Introducing Measurements in the Laboratory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science Safety

2010 Mississippi Science Framework Science Safety The guides that are cited below were developed by the Council of State Science Supervisors (CSSS) with support from the Eisenhower National Clearinghouse for Mathematics and Science Education, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Dupont Corporation, Intel Corporation, Americal Chemical Society, and the National Institutes of Health. Science Safety Booklets may be printed for use by educators. • Science Safety Booklets • Science and Safety: It's Elementary (PDF) - A Elementary Safety Guide • Science and Safety, Making the Connection (PDF) - A Secondary Safety Guide . Approved July 25, 2008 1 2010 Mississippi Science Framework A SUGGESTED PATTERN FOR CHEMICAL STORAGE The alphabetical method for storing chemicals presents hazards because chemicals, which can react violently with each other, may be stored in close proximity. Schools may wish to devise a simple color-coding scheme to address this problem. The code shown below, reproduced with permission from School Science Laboratories-A Guide to Some Hazardous Substances by the Council of State Science Supervisors, includes both solid and striped colors which are used to designate specific hazards as follows: Red - Flammability hazard: Store in a flammable chemical storage area. Red Stripe - Flammability hazard: Do not store in the same area as other flammable substances. Yellow - Reactivity hazard: Store separately from other chemicals. Yellow Stripe - Reactivity hazard: Do not store with other yellow coded chemicals; store separately. White - Contact hazard: Store separately in a corrosion-proof container. White Stripe - Contact hazard: Not compatible with chemicals in solid white category. Blue - Health hazard: Store in a secure poison area. Orange - Not suitably characterized by any of the foregoing categories. -

Construction of a Capillary Viscometer and the Study of Non-Newtonian Liquids" (1965)

Scholars' Mine Masters Theses Student Theses and Dissertations 1965 Construction of a capillary viscometer and the study of non- Newtonian liquids Hsun Kuang Yang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses Part of the Chemical Engineering Commons Department: Recommended Citation Yang, Hsun Kuang, "Construction of a capillary viscometer and the study of non-Newtonian liquids" (1965). Masters Theses. 7238. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses/7238 This thesis is brought to you by Scholars' Mine, a service of the Missouri S&T Library and Learning Resources. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ... ··f • CONSTRUCTION OF A CAPILLARY VISCOMETER -'"' '. ·~ i : AND THE STUDY OF NON-NEWTONIAN LIQUIDS BY HSUN KUANG YANG I fl ;/() 1\?: f A THESIS submitted to the faculty of the UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI AT ROLLA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN CHEMICAL ENGINEERING Rolla, Missouri 1965 Approved by (advisor) ii ABSTRACT A capillary tube viscometer was built for the purpose of investigating the fluid properties of non-Newtonian aqueous CMC and Carbopol solutions. The viscometer was tested with Newtonian liquids (glycerine, water and two different oils) having known viscosities to insure that the viscometer was operating correctly. The shear stress-shear rate data obtained for different concen trations of CMC and Carbopol solutions were correlated using the simple power law model. The power law constants were only slightly affected by saturating the solution with iodine and carbon tetrachloride. -

