRANSPORT RIJEKA, 2014 MAIN DATA AND ORGANIZATION OF THE FACULTY MANAGEMENT OF THE FACULTY Dean: Professor Ser ño Kos, Ph.D., FRIN Vice-Dean for Academic Affairs Assistant professor Igor Rudan, Ph.D. Vice-Dean for Business Relations and Finance: Assistant professor, Alen Jugovi ć Ph.D. Vice-Dean for Vocational Training and Development: Assistant professor Dragan Martinovi ć, Ph.D. Vice-Dean for Scientific and Research Activities: Associate professor Boris Svili čić, Ph.D. Secretary: Željko Ševerdija, L.L.B. INTERNAL ORGANIZATION Department of Marine Engineering and Power Supply Systems • Headed by: Professor Ivica Šegulja, Ph.D. Department of Marine Electronic Engineering, Automatic Theory and Information Technology • Headed by: Associated professor Nikola Tomac, Ph.D. Department of Logistics and Management in Maritime Affairs and Transport • Headed by: Professor Dragan Čiši ć, Ph.D. Department of Nautical Sciences and Maritime Transport Technology • Headed by: Associated professor Robert Mohovi ć, Ph.D. Department of Technology and Organization in Maritime Affairs and Transport • Headed by: Professor Čedomir Dundovi ć, Ph.D. Department of Social Sciences • Headed by: Assistant professor Biserka Rukavina, Ph.D. Department of Natural Sciences • Headed by: Assistant professor Biserka Draš čić Ban Department of Foreign Languages • Headed by: Jadranka Valenti ć, M.A. ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF Dean's Office -

A Collection of Stories and Memories by Members of the United States Naval Academy Class of 1963

A Collection of Stories and Memories by Members of the United States Naval Academy Class of 1963 Compiled and Edited by Stephen Coester '63 Dedicated to the Twenty-Eight Classmates Who Died in the Line of Duty ............ 3 Vietnam Stories ...................................................................................................... 4 SHOT DOWN OVER NORTH VIETNAM by Jon Harris ......................................... 4 THE VOLUNTEER by Ray Heins ......................................................................... 5 Air Raid in the Tonkin Gulf by Ray Heins ......................................................... 16 Lost over Vietnam by Dick Jones ......................................................................... 23 Through the Looking Glass by Dave Moore ........................................................ 27 Service In The Field Artillery by Steve Jacoby ..................................................... 32 A Vietnam story from Peter Quinton .................................................................... 64 Mike Cronin, Exemplary Graduate by Dick Nelson '64 ........................................ 66 SUNK by Ray Heins ............................................................................................. 72 TRIDENTS in the Vietnam War by A. Scott Wilson ............................................. 76 Tale of Cubi Point and Olongapo City by Dick Jones ........................................ 102 Ken Sanger's Rescue by Ken Sanger ................................................................ 106 -

KAISERIN UND KÖNIGIN MARIA THERESIA and the Crown- Princess Stayed on Board

AUSTRO-HUNGARIAN BATTLESHIPS The following list contains all Austro-Hungarian battleships which were in commission dur- ing the Great War. (Compiled by András Veperdi) ABBREVIATIONS Arsenal: Naval Shipyard, Pola Arsenal Lloyd: Austrian Lloyd Shipyard, Trieste CNT: Naval Docks Trieste, Monfalcone CNT Pola: In the year of 1916 the CNT was evacuated from Monfalcone to Pola, where the submarine building was continued. Da Bud: Ganz and Danubius AG, Budapest (formerly: H. Schönichen Shipyard) Da Fi: Ganz and Danubius Shipyard, Bergudi, Fiume Da PR: Ganz and Danubius Shipyard, Porto Ré (today: Krajlevica in Croatia) Lussinpiccolo: Marco U. Martinolich, Lussinpiccolo (today: Mali Losinj in Croatia) STT: Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, Trieste (Its name was Austria – Werft between the years of 1916 and 1918.) aa: anti-aircraft ihp: indicated horse power nm: nautical mile AC: alternating current IP: Intermediate Pressure oa: over all atm: atmosphere K: Austrian Crown pp: between perpendicular bhp: brake horse power kg: kilogram qf: quick firing (gun) cal: calibre km: kilometre Rpg: Rounds per guns’ barrels cl: class kts: knots rpm: revolution per minute cm: centimetre L: Barrel length in calibre sec: second constr: constructional LP: Low Pressure shp: Shaft horse power DC: direct current m: metre t: tonne(s) (metric tonne(s)) HP: High Pressure mm: millimetre wl: water line 1 SMS KRONPRINZ ERZHERZOG RUDOLF – Local Defence Ship SMS Kronprinz Erzherzog Rudolf The after 30.5 cm gun of SMS Kronprinz Erzherzog Rudolf Laid down : Launched : Commissioned : 25/01/1884 06/07/1887 20/09/1889 Later name: KUMBOR Builder: Arsenal - Pola Costs: 10,885,140 K Sister ship: She had not. -