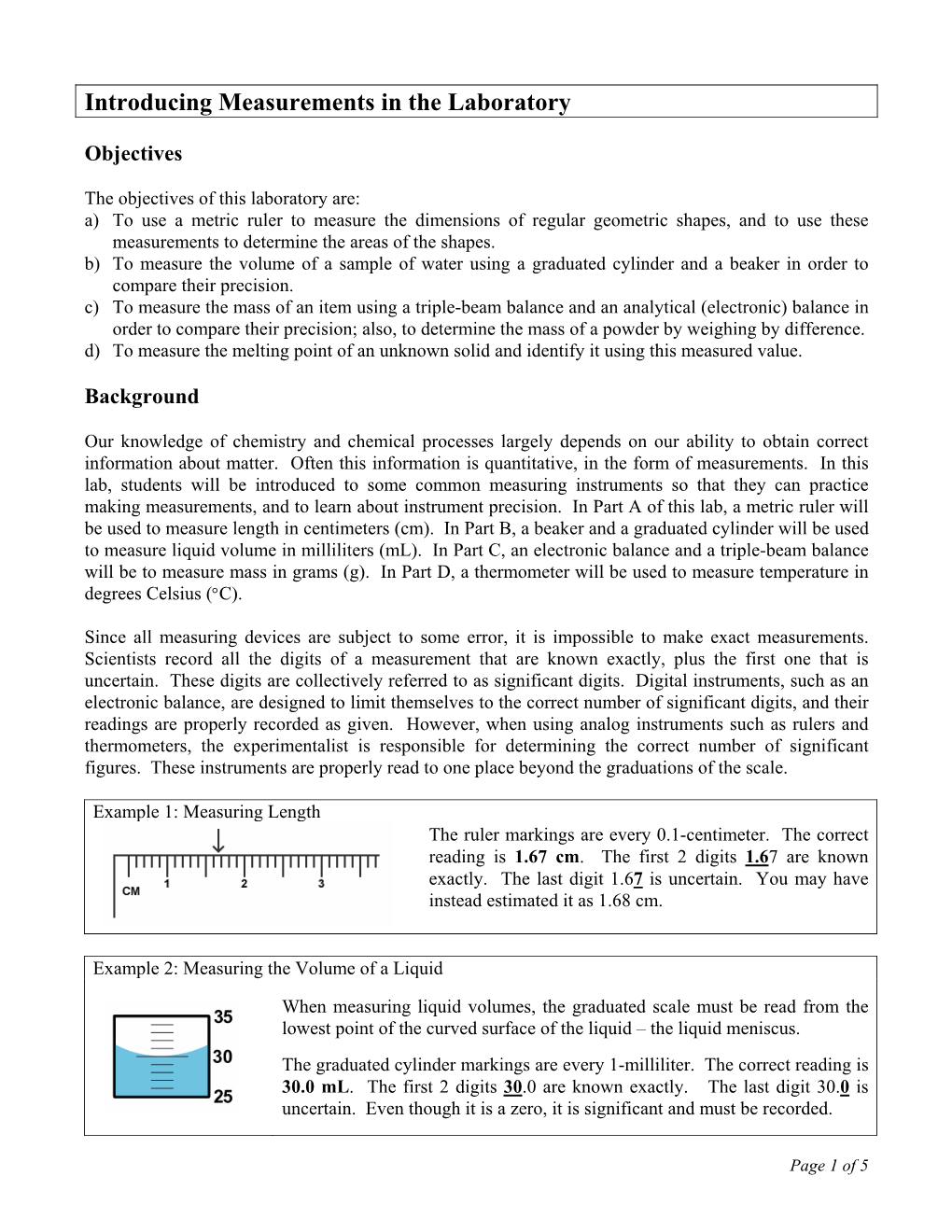

Process Skills Review Warm-Up C

Process Skills Review Warm-Up C. • Define function • Match the following 1. Puts out fire 2. Curved line of liquid in a graduated cylinder 3. Used to observe insects A. B. Which of the following describes the correct way to handle chemicals in a laboratory? A. It is safe to combine unknown chemicals as long as only small amounts are used. B. Return all chemicals to their original containers. C. Always pour extra amounts of the chemicals called for the experiment. D. To test for odors, always use a wafting motion. Which of the following describes the correct way to handle chemicals in a laboratory? A. It is safe to combine unknown chemicals as long as only small amounts are used. B. Return all chemicals to their original containers. C. Always pour extra amounts of the chemicals called for the experiment. D. To test for odors, always use a wafting motion. What task is being performed in the picture? A. measuring mass with a graduated cylinder B. measuring length with a triple beam balance C. measuring mass with a triple beam balance D. measuring length with a metric ruler What task is being performed in the picture? A. measuring mass with a graduated cylinder B. measuring length with a triple beam balance C. measuring mass with a triple beam balance D. measuring length with a metric ruler John and Lisa are conducting an experiment in their 7th grade science class in which they are handling potentially dangerous chemicals. As John is pouring a chemical from a beaker to a graduated cylinder, he splashes some of the chemical into his eyes. -

Drying Characteristics of Buna-S Rubber; Vacuum Shelf Drying, Rotary

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1949 Drying characteristics of Buna-S rubber; Vacuum shelf drying, rotary vacuum drying, cabinet air drying, and through-circulation air drying Wilson Ross Barnes Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Chemical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Barnes, Wilson Ross, "Drying characteristics of Buna-S rubber; Vacuum shelf drying, rotary vacuum drying, cabinet air drying, and through-circulation air drying " (1949). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 13520. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/13520 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Brol<en or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Laboratory Equipment AP

\ \\ , f ?7-\ Watch glass 1 Crucible and cover Evaporating dish Pneumatlo trough Beaker Safety goggles Florence Wide-mouth0 Plastic wash Dropper Funnel flask collecting bottle pipet Edenmeyer Rubber stoppers bottle flask € ....... ">. ÿ ,, Glass rod with niohrome wire Scoopula (for flame re,sting) CruoiNe tongs Rubber ubing '1 ,v .... Test-tube brush square Wire gau ÿ "\ file Burner " Tripod Florence flask: glass; common sizes are 125 mL, 250 mL, 500 .d Beaker: glass or plastic; common sizes are 50 mL, mL; maybe heated; used in making and for storing solutions. 100 mL, 250 mL, 400 mL; glass beakers maybe heated. oÿ Buret: glass; common sizes are 25 mL and 50 mL; used to Forceps: metal; used to hold or pick up small objects. Funnel: glass or plastic; common size holds 12.5-cm diameter measure volumes of solutions in titrafions. Ceramic square: used under hot apparatus or glassware. filter paper. Gas burner: constructed of metal; connected to a gas supply Clamps" the following types of clamps may be fastened to with rubber tubing; used to heat chemicals (dry or in solution) support apparatus: buret/test-tube clamp, clamp holder, double buret clamp, ring clamp, 3-pronged jaw clamp. in beakers, test tubes, and crucibles. Gas collecting tube: glass; marked in mL intervals; used to 3: Clay triangle: wire frame with porcelain supports; used to o} support a crucible. measure gas volumes. Glass rod with nichrome wire: used in flame tests. Condenser: glass; used in distillation procedures. Q. Crucible and cover: porcelain; used to heat small amounts of Graduated cylinder: glass or plastic; common sizes are 10 mL, 50 mL, 100 mL; used to measure approximate volumes; must solid substances at high temperatures. -

BUYERS GUIDE Standards Buyers Guide

Annex BUYERS GUIDE Standards Buyers Guide ASTM C 39 Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens ASTM C 29 Select load frame of appropriate load capacity GW-135 Portable Bench Beam Balance, 131 lb CM-200 300,000 lb capacity w/ single readout Or GW-34413 Electronic Bench Scale, 200 lb CM-216 300,000 lb capacity w/ advanced readout C-353 Tamping Rod, 5/8” dia CM-400 500.000 lb capacity w/ single readout G-29202 Scoop CM-416 500,000 lb capacity w/ advanced readout G-170 Thermometer, General Purpose The above come with platens for 6 x 12 cylinders. Select appropriate Platen sets if other size cylinders Choose unit weight bucket based on aggregate size are to be tested. C-601 Unit Weight Bucket, 1/10 cu ft C-18040 Cube Platen Set, 2” specimens C-603 Unit Weight Bucket, 1/3 cu ft C-18060 Platen set for 3x6 cylinders C-605 Unit Weight Bucket, ½ cu ft C-18070 Platen Set for 4 x 8 cylinders C-609 Unit Weight Bucket, 1 cu ft C-170 Flexural Beam Test Attachment Choose Strike Off Plate 301110 Splitting Tensile Strength Bar C-61130 Strike Off Plate, 10 x 10 in (Note: On site calibration of load frames required upon C-61150 Strike Off Plate, 12 x 12 in delivery and anytime load frame is moved.) C-61190 Strike Off Plate, 16 x 16 in, ½ in thick, acrylic ASTM C 40 AASHTO T 21 ASTM C 31 Organic Impurities in Fine Aggregates for Concrete Making & Curing Concrete Test Specimens in the Field C-404 Organic Impurities Test Set Choose appropriate size molds Consist of: C-209 Lipped Concrete Mold, 6 x 12 C-405 16 oz Graduated Glass Test Bottle (6) C-20910 -

Science Apparel, Balance & Scales

Science Apparel, Balance & Scales APPAREL / APRONS Mass Set Attachment Used to increase balance capacity to Rubberized Aprons 2610g, consists of 2-1,000g masses Light weight, charcoal colored, acid resistant and 1-500g mass. Qualifying Standard: cloth sheeting. Protects from chemical splashes Ohaus. with cotton ties at neck and waist. Reinforced stress points. Qualifying Standard: Quincy • For use with KCDA No. 02215 and Ohaus models 750SO, Specialties, Toplab. 710, 710T, 720, 760 and 730. KCDA No. U/M KCDA No. Size U/M 02200 ...................................................................................................3/Set 44028 .............. 24”Wx30”L - Childs .........................................................Ea 02150 .............. 27”Wx36”L - Adult ...........................................................Ea Scout Pro USB Interface Translucent Plastic Aprons This interface kit is a unique solution Resistant to laboratory reagents, acids, oils, to the problem of connecting a balance alkalies and grease, tapes at waist and neck, to a computer using a Universal Serial 6 ml thickness, reinforced at points of strain, Bus (USB). Data sent from the balance individually packaged. Qualifying Standard: to a computer is in USB format. The Quincy. USB data is directed to a virtual port. KCDA No. Size U/M This port then appears as an RS232 02157 .............. 27”Wx36”L - Adult ...........................................................Ea port to the application program. Ohaus, 44029 .............. 24”Wx30”L - Childs .........................................................Ea No Substitute. • Fits KCDA Nos. 02211, 02212, 02219 and 04540. APPAREL / COATS KCDA No. Mfg. No. U/M 02240 .............. 7114737 ..........................................................................Ea Lab Coats Ohaus Pan Cover White, twill woven blend of 65% Stainless steel weighing pan cover. Ohaus, No polyester and 35% cotton, 3 single Substitute. pockets and collar. 43” long, Qualifying • Fits KCDA Nos. -