P. Lucchi Pola E Viribus Unitis

1 LA PIAZZAFORTE DI POLA E L’AFFONDAMENTO DEL VIRIBUS UNITIS. Patrizia Lucchi Vedaldi 1) PREMESSA. 2) DAL 26 OTTOBRE AL 1° NOVEMBRE. 3) ANCORA SULL’AFFONDAMENTO DEL VIRIBUS UNITIS. 4) L’OCCUPAZIONE DELLA PIAZZAFORTE IN NOME DEGLI ALLEATI. 1) PREMESSA. Affrontando la genesi e l’esecuzione dell’impresa di Pola del 1° novembre 1918, credo sia necessario sfatare una leggenda creata dai detrattori degli italiani e che ancora oggi ogni tanto viene riproposta1, con la quale si è tentato di far credere che l’affondamento del Viribus Unitis fosse avvenuto quando già l’Italia sapeva che la flotta imperiale era stata consegnata, per accordo, al nascente Stato degli Sloveni, Croati e Serbi. Ques’ultimo, peraltro, in gran segreto, stava tradendo quanto pattuito con il Regno dei Serbi a Corfù il 20 luglio 1917. Preciso che nessuno degli autori da me consultati riporta tutti i fatti che sto per presentare. Pertanto ho cercato di ricomporre gli eventi, intersecando vari studi e documenti. Ne è emerso un quadro interessante, grazie anche a una fonte inedita: i fogli di servizio (Hautptgrundbuchsblatt) di 27 marinai di Neresine, sull’ isola di Lussino, che vennero “liquidati” (zuerkannt) già il 27 ottobre. Se ci rifacciamo alle date, innanzi tutto rilevo che data solo 28 ottobre la comunicazione ufficiale con la quale si portava a conoscenza degli equipaggi il fatto che si intendeva concedere licenze illimitate a chi ne 1 Jane Hathaway, Rebellion, Repression, Reinvention, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, p. 205; Achille Rastelli, L’affondamento della SMS VIRIBUS UNITIS, Quaderni, vol. XVIII, Centro di Ricerche Storiche di Rovigno, 2007. -

Otto Schniewind Testimony University of North Dakota

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Nuremberg Transcripts Collections 5-25-1948 High Command Case: Otto Schniewind Testimony University of North Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/nuremburg-transcripts Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation University of North Dakota, "High Command Case: Otto Schniewind Testimony" (1948). Nuremberg Transcripts. 16. https://commons.und.edu/nuremburg-transcripts/16 This Court Document is brought to you for free and open access by the Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Collections at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nuremberg Transcripts by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 25 May–A–MW–17–2–Gallagher (Int.Evand) COURT V, CASE XII THE PRESIDENT: You may have the same privileges and rights with respect to the documents that have been heretofore indicated. DR. FRITSCH: I merely have one request, Your Honor. In my opening statement I made a motion to strike Counts I and IV of the Indictment. I would now like to ask the Tribunal to rule on this motion. THE PRESIDENT: If you desire a ruling on that motion at this time, inasmuch as the testimony is now in,the [sic] motion will be overruled, because that is one of the essential questions that will have to be determined when the opinion is written. If there is no proof of these, why, of course, then those Counts have not been substantiated, but at this time the motion will be overruled. -

Admiral Nicholas Horthy: MEMOIRS

Admiral Nicholas Horthy: MEMOIRS Annotated by Andrew L. Simon Copyright © 2000 Andrew L. Simon Original manuscript copyright © 1957, Ilona Bowden Library of Congress Card Number: 00-101186 Copyright under International Copyright Union All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval devices or systems, without prior written permission from the publisher. ISBN 0-9665734-9 Printed by Lightning Print, Inc. La Vergne , TN 37086 Published by Simon Publications, P.O. Box 321, Safety Harbor, FL 34695 Admiral Horthy at age 75. Publication record of Horthy’s memoirs : • First Hungarian Edition: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1953. • German Edition: Munich, Germany, 1953. • Spanish Edition: AHR - Barcelona, Spain, 1955. • Finnish Edition: Otava, Helsinki, Finland, 1955. • Italian Edition, Corso, Rome, Italy, 1956. • U. S. Edition: Robert Speller & Sons, Publishers, New York, NY, 1957. • British Edition: Hutchinson, London, 1957. • Second Hungarian Edition: Toronto, Canada: Vörösváry Publ., 1974. • Third Hungarian Edition: Budapest, Hungary:Europa Historia, 1993. Table of Contents FOREWORD 1 INTRODUCTION 5 PREFACE 9 1. Out into the World 11 2. New Appointments 33 3. Aide-de-Camp to Emperor Francis Joseph I at the Court of Vienna 1909-1914 49 4. Archduke Francis Ferdinand 69 5. Naval Warfare in the Adriatic. The Coronation of King Charles IV 79 6. The Naval Battle of Otranto 93 7. Appointment as Commander of the Fleet. The End 101 8. Revolution in Hungary: from Michael Károlyi to Béla Kun 109 9. Counter-Revolution. I am Appointed Minister of War And Commander-in-Chief 117 10.