Spectrophotometric Determination of Chloride Ion. Hans Coll Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1957 Spectrophotometric Determination of Chloride Ion. Hans Coll Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Coll, Hans, "Spectrophotometric Determination of Chloride Ion." (1957). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 197. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/197 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPECTROPHOTOMETRIC DETERMINATION OF CHLORIDE ION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Chemistry by Hans Coll M.S., Louisiana State University, 1955 June, 1957 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author wishes to express his sincere appreciation and gratitude to Dr. Philip W. West under whose direction this investigation was carried o u t . He is also indebted to Dr. R. V. Nauman and Dr. J. G. Traynham for their advice in the com pletion of this dissertation. He further wishes to acknowledge the financial support given by the Office of Ordnance Research. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS page I. ACKNOWLEDGMENT................................ii II. LIST OF T A B L E S ................................ iv III. LIST OF F I G U R E S . v IV. ABSTRACT ....................................... vi V. CHAPTER ONE: THE QUANTITATIVE DETERMINATION OF CHLORIDE .............. -

In Science We Must... Make Careful Observations!

In Science we must... Make careful observations! It's Practice Time! 1 Scientific Method Overview 2 The Seven Steps of the Scientific Method 1. State the Problem: What is it that you are trying to solve? This should be in the form of a question. 2. Gather Information: Research your question. Find out as much information as you can on your question. 3. Form a Hypothesis: Take a guess at the solution to the problem. 4. Run your Experiment: Test your hypothesis. Run an experiment to see if your hypothesis is correct. This should include step by step procedures for completing the experiment 5. Record and Analyze Data: Write down your results from your experiment in an organized fashion. 6. Draw Conclusion: Based on your results, was your hypothesis correct or incorrect. How do you know? What is your proof? 7. Repeat Your Work: Repeat your work to make sure you were correct. 3 Practice Time The Seven Steps of the Scientific Method Draw Conclusion Research your question. Find out as much information as you can on your question. State the Problem Write down your results from your experiment in an organized fashion. Repeat Your Work What is it that you are trying to solve? Record and Analyze Data This should be in the form of a question. Do the experiment over Gather Information Test your hypothesis. Run an experiment to see if your hypothesis is correct. This should include step by step procedures for Form a Hypothesis completing the experiment. Take a guess at the solution to the problem. -

Hf 135 Piping Loss Test

HB 201 HYDROSTATICS PANEL GENERAL DESCRIPTION: The equipment is a bench top unit for the study of basic properties of fluids in hydrostatic conditions. Components are placed on the panel. The unit can be placed on a suitable bench top and requires outside water supply to be stored in the provided storage tank. Instruction manual is also included. EXPERIMENT CAPABILITIES: . Measurement of level, pressure, temperature, specific gravity, viscosity, humidity. Demonstration of Pascal’s law, Archimedes principles, capillary effect. TECHNICAL DATA: The accessories for the panel include: . Inclined water manometer . Barometer . Hygrometer . Thermometer . Hydrometer . Stainless steel vernier hook gauge . Capillary attraction plates . Capillary tubes . Capillary viscometer . Falling sphere viscometer . Specific gravity bottle . Triple beam balance . Beaker, graduated cylinder and pipette. SP 111 Archimedes apparatus. SP 112 Pascal’s apparatus. Software for data display and analysis by computer (separately supplied). Storage tank OPTIONAL EQUIPMENT for demonstration and determination of additional properties. U-tube mercury manometer : 0-450 mm x 1 mm graduation with hand air pump and 0-1 kg/cm2 Bourdon gauge Note: Due to transport laws, mercury cannot be supplied. Buyer must source it locally. HB011 Dead weight pressure tester. HB012 Hydrostatic pressure. HB014 Metacentric height. SP 114 Surface tension apparatus. SP 113 Boyle’s law apparatus. HF 033C Portable differential pressure meter. Steel cabinet for panel support and accessories storage. Other optional equipment, please contact manufacturer ([email protected]) : 54 x 91 x 80 cm Net (unpacked) shipping dimensions WxLxH Net weight : Approx. 31 kg ESSOM CO., LTD. 508 Soi Taksin 22/1 Taksin Rd. Bukkalo Thonburi Bangkok 10600 Thailand W 040419 Tel. -

Copper's Chemical Properties

Copper’s Chemical Properties Topic Copper has unique properties that can be demonstrated in a series of chemical reactions. Introduction Copper is a reddish-orange transition metal that is an excellent conductor of energy. Copper metal, which occurs commonly in nature, is widely used in electrical wiring, construction, plumbing, sculpture, and as currency. As element 29 on the Periodic Table, copper tends to form cations in chemical reactions. During oxidation, copper generally loses electrons and acquires a charge of 2, but it can also oxidize to form stable 1 compounds as well. Because of copper’s reactivity with other substances, it can undergo a variety of chemical changes. For instance, copper metal dissolves in nitric acid to form a liquid. The liquid can react with sodium hydroxide to yield copper (II) hydroxide. When the copper (II) hydroxide is heated, it forms copper (II) oxide, which can be dissolved in acid. Copper (II) ions can then be reduced with zinc metal to produce copper metal. In this experiment, you will perform a series of five reactions involving copper. At the conclusion of the reactions, you should end up with a yield of copper metal very similar to the mass of copper with which you started. Time Required 40 minutes Materials ✒ 250-milliliter (ml) beaker ✒ waste beaker © Infobase Publishing COPPER’S CHEMICAL PROPERTIES 2 ✒ stirring rod ✒ copper wire ✒ wire cutters ✒ 4 ml of concentrated (16M) HNO3 ✒ 20 ml of 3M NaOH ✒ 15 ml of 6M H2SO4 ✒ zinc metal (about 3 grams [g]) ✒ 20 ml of 6M HCl ✒ deionized water (about 200 ml) ✒ graduated cylinder ✒ electronic scale or triple-beam balance ✒ steel wool ✒ wire cutters ✒ hot plate ✒ rubber policeman ✒ watch glass ✒ pH paper ✒ science notebook Safety Note Take care when working with Bunsen burners, open flames, and chemicals. -

Download Catalog

HB 200 HYDROSTATICS BENCH GENERAL DESCRIPTION: The equipment is a self-contained unit for the study of basic properties of fluids in hydrostatic conditions. Water is provided in a storage tank of the bench with a pump to deliver water for the experiments. Accessories for individual experiments are placed on the bench panel and can also be stored in the bench cabinet. The unit is on steel frame on wheels. Instruction manual is also included. EXPERIMENT CAPABILITIES: . Measurement of level, pressure, temperature, specific gravity, viscosity, humidity. Demonstration of Pascal’s law, Archimedes principles, capillary effect, . hydrostatic pressure. Determination of metacentric height. Calibration of pressure gauge. TECHNICAL DATA: The accessories for a bench include: . Inclined water manometer . Barometer . Hygrometer . Thermometer . Hydrometer . Stainless steel vernier hook gauge . HB011 Dead weight pressure tester . HB012 Hydrostatic pressure . HB014 Metacentric height . Capillary attraction plates . Capillary tubes . Capillary viscometer . Falling sphere viscometer . Specific gravity bottle . Triple beam balance . Beaker 1000 ml, graduated, cylinder 1000 ml, and hand pipette. SP111 Archimedes apparatus . SP112 Pascal’s apparatus . Storage tank with pump . Bowl . Software for data display and analysis by computer (separately supplied). Power supply : 220 V, 1Ph, 50 Hz. Other power supply is available on request. OPTIONAL EQUIPMENT: . U-tube mercury manometer : 0-450 mm x 1 mm graduation with hand air pump and 0-1 kg/cm2 Bourdon gauge Note: Due to transport laws, mercury cannot be supplied. Buyer must source it locally. SP 114 Surface tension apparatus . SP 113 Boyle’s law apparatus . HF033C Portable differential pressure meter . Other optional equipment, please contact manufacturer ([email protected]) Net (unpacked) shipping dimensions WxLxH : 73 x 91 x 169 cm Net weight : Approx.